The Untold Truth Of Princess Mononoke

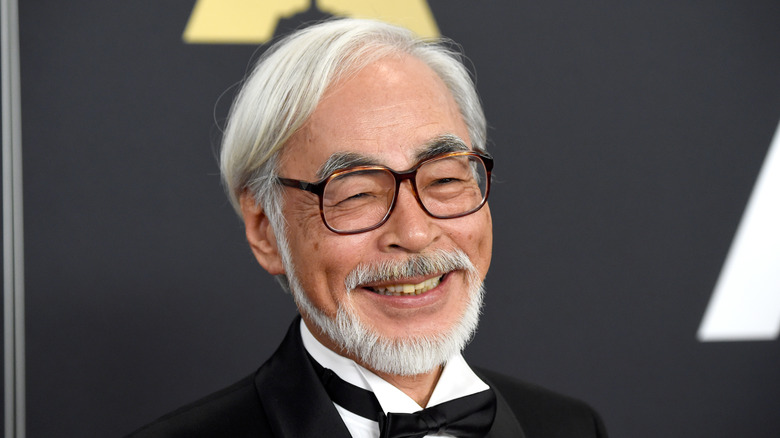

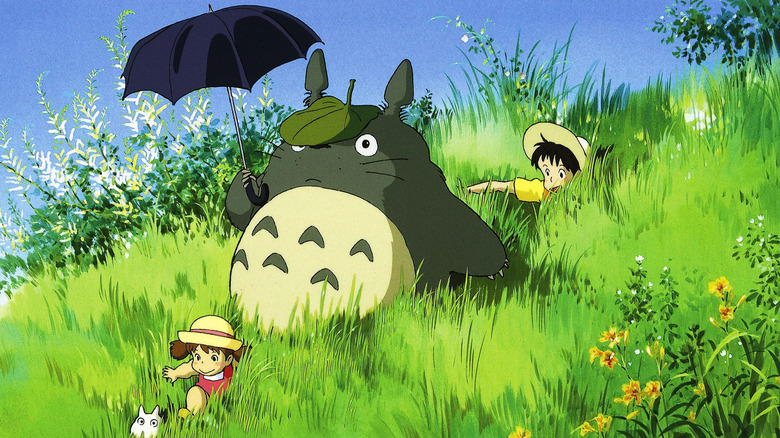

There are happy-go-lucky children's movies, and then there's "Princess Mononoke" — the two are not the same. Prior to the release of what some consider his magnum opus, famed animator Hayao Miyazaki was primarily known for sweet, albeit emotionally complex, children's films like "Kiki's Delivery Service" and "My Neighbor Totoro." With 1997's "Princess Mononoke," he took a darker turn, honing in on the horrors of war and environmental destruction.

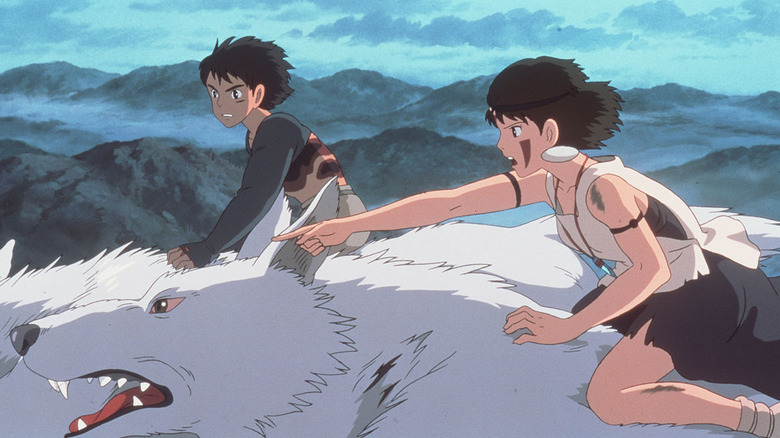

Though it may not exactly be suitable for all ages, Miyazaki has consistently maintained that "Princess Mononoke" is a film that children (at least of a certain age) should see, as the lessons it imparts are extremely important, especially for those who still have hope about the future. If you've seen the film, you probably understand why some parents might be hesitant to show it to their kids. It's surprisingly violent, especially in the first few minutes, and the story is far from rainbows and sunshine.

