Our Simpsons Expert Answers The World's Most Difficult Simpsons Questions

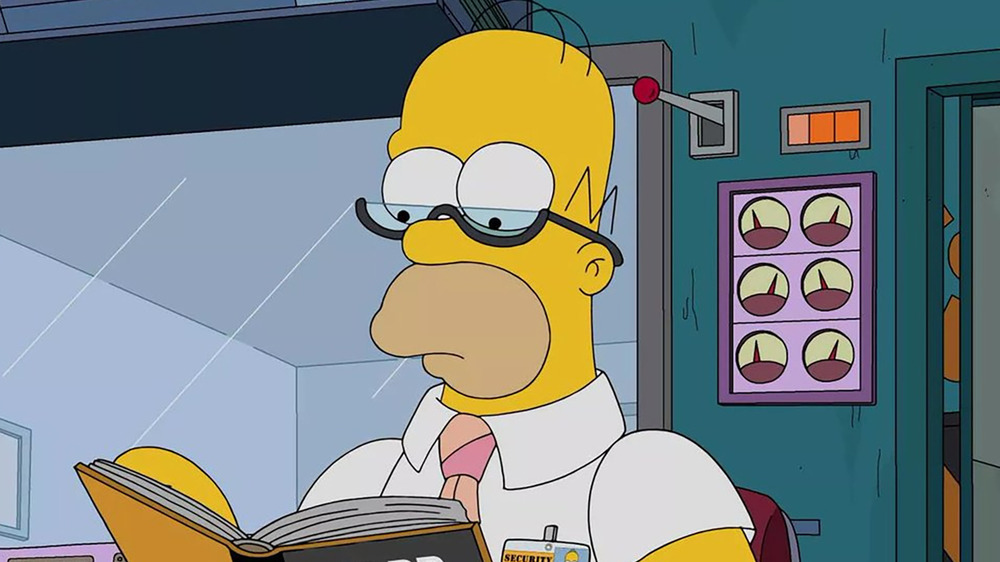

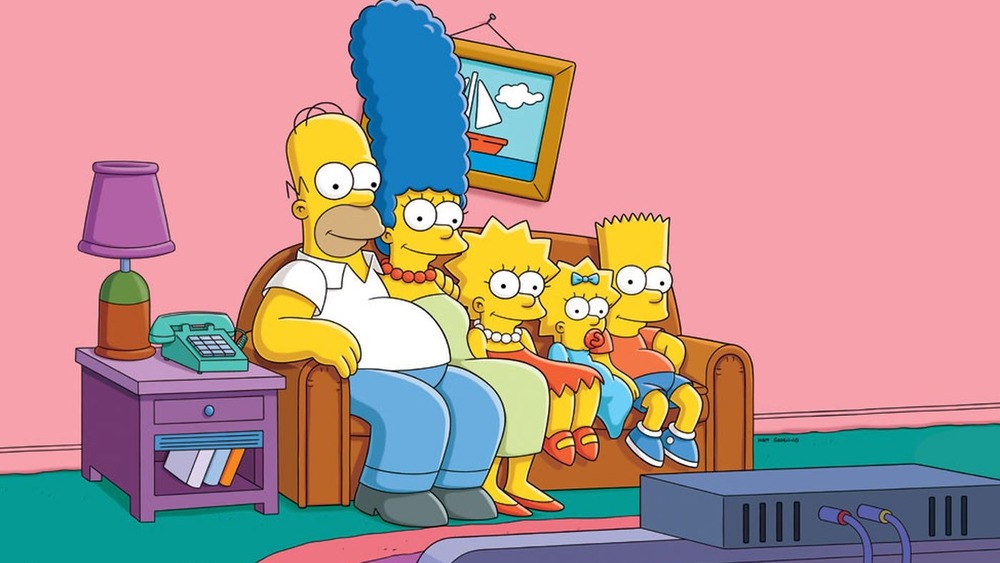

The Simpsons has been on the air for more than 30 years. It has set numerous longevity records, won just about every award possible, and influenced mass culture, leading to more sophisticated sitcoms and proving that animation can be a viable, adult-oriented primetime medium. The show is ostensibly about the Simpsons, an average American family led by two parents, Homer and Marge, living in Springfield. On the surface, both the Simpsons and their hometown are normal, but that mundane veneer belies a whole lot of weirdness. This makes the family and their environment ideal conduits for Simpsons writers to satirize nearly every aspect of modern life.

