That's What's Up: Do Batman's Parents Need To Be Honest And Incorruptible?

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: What do you think about Telltale's Batman origin? Do the Waynes have to be an honest and incorruptible family? — @Rafa_Rosa

Look, I need to be completely real with you right now. I love Batman. He's my favorite character in the entirety of fiction, and if I had the choice to read a story with him in it or virtually anything else in the world, the only thing I would choose over Batman is a check with my name on it, and once that was done, I'd probably use the money to get more stories about Batman. I love the epics, the smaller stories, the secret origins of the stuff he keeps in the Utility Belt—I even have an entire book about the neighborhoods and landmarks of Gotham City that was printed for a roleplaying game that I've never played, and I've read that thing cover to cover. Twice.

But with all that said, there are very few characters I care about less than Thomas and Martha Wayne.

Get used to seeing this

Don't get me wrong, it isn't that I hate Batman's parents or anything. It's that as characters, well, they're not really characters at all. They're a couple of walking plot points who only exist to walk into Crime Alley and soak up a couple of bullets so we can get to the good part of the story—you know, the part where a guy dresses up like Karate Dracula so he can go punch out a crossword enthusiast who's trying to turn the world into apocalypse times. Everything that happens before that is just set dressing that lays the groundwork for all the stuff we're actually here for.

I'll admit that this is a harsh judgment, and it's based in an argument that you can follow to a conclusion where it applies to everything in comics. If the Waynes are just a narrative convenience to get through the origin story, then you could probably say the same for Alfred, who serves primarily as someone for Batman to explain the plot to, basically just a sounding board with a feather duster. Robin's just there to be rescued! And the villains? They're the biggest narrative conveniences of all, because they provide the inciting incident that allows Batman to do all the cool stuff!

It's a slippery slope of dividing characters up into the ones we want to read about, and it's complicated by the fact that a lot of those walking plot points who were introduced to fill one-note narrative roles—like Alfred, for instance, who was originally introduced as a bit of bumbling comic relief for a story where Batman and Robin had to keep him from finding out their identities while living in the same house—can grow into genuinely great, well-rounded characters in their own right.

At the same time, I do think it's pretty easy to draw a line in this particular case. I will say, though, that the Waynes are by no means the worst offenders.

Jor-El and Lara, Superman's parents

No, that dubious honor goes to Jor-El, who just will not go away, despite having died along with the rest of Krypton in 1938. Well, the rest of Krypton with the exception of his son, his niece, the dog, a monkey, a bunch of criminals who were hidden inside this weird square...

Okay, so it turns out that a lot of people made it out of Krypton's explosion, but Jor-El and Lara are the only two characters whose death was absolutely necessary for the story. It's their sacrifice that sends Superman to Earth, and their act of love—sending their child away to survive while they stay back to die—provides us with the first moment that defines Superman as a character rooted in altruism. It severs his connection with his outer-space origins and allows him to exist as one of us, raised on Earth by a kindly couple who continue to instill those ideas in him through adulthood.

And yet, from very early in the lifespan of the character, there were stories that looked backwards to focus on Krypton and Jor-El, underlining the alien-ness of Superman rather than the humanity of Clark Kent. It hits its peak in the 1978 Superman movie, with Marlon Brando's floating head teaching Clark Kent all about Krypton through the power of magic crystals, and since that movie defined Superman for an entire generation, it filtered through pretty much everything that came after.

Again, this is a function of narrative convenience. It's easy to tell us as readers that Superman's from Krypton and gets his powers underneath Earth's yellow sun, but getting that information to Superman himself is a little trickier. There needs to be some way for Superman to understand his origins so the mystery of it doesn't define his character. More often than not, that defaults to Jor-El and his floating head, leading to stories where Superman's always flying off to the North Pole to ask his dad for advice instead of figuring out his own problems—lookin' at you here, Smallville.

