The Biggest Unsolved Mysteries In The History Of The Lord Of The Rings' Middle-Earth

Few stones have been left unturned by readers and scholars of J.R.R. Tolkien's legendarium. Over the years, pretty much every aspect of Middle-earth, from its history to its languages to the heroes and villains who inhabit it, has been studied, discussed, and debated, seemingly without end. Organizations such as The Tolkien Society hold lectures and real-life events, while a number of wikis and websites work hard to preserve the lore in the digital realm, and new books are regularly published that explore the inner workings of this vast mythos.

Despite all this, though, Middle-earth still holds a few secrets. No matter how much passion and attention is poured into the study of Tolkien's works, there are some questions that have never been answered by the author himself — not in the text, not in his letters, not in the notes he left behind. Fans can speculate, of course, and many have devised convincing answers along the way, but the simple truth is that there are some things we will never know about the world of "The Lord of the Rings." These are the biggest unsolved mysteries in the history of Middle-earth.

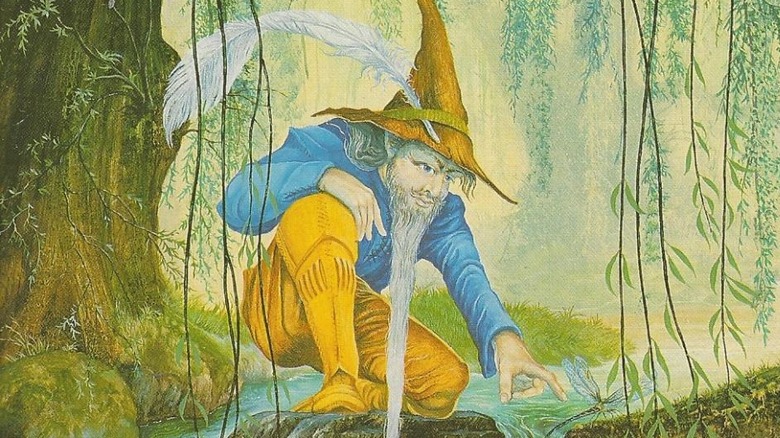

Who is Tom Bombadil?

If there's one question that has truly plagued J.R.R. Tolkien's fans, it must surely be, who — or what — is Tom Bombadil?

In "The Fellowship of the Ring," Tom first appears when he rescues Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin from the vindictive tree known as Old Man Willow. The Hobbits stay a few nights with him, singing and telling stories, and he later aids them in their escape from the evil spirits of the Barrow-downs. After the Hobbits depart for Bree, Tom is never seen again.

While this may seem like little more than a charming side adventure with a whimsical denizen of the Old Forest, Tom, despite his genial nature, appears to be absurdly powerful. He is resistant to the allure of the One Ring and even briefly makes it vanish when Frodo hands it to him. Later on, the Council of Elrond even considers giving it to him for safe-keeping — although they decide against this plan when Gandalf points out that Tom would probably forget it ever existed. Moreover, Tom himself claims to remember "the first raindrop and the first acorn" and that he "knew the dark under the stars when it was fearless," suggesting he is at least as old as Middle-earth itself.

All kinds of theories exist regarding what Tom might be. Nevertheless, when asked about his identity, Tolkien himself once said that, "Even in a mythical Age there must be some enigmas, as there always are." It seems that we were simply never meant to learn the truth about Tom Bombadil.

Where did the Entwives go?

In "The Two Towers," Merry and Pippin encounter Treebeard, an Ent of Fangorn Forest. When the two inquisitive Hobbits ask Treebeard whether there were any Ent offspring, he tells them that, "There have been no Entings [...] for a terrible long count of years. You see, we lost the Entwives." When Pippin asks how they died, Treebeard simply responds that they did not — they were lost, and the Ents could not find them.

The fate of the Entwives isn't certain, but it's hard to imagine anything particularly good happened to them. In J.R.R. Tolkien's Letter 144, the author suggests that they may have been destroyed in the War of the Last Alliance that ended the Second Age, when Sauron employed scorched earth tactics during his retreat across Middle-earth. He concedes that some may have survived and fled eastwards, but points out that even he does not know exactly what happened.

Fascinatingly, in 2017, a Quora user answered a question regarding the Entwives by claiming that Tolkien had annotated their father's map of Middle-earth with the words "Here may be Entwives," near the Sea of Rhûn in the northeastern corner of the map. Playful as he was, Tolkien often insisted that he was as much in the dark about his stories' mysteries as anybody else — but it's still nice to see him throwing his own theories into the mix.

