Small Details You May Have Missed In 25th Hour

Released in 2002, Spike Lee's "25th Hour" was very much one of the earliest narrative depictions of a post-September 11th New York City. While the source material, a novel of the same name, was published four months before the terrorist attacks, author/first-time screenwriter David Benioff adapted his own work to capture a city still struggling to process the scarring event. Both New Yorkers born and raised, Lee and Benioff matched well in presenting a wounded place that refused to succumb to hopelessness or lose its hometown pride.

Ostensibly telling the story of convicted drug dealer Monty Brogan (Edward Norton) and his last day of freedom, this backdrop gave the story a deeper resonance. In addition to seeing New York City processing its grief, viewers witness Monty and his friends and family process a smaller, personal upheaval.

With these heavy themes paired alongside Lee's gift for visual flair and plot dynamics, it's no wonder "25th Hour" rewards repeat viewings. Here are some themes and references that viewers may have missed the first time.

The wounded dog represents an angry, frightened America

Introduced in flashback in a seemingly abandoned and rubble-strewn section of the city, a dog lies alone, deeply wounded. Monty and his lieutenant Kostya Novotny (Tony Siragusa) initially incorrectly assume the canine is at death's door and plan to end his suffering. However, as Monty approaches, the dog begins to snap and growl. Even in his critical state, he manages to cut Monty. Impressed with the fight still in the animal, Monty elects to bring him to a vet. Christened "Doyle," the dog becomes the protagonist's constant companion, one of the few aspects of his life Monty makes sure to specifically request someone else take responsibility for after he goes away.

Given the film's setting — and a credits sequence that focuses entirely on the newly World Trade Center-devoid New York City skyline — the metaphor is clear. Doyle is New York. Injured, mad, confused, perhaps lashing out in all the wrong ways. But also resilient, strong, and a survivor even when all the odds would suggest that being nearly impossible. So before viewers even know "25th Hour" is about New York City's recovery, Lee is already laying the groundwork.

An addict's struggle

In the first present-day scene of "Hour," Monty attempts to begin his morning via some quiet time with his dog at Carl Schurz Park overlooking the East River. Instead, Simon (Paul Diomede) approaches the protagonist and his pet. A customer and addict, Simon begs Monty to sell to him. While Monty couldn't even if he wanted to — after all, the dealer has been "touched" and is a day away from his jail sentence — he nonetheless treats Simon with kneejerk cruelty. It's difficult to watch in light of Simon's obvious struggling state.

However, it isn't until an hour later that the true impact of Simon's appearance sinks in. In a flashback that focuses on how Monty met his girlfriend Naturelle (Rosario Dawson), the first significant interaction viewers witness has nothing to do with the future couple. Pacing outside a playground, a well-dressed, calm, and collected Simon approaches Monty, seeking to score. While he is more than happy to sell at this time in his life, Monty maintains a coldness toward his customer. When Simon attempts to connect his dealer with someone else, Monty becomes agitated and dismissive, literally burning the information moments after Simon walks away.

The dual scenes demonstrate the true cost of Monty's business to those who funded his lifestyle, of course. However, it also reveals Monty's attitude towards those customers, rooted in disdain.

Isiah Whitlock Jr.'s The Wire reference

With a career dating back to 1981 and over 100 roles to his name, Isiah Whitlock Jr. has turned in plenty of performances worthy of praise. Beginning with his appearance in "25th Hour," he became a member of Spike Lee's ensemble, appearing in 8 Lee projects in the past 20 years, including memorable turns in "Da 5 Bloods" and "Chi-Raq."

Of course, his most renowned work is "The Wire," where he played the morally-flexible State Senator Clay Davis. Charismatic and seemingly untouchable, Davis repeatedly enriched himself, conning criminals, public officials, and voters with a certain glee. Even when he finally faced trial, Davis was convinced he had just the right thing to say to escape further consequences.

It was a breakthrough turn for sure, capped off by an especially enduring catchphrase, arguably the most famous on a very quotable show.

Although "The Wire" and "25th Hour" both came out within months of each other, it seems like Whitlock had already been warming up his vocal cords for multiple seasons of dragging out the four-letter colloquialism for feces — always with an impressive extending of the first syllable. Within moments of his appearance on screen in "Hour," Whitlock drops the word that is to him what a certain four syllable phrase is to Samuel L. Jackson. Looking back now, any "Wire" fan can't help but smile. Undoubtedly, Whitlock is also smiling, as he is very aware of his catchphrase legacy and, while surprised, doesn't mind it one bit.