All that comedy requires an awful lot of world-building. So much is packed into each of The Simpsons' 700-or-so episodes that sometimes, even the most hardcore Simpsons fans end up with questions about the universe of the show, the history of the characters, and what it all means – and this is a show with an extremely devoted following. But we've got the answers to even the trickiest Simpsons queries. Say "D'oh!" no more and "Mmmmmm" instead to these cromulent resolutions to embiggen your Simpsons knowledge.

Where is Springfield, anyway?

It's probably the most hotly debated question in Simpsons fandom: Just where is the nuclear-powered, monorail-enhanced, Krusty-loving mid-sized city of Springfield supposed to be located? The answer is everywhere ... but also nowhere. Springfield doesn't correspond to any actual place, which allows the show's writers to have fun. The city gains whatever geographical features it needs to advance the plot of any given episode, and remains able to brazenly and hilariously disregard any contradictions that may create. Springfield is apparently situated so north that it regularly endures winter weather, west enough that football begins on Sunday mornings, is home to both a Southwestern-style canyon (Springfield Gorge) and a snowy mountain (the Murderhorn), and is in a state with 10 cent bottle deposits. One of the few locales that contains all of these features is Oregon, the birthplace of Simpsons creator Matt Groening and one of dozens of U.S. states home to a town called Springfield.

"Springfield was named after Springfield, Oregon," Groening told Smithsonian Magazine. "When I was a kid, the TV show Father Knows Best took place in the town of Springfield, and I was thrilled because I imagined that it was the town next to Portland, my hometown. When I grew up, I realized it was just a fictitious name." Groening further selected Springfield as his show's setting because it's so common and relatable. "I thought, 'This will be cool; everyone will think it's their Springfield.' And they do."

Why don't the characters on The Simpsons age?

The Simpsons operates on a strange timeline: Characters don't seem to get any older. When the show debuted in 1989, Maggie Simpson was an infant. As of 2021, Maggie is ... still a baby, and not, as math would dictate, 32. It's not that time doesn't pass in The Simpsons — the show accounts for cultural shifts like big-budget superhero movies and smartphones — but everyone is roughly the same age they've always been, bringing with it the implication that 700 episodes' worth of adventures have all occurred over the last few months in The Simpsons timeline. This is all further complicated by the changing and contradictory flashback episodes of the show — Homer and Marge initially met in high school in the '70s, but Homer has also been glimpsed as a grunge musician in the '90s. And then there are those flash-forward episodes, which show that, at some point, everybody does get older.

One theory states that Springfield is located on some kind of complicated tesseract, which makes time pass differently inside of the town than it does in the world around it. But really, it's just that The Simpsons is a cartoon. Other sitcoms have no choice but to let their characters age because their actors are real people who age in real time. Because Simpsons characters are figures on a page or an animation cel, they don't have to age, so the writers don't make them.

How does pollution not kill everyone in Springfield?

Springfield is a heavily polluted place. The local government's lack of interest in going after the source of the problem — C. Montgomery Burns and his waste-spewing nuclear power plant — is a great way for writers to satirize American politics, regulatory law, and big business. There are many factors making Springfield toxic: Burns' plant routinely dumps glowing green ooze into rivers, and abandons leaking barrels of the stuff around town. His own gubernatorial campaign is derailed by the discovery of a three-eyed fish in a river he polluted. The atmosphere is bad too, what with the continuously burning Springfield Tire Fire — the chemicals in the air are so bad, they shrink a deadly comet to the size of a chihuahua. The plot of The Simpsons Movie even involves the Environmental Protection Agency cutting off the filthy and dangerous Springfield from the rest of the world.

This begs the question: How can the residents of Springfield continue living in such a town without dying or, at the very least, mutating? One could argue that they're just used to it. Most of the prominent Simpsons characters are lifelong residents of the town, receiving increasing amounts of pollution for so long that their bodies have adapted. There's also the possibility that they've absorbed all that toxicity, but haven't gone unscathed — the pollution could be why everybody has yellow skin, bulging eyes, and only four fingers on each hand.

