That's What's Up: Why Batman Being An Atheist Is More Complicated Than It Seems

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: They announced that Batman is an atheist. I think it's terrible, as it reinforces the idea of atheism as only being embittered with God after a tragedy. What are your thoughts on Batman and religion? Keep it vague? — @Ettore_Costa

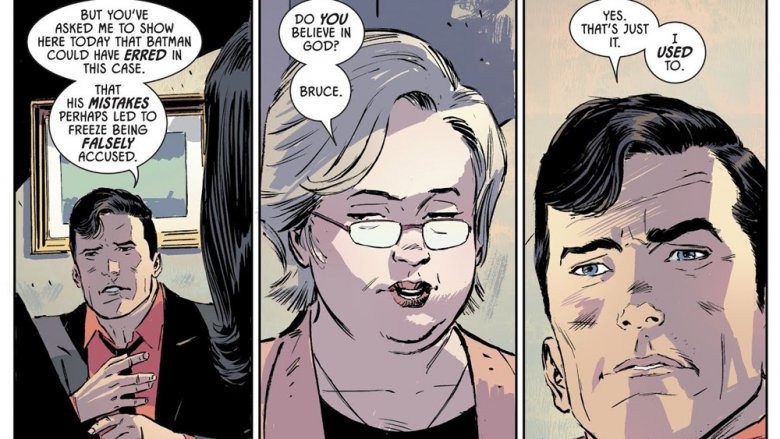

The scene in question comes from the recently published Batman #53 , and even though there's a panel that literally has Bruce Wayne saying that he "used to" believe in God and that he "put aside believing in a deity" after his parents died, I'm not sure describing it as a comic where Batman announces his atheism is the right way to describe it. For me, that issue was less about defining Batman's personal faith than it was about describing Bruce Wayne's relationship with Batman as a concept, and how Gotham City sees him as this infallible and unknowable force. But we'll get back to that in a second.

Whether or not you want to take Batman's atheism as gospel (so to speak), it does raise a lot of questions about the relationship between religion and superheroes in general, and Batman in particular. I think you're right about one thing, though: Batman probably shouldn't be an atheist — or at least, not as we understand it here in our world.

Higher (Super) Powers

That's not me trying to project anything of myself onto the character, either. Despite my recent tendency to quote Acts 8:21-23 at anyone who tries to tell me that Batman & Robin is the worst Batman movie, I'm not really a believer myself. Instead, my feeling on the matter is that in the world where Batman lives, belief in God (and lowercase gods, and ghosts, and all the supernatural stuff that's a little more up for debate here in our world) isn't really a matter of faith. There's empirical evidence for it everywhere you look, especially for someone like Batman.

In the DC Universe, the supernatural exists, full stop. Most of the time, that means that when Gentleman Ghost shows up to rob a bank, he's exactly what he says he is, and when there's a team-up with Zatanna or John Constantine, they're actually doing magic and not just pulling off some complicated illusions. It doesn't stop with all the wizards he has on speed dial, though. He exists in the same world as Wonder Woman, who literally gets her powers from the Greek gods, who are real enough to have fought the Justice League on multiple occasions. And really, are you going to tell Wonder Woman that they're not actually gods and just extra-dimensional beings that were once worshipped as such? Split those hairs as fine as you want, but the deeper you go into that debate, the more it's clear that there's no real functional difference.

But that, of course, is just the stuff that we here in the real world — or most of us, anyway — regard as mythology. The thing is, if you want to talk about actual Judeo-Christian capital-G God, then He is every bit as real as everything else in these stories. I mean, back in the '90s, there was literally an angel on the Justice League.

Zauriel makes a compelling case

Like, an actual angel. From Heaven. His name was Zauriel, and he was a Guardian Angel who came to Earth because he fell in love with the woman he was watching over, and wound up becoming a superhero because having wings, a flaming sword, and a direct line to the Almighty is at least as good as whatever it is that Aquaman brings to the table.

Point being, Zauriel — and Etrigan the Demon, and Neron, and the Spear of Destiny, and everything else that's drawn from Christianity — are absolutely, 100% real in the world where Batman exists. For him, not believing in God makes about as much sense as not believing in aliens when Superman and the Martian Manhunter come over every year for Thanksgiving. It would be like not believing in England even though Alfred is standing right there. Why do you think he has that accent, Bruce? It's the same reason that Zauriel showed up to help you fight a dude who was twelve feet tall, covered in eyes, and had the head of a bull: that's just how things are where he's from.

