That's What's Up: Comics That Predicted The Future

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: Which "possible future" comics got their predictions about the present day scarily right? — @jendatweets

Superhero storytelling has been pretty heavily concerned with the future since the beginning, and that makes a lot of sense. It is, after all, a genre that was defined by an alien crash-landing in Kansas after escaping the apocalyptic destruction of his home planet and growing up to become the Man of Tomorrow. With that kind of direct connection to sci-fi, worrying about the world that's coming is second nature.

The thing is, comics treat that worry just a little bit differently than everything else.

Days of Future Past

Superhero stories have gone into horrible futures so much that at this point, it's just straight-up expected from the moment that you embark on a career of crimefighting that you're eventually going to run into a version of yourself with a white streak in their hair, an eyepatch, and a robot arm who's showing up to warn you about how everything is going to go bad sometime in the next two weeks. Admittedly, it's not exactly a new idea, and it's certainly not unique to comics—just ask Charles Dickens about that last spirit who shows up to pester Ebenezer Scrooge—but it's such a prominent trope of the genre that it's almost synonymous with how superheroes work.

If I had to pin down a reason, I'd guess it has a lot to do with the way mainstream superhero comics have been presented over the years, as stories that are never actually supposed to end. They're ongoing sequential narratives, and while you can see similarities in other genres—like soap operas and pro wrestling, two other 20th century innovations that are often regarded as the lowest of low-brow storytelling—nothing else really works like they do.

For decades superhero stories were these distinct units of storytelling where we got to see the good guys winning over and over again. That's not exactly unexpected, since that's how stories tend to work, but superheroes were sliding neatly into the victory every time a new issue hit the stands, and for a popular character like Superman, that could be four or five times a month. When you see the good guys winning that often, you're going to wind up asking the question of what happens if they lose.

The king of bad futures

It's not an approach that's really sustainable for long-term storytelling—if Batman loses, we don't get any more Batman stories, and that's something that might cause entire economies to crumble—but it is something that can break the formula just enough to make everything else seem more important. It shows the stakes, and underlines the idea that if these heroes do fail, then we're going to end up with a world that's at least as bad as one that doesn't even have superheroes at all.