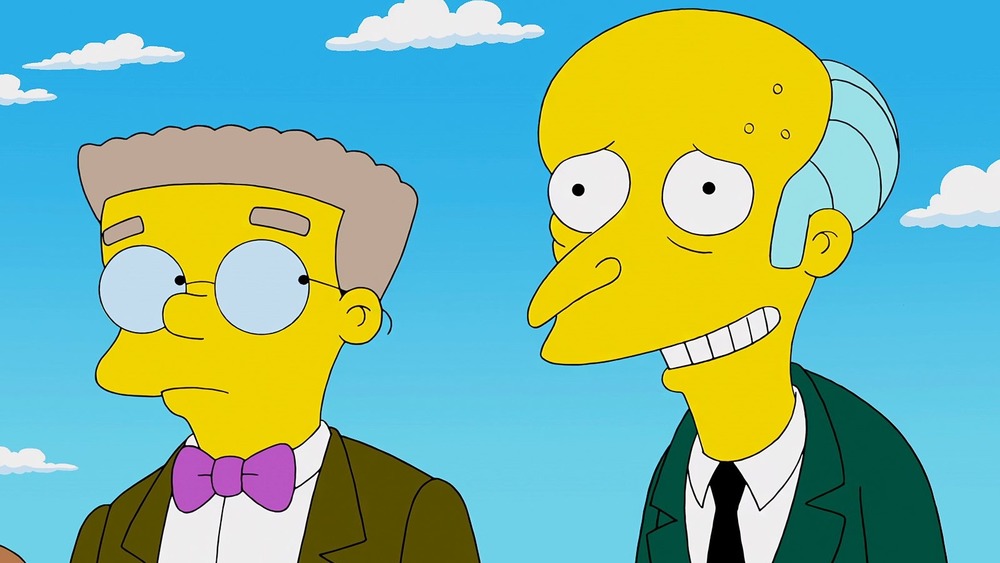

How old is Mr. Burns?

Mr. Burns is ancient. Like a real-life elderly man, the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant owner (and most evil man in Springfield) is cagey about his precise vintage. His birth year has been stated as 1881, 1886, and 1891, and he appears to be about 10 in a flashback to 1909. He's stated his age as 81, 89, and 104, but his ATM password is four digits long, same as his age.

His exact age doesn't really matter, just the fact that he's a deranged old man hopelessly out of touch with the mainstream. He seems like an 19th century robber baron, plucked out of his time and deposited into the present day (or the past couple of decades, depending on the Simpsons season). Antiquated cultural references are just plain hilarious when they come out of Mr. Burns' mouth, be they the names of pro baseball players who have been dead for 100 years, the way he says "Ahoy, Ahoy!" when answering the phone, or how he asks the post office to send his letter "by auto-gyro to the emperor of Siam," post-haste. Landing on a specific number for Mr. Burns' year of birth would severely limit Simpsons writers, forcing them to be accurate in their old-timey references. And that would be a tragedy.

Why doesn't Marge leave Homer?

The Simpsons has been going strong for three decades, and since there are only so many sitcom plots out there, the show has occasionally repeated itself. One idea its writers have explored on multiple occasions: The possibility of Homer and Marge splitting up. These high-school sweethearts obviously love each other very much, but they're only human and they occasionally almost give in to temptation. For example, Homer nearly has an affair with Mindy, a Springfield Nuclear Power Plant worker who is as big of a glutton as he is, while Marge almost runs away with Jacques, a charming French bowling instructor. From a logical, outside-looking-in standpoint, many viewers couldn't blame Marge for dumping Homer — he's a selfish, unpredictable lout, after all.

However, The Simpsons is a sitcom in the classic mold. By the end of the events of each episode, things are right back where they started. The show is about a married couple, though a realistic one that faces tough challenges, and to split up Homer and Marge would fundamentally change the nature of the show and require an entirely new approach going forward. It makes more sense — and is more entertaining — for writers to almost or temporarily split up the couple, or show them dealing with their problems while sticking together, demonstrating their strong bond. Homer and Marge are "endgame," and nothing is going to change that, not even a lady Homer or a rakish bowler.

How involved was Michael Jackson in an early Simpsons episode?

Over the years, dozens of Hollywood bigshots have turned up on The Simpsons to play themselves. One of the first was the King of Pop himself, Michael Jackson. Well ... sort of. According to John Ortved's The Simpsons: An Uncensored, Unauthorized History, Jackson called executive producer James L. Brooks and volunteered to use his musical gifts to write a number one hit single for his favorite character, Bart Simpson. He also wanted to appear on the show as himself, but executive producer Sam Simon wouldn't allow it, owing to an unofficial policy that celebrity guest stars had to play a character. "So they came up with this idea that Michael Jackson would play an insane asylum guy who thinks he's Michael Jackson," staff writer Brian Roberts said.

Here's where things get confusing. In the 1991 episode "Stark Raving Dad," Jackson voiced Leon Kompowsky, who helps Bart write and sing a birthday song for Lisa. But that's not Jackson singing — it's his favorite Jackson impersonator, Kipp Lennon. Jackson eschewed a credit for his voice work too, with Leon credited to "John Jay Smith." But Jackson did fulfill his promise to get Bart a hit record. The novelty song "Do the Bartman" topped the U.K. pop chart in 1992. A musician named Bryan Loren wrote it, but Jackson came up with the title and prompted the inclusion of the line, "If you can do the Bartman, you're bad like Michael Jackson."

