How The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy Differs From The Books

Adapting a beloved book into a movie is a difficult, precise operation, like re-entering the atmosphere in a space shuttle, or making porridge for Goldilocks. You have to get it just right, balancing demands for fidelity to the source material from the book's devoted fans while also making sure the film stands on its own merit and tells its own story. Cater to the fans too much, and you turn the book into a lifeless theme park ride that has all the right things for devotees but barely makes sense to new viewers. Stray too far from the book and you've got a fandom riot on your hands.

"The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy," the 2005 adaptation of the first book in Douglas Adams' beloved science fiction series, nobly attempts this balancing act as best it can. The book was adapted rather faithfully from its original form as a 1978 radio series, and as a result it flows conversationally from subject to subject, with little by way of character development or a tight narrative. The movie, then, had the immense challenge of turning a book that feels like being rambled at by an old, spacefaring friend you haven't seen in a while into a compelling narrative with a distinct beginning, middle, and somewhere in there it also had to work in a philosophical message that's both extremely silly and surprisingly profound.

Did they pull it off? Here's how "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy" differs from the books.

An opening musical number

The hardest part of adapting "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy" is losing the voice of the narrator. As fans might remember, the book is written in what's known as third person omniscient narration — the narrator is an external presence that knows things the actual characters don't — and no narrator is as omniscient as this one. Beyond including full passages from the titular Guide, which is a text within the text, the narrator can see into the distant future and alternate dimensions, and is generally full of tangents that the characters in the story aren't aware of, and are thus difficult to include in the film. Stephen Fry does replicate some of it with his impeccably British voiceover, but there are many that just don't come up.

One of the best moments in the movie, and the first big difference from the book, is the opening title sequence, where the filmmakers make use of the information provided by the narrator that dolphins are in fact the second most intelligent species on Earth (one ahead of humans), and managed to leave before its destruction with a message to humanity: "So long, and thanks for all the fish." The opening credits feature a snazzy musical number, with dolphins leaping and dancing to a song with that title, with hilarious original lyrics: "Despite those nets of tuna fleets/ we thought that most of you were sweet."

A most definitely inspired casting choice

One of the more conspicuous differences from the book is the casting of rapper and actor Yasiin Bey, then known as Mos Def, as Ford Prefect. In the books, though he's actually an alien "from a small planet somewhere in the vicinity of Betelguese," Ford is posing as an out-of-work actor from Guildford with "wiry and gingerish" hair, and he's almost certainly white. Indeed, the character was played by a white actor, David Dixon, in the 1981 BBC television adaption.

Bey's casting adds a very welcome element of diversity to an otherwise all-white movie, but he also gives the character a jerky, strange physicality that is right in line with the description of Ford in the book. As described, Ford's eyes "don't seem to blink often enough," and he "smiles a little too broadly." Bey plays Ford as having to stop and think before he speaks to Arthur, perhaps translating things into Earth terms in his head. While the casting represents a change from the source material, the actual characterization remains remarkably faithful.

A superfluous love triangle

By far the biggest difference between the book and the film is the relative importance of Arthur and Trillian's relationship. While both stories introduce that relationship in the same way — with Arthur chatting Trillian up at a party and the alien Zaphod Beeblebrox swooping in to take her away — in the book this is never mentioned again. It's not even entirely clear if Zaphod and Trillian are dating or if she just took up his invitation to travel the galaxy, and she and Arthur never so much as flirt during their adventures. The fact that they'd met before at a party is mostly just there to prove how the Infinite Improbability Drive generates coincidences.

In arguably the movie's biggest weakness, Arthur and Trillian get played up into an entire "love conquers all" storyline that has nothing to do with the spirit of the original work. Arthur's still moping about her as the film begins — he even has a picture of her on his 2005-era flip phone — and when they meet again it's played for cringe-inducing awkwardness. Zaphod becomes a possessive jerk when he feels threatened, and near the end of the film Arthur speculates that the question of "is she the one?" is even more important than the deep, philosophical questions pondered by the supercomputer Deep Thought. Martin Freeman and Zooey Deschanel do fine with what they're given, but the entire romance angle is dead on arrival.

One head is easier to depict than two

In the book, the bumbling, egocentric President of the Galaxy Zaphod Beeblebrox has two heads, side by side, and three arms total: one on the left, two on the right. Sure, this isn't very easy to depict visually, and your mileage may have varied on the BBC TV version's solution, with one fake arm that's obviously rarely moving and a downright creepy animatronic second head. But the way the movie just punts on Zaphod's anatomy and sticks with actor Sam Rockwell's natural shape 99% of the time is one of the bigger disappointments for devoted "Hitchhiker's Guide" fans.