What is the Watcher in the Water?

Middle-earth is filled with many monsters. The wars of the Elder Days and the meddling of Morgoth in the world's natural order gave birth to all kinds of horrific beings, such as Orcs, Dragons, and Balrogs. Some of the creatures lurking within the margins of J.R.R. Tolkien's works, however, are altogether more mysterious — and even more terrifying.

The Watcher in the Water appears in "The Fellowship of the Ring," when it attacks the Fellowship as they attempt to enter Moria. It is a horrific, almost Lovecraftian beast, wielding a terrible strength and many tentacles, and it's only with considerable effort that the heroes escape unscathed. Later, it's revealed that the Watcher had previously killed the dwarf Óin and prevented Balin's doomed expedition from escaping the darkness of Khazad-dûm.

It's hard to say what the Watcher may have been. Gandalf notes after their encounter that it had targeted Frodo specifically, suggesting it may have at least been aware of the One Ring, but little else can be said about it. The only comparable creatures are the "sea-serpents" briefly mentioned in the legendarium's ancillary works; it's possible, too, that the Watcher may have been created by Morgoth during or prior to the First Age and simply migrated to the Sirannon river after his defeat. All we can know for sure is that the peoples of Middle-earth — and especially the dwarves — should be glad that it appears to have vanished sometime after the attack on the Fellowship.

Where did the Blue Wizards go?

The so-called Blue Wizards are by far the most enigmatic members of the Istari, the group of angelic beings who arrive in Middle-earth to guide the free peoples in their war against Sauron. Gandalf is one, of course, while Saruman and Radagast are counted among the others. But while their roles in the history of Middle-earth are more or less clear-cut, many questions remain unanswered about their colorful comrades.

Named as either Alatar and Pallando, Morinehtar and Rómestámo, or Palacendo and Haimenar, the two Blue Wizards arrived in Middle-earth alongside the other Istari during the Third Age. Or they turned up much earlier, during the Second Age. They acted as emissaries to the southern and eastern regions of the world, but soon became corrupted and established "secret cults" and "magic traditions" that endured far beyond the Dark Lord's fall. Or they succeeded in their task, rousing the tribes of Men into rebellion against Sauron and playing a significant role in the greater struggle for freedom. Or maybe it's some combination of the two.

The more optimistic reading — that the Blue Wizards successfully opposed Sauron for thousands of years and indirectly helped secure victory in the War of the Ring — is based on J.R.R. Tolkien's later writings, so perhaps that version is closer to the truth. Like much that happens beyond the edges of Middle-earth's map, however, it's impossible to say for sure.

Are there more than five Istari?

Readers of "The Silmarillion" and "Unfinished Tales" will tell you that the Istari, or Wizards, are in fact Maiar, a race of beings who dwell in the Blessed Realm of Aman and serve the god-like Valar. On the surface, it seems like the Valar send five of the Maiar to Middle-earth during the war against Sauron: in their guises as Istari, they are known as Gandalf, Saruman, Radagast, and whatever you want to call the Blue Wizards.

In "Unfinished Tales," however, J.R.R. Tolkien suggests that more of their kind may have roamed Middle-earth. The author writes that, "Of [the Istari] the number is unknown; but of those that came to the North of Middle-earth, [...] the chiefs were five."

Apparently, most of the Istari were sent to where the action was taking place — that is, where the last of the Dúnedain (most importantly, Aragorn) and the greatest of the elves lived. But this passage suggests that more of the Maiar may have been sent to Middle-earth as Wizards. Who are they? What tasks were they given? Did they succeed or fall into darkness? Nobody knows, because Tolkien never mentioned them again.

What are the stone-giants?

Giants play a prominent role in the fantasy genre. Authors from Roald Dahl to George R.R. Martin to Jonathan Swift have played with the idea of mankind encountering huge, lumbering monsters, and for a while at least, J.R.R. Tolkien had also found a place for giants in his legendarium.

The most famous of Tolkien's giants appear in "The Hobbit," when Bilbo and Thorin's company witness "stone-giants" hurling gigantic rocks at one another as they pass through the Misty Mountains. In earlier versions of his world, Tolkien included giants as servants of "Melko," the Dark Lord character who later became Melkor (and then Morgoth.) Later, Tolkien made a distinction between "wood-giants" and "mountainous-giants." He also suggested, at one point, that they may have held some relation to the Ents.

