The Untold Truth Of The Return Of The Living Dead

Released in 1985, "The Return of the Living Dead" is one of the rare horror comedies that's genuinely horrifying. As the film tells us, George A. Romero's zombie genre-defining "Night of the Living Dead" was based on an actual military cover-up. And due to a mishap with the transportation, the incriminating evidence is now residing in dust-covered barrels in the basement of a medical supply facility, where Freddy (Thom Matthews) is enjoying his first day on the job.

His bumbling new supervisor, Frank (James Karen), takes him to see the corpse-containing barrels, and before you can say "kicking a barrel of toxic sludge is a bad idea," the duo have started the apocalypse. What follows is a ghoulish domino effect of reanimated corpses, frantic decision-making, and hopelessness as the early moments of a zombie apocalypse play out before our eyes. Suffice to say, it's bad luck that a revivifying chemical was released near a morgue and a cemetery.

Directed by Dan O'Bannon (best known for writing "Alien"), "The Return of the Living Dead" enjoys a breakneck pace that makes the end of the world feel less like a dour inevitability than a rollercoaster to hell. Amongst all the chaos (which includes toxic rain and zombies eating every cop that arrives on the scene), some of the film's finer details are hard to spot on a first viewing. In that spirit, we've compiled an assortment of lesser-known facts about "The Return of the Living Dead." (Warning — there are spoilers below.)

Tobe Hooper was originally supposed to direct

From the advantage of hindsight, it often feels like no one but Dan O'Bannon could've directed "The Return of the Living Dead." The film contains plenty of the writer's penchant for enclosed, siege-like horror (as seen in "Alien" and "Dark Star"). His sardonic wit and pitch-black worldview are also keenly on display. Plus, his contribution to the script of "Dead & Buried," one of the bleakest zombie films ever made, clearly demonstrate his interest in the living dead.

But believe it or not, O'Bannon wasn't the first person in line for the director's chair. That honor fell to horror legend Tobe Hooper, hot off the success of 1982's "Poltergeist." Per Joe Kane's "Night of the Living Dead: Behind the Scenes of the Most Terrifying Zombie Movie Ever," O'Bannon was initially tapped to do a pass on the script. However, when Hooper left the project to direct "Lifeforce" (which, wouldn't you know it, just so happened to be written by O'Bannon), the "Alien" scribe got the gig. All in all, we'd say things shook out for the best. We got Tobe Hooper's "Lifeforce," and we got Dan O'Bannon's "Return of the Living Dead." Talk about kismet.

The film marks a split between the Living Dead franchises

If you're a seasoned genre fan, you may be aware that the family tree of films that spawned from George A. Romero's "Night of the Living Dead" is a bit, uh, confusing. For the uninitiated, strap in.

As detailed in Joe Kane's "Night of the Living Dead: Behind the Scenes of the Most Terrifying Zombie Movie Ever," Romero and co-writer John A. Russo parted ways creatively after the success of the 1968 classic. What followed is a unique wrinkle that horror history has yet to truly replicate itself. See, "Night of the Living Dead" has been in the public domain since its release. This is because the distributor failed to add a copyright indication when it changed the name of the film from "Night of the Flesh Eaters." As a result, both Romero and Russo were free to do what they wanted with the future of the series.

Romero went on to direct five more films with the "of the Dead" suffix. Meanwhile, Russo penned a book that would spawn a series of films with the "Living Dead" suffix. And it's Russo's 1979 novel that would help form the basis of "The Return of the Living Dead."

A notorious illustrator influenced the opening title card

It's possible that you might be headbanging and toe-tapping too hard during the opening credits to pay close attention to the title card. It's one of the greatest opening sequences in film history so we totally understand. But if you take a closer look at the chicken-scratch text — violently etched onto the screen like smeared blood and underlined with claw marks for good measure — you might just realize that there's something familiar about this script.

Indeed, as clarified in the Scream Factory director's commentary, the title's font was based on the style of Ralph Steadman. While his name might not ring any bells, there's a good chance his work has crossed your eyes in the past. The British illustrator is best known for his fruitful artistic collaboration and friendship with gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson. His illustrations feature in the likes of "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas" and contain a surreal, splattered quality that perfectly fits into the visceral vibe of "The Return of the Living Dead."