It's not a bad device when used sparingly as a final message, but anything more than that chips away at Jor-El's role in the story. That dude has to do exactly two things: put the baby in the rocket and explode.

Batman's other mom

Compared to Jor-El, the Waynes seem to stick to their role pretty well. In fact, if there's one major complaint I've got about those two, it's that maybe they spend a little too much time getting murdered.

To be fair, though, they've got a much stronger connection to Batman than Jor-El and Lara do to Superman. For Superman, his "real" parents are, for all intents and purposes, Jonathan and Martha Kent—the tragedy of Krypton's explosion is one that's immediately blunted a little bit by giving him a new set of parents who are every bit as kind as the ones who sacrificed their lives. For Batman, though, the surrogate parents are all just a little bit further removed.

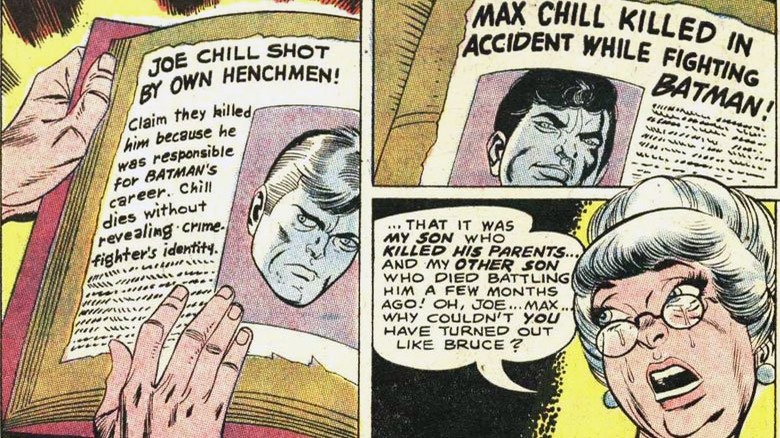

The Silver Age solution for how Bruce Wayne managed to get through his childhood with no parents was the introduction of his Uncle Philip, a world-traveling businessman adventurer whose globetrotting also provided a good reason for Li'l Bruce to be learning the secret arts he'd put to good use as a costumed vigilante. The twist, of course, was that he was primarily raised by Philip's housekeeper, Mrs. Chilton, who—unbeknownst to Bruce but not to Mrs. Chilton herself—was actually the mother of Joe Chill, the gunman who took his parents' lives.

Batman's other dad

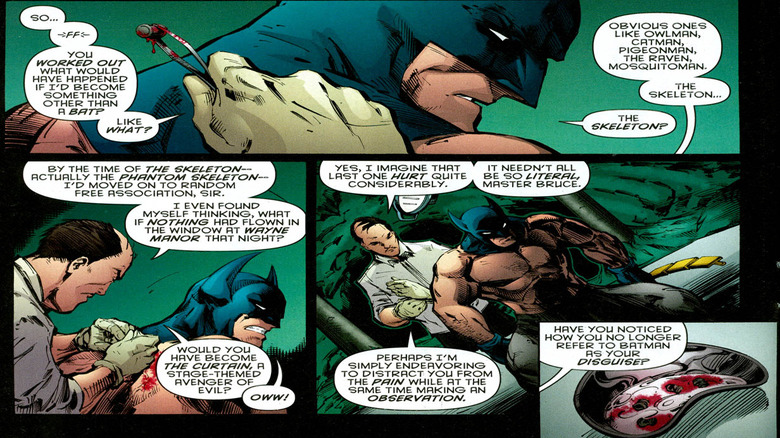

That's pretty weird, but in the Modern Age, the common conceit is that Alfred raised him. It's perfectly fine from a narrative standpoint, as he's evolved into filling the role of a surrogate father in a way that feels natural with regards to how the book works. It's something we've all just sort of agreed on because it fits neatly into the way the Batman mythos is constructed, full of lost parents and the chosen families that people build around them to fill their absence.