Eventually, though, Tolkien seems to have given up on the concept of giants altogether, promptly jettisoning them from Middle-earth. The problem here, of course, is that they already exist in the pages of "The Hobbit" — so what are Bilbo's stone-giants supposed to be? Giant versions of Men? Nature spirits? Wayward servants of evil, like Dragons and Trolls? Or are they the product of an overexcited Hobbit's imagination? Your guess is as good as ours.

Where do Orcs come from?

No Middle-earth monster has made such an impression on the fantasy zeitgeist as the Orc. Although the word dates back as far as 800 A.D. (per Britannica), the wild success of "The Lord of the Rings" spurred a wave of Orcish imitators in the fantasy genre.

While the real-world legacy of Middle-earth's Orcs is no doubt impressive, their in-universe origins remain something of a curiosity. J.R.R. Tolkien never fully decided on their definitive history: His earliest work, "The Book of Lost Tales," claims that Melko birthed the Orcs out of the earth — an idea that endured in his immediate revisions, which suggested that the Dark Lord crafted them out of stone.

A more famous origin for the Orcs emerged in the 1950s, when Tolkien wrote that many of the elves who fled the Vala Oromë after their awakening were captured by the Dark Lord (now named Melkor) and twisted into the first Orcs. After that, he suggested that Orcs may have been corrupted Men instead, and also toyed with the idea that they had both Elvish and Mannish origins.

These contradicting ideas caused countless headaches for Tolkien, his son Christopher, and fans of the legendarium, as each conception has various repercussions in terms of free will, immortality, and chronology. His last writings on the subject state that the Eldar thought Melkor bred Orcs from "various kinds of Men." And that's about as close as we're ever going to get to a final word on the issue.

What is Radagast's fate?

More peculiar than Gandalf or Saruman and yet not quite as puzzling as the Blue Wizards, Radagast the Brown plays only a small role in the events of "The Lord of the Rings." For a while, he acts as Saruman's unwitting spy, using his birds to hunt for the One Ring and subsequently luring Gandalf to Orthanc. Radagast redeems himself soon after, though, by sending the Eagle-lord Gwaihir to rescue his ally from Saruman's grasp.

After that, Radagast is never heard from again. The Elves search for him after the Council of Elrond, but when they arrive at his home, Rhosgobel, they find that he's gone missing. So what happened? Was he destroyed by Saruman or the evil that lurked in Mirkwood, near which he lived? Did he give up on the War of the Ring and travel east, preferring to live among the birds and the beasts of Middle-earth? Did he succeed in his appointed task, or fail?

Surprise, surprise: it's a matter of some debate. J.R.R. Tolkien suggested at various points that Gandalf was the only member of the Istari to remain faithful and that only Gandalf returned to Valinor after Sauron's fall. He also once wrote that, "[Gandalf] differed from Radagast and Saruman in that he never turned aside from his appointed mission," speculating that Radagast became "neglectful and easygoing," as he preferred the company of animals to that of Elves or Men. This shines at least a little light on Radagast's final fate — even if it's not quite a definitive answer.

Who are the Nazgûl?

You know the Nazgûl: They're the horrific, black-hooded captains of Sauron who hunt the Hobbits in "The Fellowship of the Ring" and take the war to Gondor in "The Return of the King." But do you really know them?

The Nazgûl go by many names — Ringwraiths, Black Riders, the Nine — but their actual identities are something of a question mark. We know for certain that they were once lords of Men, and that Sauron gifted each of them a Ring of Power during the Second Age. They used these Rings to acquire unimaginable wealth and power, prolonging their lives indefinitely but slowly, over time, fading into wraiths, gradually falling under the domination of the One Ring.

Only one of the Nazgûl is ever named by J.R.R. Tolkien: Khamûl, the second-in-command to the Witch-King. In "The Silmarillion," Tolkien mentions that Khamûl was a king of the Easterlings. He goes on to write that three of the Nine were lords of Númenor, and it's entirely possible (although unconfirmed) that one of these later became the Witch-King of Angmar. That leaves five remaining Ringwraiths, but since Men were spread all across Middle-earth during the Second Age, they could have originated from pretty much anywhere. Sadly, their true names, their homes, and the very human fears that likely drove them into darkness will never really be revealed. Still, the whole point of the Nazgûl is their embodiment of the monstrous consequences of pride and desire. Perhaps it's better that they remain mysterious.