Tarman's morphing face includes a happy accident

If you're not tapping your toe and pumping your fists during the opening credits of "The Return of the Living Dead," you're doing it wrong. There's so much to admire about the sequence. Where most zombie films build to the reveal of the undead, "The Return of the Living Dead" posits that one absent-minded mistake can immediately open the gates of hell. And as the kick drum pounds and the intermingled sense of dread and delight mounts, we zoom in on the stiff that started it all — the military drum containing (albeit poorly) an infected living corpse.

As the toxin begins to leak, the atmosphere re-pressurizes within the can, and the corpse's leathery skin melts away to reveal the goopy visage of the creature we know and love as Tarman. As the film's DVD commentary explains, the effect was achieved by pointing a heat gun at a head made of wax. And, apparently, the heat gun had an unintended consequence — that striking crack in the glass suggesting something truly nefarious and impatient is waiting to break free. Unplanned though it may be, we're glad the accident was kept in the final cut. If the fates give you a jump scare, who are you to deny them?

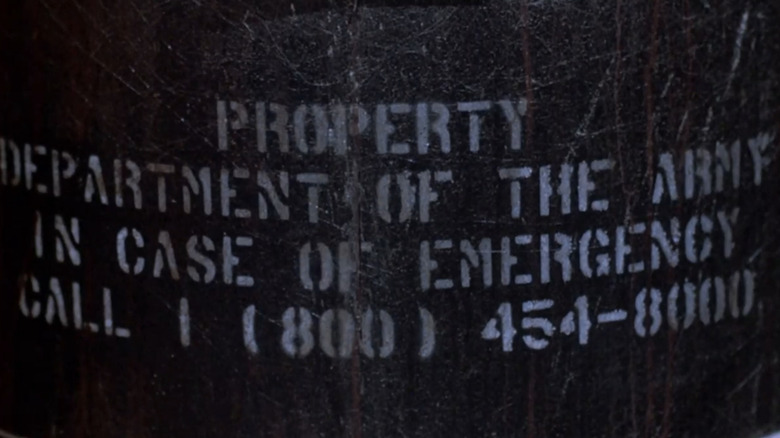

The film contains a sneaky nod to Agent Orange

It's not hard to tell from Dan O'Bannon's whole deal that the man wasn't a huge fan of authority. For example, he was an appreciator of Ron Cobb, an American cartoonist whose visceral counterculture political cartoons caught the filmmaker's attention (the duo would collaborate on both "Dark Star" and "Alien"). But if you really want to know how O'Bannon felt about the establishment (and, more specifically, the Vietnam War), you need look no further than the plot-driving toxin in "The Return of the Living Dead."

In the film, the revivifying substance — originally conceived as a herbicide for marijuana plants — is produced for the military by the Darrow Chemical Company (a fact we learn from Frank's expository monologue to Freddy). This sounds a heck of a lot like the real-life Dow Chemical Company, which manufactured a defoliant for the U.S. military that would come to be known as "Agent Orange." In O'Bannon's film, the zombifying culprit is known as the 2-4-5 trioxin, and in real-life, 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid was used to make Agent Orange. And like its fictional zombifying counterpart, Agent Orange had horrifying side effects that persist to this day.

Frank's not a super reliable narrator

Not long into its runtime, "The Return of the Living Dead" slaps us across the face with a doozy of a revelation: The film "Night of the Living Dead" was based on real-life events. As Frank explains to the wide-eyed Freddy, back in 1969, a chemical spill leaked into the morgue of a Pittsburgh hospital. Then the Army told "the guy who made the movie," aka George A. Romero, that if he told things the way it actually happened, they'd ruin him.

Now, if you're a film freak (or a curious Googler), you'll know that this timeline of events doesn't line up. Romero's film was released in 1968. So how could it be based on an event that took place in 1969? While it's totally possible that Frank just got the date wrong, if you look at the film's screenplay, Frank says that the real event took place in 1966, which would make way more sense. Why the change? Well, maybe it shouldn't be surprising that the same man who got his dates mixed up would kick a barrel full of reanimating toxins. Keep that head empty Frank, that's how we like you.