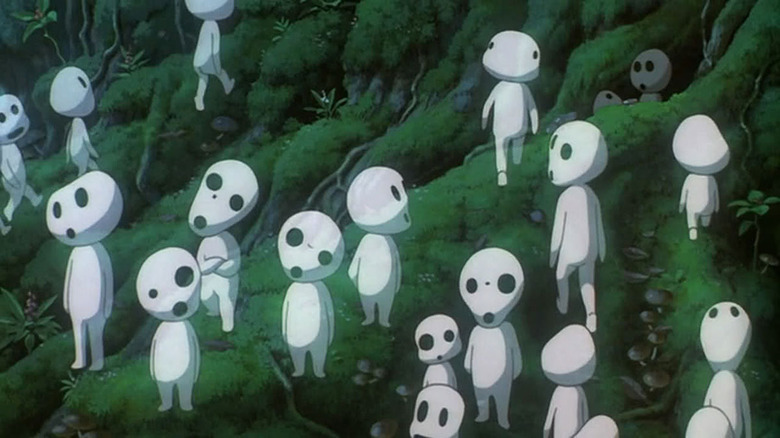

But as viewers have to expect from Miyazaki's films, there are plenty of fantastical (and adorable) creatures that populate the world, including enormous wolves and the cutest little spirits you've ever seen. It's arguably Miyazaki's most complex film, a ton of work went into making the film, and there's plenty to learn once you pull the curtain back. Curious? Keep reading to discover the untold truth of "Princess Mononoke."

Neil Gaiman wrote the English translation of Princess Mononoke

One of the most oft-repeated legends surrounding "Princess Mononoke" concerns the authorship of the English translation. It had long been rumored that famed British author Neil Gaiman wrote the English translation of the script, but his name doesn't appear on the credits so no one was really sure. Finally, in 2019, Gaiman took to Twitter to confirm that this was true. He said the reason he doesn't appear in the credits is because Studio Ghibli asked that some of the Miramax executives be removed from the credits, and they decided to remove his name instead of removing their own.

Interestingly enough, Miramax had originally asked Quentin Tarantino to write the script, and Tarantino recommended Gaiman after turning the job down, reports SyFy. Gaiman's job would turn out to be more difficult than one might imagine, as he had to deal with demands from several sides. First, there were Miyazaki's demands for the script, then Miramax executives, and lastly the specific demands of Miramax of notorious head Harvey Weinstein.

As film producer Steve Alpert wrote in Polygon, the people at Miramax thought American audiences wouldn't accept certain aspects of the film without significant changes. For example, one Miramax executive thought audiences wouldn't believe Prince Ashitaka is a prince because he doesn't have a palace or nice clothes. But Gaiman stuck to his guns and wound up producing what's often considered one of the best translations of Miyazaki's work.

Miyazaki's strict rules about the script's translation

Though Hayao Miyazaki has been partnering with American studios like Disney (and Miramax, which was a subsidiary of Disney for a time) for many years now, the relationship hasn't always gone smoothly. For understandable reasons, Miyazaki has often found himself butting heads with studio executives who want to change his films significantly to satisfy the American market. In order to maintain the integrity of "Princess Mononoke" as it went through the translation process, Miyazaki came up with a list of demands that he thought needed to be included (or excluded) from the English script.

According to producer Steve Alpert (via Polygon), Miyazaki's suggestions were often about very specific ideas, but he also dispensed advice about casting. Alpert said some of Miyazaki's comments were things like "no contemporary language or modern slang" and "choose good voices; the voices are important." He also wanted to make sure those involved in producing the dub were aware of the cultural class distinctions present in the film, such as the fact that Ashitaka is a prince and thus behaves in an old-fashioned manner and that the people of Irontown are very low-class while Lady Eboshi herself is not. Miyazaki was also adamant that the weapons used in the film never be called rifles, as they're more like "portable canons."

Harvey Weinstein and the katana

There's a famous urban legend surrounding the production of "Princess Mononoke," and it happens to be (mostly) true.

It's long been rumored that Hayao Miyazaki sent a sword to Harvey Weinstein as a threat while the American dub was in production. The truth is that while Miyazaki himself didn't send Weinstein a threatening message, his producer did, the filmmaker explained to The Guardian in 2005. As the story goes, Weinstein was sent a katana in the mail, and attached to the sword were two simple words: "No cuts." (Weinstein was known in the industry as "Harvey Scissorhands" because of how much he would cut from films.)

While Miyazaki may not have sent the threat himself, he did meet with the now-disgraced Weinstein and hear his demands. "I did go to New York to meet this man, this Harvey Weinstein, and I was bombarded with this aggressive attack, all these demands for cuts," he said. "I defeated him." Though we wouldn't recommend sending swords through the post office, it's certainly an effective way to defeat your enemies.

One of the scenes took nearly two years to draw

"Princess Mononoke" is an incredible feat in animation, and considering its lengthy runtime, it's no surprise the film took years to complete. According to Miramax, only about 10% of the film is computer animated, which means the rest was drawn by hand. All in all, over 144,000 cels (transparent paper on which animation is drawn) were created for the film.