Where did Maglor go?

Towards the end of the Years of the Trees, the Dark Lord Morgoth stole the Silmarils, fabled jewels crafted by the Elf-lord Fëanor. Enraged, Fëanor and his seven sons proclaimed a sacred oath: that they would wage war on anybody who kept the Silmarils from them, no matter who they may be.

Hundreds of years later, Morgoth was assailed by the Host of the Valar, overthrown, and cast into the Void. By this point, most of Fëanor's sons had been killed, with only Maedhros and Maglor left to carry out their father's oath. When Eönwë, leader of the Host of the Valar, took possession of the Silmarils, Maglor and Maedhros demanded he turn them over. He refused, so they infiltrated his camp and stole them back. However, the many evil deeds they'd committed caused the jewels to burn in the hands of the thieves. Driven to despair, Maedhros cast both himself and his Silmaril into a fissure in the earth, while Maglor hurled his into the sea.

Here's the interesting part, though: Unlike his brother, Maglor didn't die, and his fate became unknown. "The Silmarillion" states that he still wanders the shores of Middle-earth, singing songs of tragedy and regret, unable (or unwilling) to ever return to Valinor. This poses a few questions: To where did he journey? Did he ever again play a role in the history of Middle-earth? And is he supposed to still exist today, in our time, long after the end of the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Ages of the world?

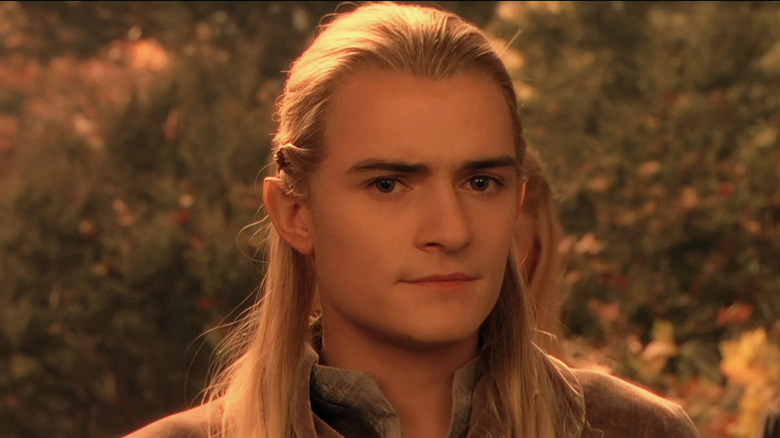

Who was Legolas' mother?

Legolas might well be the most famous Elf in all of J.R.R. Tolkien's works. A member of the Fellowship of the Ring, companion to Aragorn and Gimli, and all-around badass throughout the War of the Ring, Legolas is also unique among the Fellowship in that — Wizards notwithstanding — his exact parentage has never been fully explained.

We know who Legolas' father is, of course: Thranduil, king of the Silvan Elves of the Woodland Realm. Thranduil doesn't appear in "The Lord of the Rings," but he does play a vital role in "The Hobbit," in which he first captures and then wages war against Thorin's company of dwarves. But nobody has any idea who Legolas' mother could be.

For some reason, Tolkien never expanded on Legolas' early life beyond what little is mentioned in "The Lord of the Rings." His age, his adventures earlier in the Third Age, and indeed his mother's name are more or less total blanks. There certainly is no queen of the Woodland Realm in "The Hobbit," so we can probably assume that, whoever Legolas' mother is, she likely died long before Bilbo's quest began. For its part, Peter Jackson's "The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies" attempted to bridge this particular gap, explaining that the Elf's mother was killed in battle at the Orcish fortress of Mount Gundabad. Whether fans are willing to accept that as anywhere near canonical, however, is another matter entirely.