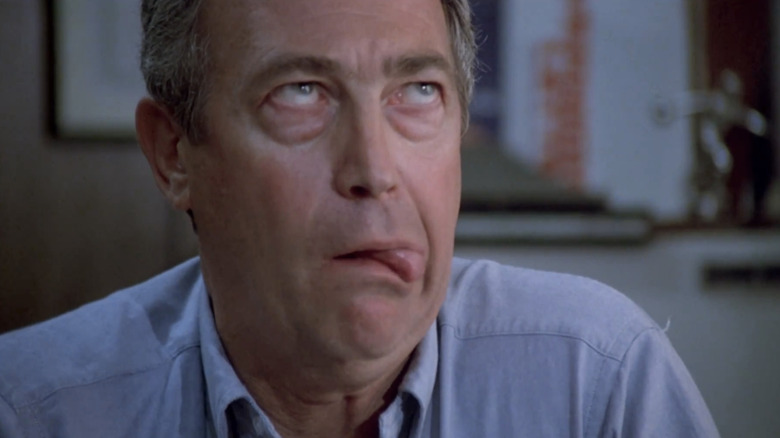

Dan O'Bannon was originally planning to co-star

As Dan O'Bannon relays on the DVD's director's commentary, he originally planned to play the role of Frank. He'd written the part with himself in mind, but supposedly James Karen's audition was just so darn good that he ceded the role to him.

But unlike other behind-the-scenes filmmakers who insert themselves into their own projects, Dan O'Bannon is actually quite the screen presence. In "Dark Star" — the student film he made with John Carpenter that wound up getting a wide release — O'Bannon plays the central roll of Pinback. A misanthrope and a major grump, Pinback is easily one of the highlights of the movie, a disgruntled member of the commercial spaceship whose frustration with his grating crew mates is relatable and genuinely hilarious. Sealing the deal, it's Pinback who gets to wrangle the crew's alien pet, which is, and we cannot stress this enough, a beachball with feet.

All that said, while we totally think O'Bannon could've done a bang-up job, Karen's performance is undeniably great. He's well-meaning and exacerbated, jovial and distraught. Somehow, Karen manages to be over the top without being flippant. He's a joy to watch, even when he's writhing in pain or burning himself to death in the morgue's industrial cremator.

The look of the zombies was inspired by a variety of icky sources

In the films of George A. Romero, the visual look of zombies isn't terribly complicated — dark rings around the eyes and pallid makeup. Done deal. The look of the re-animated dead in "The Return of the Living Dead" is a lot more varied, from revivified piles of goop to bone-dry skeletons to shuffling car-crash victims. As production designer William Stout notes in the special features on the Scream Factory DVD release, the look (well, looks) of the film's zombies originated from a number of different sources of inspiration.

"I started researching what corpses look like," Stout remembers. "I looked at the mummies of Guanajuato, Mexico, whose burial in the region's dry soil did a remarkable job of preserving the corpses." Stout also looked at the designs of the living dead in EC Comics, Tales of the Crypt, and Vault of Horror, particularly the illustrative work of Graham Ingels, Jack Davis, and Bernie Wrightson. According to a set-visit conducted for Fangoria No. 40, the Bog People of Wales were also a visual touchstone. The result is a visual look that feels both credible and playful — snapping jaws, sloughed skin, and taut flesh that's riddled with both veracity and a tongue planted firmly in the cheek (looking at you, skeleton who still inexplicably has eyeballs).

Zombies eating brains was a novel idea

If you ask someone to do their best zombie imitation, chances are they're going to shuffle around with their arms outstretched and gargle "brrrrrrrraaaaaaiiiins." While the former characterization is a tell-tale homage to George A. Romero, the latter belongs entirely to Dan O'Bannon.

"The Return of the Living Dead" is almost single-handedly responsible for forwarding the idea that zombies eat brains. Before that, the ghouls weren't picky — stomachs, cheeks, nothing was off the dinner table. But even though O'Bannon's innovative cranial twist in zombie lore is now accepted as fact, not many folks know why the undead crave the wrinkly goop between our ears.

In "The Return of the Living Dead," we learn (via the tortured torso zombie) that the undead need brains to dull the pain of being dead. Maybe something about the juicy chemicals in our grey matter dulls the stiffness of rigor mortis. Maybe they crave our brains because all that neurological goop is the center of life itself, and as the dead, they want what they can't have. Either way, it's chilling as all get out. Too bad our heroes didn't have helmets.

Some of the extras ate real brains

Given that munching down on goopy human brains is an integral part of "The Return of the Living Dead," at various points, we're treated to grisly scenes of garish ghouls gulping down gratuitous amounts of grey matter. So what were all those undead extras chowing down on? Pink-ish colored gelatin? Delicious gummy candy perhaps?

While some of the extras definitely didn't eat actual brains, according to director Dan O'Bannon's commentary track ... some of them actually did. If they chose to, some extras were encouraged to eat real brains — calf brains to be exact. Their incentive was a cash bonus to sweeten a decidedly not so sweet deal. Supposedly, according to O'Bannon, the director even took a munch out of the brain matter himself to prove to the cast that he would never ask them to do anything he wasn't willing to also do himself. You have to respect it.

