'90s Movies That Became Unwatchable With Age

The '90s were one of the most bustling and exciting eras ever for filmmaking. Between the apogee of American indie cinema, the dawn of the CGI-heavy fantasy blockbuster, the emergence of influential arthouse luminaries like Wong Kar-Wai and Krzysztof Kieślowski, and the greatly increased number of female directors, it was a great decade in which to be a movie buff of any kind. Like any decade, however, it had its share of duds — both immediately obvious ones, and ones that took some time to start getting moldy.

For a period that ended not that long ago, there's a surprising number of films from the '90s that have aged all too rapidly, even to the point of becoming unintentionally punishing watches. This list compiles 14 originally popular and beloved films – including several Oscar nominees and winners — that now stand as head-scratching testaments to how much has changed culturally, politically, and socially since the first post-Cold War decade.

Boys Don't Cry

Although it broke ground as the first mainstream American film about a trans man, Kimberly Peirce's "Boys Don't Cry," based on the tragic 1993 murder of Brandon Teena (Hilary Swank), has little remaining educational or representational value. Leave aside, if you will — and you absolutely mustn't — the fact that Teena was played by a cisgender woman, as was sadly commonplace in Hollywood until just a few years ago. Even ignoring that, "Boys Don't Cry" now stands out as miserabilist and trauma-obsessed — a product of a time when the very existence of trans men was treated as a cinematic curio, an oddity to be sensationally exploited.

Contemporary trans male viewers have significant issues with the film, with many finding that it ultimately reduces Teena to a pitiable victim, with his murder as the focal point of interest in his life, while exhibiting an utterly wrongheaded understanding of transmasculine experiences. Even the script and the direction themselves seem to fundamentally view Brandon as a delusional woman, constantly emphasizing dysphoria, deceit, and strained performance as the main defining features of his existence.

Never Been Kissed

Raja Gosnell's popular rom-com "Never Been Kissed," which Drew Barrymore herself has called her best film role, follows Josie Geller (Barrymore), a journalist who's assigned to go undercover at a high school ... and ends up falling for her English teacher, Sam Coulson (Michael Vartan), while disguising herself as a student.

Sure, one could argue that none of it is really weird because Josie is actually 25, which makes her a full-grown adult just a few years younger than Sam (Vartan was 30 when the film was released). But that wouldn't change the basic fact that the film tries to wring romance out of a teacher falling in love with his student, while under the assumption that said student is just 17 years old.

As many critics have observed in the deeper reckoning with relationship power imbalances of the post-#MeToo era, it's objectionable enough for teachers to flirt with their fully adult students in universities, let alone for a high school teacher to flirt with a student he believes to be a teen. Criminal or not, Josie, that man is a creep, and "Never Been Kissed" celebrates their romance.

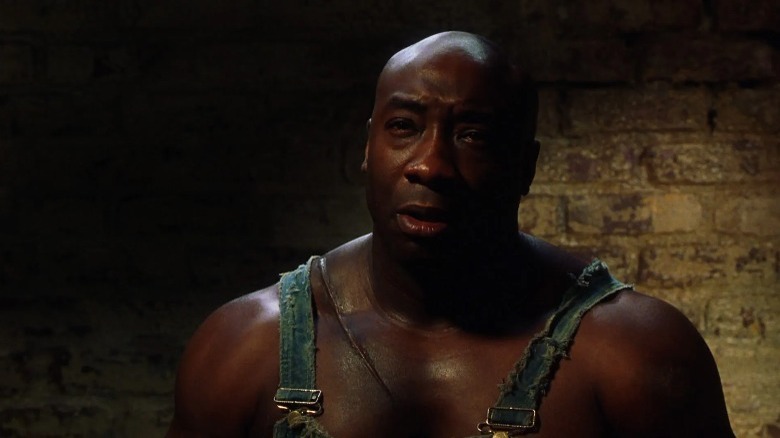

The Green Mile

In a cultural context rife with penal populism, it's no wonder that a film like 1999's "The Green Mile" — which humanizes an innocent death row inmate and decries his execution — was once seen as a searing critique of capital punishment.

But putting nostalgia aside for a moment, just how far does the film really go in its politics? With all the public has since learned about the U.S. prison industrial complex and how it preys upon the poor and marginalized and traps them in a cycle of violence and hopelessness, several commentators and fans now see the film's protest against the condemnation of unambiguously innocent people as not much of a truly principled anti-capital-punishment stance — less a resolute "death penalty is bad" than a half-hearted "death penalty has issues in application." (Is there anyone in the world who believes innocent convicts should be executed?)

As if that weren't enough, as brilliant as Michael Clarke Duncan's performance is, the character of John Coffey is widely remembered as a textbook Magical Negro — a saintly figure whose horrifying suffering is sensationalized for the tear-jerking benefit of a presumed white audience.