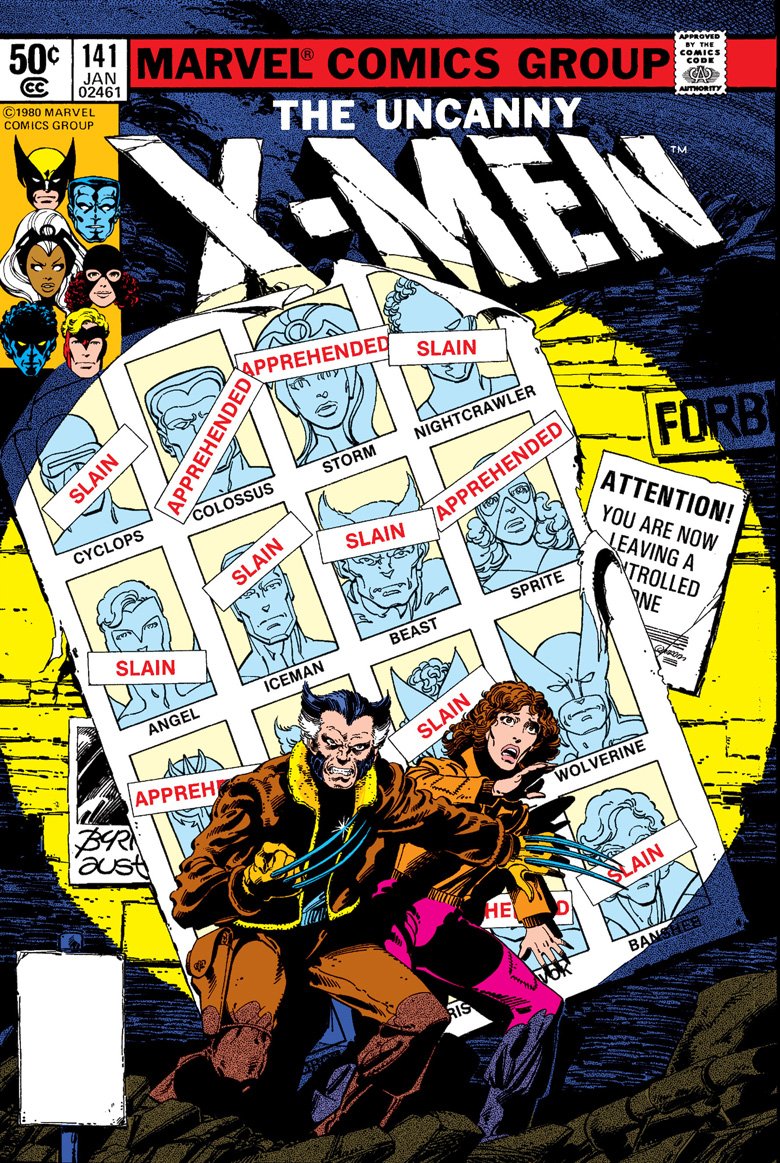

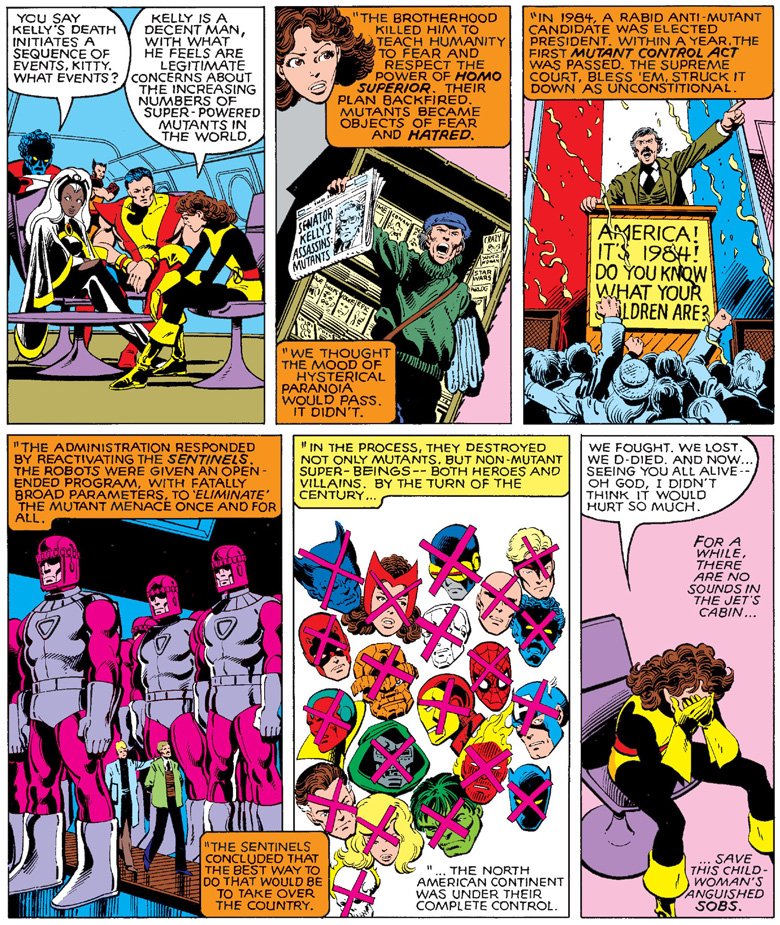

As a result, most of them are told as cautionary tales. This is your standard disclosure that I've written the X-Men for Marvel before, but "Days of Future Past," from Uncanny X-Men #141 and 142, is unquestionably the most famous Bad Future ever printed, showing an America full of concentration camps watched over by giant purple robots made of racism. It's a sci-fi twist on the very real fears that start with politicians riling up hatred and demonizing human beings for being different, which works because X-Men at its core is already a sci-fi twist on those same ideas. "Days of Future Past" just takes it to its logical extreme and shows what happens if nobody's there to stop it.

That said, there's a difference between stories like that and the ones that are actually permanently set in the future. Books like Legion of Super-Heroes, Marvel's 2099 imprint, or even something as weird as Camelot 3000—you know, the book about how King Arthur comes back in the year 3000 and fights off an alien invasion by using Excalibur to slice an atom in half?—have to work with another approach.

