Everything Philadelphia Doesn't Tell You About The True Story

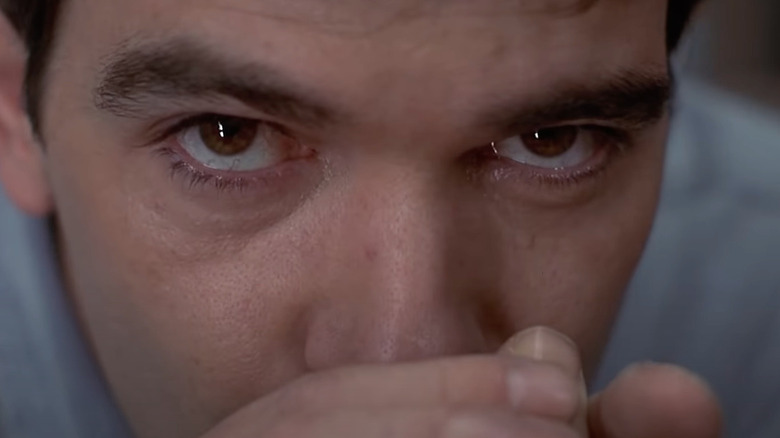

When "Philadelphia” was released in 1993, it was the first major studio film to address the AIDS crisis. Director Jonathan Demme decided he wanted to make a film about the AIDS crisis, right off the critical and box-office success of "The Silence of the Lambs." Screenwriter Ron Nyswaner told The Hollywood Reporter that "there was a certain point at which there was no opposition because people weren't going to tell the director of 'The Silence of the Lambs' what he could and couldn't do." The result was a film with unprecedented honesty about the disease and its effects. Most importantly, the film focuses on the humanity at the center of the crisis.

Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, AIDS-related discrimination was rampant enough that the films' producers, director, and writers didn't have to go far to find inspiration. "In those days, if you lived in New York City as I did, and if you worked in the movie business as I did, you were surrounded by people who were facing HIV and AIDS," said Nyswaner (via THR). However, while you won't see the words "based on a true story" at the beginning of the film, there were a few cases that specifically inspired "Philadelphia." Here's everything the movie doesn't tell you about the true story.

Philadelphia is loosely based on a true story

The primary inspiration for the movie came from the case of Geoffrey Bowers. Shortly after the film's release, the Los Angeles Times reported that, in 1988, producer Scott Rudin had entered into an agreement with Bowers' family regarding the story. Rudin's project never got off the ground, and he wasn't involved in the production of "Philadelphia." However, Rudin worked on a similar concept prior to Jonathan Demme starting his own work on the film. Bowers' estate filed a lawsuit after the film was released, the conclusion of which included TriStar Pictures acknowledging that the film was "inspired in part" by Bowers' own case of wrongful termination.

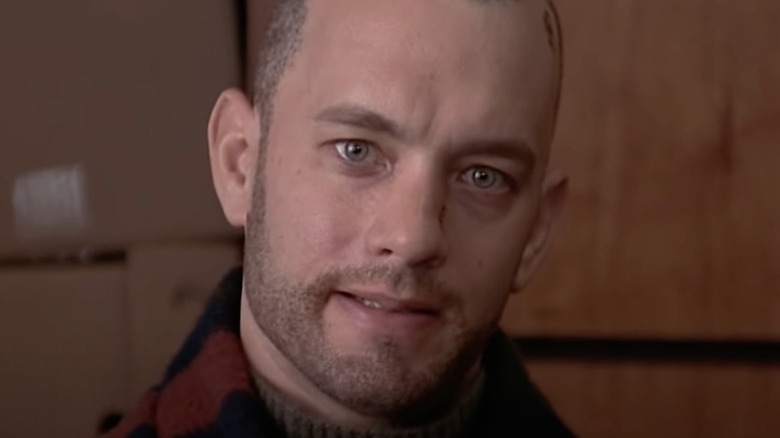

There are many distinct parallels between the story of Geoffrey Bowers and "Philadelphia." Bowers, who died in 1987, was fired from his position at the law firm Baker McKenzie "after he developed Kaposi's sarcoma lesions on his face," just like Tom Hanks' character Andrew Beckett. And, as depicted in one of the most moving moments in the film, Bowers removed his shirt to show lesions on his chest due to the fact that the lesions on his face were no longer visible.