Life Is Beautiful

One of the most commercially successful non-English films of all time in the United States, "Life Is Beautiful" became a sensation upon its release in 1997, winning three Academy Awards. Its story of a Jewish concentration camp prisoner (Roberto Benigni) who uses humor and games to shield his son (Giorgio Cantarini) from the camp's horrors was considered a life-affirming and whimsical new take on Holocaust cinema.

In retrospect, it was really one of those "What was everyone thinking?" cultural moments. As retrospective reviewers have frequently remarked, director and star Roberto Benigni — who is very much not Jewish — handles the Holocaust with a tone that veers beyond levity and right into tastelessness, distorting the reality of the Holocaust to support the comedy and family-movie-night cuteness he's angling for. When the time comes for stark reality to set in, the film also depicts it as sentimentally as possible, exploiting the tragedy for cheap mass-appeal sentiment. No wonder "Maus" author Art Spiegelman coined the term "holo-kitsch" after watching it.

Runaway Bride

The oddity of 1999's "Runaway Bride" begins with its premise. Cynical New York City newspaper columnist Ike Graham (Richard Gere) is tasked with writing an in-depth article about local Maryland celebrity Maggie Carpenter (Julia Roberts), who became notorious for abandoning a series of men at the altar. Ike then begins to shadow Maggie everywhere she goes, offering snide comments about her life in the process.

Not once does the film stop to consider if Maggie actually needs to get married; it's simply assumed that she must, with her repeated "failure" to do so thus making up a problem to be deciphered as she leafs through some of the most twisted weddings in movie history. But never mind that old-fashioned bridal-imperative plot. The reason the film has become so insufferable as to inspire entire, massive Reddit threads gawking at how badly it's aged comes down to its very structure — which curses Maggie with being constantly stalked and pestered by a snarky male lead who purports to be "misanthropic," but is really just unrepentantly sexist. Rom-coms don't need to be progressive to work, but they need to be charming. An obnoxious know-it-all like Ike could only be considered charming in a bizarre cultural context like the '90s anti-feminist backlash.

Blank Check

To put it plainly, "Blank Check" features a romantic subplot between an 11-year-old boy and an adult woman seemingly well into her 30s. While the film's whole comedic premise hinges on the contrast between the juvenile Preston Waters, a.k.a. "Mr. Macintosh" (Brian Bonsall), and the adult environments he uses his newfound money to navigate, the decision to also have Preston navigate grown-up love has rendered "Blank Check" horrifying to contemporary reviewers.

For starters, the romance between Preston and FBI agent Shay Stanley (Karen Duffy) is, of course, blatantly predatory — and, just as you're convincing yourself it's all silly make-believe, the characters actually go and share a kiss. What really baffles critics and movie buffs in retrospect, though, is that the film treats the whole situation like it's no big deal, a quirky little gag at most — both normalizing Preston's abuse and infantilizing Shay, whom we're to believe is a normal, healthy woman who just happens to fall for the charms of an 11-year-old child. Audiences didn't seem to mind at the time; the film became a healthy box office success. 30 years later, it's hard to imagine how so many people could have gotten past the ickiness of it all.

Forrest Gump

Three decades later, it's not rare for critics to describe "Forrest Gump" as an ableist film. Forrest's (Tom Hanks) caricatural, plot-servicing intellectual disability is just undefined and implicit enough to be used by screenwriter Eric Roth and director Robert Zemeckis for whatever dramatic or comedic purposes they want while also avoiding the heat of misrepresenting and mocking any specific real-world disability (a maneuver that would be one-upped years later by "The Big Bang Theory," which strenuously avoided labeling Sheldon). That's not the only part of the film that irks now, though.

Several notable critics have analyzed "Forrest Gump" as a case study in the reactionism of the early '90s — an all-in-one pack of everything that was ugly and questionable about that nominally liberal, yet fundamentally conservative era of American culture. Seen through a modern lens, the entire film can be read as a parade of outdated values and reductive ideas about the U.S. and its past: Forrest is depicted as a hero for being a complacent and diligent witness to historical events like the Vietnam War, while Jenny Curran (Robin Wright) gets punished and villainized for going against the system, embracing the sexual revolution, and living life in her own terms. It's a love letter to post-Cold War conformity, and has aged accordingly.

Falling Down

A critical and box office success, Joel Schumacher's "Falling Down" was taken very seriously in 1993 as an expression of a certain kind of "everyman" rage. William Foster (Michael Douglas), the "average" middle-class fella who goes on a violent rampage across Los Angeles after getting stuck in traffic, was seen by critics as an avatar for an overarching American social frustration.