Whatever else he might be, Batman is first and foremost a detective — the world's greatest, in fact. He's a person who puts together clues to solve mysteries, and ignoring all of that evidence around him for the definitive existence of the supernatural just doesn't make sense. Batman, almost by definition, has to believe that this stuff is real, in one form or another. But the fact that all of this definitely exists raises its own set of questions that make things even more complicated.

If everything is real…

It's a massive understatement to say that superhero comics draw heavily on religious imagery, but that's not limited to a single religion. There's a strong undercurrent of Judeo-Christian ideas running through them, but that's largely because it's a genre created in America, where those ideas have a pretty strong influence on... well, pretty much everything. Regardless of our personal beliefs, there's a shared cultural context that runs through literature that pretty much ensures that we can all understand the symbolism when there's a reference to, say, Adam and Eve, or crucifixion imagery. When the Spectre shows up and announces himself as the embodiment of the Wrath of God — another pretty definitive piece of evidence that Batman has experienced firsthand — we all know what that means.

But here's the thing: that's not the only set of religious imagery that superhero comics draw from. Like the rest of literature, the medium takes influences from everything else that makes up our shared cultural context, and that extends to other beliefs. As much as we all get the reference when someone says "thou shalt not," we also know what it means when Wonder Woman heads down to the underworld to talk to Hades, or when Amatsumikaboshi shows up, even if that one might require a footnote for a lot of readers.

There's probably not a better example of this than Shazam. He draws his power from five figures drawn from Greco-Roman mythology, including Zeus and Hercules, and then tacks on the Wisdom of Solomon, a figure some of you may remember from the Old Testament, which you can find in a book that is pretty explicit about Zeus not being a thing. That's not an element unique to the DC Universe, either. Across the street at Marvel, Thor and Hercules aren't just dudes using those names, they are the actual, real, immortal Thor and Hercules, who come complete with their respective pantheons, and all the mythology that goes along with them. Even though those stories conflict each other, both of those dudes are absolutely real, to the point that they're both on the same superhero team.

...then what's really real?

That raises its own complication, though. Batman doesn't just live in a world where God is pretty undeniably real. He lives in a world where every god is undeniably real. When Wonder Woman fights Ares, he's no less real than when Zauriel helped the JLA fight Asmodel. The flipside to that, of course, is that it's no more real, either.

That's part of the luxury of fiction, but like a lot of things about superhero stories, it's something that doesn't quite work when you try to apply real-world logic. Even weirder is when you try to apply superhero universe logic to the real-world version of those ideas. To use the Marvel Universe as an example, Thor is the actual, literal God of Thunder, who was — and is — venerated as a deity. In the context of the fictional universe around him, however, he's functionally no different from, say, the Hulk, or Captain America. Plus, if you want to get really complicated about it, you can throw in other teammates like Doctor Strange and Ghost Rider, a wizard who invokes eldritch powers and a dude possessed by a literal demon from Hell, respectively. They fill the same roles, do the same things. Does that mean that in their universe, they should occupy the same space in culture that deities do in ours?

It's one thing to look at these ideas in the context of a figure, like Thor, that most modern audiences see as a piece of folklore. If you start going down that rabbit hole, though, it's tough to figure out when to stop. Not to get too blasphemous here, but Batman knows more than one person who can walk on water and came back from the dead after sacrificing their lives to save people. Does that mean that in his world, that means that the figures we worship in ours should be considered no different from Superman? It's an extremely complicated question that's almost guaranteed to make someone angry no matter how you answer it, but it changes the way you have to look at the way these characters interact with religion. And that's before you get to the gods that were created specifically for comics. Like, you know, the New Gods. There's not a lot of ambiguity in that title.

Vaguely spiritual

In many cases, the answer that creators have found is the one you suggest in your question: leaving things vague. That's not always the best idea, though. It's definitely true a lot of characters, like Superman and Batman, can benefit from keeping certain aspects undefined. It helps them to be adaptable to different stories, and allows multiple audiences to be able to identify with them, and also allows them to interact with other elements of the universe in a way that feels less contradictory.

If Batman expresses a devout belief in God, for example, then that invites him, and the reader, to interact with supernatural and religious elements of those stories in a different way. It's not strictly necessary unless the creators of the stories want it to be, but any time you raise those questions, someone is going to want an answer. Keep it a little vague, though, and he can go on fighting Gentleman Ghost and teaming up with the Demon without having to take up precious space on the page reconciling it with his beliefs.

At the same time, there are plenty of characters who absolutely benefit from defining their religious beliefs. I'm not sure anyone would argue that we lost more than we gained by canonically defining Magneto, Kitty Pryde, and Ben Grimm as Jewish, or by making Daredevil's Catholicism a central part of his stories, and those aren't even the characters who draw their power from any sort of religious elements. It adds to the fabric of their character in a way that can inform their actions, just like any other.