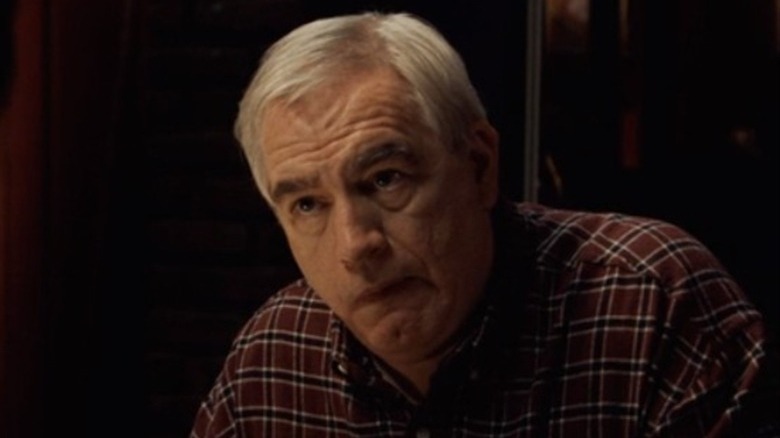

Monty Brogan's father is in recovery

Monty's father James (Brian Cox), a former firefighter turned bar owner, sees his establishment as a living memorial to his former career and the fallen NYFD heroes of September 11th. A kind man, he doesn't hide his vulnerability or sadness. He openly mourns his wife, Monty's mother, and seems in the process of doing the same for his soon-to-be-imprisoned son.

While only confirmed late in the film, Cox's performance also reflects that James is a man in recovery. As he opens bottles and taps kegs, he conspicuously is never without a glass of water filled with ice and one lemon slice.

A somewhat facile reading may point to how both father and son deal in addictive substances. However, the stronger and more interesting point of comparison is to Monty's customer Simon. While James' sobriety could've acted as a cudgel against the still-using Simon, the script and Lee both use it to illustrate how difficult addiction can be for everyone, even the sober. When James fantasizes about helping his son escape prison, he mentions them sharing a final drink. Both the reverence with which Cox speaks of the barley and how he drinks hint at the power of addiction, even for those fortunate enough to have attained sobriety. James' story gives Simon something Monty refuses to have: recognition of the addict's humanity.

Edward Norton and Brian Cox's Red Dragon connection

While "25th Hour" is the first and only time Edward Norton and Brian Cox have shared the screen, the two have another connection that preceded their collaboration here. Both Cox and Norton were featured in adaptations of the Thomas Harris novel "Red Dragon."

Cox did it first, becoming the original actor to play Hannibal Lecktor (yes, with that alternate spelling) on the big screen in the 1986 Michael Mann adaptation of the book "Manhunter." While Anthony Hopkins' is by far the more well-known interpretation, critics also praised Cox's work. As Collider recently pointed out, Cox's serial killer was far less suave and seductive and far more self-involved than Hopkins' cosmopolitan Lecter. The result is a more authentically sociopathic, and down-to-earth, interpretation of the cannibalistic psychiatrist.

Months before the release of "25th Hour," "Red Dragon" was adapted a second time, this one from Brett Ratner and acting as a de facto "Silence of the Lambs" sequel. In it, Norton portrays FBI profiler Will Graham, the agent who eventually brings the film's main villain — the murderous Tooth Fairy (Ralph Fiennes) — to justice. Unfortunately, to do so, he needs to tangle with Lecter (Hopkins), the man who nearly killed Graham only a short time before.

It certainly lends the duo's deeply felt father-son dynamic a different spin to imagine Norton and Cox reprising their roles as the gifted but haunted profiler and the dangerous sociopathic murderer.

An encore, of sorts

Almost certainly, the most famous single scene in "25th Hour" features Norton's Monty facing off against a version of himself in a bathroom mirror. In a self-pitying monologue dressed up as a macho tirade full of racial, ethnic, and homophobic epithets, Monty's mirror self runs down the entire city, essentially blaming it for his downfall. As the diatribe reaches its climax, he responds, admonishing himself for throwing away all his opportunities and being the only one to blame for his choices and upcoming incarceration.