What a difference 31 years make. Seen today, "Falling Down" comes off as goofy, superficial, and histrionic to many reviewers. Foster's anger is so vague and all-encompassing that it's all but sociologically meaningless, an incoherent screed against the whole darn world. What little anthropological interest the film possesses, in fact, is limited to its quiet, obtuse, yet unmistakably simmering hate against minorities — from the various people of color who antagonize Foster and get in his way, to the gender culture that emasculates him by forcibly keeping him away from his daughter and ex-wife.

The film tries to disguise its bigoted slant by pitting Foster against a neo-Nazi store owner, but, seen in 2024, there's no getting around what "Falling Down" is. As carefully analyzed by critics such as LA Weekly's April Wolfe, it's the prototypical victimization narrative for the white middle-class American man who believes himself to be a societal martyr.

Pocahontas

Like most of Disney's animated visitations into marginalized cultures, "Pocahontas" took great pains to at least seem respectful to the people it depicted. Native American voice actors were cast in all Native roles, and descendants of the Powhatan people were brought in as consultants. But in tackling a subject as weighty as the European colonization of North America through a simplified and commercialistic Disney lens, the film fumbled the bag about as epically as it could.

Powhatan authors have written at length about how Disney's take on their culture and history was utterly distorted and self-serving — the whole movie relies on inaccurate history for its plot. But it doesn't even take any research to wince now at the film's centrist, both-sides-are-at-fault approach to the Native American genocide, which often bothers contemporary Disney fans on Reddit and elsewhere. Although the English settlers are the clear villains, the Powhatan leaders and warriors are also framed as radical and irrational in their blanket distrust of all white men, and the film's ultimate tragedy is the forbidden love between Pocahontas and John Smith — as if it were all a mere matter of Montagues and Capulets. In Hollywood cinema of the '90s, it seems that racism and colonialism were less historical tragedies than individual conflicts.

The Waterboy

If you think Adam Sandler isn't the most trustworthy co-writer and star for a broad comedy about an ambiguously disabled man, you'd be right. There isn't much mystery to the staleness of "The Waterboy," which continues to bother viewers in online spaces like the r/disability subreddit. Starring Sandler as Bobby Boucher, a water boy-turned-linebacker whose characterization is marked by yet another noncommittal, autism-aping unnamed disability, the film is your expected string of ableist jokes passed off as good-natured ribbing, topped with a condescending Magical Disabled Person narrative that's meant to be uplifting.

Before you get to the marginally empowering ending where Bobby's bullies are exposed as the greater fools, you'll have to endure plenty of mean and othering humor at Bobby's expense — a relic of an era when intellectual disability was considered an accepted punching bag for comedians. And that's not even getting into all the casual racism, which is just one of the many recurring issues that some people can't stand about Adam Sandler movies.

Jerry Maguire

Cameron Crowe makes crowd-pleasing, life-affirming, proudly sentimental films in which themes and relationships are painted in bright colors. In some cases, his sensibility yields veritable modern classics. In others, it results in turkeys — but some of those turkeys aren't immediately apparent as such. "Jerry Maguire," for one, was largely beloved upon release.

Nowadays, many critics are considerably less kind to the film, sometimes even citing it as an example of Clinton-era publicity for an idealized version of corporatism that never really existed before or since, with a facile outlook on the sports management industry. Although "Jerry Maguire" impressed audiences and critics in 1996 as a mainstream American movie that dared to mildly criticize the country's economic system, with its Tom Cruise-played protagonist as a symbol against the dehumanizing excesses of capitalism, the film is still very much pro-capitalism. Its ultimate worldview falls more on the side of, "let's improve the system with kindness" than honest reckoning.

On top of all that, the romance plot between Jerry and Dorothy Boyd (Renée Zellweger) relies too heavily on the corny love-conquers-all '90s trope, which Hollywood has done well to (mostly) leave behind. "You had me at hello" just about sums up Dorothy's depth as a character.

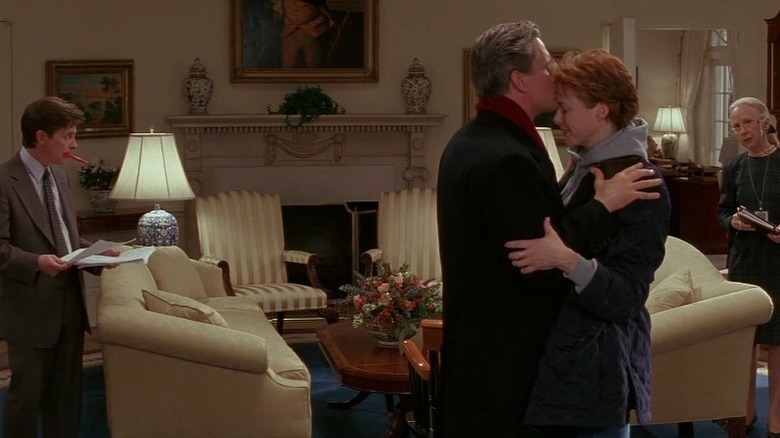

The American President

The idea behind 1995's Aaron Sorkin-penned, Rob Reiner-directed "The American President" is understandable: Take the mythologized, inaccessible figure of the U.S. head of state and humanize him, showing that, at the end of the day, he's just a guy bumbling his way through love like you and me.