The story was also inspired by another lawyer, Clarence Cain

Tom Stoddard, an activist and consultant on "Philadelphia," told the Los Angeles Times that, in addition to the Bowers case, the filmmaking team drew inspiration from the discrimination suit filed by Clarence Cain. Cain, a lawyer, was fired from Hyatt Legal Services Corp. after disclosing his AIDS diagnosis to his supervisor. According to The Washington Post, Cain was fired despite having just been given a raise.

Unlike Bowers, who lived in New York City, Cain did in fact live and work in Philadelphia. Cain, who was Black, was the first in his family to attend college. Losing his job had enormous financial ramifications. According to The New York Times, Cain declared bankruptcy and, despite having been a financial provider for them, was concerned his family would have to pay for his cremation. Cain died on June 7, 1990.

In Bowers' case, the financial compensation was much smaller

At the conclusion of "Philadelphia," the jury awards Andrew Beckett $143,000 in back pay and loss of benefits, $100,000 for mental anguish and humiliation, and an astonishing $4,782,000 in punitive damages. With a total award of nearly five million dollars, the film portrayed a very optimistic outcome.

In reality, the awards were not nearly as significant. In the case of Clarence Cain—who had helped support his large family that included his mother, nine siblings, and several nieces and nephews— was awarded just $107,888 in damages and $50,000 in punitive damages (via The Washington Post). For Geoffrey Bowers, the award was back pay and $500,000 in damages. While these amounts are just a fraction of the amounts portrayed in "Philadelphia," Bowers' award was significant in that it was the largest award ever ordered by the New York Division of Human Rights, according to AP.

Bowers died before the case was resolved

In "Philadelphia," by the time Joe Miller (Denzel Washington) wins the lawsuit, Andrew Beckett is in the hospital, spending his final day with his family. Miller drops by to celebrate with Beckett. Once his friends and family leave, Miller tells his partner "I'm ready." He dies that night.

Geoffrey Bowers never got to see the end of his case. According to The New York Times, Bowers died just nine months after he filed his lawsuit, 11 months after he was fired, while the case went on for over seven years. However, it was important to Bowers that he continued fighting despite his ill health. A friend told the Times that the case "gave him a sense of belonging, a sense of worth, the fact he could continue his job even though he had this deadly disease." While Bowers died before the case was settled, and never saw any of the financial rewards, he also knew that he was fighting for a cause he believed in.

The real-life law firms did not manufacture missing paperwork

For Andrew Beckett in "Philadelphia," the firm asserts that he was fired due to negligence with his work, citing an incident of a missing report— a missing report that the firm hid in order to create a fireable offense on Beckett's record.

There is no mention of a missing report in either Bowers or Cain's cases. Baker McKenzie accused Bowers of failing to "adequately prepare" for a case and "exercising poor judgment." However, two months prior to the firing, Bowers had a positive annual performance evaluation. Additionally, the firm didn't follow their usual firing procedures. Overall, the records showed that Bowers was a productive lawyer and his dismissal would leave a significant gap in coverage (via The New York Times).

Cain's record is even more positive. The defense tried to portray Cain as incompetent, but they were not successful. Cain's friend and lawyer Richard Silverburg quit his job at Hyatt in protest of Cain's firing. Several years after the case, Joel Hyatt told the Washington Post that Cain "was an ambitious, talented person trying to succeed." Hyatt continued, "We identified that and put him on a specially designed fast track." Hyatt freely admitted that firing Cain was a mistake.

Denzel Washington's was written for the purpose of the film

In the real-life cases of Bower and Cain, both men were represented by friends. These friends cared deeply about them and about pursuing justice over the wrongful terminations. Bowers was represented by his friends Robert Balsam and Daniel Felber, who by all accounts were supportive from the start. Cain was represented by his friend Richard Silverburg, who had quit in solidarity after Cain was fired.