Having principal zombie characters was a new twist

These days, we take hero zombies for granted. The idea that some of the living dead get extra special care in the design department, while others fade into the background as forgettable jobbers, is well-established. Look no further than Zack Snyder's "Army of the Dead," which featured among its undead hordes an alpha female ex-showgirl known as the Queen. While the walking dead in George A. Romero's 1968 original were anonymous (which was kind of the point), the idea of "principle zombies" is now more or less the norm. And it's all thanks to "Return of the Living Dead." (With all due respect to Bub — the music-loving, mostly domesticated zombie from Romero's "Day of the Dead," which premiered a mere month before O'Bannon's film — "Return" approaches principal zombies a bit more holistically, which we have to respect).

As production designer William Stout discusses on the Scream Factory DVD extras, the whole point of the film was to do things differently than Romero. As Stout recalls, director Dan O'Bannon put it like this: "You know how there are principal actors? Principle characters in a screenplay? I've written a film where there are principle zombies as well, and I want you to design them so that they stand out and are unique from the other zombies in other films." From Tarman to the torso zombie, the undead characters are arguably as memorable as their living counterparts.

Producers hated that the zombies moved fast

"The Return of the Living Dead" was a zombie game-changer. For example, one of Dan O'Bannon's radical ideas for the re-animated was to have the zombies run rather than shuffle. According to the director's commentary on the Scream Factory release, the producers really, really hated that these were fast zombies, capable of running. Instead, they wished O'Bannon had kept things traditional with the slow, stumbling shuffle that audiences were already familiar with.

"I wanted to surprise the audience," O'Bannon remarked. As production designer William Stout noted on the film's special features, the speed of the zombies was integral to making the ghouls feel genuinely threatening. "If you can't outrun, the mummy you deserve to die" Stout mused. "The Return of the Living Dead" tweaked other core elements of the zombie lore too, including the idea of a bite transmitting "the disease," as well as the idea that beheading a zombie just means you're running from a headless torso and a snapping head.

Tarman has something in common with the Blob

Even if you're in possession of a stomach harder than a diamond, you no doubt suppress a gag every time Tarman lurches onto the screen. Born from the military cannister and barely keeping himself together, his sloughing skin is pitch black and slick from his violent re-entry into the land of the living. So much about Tarman's design elicits a visceral response — his exposed skull, his unblinking eyes, the fact that the only feature with any kind of definition is his hungry, snapping mouth.

Portrayed by Allan Trautman in all the shots where Tarman isn't a puppet, the goopy goober is one of genre cinema's wettest creations. And as Trautman describes in his DVD commentary, a significant ingredient in that slime was methyl cellulose. Derived from wood pulp, this stuff is commonly used as a food thickener, but it's also a favorite of practical effects wizards whenever goop is on the docket. You might have seen methyl cellulose in the 1988 remake of "The Blob," where the thickening substance was used to bulk up quilted silk to create the illusion of an intergalactic snot rocket. It also features in "Ghostbusters" and "Alien," where tactile slime plays an important role in conveying an otherworldly atmosphere. Like his otherworldly cousins, Tarman looks like he's always in the process of melting. And that's thanks to good ol' reliable methyl cellulose.

Freddy's jacket is less explicit in the TV version

When we first meet Freddy, the good-natured punk whose first day on the job at the medical supply warehouse takes an ill-fated turn, he's wearing a tank top. Makes sense. Who knows what kind of heavy lifting his new employer will have him do? He's ready for anything, from loading excelsior to packing up skeletons. Well ... almost anything.

After Freddy and his cheery new boss are infected with the contents of the military drums, their bodies immediately start to fall apart. They're clammy, pallid, and feverish. If your heart stops beating, we'd have to imagine you'd get the chills. Luckily, Freddy's pals have his best interests at heart and outfit him with his letterman jacket to stave off the cold. In a fun twist on an article of clothing typically associated with jocks and preppy kids, the back of Freddy's jacket contains the cheery phrase "F*** You."

Now, how did the filmmakers deal with this rude piece of costuming in the TV edit? Well, according to the DVD commentary, they shot entirely separate scenes where actor Thom Mathews wore an identical jacket with a different, delightfully self-aware phrase on the back: "Television Version." Clever move, filmmakers. Clever move.