They're the ones tasked with presenting the concerns and ideas of the present with a sci-fi coat of paint, and all of them get something a little bit right. The 2099 books were rooted in that early '90s cyberpunk fear of mega-corporations taking over the world and people getting a little too into fetishizing the Punisher, and Legion is, at heart, a distant future that shows us that teens will always be jerks to each other. But if we're looking at one single title set in the future that managed to predict the most, even under a superheroic surface? That one's easy.

Jack Kirby's OMAC: The One Man Army Corps

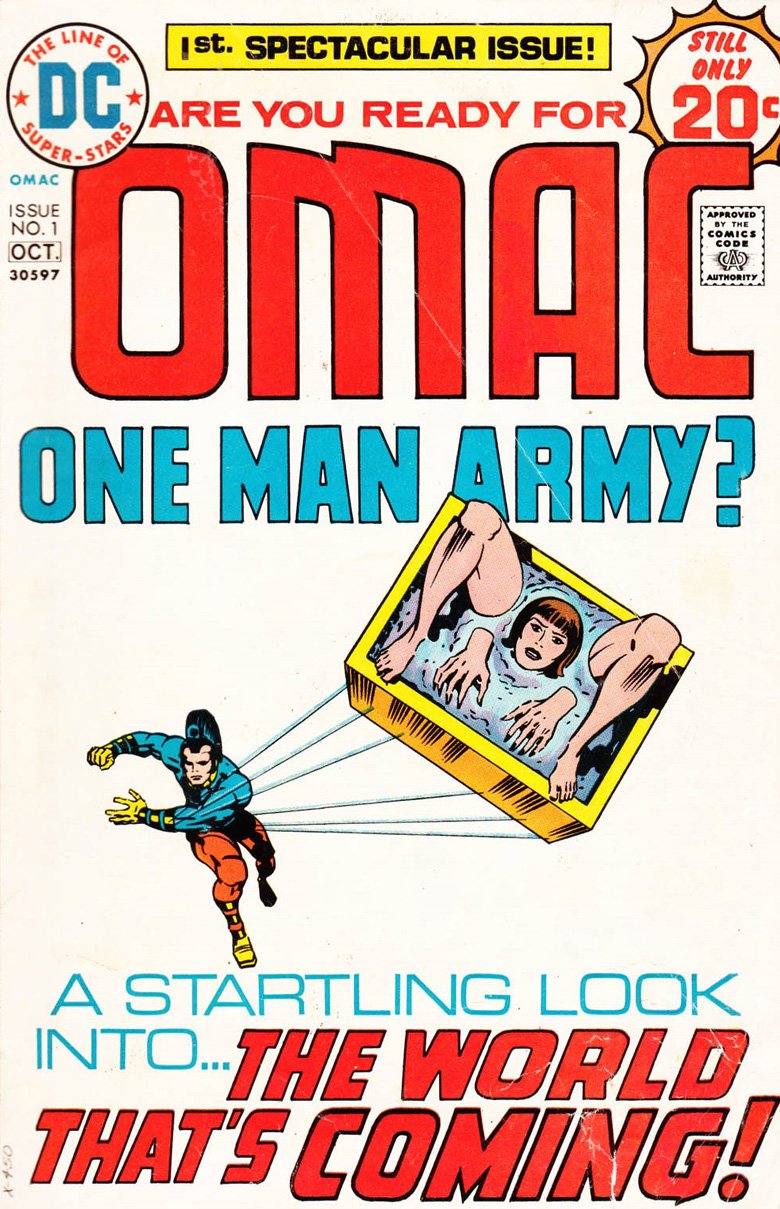

It's OMAC: The One Man Army Corps.

As much as I love his entire catalogue now, OMAC was the first Jack Kirby comic that I really loved, and there's a lot to love about it. Even for a creator whose work was defined by planet-eating space gods and a "Madbomb" that could destroy the world, the action of OMAC is ridiculously over the top, with its title character crashing through armies of opponents while bystanders shout things like "He did it! The One Man Army broke in here against impossible odds!"