The scene is intense, tragic, and, ultimately, deeply vulnerable. It also echoes a scene from Spike Lee's 1989 masterpiece "Do The Right Thing." While not driven by a single character, that scene is a similarly tightly edited montage of New York City residents, including characters played by John Turturro and Lee himself, spewing racial and ethnic slurs against one another.

While similar in tone and execution, the scenes serve different functions. In "25th Hour," the mirror scene's purpose is to show how heavily-armored Monty is against acknowledging his role in his own downfall, and how even that armor can't hold. In "Do The Right Thing," it reveals the racial tension that exists in a Brooklyn neighborhood, foreshadowing the riot that is to come.

Interestingly, despite the scenes feeling so similar, Monty's monologue is not wholly a creation of Lee's. The words and location of the outburst come almost directly from Benioff's book.

Edward Norton quotes himself from American History X

The famous mirror scene isn't only a thematic and visual quotation of "Do The Right Thing"; it is a quotation of one of Edward Norton's earlier works as well.

At one point, Norton's Monty turns his ire on the Black men he reductively characterizes as playing basketball uptown and blaming white men for all their problems. He specifically notes the span of time since slavery was officially outlawed in the United States. Intentionally or not, this line is quite similar to one spoken by Norton's skinhead white supremacist, pre-reformation, in the film "American History X."

Here, as with the connection between "25th Hour" and "Do the Right Thing," the purpose of the line is very different. In "American History X," it is being spoken by a then truly avowed racist as an expression of his hatred. There are no layers, no depth. The character, Derek, is filled with hate and spewing it to harm others.

Monty, by contrast, is falling apart. His performance is done entirely in the mirror because it is all self-directed. The epithets he spits are his last-ditch effort to deny responsibility for ruining his own life. While no less inappropriate, bracing, and discomforting, the scene's resolution makes it clear that although he tried desperately to pin his downfall on anyone else, he ultimately had to admit it all came back to his choices.

Ground Zero's power

As part of his final day of freedom, Monty plans to meet up with childhood friends for a going away party. While waiting to meet Monty, high school teacher Jacob (Philip Seymour Hoffman) and Wall Street trader Frank (Barry Pepper) kill time together. Among their activities is Frank showing off his apartment. From Frank's window, one can see people and machinery moving the rubble, attempting to clear away the physical evidence at Ground Zero. It looks like a construction site, yet history makes it breathtaking — in the most frightening way.

This is another moment of parallel that Lee draws between the City and Monty. Scores of New Yorkers go to jail or prison every day. Monty only stands out because his friends and family — and the audience, by extension — know him. Therefore, his incarceration matters.

Similarly, knowing the tragedy that took place at Ground Zero gives the site an undeniable power. Hoffman and Pepper's body language illustrate how that power affects New Yorkers — and Americans in general. Pepper's Frank cannot stop staring, can't look away. Hoffman's Jacob, by contrast, can only handle fleeting glances. His eyes are constantly scanning. They drift over and away or linger on some corner of the window, ensuring the site remains out of focus for him. Some Americans were too traumatized to stop thinking about 9/11; others simply couldn't process it.

Class resentment

Class resentment and jealousy mar Monty and Frank's relationship, despite being longtime friends. At different times in the movie, both reference the other's occupation — drug dealer and stock broker, respectively — in disdainful terms. Additionally, Monty seems aware of Frank's opinion of him, noting that he can feel his best friend judging him, even while Frank not so subtly ogles Naturelle. As two scholarship kids who attended a private school together, you'd expect they might be happy for the other's success, wealth, and status, but that's clearly not the case.

Intriguingly, Jacob seems to neither be resentful nor judged by either for his socioeconomic status. While his job, high school teacher, likely pays significantly less than either of his friends, he also comes from money. He, in essence, can afford to live in New York and work for less money because of generational wealth. Yet, neither Monty nor Frank resents his privileged status — or his freedom to avoid the legally/ morally dubious careers they've pursued to catch up.

Who gets champagne?

After finally reaching the club where he'll spend the majority of his last night as a free man, Monty orders a bottle of champagne. When everyone — Jacob, Naturelle, Frank, Monty himself, and Jacob's student Mary (Anna Paquin) has a glass, Monty offers a brief, but nonetheless biting toast: "Champagne for my real friends, and real pain for my sham friends."

This Francis Bacon quote is either a conscious or subconscious dig on Monty's part. Earlier in the film, it's suggested someone ratted out Monty. Given that three of the people he's closest to in the world — Naturelle, Frank, and Jacob — are sitting there with glass in hand, the proverbial sham friend — or friends — are very likely present.