In any other context, the fact that this billionaire ten year-old is being raised by his butler is the most buck wild thing in the entire situation, even before you get to the part where the butler is actually a former secret agent who just happens to be super good at stitching up bullet holes and dealing with Joker poisons.

But like Clark Kent's glasses, believing that this is how it works is just part of the price of admission. It's something we accept because the story is built around it, a necessary convenience for the rest of the stories. If you're gonna read Batman, you're going to have to accept that his valet is weirdly suited for providing support to a superhero. Which, incidentally, makes him a way more interesting character than the Waynes, to the point where I'm perpetually shocked that we've never gotten so much as an Alfred Pennyworth solo miniseries.

Thomas Wayne: the first Batman

The Waynes, on the other hand, have made plenty of appearances over the years in an effort to give Batman a connection to his past that goes a little beyond just having a big W on top of a skyscraper in downtown Gotham City.

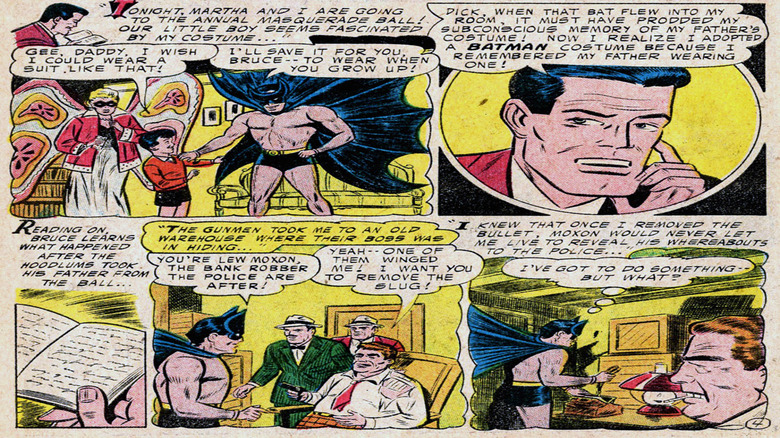

The most famous, of course, was the story of how Thomas Wayne was actually "The First Batman," from the story of the same name by Bill Finger and Sheldon Moldoff. The idea was that on the night of a masquerade ball themed around flying creatures (because why not, I'm sure rich people in 1956 were doing all kinds of weird stuff), Thomas Wayne decided to attend in a bat costume that bore more than a passing resemblance to his son's eventual crime-fighting gear. Naturally, this led to him being kidnapped by gangsters to operate on one who'd been injured in a shootout and then punching them, leading their boss to hire a hitman to murder him in an alley as retribution.

That story originally appeared in Detective Comics #235, and Thomas Wayne's "original" Batman costume has been cropping up ever since as a weird little signifier of the kind of destiny that characters have to grapple with in comics. As much as coincidence is the engine that drives superhero stories, having everything be an echo of something else is the sort of thing that detracts from what makes Batman unique in his universe.

The Waynes

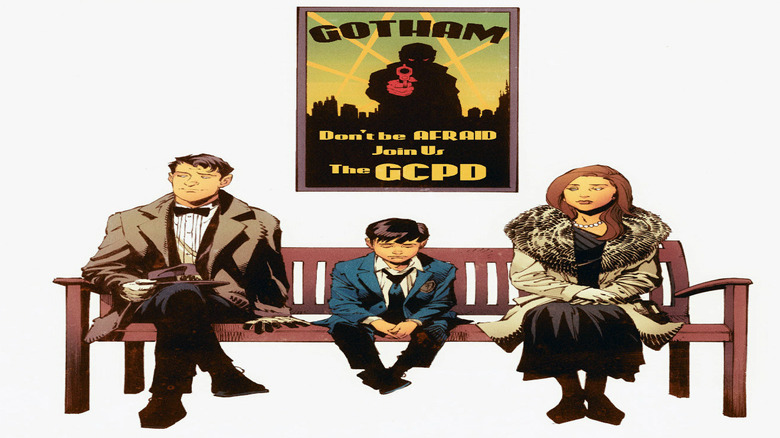

All of which is to say that the Waynes aren't as important to the story as you might think. They're a means to a bunch of particular ends—the motivation for Batman's heroism, the family fortune that pays for all the batarangs and rocket cars, the ancestral home that's conveniently situated over a system of caves that somehow have wifi—but beyond that, they don't have a lot of requirements. The only thing they really need to do before they take that left turn down Crime Alley is provide Bruce Wayne with a happy childhood.