Even that first cover is a sign of just how buck wild this book is. Kirby's 70s-era covers are always a little heavy on the text, promising epics for our times and dreaded fear machines, but just imagine encountering that thing on a newsstand right next to the latest issue of Superman: a stark white background, text that's questioning whether you're even ready to read this comic, and, weirdest of all, a tiny figure of the main character hurling what appears to be a dismembered woman directly at the reader. Don't worry, she's actually a robot, but at first glance, you definitely don't know that. It makes a hell of an impression, and if comics that assault your senses and make you wonder what's actually going on are your jam, then OMAC is definitely where it's at.

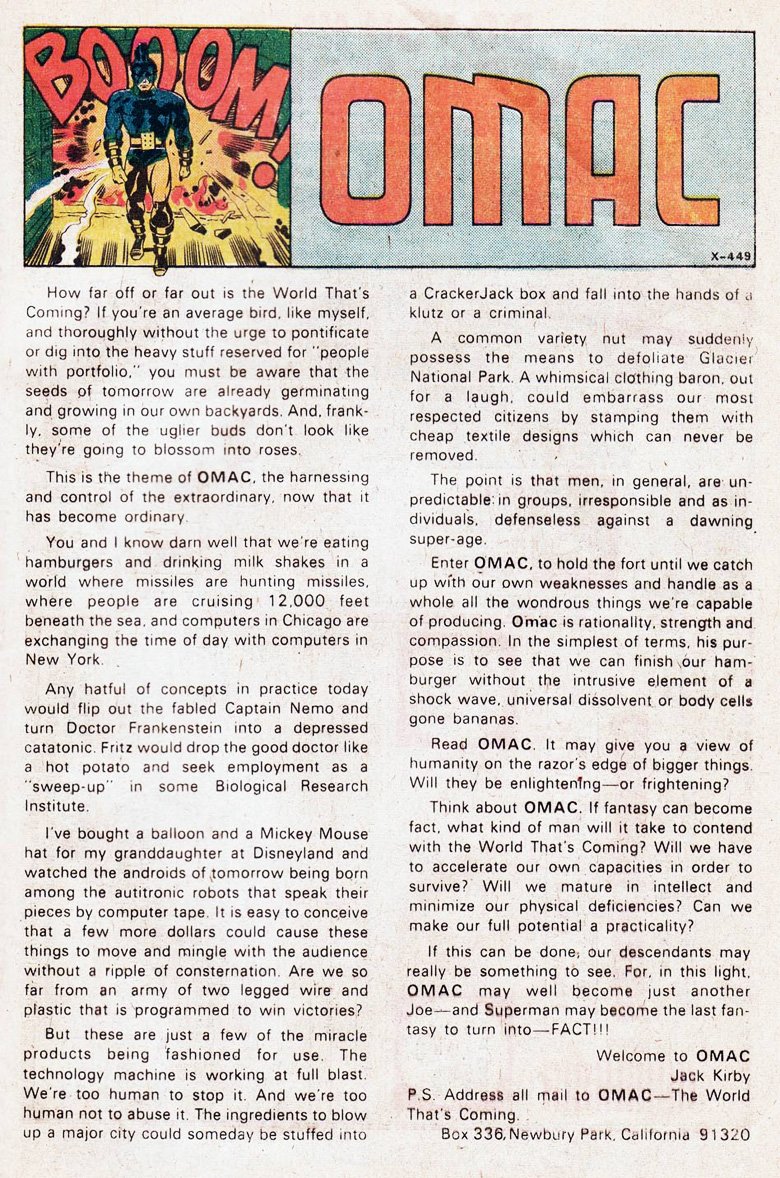

The prophetic text piece from OMAC #1

But here's the thing: It's also one of the smartest comics Kirby ever made.

Like a lot of media from the Cold War, OMAC is directly informed by fears of nuclear annihilation. The core premise of the book is that full-scale war has become so dangerous that even using an army could lead to armageddon, leading the international Global Peace Agency to create an operative who could be as effective as an entire military force, but small enough to operate outside any nation's control: a One Man Army Corps. But rather than just stopping at the fear that was so prevalent around him, Kirby—a creator who always kept up with technology in an effort to mine new ideas for stories—took the next step of trying to figure out what kind of future we'd see in the World That's Coming.