While the Bacon quote inspired Monty's toast, Monty's toast, in turn, inspired the band Fall Out Boy. On their breakthrough album "From Under the Cork Tree," they have a song that bears the unwieldy title, bemoaning friends who only like them while "they move units," a reference to albums in this case, not bricks of heroin as with Monty. Fall Out Boy have similarly referenced the films "Dirty Dancing," "Casablanca," "Shawshank Redemption," and more with other song titles (in addition, of course, to getting their band name from "The Simpsons").

The circular inspiration didn't stop there, however. "One Tree Hill," a show that FOB bassist Pete Wentz appeared on multiple times as himself, titled the third episode of Season 3 episode "Champagne for My Real Friends, Real Pain for My Sham Friends," after the Fall Out Boy tune.

Exploiting the customer

Monty, of course, has the most exploitative job among his friends. A drug dealer, his livelihood depends on people buying physically and psychologically addictive substances from him. He is aware of the cost of addiction, yet does it nonetheless.

Frank's work as a stock broker is only slightly less evident in its exploitation of customers. In 2002 (and now), many Americans had a distrust and distaste for those in the financial sector, thanks to events like the Enron scandal. Additionally, when viewers see Frank at work, he ignores advice and orders from his boss, holding onto stocks with the expectation that the unemployment numbers announcement will benefit him, his company, and his clients. It pays off in the end, but it is a considerable risk that makes it clear Frank doesn't spend much time worrying how his choices might hurt the people who trust him to help them invest their money wisely.

Jacob, initially, seems the outlier. He's a school teacher who appears to be dedicated to his job. Then his brightest student Mary, a 17-year-old with poor parental supervision, rides Monty's coattails into the club. Outside the school structure and intoxicated, Jacob follows Mary to an isolated bathroom and kisses her. While the situation doesn't go any further — and Jacob seems to grasp the violation immediately — he nonetheless crossed a line.

Spike Lee's signature glide

While Spike Lee has several style and thematic fingerprints, perhaps none of them are as arresting as his double dolly shot. Frequently employed to convey a character unmoored or out of control by events, the effect places the subject in frame and stays with them as they race away from or towards a problem. Because the effect makes it seem like the person is moving without moving, it gives a scene an ominous feeling that conveys the character's sense of loss of control.

In "25th Hour," it happens three times.

The first of these is brief. After Monty enters the nightclub for his final few hours of fun, the camera settles on the back of Norton's head. He and the camera glide into the action of the VIP area, then the camera rises above Norton to reveal the larger scene.

Next is a dolly shot of Anna Paquin's character, headed into the VIP area, high on ecstasy. Shot from above the top of her low-cut outfit, she looks naked as she undulates in bliss.

Some ten minutes later, we see the true and full effect with Hoffman. After kissing Mary in the bathroom, Jacob leaves and is captured by the double dolly while descending the stairs. Shot from an angle slightly above Hoffman, the camera tilts downward as he looks up into it, his face awash with confusion and anguish about how he could've done that to a student.

Lee's use of the double dolly in this film — particularly in a nightclub context — is reminiscent of Martin Scorsese, who famously employed the technique to similar effect in "Mean Streets." Lee and Scorsese are longtime friends and mutual admirers.

Quiet confessional

"25th Hour" uses space and sounds in interesting ways. In particular, throughout the film, characters are captured at their most honest when the scene is largely devoid of sound or interruption. Monty must retreat to the bathroom at his father's bar to confront himself. Frank and Jacob need to be in Frank's "incredibly quiet for a New York City apartment" home to be honest with their feelings about Monty going away. Monty's father, James, can only offer to help Monty escape when they are both together alone on the road in James' car.

The most noticeable of these moments is the blue gel-saturated lounge above the dance club. While the downstairs VIP room is buffered some from the music and, as a result, allows Monty to fire off his passive-aggressive toast about fake friends, the lounge above is utterly silent. Only then can Monty reveal his true feelings to Frank. This room is the only time, up until that moment, that Monty has been honest about how he feels in regards to going to prison. The quiet isolation once again provides a character with a catalyst to expose themselves honestly and vulnerably.