One of the most impressive scenes from an animation standpoint comes near the beginning of the movie. Ashitaka encounters a wild boar that's become infected by a curse known as the Tatarigami. The Tatarigami is a terrifying being who looks to be made up of hundreds of snake-like creatures and completely consumes the wild boar. One fan of the movie took to Twitter to ask Studio Ghibli about the scene, writing (via Sora News 24), "This has to be CG, right?"

It's a fair assumption, but it's totally wrong. Studio Ghibli responded to the tweet, explaining, "The part where the snakes move sluggishly was so difficult that — even though the scene is only a couple of minutes long — it took one year and seven months to finish!" They noted that it apparently took 5,300 drawings to complete, and one of the Ghibli artists said it got more and more confusing to draw as it went on. We'll definitely be thinking about all that work the next time we watch the scene.

Hayao Miyazaki was inspired by Westerns

"Princess Mononoke" contains many diverse characters and thematic elements, so it's only fitting that Hayao Miyazaki took inspiration from numerous sources. According to Miramax's official "Princess Mononoke" site, Miyazaki is a huge fan of the American director John Ford, who was primarily known for making Westerns. Many of John Ford's films — such as "My Darling Clementine" — take place in frontier towns, something Miyazaki paid homage to with the creation of Irontown (or Tatara Ba), a settlement that could easily be discussed in these terms.

Irontown is filled with outcasts and outlaws –- much like in a Western –- who have the strength to survive the tough environment of the frontier. Of course, "Princess Mononoke" also points out that this strength and ambitious mastery over one's domain spells disaster and destruction for the environment, which is exactly what Lady Eboshi's hunt for the forest spirit represents.

Contemporary conflicts convinced Miyazaki to make his darkest film

Compared to previous movies like "Kiki's Delivery Service" and "My Neighbor Totoro," "Princess Mononoke" is a strikingly dark and serious film. Speaking with Empire, Hayao Miyazaki described how risky the project was, especially considering his prior films. He explained that while working on "Porco Rosso," he learned of the war in former Yugoslavia and was disappointed that humanity kept repeating the same mistakes. "After that, we couldn't go back and make some film like 'Kiki's Delivery Service,'" he explained. "It felt like children were being born to this world without being blessed. How could we pretend to them that we're happy?"

He admits that he exhausted the animation team with the making of "Mononoke," which he expected would happen. But even once the film was completed, he wasn't sure about the final product. He didn't understand the movie himself, and he wasn't sure about who the audience was. "At first I decided, 'This is something children shouldn't see,' but in the end I realized, 'No, this is something that children must see,' because adults, they didn't get it — children understood it." Once he realized the importance of the film he made and how children would actually understand it best, he felt inspired to keep making films again.

The film's title was only partially translated into English

For English-speaking viewers of "Princess Mononoke," the title can be a bit confusing. There isn't actually a character in the film named Princess Mononoke, nor is the phrase ever actually uttered. The character who represents Princess Mononoke is actually San, the daughter of wolves and the protector of the forest, though she's never referred to by that name.

The reason for the confusion is because the film's title was only partially translated into English. The Japanese title for the film is "Mononoke-hime," with "hime" meaning "princess." "Mononoke" is a word that's difficult to translate into English, which is why it was kept untranslated in the title. However, it roughly translates to "vengeful or angry spirit," which means the title essentially means "Princess of the Angry Spirits." San's name actually means "three" in Japanese, and it's implied she is named this because she is the third child of her wolf god parent, Moro.

The English dub features an all-star cast

In his list of requirements for the English dub of the film, Hayao Miyazaki implored the executives at Miramax to "choose good voices." Luckily, in this arena they heeded Miyazaki's advice, as the English-speaking voice cast for the film is filled with sultry-voiced superstars. Billy Crudup voices Ashitaka, Claire Danes voices San, Minnie Driver voices Lady Eboshi, Billy Bob Thornton voices Jiko-bô, and Gillian Anderson voices Moro.

Anderson was an especially big get for the film, as she was at the height of her "X-Files" fame when the English dub premiered in 1999. At the film's premiere, Anderson was asked by Hollywood.com about her familiarity with Miyazaki's films prior to starring in "Princess Mononoke," and she explained that she'd been a fan of his movies for years. Anderson said of his work, "His films are very spiritual and very beautiful and very reverent," and she praised the way all of his films have a lesson to teach you. As for whether she would show the film to her children, Anderson wasn't sure at the time, noting that "Princess Mononoke" was much more intense than his previous movies.