As much as I like the action on the page, the one thing that comes to mind when I think of OMAC is the text piece at the end of the first issue, where Kirby lays it all out for his readers. In two columns of text, he talks about devastating weapons small enough to fit into suitcases, a "common variety nut" possessing the means to defoliate Glacier National Park, and the perils of drone warfare. If that wasn't enough, he also makes a passing mention of networked computers exchanging information across long distances, like, say, the thing you're using to read this right now. And he was talking about that stuff in 1974.

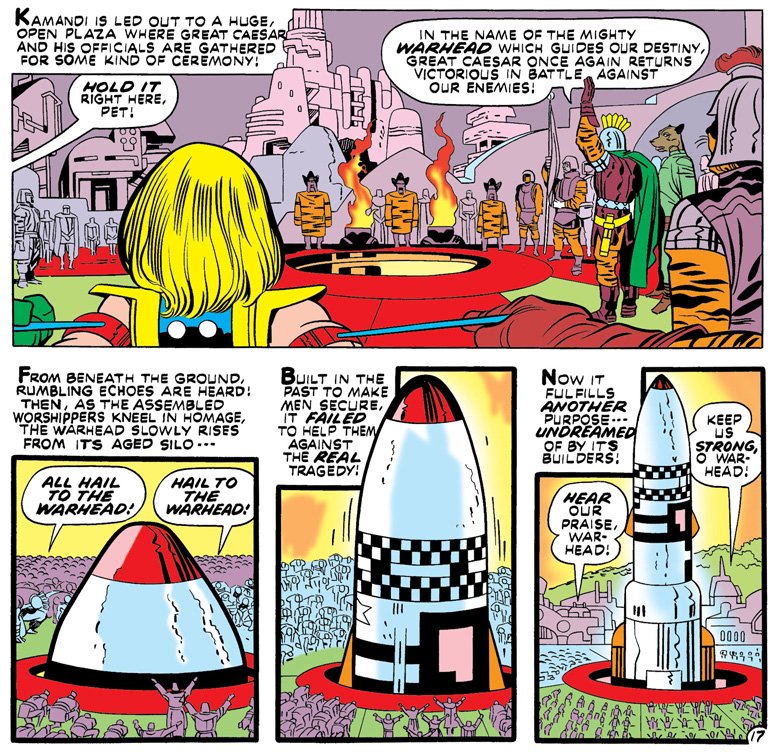

The Destruct Room

There's an issue where OMAC fights a guy who's holding the world's water supply for ransom, too, but it's not just the big ideas that make OMAC seem so prescient. When you look back at OMAC's vision of The World That's Coming from The World That Actually Came, it's the specifics that seem so prophetic.