Stopping the freefall

In addition to a goodbye to life outside prison, Monty's final day provides him with several tests that only in retrospect do we realize he must pass to move beyond his mistakes. The first of these is to stop dealing drugs. While the DEA's raid effectively does that, Monty's refusal to sell to Simon at the film's beginning affirms that Monty has not returned to the hustle.

The second test comes when Uncle Nikolai (Levani) reveals to Monty that it was Kostya who betrayed him to the police. After spending most of the film fuming about Naturelle being the likely informant, the reveal of Kostya as the true betrayer seems to free Monty from his resentment and desire for revenge.

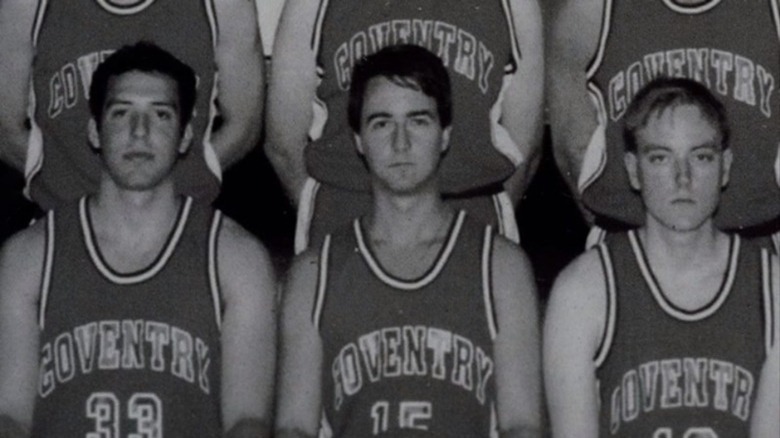

Finally, Monty needs to stop fighting. When the dealer visits Jacob at their former school early in the film, he shows off an old basketball team photo in the high school's trophy case. As he regales the administrator with tales of his skill, she asks the obvious question: What happened after that picture? Monty is then forced to admit he was kicked off the team for fighting.

In this way, the fighting, not the dealing, is Monty's original sin. But, by goading Frank into beating him and refusing to fight back, Monty vividly demonstrates he is finally rejecting that sin as well. He is not giving up; he's just letting go of fighting purely for fighting's sake.

Two versions of America

Norton spits a dark, pessimistic interpretation of America at the mirror about one-third of the way into the film. The angry, hateful monologue presents a vision of New York City — and the US by implication — lost to tribal strife, unable to ever live up to the name United States. Ethnic, religious, racial, sexual, and even occupational divides have simply pushed us all too far apart.

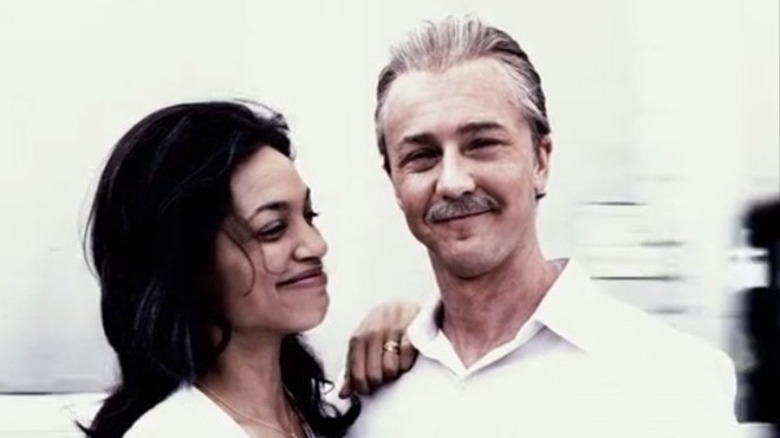

In the film's closing moments, Cox offers a rebuttal. Describing an America of second chances, where strangers provide a helping hand, James tries to tempt his son into running from incarceration. Laying out the promise of going West, but for modern times, he describes a country where people will recognize and respect a man trying to do better and not judge him for his past.

By nature of Monty and Naturelle's ethnic and racial differences, it also visually mixes in an old-fashioned, melting pot vision of America. Seated among his multi-generational family, mixed-race children and grandchildren lovingly surround Norton.

It is, perhaps, a bit Pollyanna-ish, but that's the point. Monty told himself a story about the absolute worst version of the United States in his father's bar. In response, his dad tries to assert the possibility of America at its very best. A place of redemption where anyone has a chance. A place where we are all part of the American experiment and equally worthy of laying claim to it, no matter our demographic identifications.