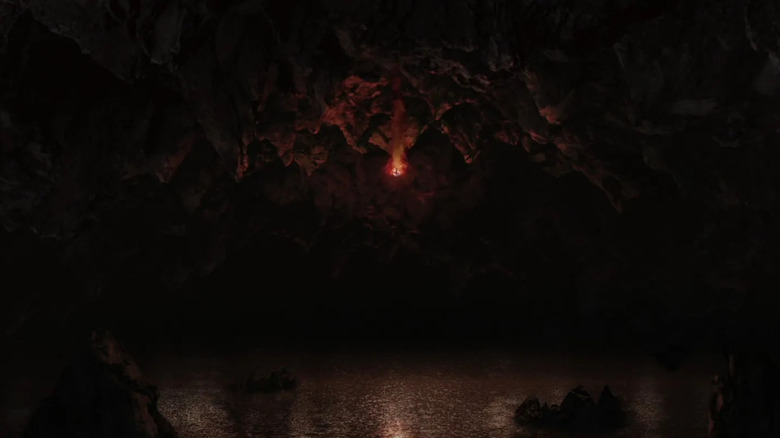

What are the Nameless Things?

You'd be forgiven for believing that the Watcher in the Water, the Balrogs, or Shelob might be the creepiest creatures Middle-earth has to offer — but you'd be wrong.

When Gandalf reunites with Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli during "The Two Towers," he tells them about his battle with Durin's Bane after the Fellowship's journey through Moria. During their fight, the two foes wound up traversing the deepest tunnels beneath the lowest reaches of Khazad-dûm. There, he witnessed something truly horrific. "Far, far below the deepest delving of the Dwarves," Gandalf says, "the world is gnawed by nameless things. Even Sauron knows them not. They are older than he. Now I have walked there, but I will bring no report to darken the light of day."

Known only to fans as the "Nameless Things," these beings have unsettled the minds of J.R.R. Tolkien readers for decades. The notion that they are older than Sauron is particularly noteworthy, since Sauron — as one of the Maiar — was around for the creation of the universe itself, and that even Gandalf refuses to speak about them suggests that they are foul beyond all comprehension. It's possible, of course, that they bear some relation to the Watcher, since they share the Misty Mountains as a home; it's also possible that they're much, much worse.

What is Beorn?

In "The Hobbit," Bilbo, Thorin, Gandalf and the other Dwarves stay for a while at the house of Beorn, a hermit who lives between Mirkwood and the Misty Mountains. It quickly becomes clear that Beorn is a skin-changer: a man who is able to take the shape of a bear. Indeed, Beorn transforms into his bear-form during the Battle of the Five Armies, when he rescues Thorin from the Goblin armies and destroys their leader, Bolg.

Shape-shifters frequently appear throughout European folklore, and even J.R.R. Tolkien played with the concept on more than one occasion: In "The Silmarillion," Lúthien transforms herself and Beren into a vampire-bat and a werewolf, while Sauron also has taken the form of a serpent and a wolf. But the origins of Beorn's kind are wholly mystifying.

He's certainly not unique, as both "The Hobbit" and "The Lord of the Rings" mention the "Beornings," descendants and followers of Beorn who are also able to change into bears. Little is said of his ancestors, however, aside from Gandalf's suspicions that Beorn's people may have inhabited the Misty Mountains before the Orcs moved in. They're clearly related to Men in some way, and one Tolkien scholar described Beorn as "a bit of a magician," but no full explanation is ever given to the source of these powers. Were Beorn's kind sorcerers or followers of Morgoth in the Elder Days? Or were they the progeny of some Maia who came to Middle-earth? Nobody knows.

What happens to the souls of Men after they die?

Death is strange in the world of J.R.R. Tolkien. Here's how it works: Men and Elves are each made of fëar and hröar — essentially, souls and bodies. When an Elf's hröa is killed in Middle-earth, their fëa can choose to journey to the Halls of Mandos, a purgatory-like region in the western continent of Aman, where it is judged by Mandos himself. After a time spent waiting in the Halls — the length of which is dependent on the Elf's deeds or misdeeds during life — the fëa is rehoused in a new body and allowed to live in Valinor until the very end of Arda itself.

Men suffer a much different fate, however. After death, a Man's fëa leaves the hröa and also journeys to the Halls of Mandos. From there, however, it departs Arda for good. Only three beings know the final fate of the souls of Men: Manwë, chief of the Valar; Mandos; and Eru Ilúvatar, the creator of the universe. It has been suggested that the fëar of Men will one day participate in the Second Music of the Ainur, in which the world will be remade, but to what end or greater purpose is unknown.

Neither the inhabitants of Arda nor readers of Tolkien's works will ever understand the true destination and purpose of the fëar of Men. Considering Tolkien was a devout Catholic, it's almost certain that this is the way he intended it to be.