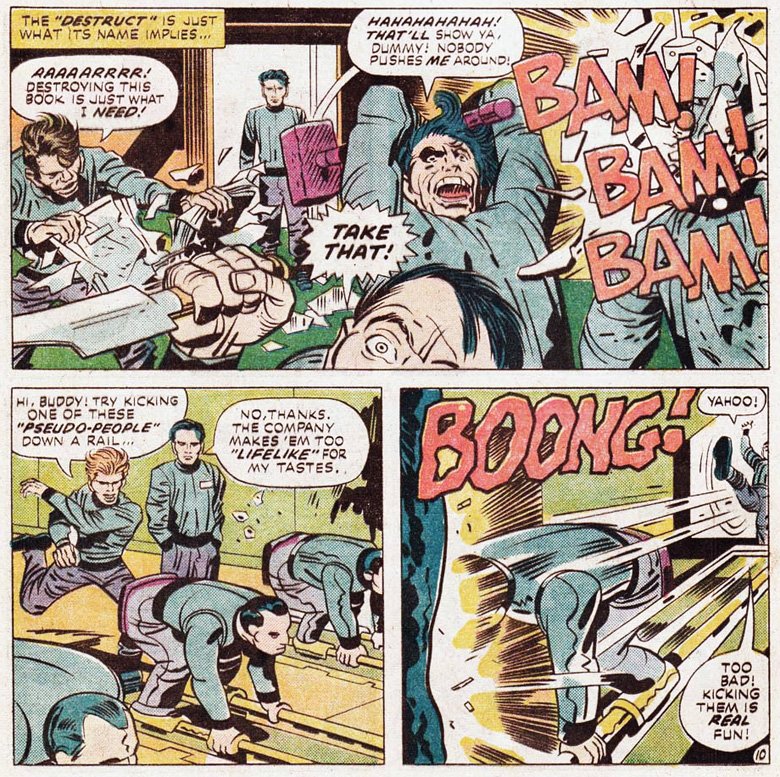

Buddy Blank—the average joe who gets blasted with "electro-hormone surgery" by a satellite named Brother Eye in what's essentially a sci-fi version of Captain America's origin—lives in a particular sort of dystopia that seems especially relevant today. He works in a factory where employees are encouraged to deal with the stresses of their jobs by going into a "Destruct Room" and smashing up its contents with weapons of their choice, and if that sounds a little familiar, there's a reason for that. For one thing, it was a gag that was used on Delocated, but it's also a business that exists in real life. You can give it a shot yourself if you're ever in California.

It's also worth noting that the company Buddy works for, Pseudo-People Inc., is in the "Build-A-Friend" business, which is basically the Comics Code-approved way of saying that they make highly realistic sex dolls capable of passing as real people—which, if you were wondering, is why there's a smiling disassembled lady on that cover. Buddy even hits his breaking point when his only friend at work, Lila, is revealed to be one of the Build-A-Friends, and that her entire "friendship" with him was a test to see if the Pseudo-People were good enough to get close to government officials in order to assassinate them.

And be honest: if that actually happened right now, if there was a news story about a politician who was killed when his RealDoll turned out to be an IED, would you be even a little bit surprised?

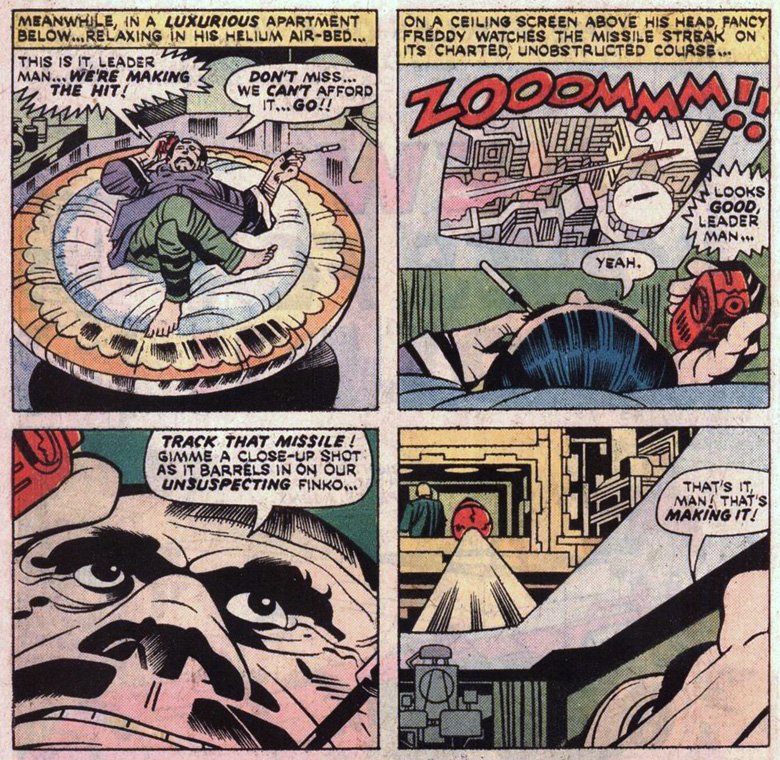

Kirby's take on air strike footage

There's more, too. In the book's fifth issue, in which OMAC takes on a conspiracy among the super-rich to swap their brains into younger bodies, there's a scene where the villain orders a traitor's execution by missile launcher, lounging in his apartment and watching the hit go down via television.

In 1974, I have to imagine that this seemed like an incredible bit of decadence, but today, when we've all seen footage of airstrikes shot by cameras mounted on the noses of missiles, aired over and over again on prime-time TV? A reader wouldn't even raise an eyebrow.

There's even a scene where OMAC spends some downtime between missions living out an "interactive movie" on a set of "mind-phones," a typically Kirbyan name for something that looks a whole lot like modern VR gaming. If there were a couple panels of OMAC waving around a set of Vive handsets trying to unsuccessfully rotate some weird cylinder, then I'd probably just go ahead and declare Kirby to be a full-on prophet.