The inspiration for the boar monster

One of the most shocking moments in "Princess Mononoke" is an early scene where a wild boar is taken over by a curse known as the Tatarigami. This turns the boar into a violent monster that Ashitaka must defeat, a heroic act that curses him in the process. In an interview with Roger Ebert, Hayao Miyazaki described how the scene with the boar monster was meant to represent the universal human emotion of rage. "I'm a very emotional person, and when I get enraged or furious, I feel like black insects crawl out of my pores," he explained. "My staff are more peaceful, so it was difficult for them to imagine what it feels like to be taken over by uncontrollable rage."

When Ebert asked if the boar was based on his own personal rage, Miyazaki conceded that it may be, but he also explained that he thinks rage and violence are deep-rooted impulses that all human beings possess. "The issue we confront as human beings is how to control and manage that impulse," he said. Though some might want to shield children from these impulses, Miyazaki maintained that it's important that they face this reality, as it's a part of all our lives.

Lady Eboshi has a fascinating backstory

Lady Eboshi may be the most interesting character in "Princess Mononoke," as she's a very complicated woman who's neither all good nor all bad. She's employed a group of former sex workers and given them important roles in the functioning of Irontown, and she provides a space for lepers who would be unwanted elsewhere. At the same time, she's intent on furthering industrialization at the expense of the environment, and she has no qualms about killing the holy forest spirit.

In a Twitter Q&A with fans, Studio Ghibli answered a question about the character's backstory. According to Sora News 24, the folks at Ghibli revealed, "Miyazaki has said that Eboshi was sold as a slave and became the wife of the leader of a band of Japanese pirates." But her story doesn't end there. "After she became a skilled fighter, she killed him, stole his treasure, and returned to mainland Japan."

This backstory explains how Lady Eboshi came to be the confident, competent woman that she is and why she has such a fondness for the former sex workers employed in Irontown. Several commenters on Twitter noted what an interesting character Lady Eboshi is, with one fan noting, "She's exactly like a modern person. She knows exactly what she has to do to achieve her goals and has no qualms about taking those actions."

There might be a connection between Princess Mononoke and My Neighbor Totoro

Studio Ghibli fans are often keen to draw connections between Hayao Miyazaki's many films, and there's been a persistent rumor that one such connection exists between "Princess Mononoke" and his 1988 movie "My Neighbor Totoro." As the story goes, the last remaining tree spirit at the end of "Princess Mononoke" goes on to become one of the Totoros in the '88 film. (Though "Totoro" came out before "Mononoke," it takes place several hundred years later.)

One fan asked Studio Ghibli whether or not this rumor is true on Twitter, and the studio answered. "During production, it seems that Miyazaki said something along those lines to the staff," was their response (as translated by Sora News 24). While it may not be a categorical "yes," it does seem like there's a good chance that Miyazaki did make the connection between the two films himself at one point. Either way, it's fun to think about all of Miyazaki's movies existing in the same universe or on the same timeline, much like the theory of the Pixar timeline.

Every piece of sound design had its own logic

While fans of "Princess Mononoke" might spend much of their viewing time marveling at the film's magnificent animation, there are other elements of the film that deserve our attention too. Sound design is an important part of all filmmaking, and Studio Ghibli revealed a few fascinating tidbits about this component of the film during their Twitter Q&A. They revealed that the distinctive noise the tree spirits make was created using wooden castanets because producers thought the spirits should have a wood-like quality about them due to their connection with nature.

Producer Toshio Suzuki revealed that one sound design element he's proud of can be found during the fight between San and Lady Eboshi. According to Suzuki, they spent a lot of time making sure Lady Eboshi's metal sword had a distinct sound that was different from San's dagger, which was made from bone. We probably wouldn't have noticed this distinction on our own, but now that we know, we're going to have to keep an ear out during our next viewing.

Miyazaki has hope for the future of the characters

In many reviews of the film, critics have praised "Princess Mononoke" for the way it eschews easy divisions between good and evil and doesn't include an overly simplistic happy ending. In reference to the film's somewhat ambiguous conclusion, an American journalist asked Hayao Miyazaki if he thought of San and Ashitaka as a tragic couple because they can't be together. In response, Miyazaki said, "They remain involved. I'm sure that they maintain a good relationship." So they aren't really the tragic duo some perceive them to be.

Nonetheless, Miyazaki imagined that the future will not be easy for either of them. He explained that Ashitaka will help San stay alive, but that he will also dedicate himself to helping the people of Iron Town, and therein lies the difficulty. "And this will tear Ashitaka apart," Miyazaki described. "But this won't stop him. Because he treasures both." He went on to say that this difficulty is exactly the kind of lesson that contemporary viewers can take from the story. It may not be a sappy happy ending, but according to the creator himself, life does go on.