I've always been a little mystified by stories built around the idea that Bruce was an unhappy child. Batman's entire motivation comes from loss, and that loss is so much more profound if he's happy as a kid—and it needs to be a pretty profound loss if we're going to accept that it motivates someone to devote his entire life to haunting the night and waging war on all criminals. Joe Chill's two bullets need to destroy not just two wealthy philanthropists, but the entire idea of what parents represent: safety, comfort, love, and protection.

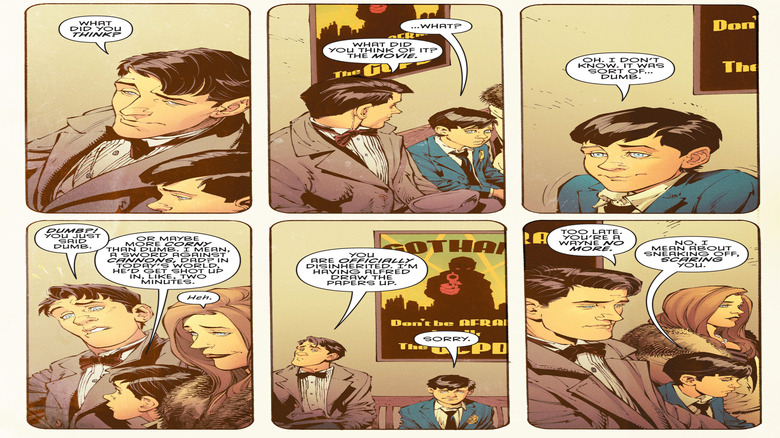

Thomas Wayne has strong feelings about Zorro

It's worth noting that these two ideas don't necessarily have to exist independently of each other. When Scott Snyder and Greg Capullo took their shot at Batman's origin story in the pages of Zero Year, the interactions they showed between Bruce and his parents were all built around the idea that Bruce was dealing with some pretty heavy stuff in terms of psychology. The experience of falling down into the cave and being menaced by the bats that would eventually inspire him left him shaken and withdrawn, driving him to do stuff like sneaking into Gotham—something inspired by Snyder's own childhood growing up in New York during the crime wave of the '80s.

The thing is, they also showed the Waynes reacting to this with compassion, humor, and understanding. They connect to him, and that connection paves the way to get back to those ideas of comfort and safety, right before they all go plunging off a cliff as soon as they walk out of the movie theater. It all builds to that same feeling, and the personal tragedy of how it's taken away.

That's also why the Waynes are so often portrayed as a pair of saints. It's easy to extrapolate the way they're portrayed with Bruce to the much larger scale of Gotham City itself, as a way to justify why things in Gotham are just so bad. Stories like the Christopher Nolan movies operate on the idea that the Wayne murders were the straw that broke the camel's back in terms of crime in Gotham City, tying Batman to his hometown in a very direct way—and that's the kind of approach that requires Thomas and Martha to be Good People with capital letters.

But do they need to be?

Telltale's Thomas and Martha Wayne

Which brings us back to the question of how the Telltale games present the Waynes. I won't spoil it for anyone who hasn't played it—and in full disclosure, I'll admit that I haven't had the chance to do so myself, although I've read up on the plot and discussed it with a couple of friends who have—but the short version is that its version of Thomas Wayne isn't quite the saint that other versions present.