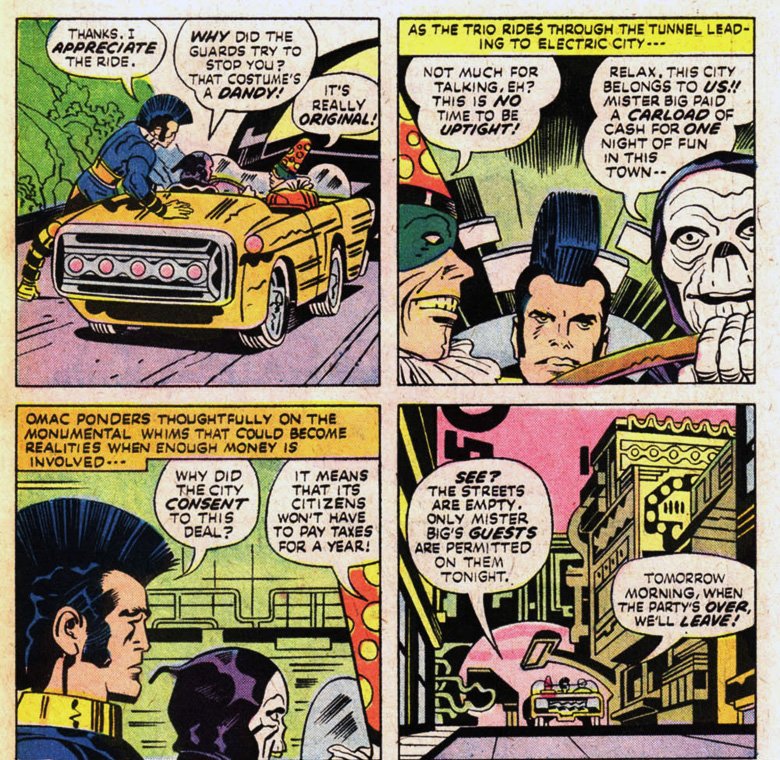

The City of the Super-Rich

Don't get me wrong. As easy as it is to find the metaphor in scenes like the one where a murderous member of the One Percent convinces an entire city to evacuate for the night by promising that they won't have to pay taxes so that he can stage a citywide deathtrap masquerade murder ball, not everything in this comic is an eerie prophecy of life in the 21st century. At the end of the day, it's still a comic book about a man with the ability to suplex a tank getting into fistfights with would-be conquerors.

But at the same time, that's the big trick, isn't it? It's the same reason that people still talk about the social satire of Star Trek 50 years after its debut—even when it was as heavy-handed as the episodes where a computer ordered citizens to file off to their own deaths after running a cost-benefit analysis of war or when Frank Gorshin showed up literally painted half black and half white to point out the folly of racism, wrapping those concerns up in the trappings of a sci-fi adventure story makes them interesting in a way that just writing about the potential for networked computers in the pages of Popular Mechanics wouldn't. It allows for creativity, and as his track record will show, that's something Kirby had to spare.

And because of that, it allows him to take that necessary leap beyond the existing science. That's what makes OMAC so interesting, that when Kirby takes that one step past the logical extreme, he somehow manages to land on something that feels familiar to us over 40 years after it was originally published, when we're living in a world that's dramatically different from the one he saw when he looked out his window.

Kamandi: The Last Boy On Earth

One more thing that's really worth noting about OMAC: while it's decidedly dystopian, it's also a firmly pre-apocalyptic story. The problems that OMAC deals with in The World That's Coming—the vaguely futuristic phrase that represents Kirby's only name for the not-too-distant future era that he's creating in these pages—are the ones that need to be dealt with before they get to that point. They're the things that could kill the world, from the old pillaging the bodies of the young to the slow stranglehold of the super-rich to resource shortages created and perpetuated in the name of profit. If it's a cautionary tale, it's not the hopeless one that "Days of Future Past" is. It's the one that shows us that, as the book says, "OMAC lives so that man may live."