The problem, of course, is that only someone with a view of American politics as rose-colored as Sorkin's could see the president as an everyman. He's an unimaginably powerful figure whose actions and decisions hold sway over the lives and deaths of millions around the globe. In the current political climate, "The American President" is frequently taken to task by critics for handwaving all that away, treating the President's duties as any rom-com would treat the professional turbulences of a celebrity protagonist — like plot furniture.

As reviewers have since noted, the ascription of fundamental nobility to President Andrew Shepherd (Michael Douglas), who remains likable and sympathetic even as he's ordering a missile strike on Libya and killing innumerable civilians — he feels guilty about it, after all — stamps the movie with an unmistakable pre-Lewinsky, pre-9/11 political naiveté, an idealism that could only have made sense to audiences in that very specific historical moment.

Ace Ventura: Pet Detective

The '90s visual and comedic corniness, liberally sprinkled misogynistic humor, and completely uncalibrated Jim Carrey mugging make "Ace Ventura: Pet Detective" enough of an endurance test for contemporary tastes, as critics who bothered to revisit it have consistently observed. But then the film gets to its big, mic-drop joke, and sinks to depths of open hate and cruelty that feel genuinely dizzying to witness nowadays.

The film's big twist comes when Ace Ventura (Carrey) finds out that Lois Enhorn (Sean Young), the attractive and flirtatious lieutenant who had previously made advances towards him, is actually the villainous Ray Finkle, who — as the film puts it — went through surgical and hormonal modifications to disguise himself as a woman. Ace reacts to that finding with abject, heaving, writhing disgust — probably the most over-the-top reaction of disgust ever depicted in an American studio comedy.

It makes no difference that the film never uses the terminology "trans woman," nor that the scene is meant as a parody of 1992's "The Crying Game." In that moment, "Ace Ventura: Pet Detective" crystallizes the notion that transgender women are the world's most disgusting creatures — all in the name of comedy, naturally. It's not just impossible to laugh; it's unbearable to watch.

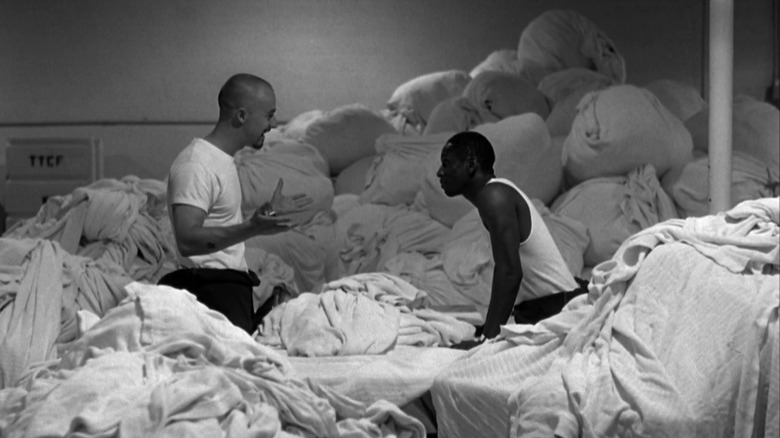

American History X

It's an enormous responsibility to make a film about neo-Nazis — especially one which, like Tony Kaye's "American History X," is primed to occupy such a visible cultural position as to become a mainstream reference point on the subject. Kaye's film originally garnered very positive reviews, but some modern critics feel that it may not have been up to the task.

The problem that contemporary reviewers have identified with Kaye and screenwriter David McKenna's approach is that they don't persuasively deconstruct and fight the hate they're depicting. Virtually no depth or substance is afforded to Derek Vinyard's (Edward Norton) process of overcoming his racism; to hear the film tell it, all it takes for Derek to overcome a lifetime of indoctrination is becoming friends with Lamont (Guy Torry) in prison because Lamont makes him laugh.

This simple realization — hey, one Black guy is cool — isn't just unconvincing as a plot catalyst for Derek's change; it's insufficient as discourse. The entire film up until then pays unflinching, horrifying lip service to white supremacist rhetoric, letting Derek and other Disciples of Christ (D.O.C.) members spew their venomous words and false arguments freely. Following all that, the introduction of one sympathetic Black man scarcely counts as a meaningful rebuttal. "American History X" may have once seemed like a potent exploration of a shocking fringe mentality. But now that white supremacism has re-emerged into the American mainstream, the film's depiction of it seems superficial at best — and actively irresponsible at worst.