Why are they named "the Simpsons"?

In the late '80s, powerful Hollywood producer James L. Brooks wanted animated shorts to air as filler on The Tracey Ullman Show. He invited Matt Groening to his office to discuss adapting his indie comic strip, Life in Hell. As Groening waited for Brooks to call him in, he realized that he didn't want to lose the rights to his creative masterwork, so he came up with a new pitch in minutes. His concept: A cartoon about a dysfunctional family. Thinking fast, he named the characters after his own family members. Groening's parents were named Homer and Margaret, and he's a brother to Lisa and Maggie. By that logic, the other kid should be named Matt, but Groening named him Bart. "Back in high school I wrote a novel about a character named Bart Simpson. I thought it was a very unusual name for a kid," he told Smithsonian Magazine. He also liked how it would sound yelled by an angry dad, like Homer: "Bart sounds kind of like bark — like a barking dog."

It worked out nicely for Groening that his original Bart Simpson had a last name that would work for his new cartoon. "I took that name from a minor character in the novel The Day of the Locust, by Nathaniel West," Groening explained. "I thought Simpson was a funny name in that it had the word 'simp' in it, which is short for 'simpleton.'"

Why is a passé relic like Krusty the Clown so important on The Simpsons?

Since it entered production in the late 1980s, The Simpsons was conceived of and written by a staff of people who grew up absorbing the culture of the mid-20th century. As such, they made fun of that kind of stuff on the show. This explains the entire character arc of Troy McClure: He's a washed-up actor from '70s B-movies reduced to hosting infomercials by the '90s. This also justifies the presence of Krusty the Clown.

In the '90s, adult Simpsons viewers were far more likely to have grown up watching locally produced kiddie TV shows hosted by guys dressed like pirates, cowboys, or clowns. The famous Bozo had a popular Chicago show, for example, and Rusty Nails had one in Portland, Oregon, of which Simpsons creator Matt Groening was a fan. Krusty alludes to that era of television, which has faded farther into history over the years The Simpsons has been on the air. But Krusty remains a major character on the show, a vestige of early Simpsons baked into its DNA, despite no longer being a cultural touchstone for the average viewer. Krusty's purpose also remains unassailable: He's a vehicle through which writers satirize television, as well as corporate greed, as the clown runs a mass-merchandising empire and a fast food chain. Those themes remain evergreen.

How is a Fox show able to tease Fox and Fox News so much?

The Simpsons is a proud agent of satire, and its writers will make fun of any prominent institution they please. No one is safe from The Simpsons' vitriol — not even its very own Fox network, or its corporate cousin, Fox News. Examples of the former include Homer whining how Lisa won't let him watch Fox because it "owns a chemical weapons plant in Syria," and the depiction of the brutal murder of a network censor. How is it that The Simpsons doesn't seem to ever suffer any fallout for teasing its bosses? Well, the right to do so is written into the production's agreement with the network. Simpsons producers are entitled to full creative control, with Fox executives unable to give feedback or cut scenes.

As for Fox News, The Simpsons, and its arrangement with Fox, predate the cable news outlet. The Simpsons has been quite critical of the conservative-leaning news channel, and while some higher-ups on the corporate chain have tried to stop the show from making its jokes, they have not succeeded. They've certainly tried, however: At 2017's San Diego Comic-Con (via The Hollywood Reporter), Simpsons creator Matt Groening said his staff was asked to go easy on Fox News, with an internal lawsuit threatened, after an episode quipped that Fox News was "not racist, but number one with racists."

Why do fans think The Simpsons declined in quality?

Most television shows — particularly those that air hundreds of episodes — don't fire on all cylinders right away. The Simpsons needed a couple of seasons to find its rhythm and unique comic sensibility. Generally speaking, Simpsons fans agree that the show's "Classic Era" or "Golden Age" runs from its third season through to its eighth season. Indeed, some of The Simpsons' most remembered episodes were produced during this period: Of the top 50 highest-ranked installments, according to IMDb, 48 date to the Golden Age, including "Marge vs. the Monorail," "Mr. Plow," and "Homer at the Bat."

Determining which Simpsons seasons and episodes are better than others is highly subjective, but there are concrete things fans can point to that explain why the show supposedly went downhill. It's debatable that the show got worse, but it certainly changed — as it logically would — after the departure of many "Classic Era" writers and producers. By 1997, multiple heavy-hitters had moved on from the show, or stopped actively composing episodes of The Simpsons, including Sam Simon, Mike Reiss, Jay Kogen, and even creator Matt Groening.