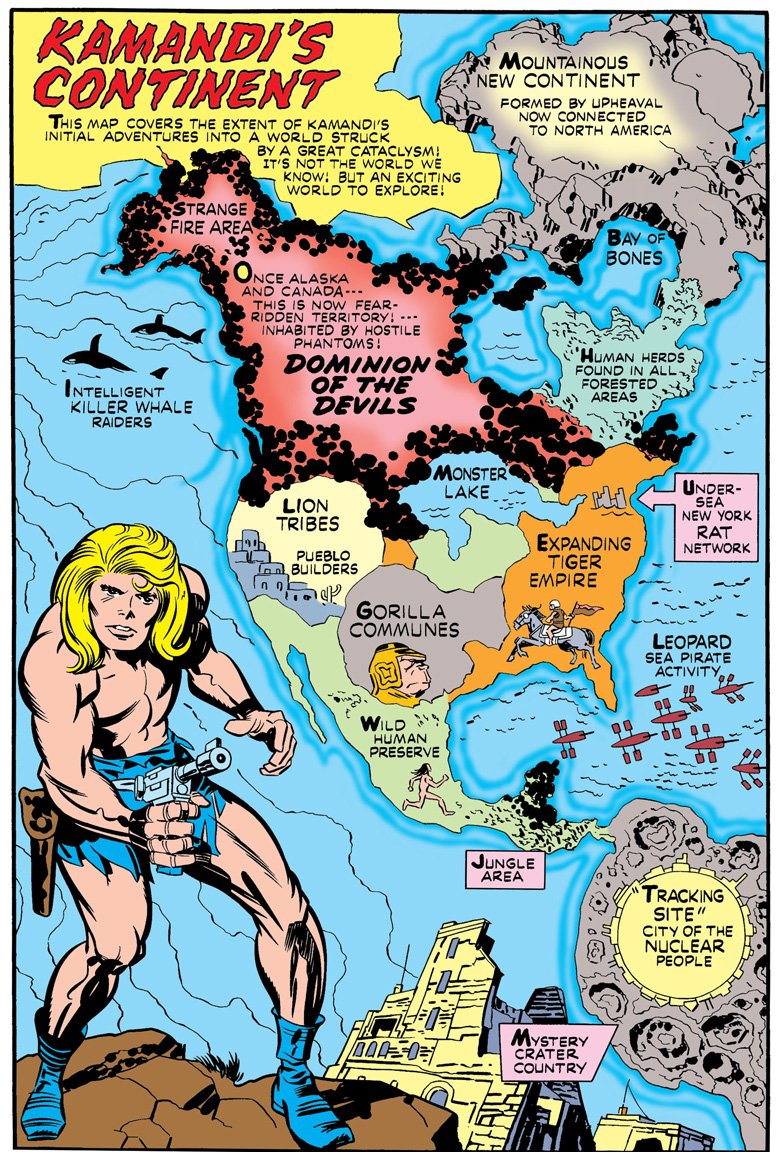

What makes that so notable is that at the same time OMAC was being published, Kirby was also working on another vision of the future. In Kamandi: The Last Boy On Earth, Kirby was obviously riffing on Planet of the Apes, sending his blond-haired, jorts-wearing protagonist into a world where mutant animals controlled everything, and where humans were regarded as animals that were barely even good for hunting.

OMAC takes place before what Kirby called the Great Disaster—a catchall term for armageddon that eventually worked its way into DC continuity as the reason the 31st-century Legion of Super-Heroes didn't know everything about their present-day counterparts—and shows its main character working tirelessly to prevent it. Kamandi, on the other hand, is set on Earth A.D.—After Disaster, natch—and while it's a lot more fantastical, it's also a world that's decidedly past the point of repair.

In Kamandi's world, the idea isn't that he can one day restore civilization, it's that he has to figure out how to navigate a world where everything that we know has been changed into something strange and terrifying. As fun as it is, and as goofy as some of the ideas on display might seem, it also contains some of Kirby's most depressing elements, like the story where Flower—a human woman who's been tagging along with Kamandi for a few issues and feels like the character that proves humanity isn't entirely lost to its more animalistic instincts—is gunned down by a mutant puma motorcycle gang.

Earth A.D.

The good news is that our world looks more like The World That's Coming than Earth After Disaster. For now, at least.

I mean, c'mon. The northwest might've become a Strange Fire Area already, but we're probably at least two weeks away from having to deal with an Expanding Tiger Empire taking over Florida, right? Right.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."