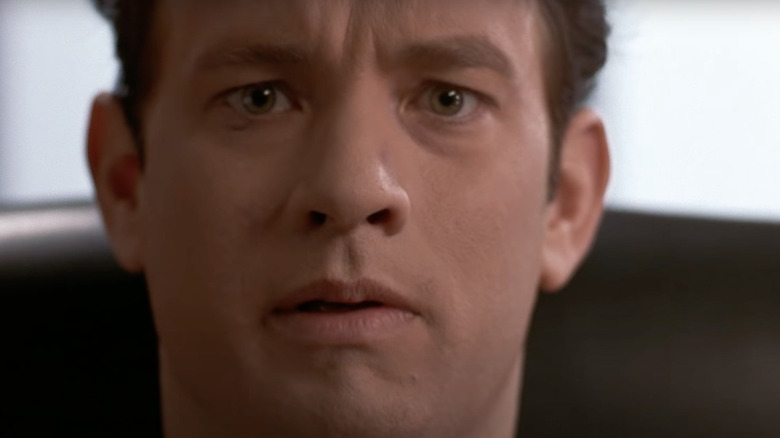

It was very important to director Jonathan Demme that "Philadelphia" would appeal "to the malls" (via Independent). In other words, they wanted people who weren't familiar with HIV to identify with the film. Joe Miller, Denzel Washington's character, was created as a sort of audience surrogate. At the beginning of the film, Miller is deeply homophobic, and even initially refuses Beckett's case due to his discomfort with Beckett's sexuality.

The filmmakers knew that many people watching the film would identify with Miller more than Beckett. "We said from early on we're not looking for an audience that knows somebody with AIDS — the audience has a lot more in common with Denzel's character than Tom's character," producer Edward Saxon told Smithsonian Magazine. "So much of the crisis was about people being homophobic." As Miller gets to know his client Andrew Beckett better, and sees first hand the suffering as well as Beckett's humanity, Miller's homophobia recedes, giving the audience a learning experience as well.

Bowers' partner also died from HIV/AIDS

In "Philadelphia," Andrew Beckett's long-term partner, Miguel Alvarez (Antonio Banderas), has not contracted HIV despite being exposed to it. Alvarez is a very supportive partner who takes careful care of Beckett, ensuring that he receives his medicine and keeping careful records of his hospital visits. Unfortunately, Geoffrey Bowers' partner, with whom he lived in New York City, did in fact acquire HIV, and died about a year after Bowers (via The New York Times).

While the representation of a gay relationship in a big, mainstream movie like "Philadelphia" was rare at the time, some critics of the film found that the relationship was overly platonic rather than sexual. Demme had actually shot a scene of Hanks and Banderas cuddling in bed. But, because Demme felt it didn't work dramatically, the scene didn't make the final cut (via Independent). Tom Hanks later recalled that they were very careful about the representation of Andrew Beckett's relationship in the film, and did not want to sensationalize it. Hanks told the Independent that "as an actor I would want to avoid the artificial attention [a make-out scene] would have gotten."

Both Bowers and Cain died in poverty

One aspect of the true story not shown in "Philadelphia" is how extreme the ramifications of these wrongful firings were. While financial troubles are not shown for Beckett in the film, both Bowers and Cain died in poverty.

After he was fired by Baker McKenzie, Bowers had to rely on the financial support of his friends and partner, The New York Times reported. Despite his loss of benefits and mounting medical bills, Bowers died before he received any financial awards from the case.

Cain, who with a salary of $44,000 per year was already paid significantly less than Bowers' $81,000, experienced even more dire financial straits. The Washington Post reported that after losing his job, he was forced to move out of his condo into a small, roach-infested apartment, and eventually back to a low-rent project to live with his mother, grandmother, sister, and nieces and nephews. Before his death, Cain told The Philadelphia Inquirer that "the ultimate indignity is not being able to take care of yourself, knowing that you may have to borrow money from your parents to be cremated." The experiences of these two men make an even stronger case for the message of "Philadelphia"– that no one should be discriminated against for their sexual orientation or medical condition.

Bowers and Cain's families were very involved in their lives

One of the most touching aspects of "Philadelphia" is the love, support, and acceptance Andrew Beckett receives from his family. At a family event, he shares the news that he has filed a lawsuit, and his family gives him an outpouring of support. "I don't believe there is anything that anyone could say that would make us feel anything but incredibly proud of you," says his father. "I didn't raise my kids to sit in the back of the bus," says his mother.

This statement from Beckett's mother in the film comes directly from Bowers' family. The Los Angeles Times reported that in the lawsuit the Bowers' estate filed against TriStar pictures, Bowers' brother Charles is quoted saying, "My mother would never be ashamed to see one of her kids refuse to sit in the back of the bus." After his death, and after the conclusion of the case, Bowers' family continued to fight against HIV discrimination.

Clarence Cain was fiercely loved by his mother and nine siblings. According to The Washington Post, after Cain moved back in with his mother, Lillie Mae, she "would rock him in her arms, murmuring, 'Pray, son," and his nephew running to attend to his Uncle's every need. Both Bowers and Cain's families were wonderful examples of acceptance and support during their lawsuits.