Religion and representation

There are plenty of reasons to use religious beliefs as a building block for a character, and one of the most important is also one of the simplest: representation. As much as you can argue that keeping things vague means anyone can identify with a character, that specificity can add something important — not just to the character themselves, but to the universe around them.

Part that comes from that same shared cultural context that I wrote about earlier. Because of the way pop culture has been formed over the past few centuries, there's a certain set of default aspects to a character that are rarely questioned, and absolutely should be. In terms of religion, that defaults to that same kind of vaguely Christian background that we see in the imagery and references to those stories. The only reason it's notable at all that Batman might be an atheist — or that Daredevil's Irish Catholic, or that Ben Grimm had a second bar mitzvah 13 years after he got turned into a rock monster by cosmic rays — was the default assumption that he wasn't. Defying that default standard, whether it's through religion, race, gender, sexuality, or any number of other very important characteristics, doesn't just make their world seem like a more accurate reflection of ours. It breaks the set of defaults, and in the process, results in a more interesting character.

There's a great example in the form of Dr. Faiza Hussain, a character from the highly underrated Captain Britain and MI-13. Making the bearer of Excalibur and the true heir of King Arthur a Muslim woman is absolutely a statement by her creators, Paul Cornell and Leonard Kirk, but more than that, she represents active choices. Every single aspect of every single fictional character in existence is the result of a choice by a creator — everything. There is nothing about Batman or anyone else that "just happens" to be there, because it's fiction and the people who made it up. The only question is whether something is the result of an active choice or a passive one, and characters that are the result of active choices, the ones with the thought put into them, are inherently more interesting.

Which brings us back to Batman and the question of his atheism.

Dark Knight of the soul

If there's one thing that I've been trying to get across with all this, it's that the interaction between superheroes and religion is complicated. It raises all sorts of questions about mythology and belief, conflicting theologies, and whether faith can even exist in a world where gods are an absolute certainty. That's the reason I read a comic where Batman said that he didn't believe in God and didn't see it as an announcement of Batman's atheism. I got something completely different out of it.

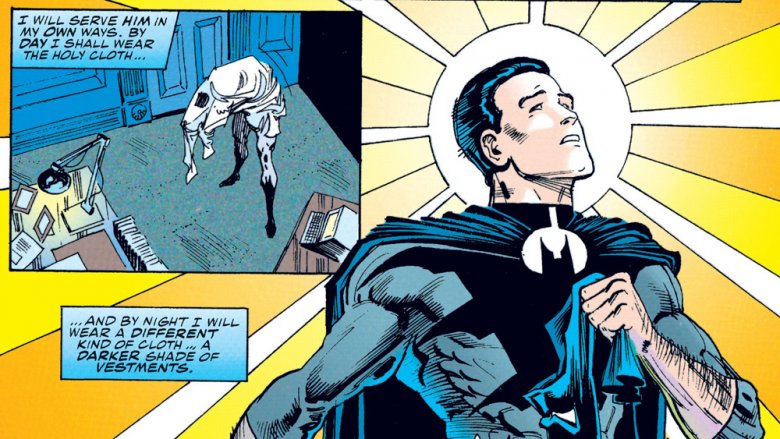

For me, that story wasn't about Bruce Wayne becoming embittered with God after a tragedy, although I think it's more than fair to see that as an element of it. Instead, I saw it as the story of Bruce Wayne dedicating himself to a higher calling. The story of Batman is the story of a person becoming a symbol, of someone rising out of a tragedy and becoming a figure of inspiration that others look to in their most desperate times. I mean, it is also first and foremost a story of a guy in a Dracula costume driving around in a rocket car and punching out alive snowmen and crossword puzzle bank robbers, so take all of this with a grain of salt. Still, those ideas are in there, as undeniable as the pointy ears and bat-shaped boomerangs.

At its heart, the story told in that issue of Batman isn't about a lack of belief. It's about finding something to believe in, coming to question those beliefs, and determining what to do with those questions. And, you know, spoiler warning and all, but he's still Batman at the end of that story, even after grappling with the idea that this symbol to which he's dedicated his life is the product of a fallible human. That's not the story of an embittered atheist. If anything, that's the story about finding something beyond yourself to believe in and working to make it better. And to me, as someone who pretty clearly thinks a lot about the way these stories interact with belief and the quasi-religious nature of heroic fiction in general, that all makes perfect sense.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."