I've been asked about how I feel about that sort of approach, and the truth is that just based on that, I don't really mind it. If nothing else, it's the kind of setup that allows a story to focus on Bruce Wayne rather than Batman, and serves as a reminder that those two identities aren't as far apart as they're sometimes portrayed. That alone makes it an inherently interesting take.

But more importantly, it doesn't actually break anything. A Thomas Wayne who's on the shady side of things can still be a Thomas Wayne who loves his family, and as long as that necessary element is present in the way he relates to Bruce, then the origin story and the nature of Bruce Wayne's personal tragedy is still as affecting as it ever was. Plus, on a more fundamental level, it allows Batman to address a weird sticking point about the way his character is built.

The decision to fight crime

It's something I've written about before, but Batman is, at heart, a child's idea. It's why it's so important that the murder happens when he's young, because only a child would decide to devote his entire life to fighting crime in the specific way that Batman does—a way that, in the real world, would be bananas. It's why his parents don't need to be fleshed out as fully-formed characters, because they're a child's idea of what parents are, a shorthand stand-in for safety and comfort.

But even if we accept that with the same eagerness that we accept a butler with James Bond training raising a billionaire orphan, it's still rooted in a child's idea of what's possible. Asking Batman to re-examine the ideas that he had as a child—ideas about his parents and their inherent Goodness, in the case of the Telltale games—is asking him to examine the decision to become Batman, too.

Normally, that's a bad idea, because the entire universe is built around showing us that being Batman is a perfectly reasonable and effective response to trauma in this world—if it's not, then we're all just wasting our time, and the whole thing collapses under its own weight. But by giving him something that's just close enough to poke into, it allows you to explore his reasoning without hanging a lampshade on the fundamental truth of the universe that allows these stories to be told in the first place.

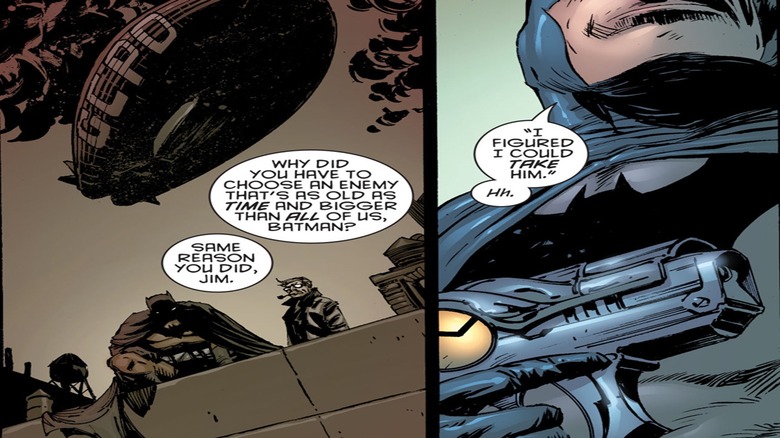

The only real problem is that we already know the answer to any questions that raises. If Thomas Wayne really was a bad guy, then Batman has a surrogate father figure right upstairs polishing the silverware. If the question is about whether Batman has done enough good in the world to balance out his parents' crimes, then that answer is pretty easy, too, as he's currently living in a world where billions of people have not been murdered by Ra's al-Ghul. The fact that he's Batman, and that Batman has done tangible good in this world, means that the rest of it is just an exploration of what it all means.

So in that respect, it really comes down to the execution. As we all learned when Bucky came back to life as a brainwashed Soviet assassin with a cybernetic arm—uh, spoiler warning for Captain America: The Winter Soldier, I guess?—there aren't a lot of ideas that can't turn out awesome if they're done well. For Batman's parents, their status as these symbolic plot points who walk around in a mustache and a string of pearls make them uniquely malleable in that regard.

Personally, I think it's better if they're good people, in the same way that I don't think it's a good idea to have Jon and Martha Kent burying bodies under the cornfield. But that doesn't mean that you can't pull it off—it just makes it harder.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."