In the film, Zaphod's second head hides in his chest, sort of like he's a two-headed turtle with the heads stacked on top of one another, and his third arm spends most of its time retracted into his chest as well. A bit of dialogue implies further that he created the second head to split his personality into two, saving the less "presidential" parts for the second one (when his rival Humma Kavula removes the second head as collateral, Zaphod seems dimwitted and confused without it), in contrast to the books where it seems to be a natural trait of his species. Not only does the movie mostly pass on depicting Zaphod in the way the book describes him, it seems to go out of its way to raise more questions than it answers about his biological nature.

The Improbability Drive is a lot more probable

The depiction of the Infinite Improbability Drive in the movie version of "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy" is a letdown by any standard for book fans. Reasonably, they'd need an infinite budget and some method of breaking several different laws of physics as we understand them to truly stick to the psychedelic, reality-bending way that Douglas Adams describes, but the movie also suffers from a painful lack of imagination. It might have been impossible, but they hardly even tried.

All we get in the film is one quick scene when Arthur and Ford have turned into sofas, one moment when the entire Heart of Gold gang are sock-monkey-like puppets, and of course the iconic, faithfully depicted sequence when in which two nuclear missiles are turned into a flowerpot and a sperm whale. But with a big studio budget to work with, the filmmakers could have gone full "2001: A Space Odyssey" with every Improbability drive sequence and tried to get more into the spirit of passages from the book, which imply a kaleidoscopic endlessness the film doesn't even approach: "Primal light exploded, splattering space-time as with gobbets of Jell-O. Time blossomed, matter shrank away."

Double your Vogon pleasure

Since the "Hitchhiker's Guide" book just kind of follows our heroes as they wander from place to place, the movie felt the need to give them more consistent antagonists. So the Vogons — the unpleasant, bureaucratic poetry-enthusiasts that disappear in the book after throwing Arthur and Ford out the airlock — have a much more expanded role in the film as the incompetent Stormtroopers that somehow manage to find the main characters everywhere they go and start shooting lasers wildly. They kidnap Trillian at one point, requiring an entire sidequest to the Vogon homeworld to rescue her that's not in the book at all, and the mildly amusing creatures that slap you every time you think are the only particularly unique part of the entire addition.

The Vogons also show up at the end of the movie in the company of the Galactic Vice President (also an invention of the film) to incoherently shoot at our heroes for kidnapping the president, even though the president, Zaphod, is clearly with them. The Vogons work perfectly in the novel as our entry point into space in the first act, but without any sense of them or their leadership as characters, they make no sense as the antagonists presented in the movie.

The entirely inexplicable Humma Kavula

The "Hitchhiker's Guide" movie also invents a political rival for Zaphod, a religious leader named Humma Kavula who lost the presidential election. The Improbability Drive, as if guided by the hand of the screenplay itself, brings Zaphod to Humma's homeworld of Vildvodle VI, where Zaphod seeks him out to yell at him for calling him stupid during the campaign. Suddenly, Zaphod seems to remember that his rival is menacing and creepy, as the eyeless, half-robotic Humma sinisterly creeps forward. Book readers, and indeed, most fans coming into the movie cold, are likely just confused.

In fact, everything about Humma Kavula is confusing, and unlike other parts of the film, no helpful voiceover from the Guide pops in to help us understand anything about his planet or his strange, sneeze-centric religion. He seems to exist solely to kidnap one of Zaphod's heads and hold it hostage in return for a special gun stored near Deep Thought, and that plot thread isn't even resolved before the film is over. John Malkovich is memorably weird as Humma, but the entire sequence doesn't even begin to justify its own existence.

A real exposition expo

Although it doesn't have particularly cinematic beats, the structure of the original "Hitchhiker's Guide" book is part of why it works so well. We follow our relatable human everyman, Arthur, as he stumbles through a confusing, aimless journey, and in the end are let in on huge secrets about the nature of not just Earth, but the entire purpose of life in the universe. After a series of improbable events without explanation, we learn that Arthur is the result of an impossibly huge grand experiment to explain literally everything. It's a disorienting, delightful rug-pull.

The movie, once again most likely to make the story more compelling in a conventionally narrative way, has Zaphod explain half of the big existential mystery roughly halfway through the plot. He somehow has footage from the "Magrathean archives" that show the creation of Deep Thought and the calculation of The Answer (42, for the uninitiated) and states his intention to find The Question and exploit it for his own gain. This not only does a disservice to Zaphod's character, making him even more crass and cynical than his book counterpart, but it undercuts the entire pacing of the story. Now, halfway through, it becomes a Big Quest for Ultimate Meaning, which fans of the book know isn't the point. By tipping its hand too early, the movie shifts the narrative balance, giving us far too much time to consider what The Question might actually be.

Deep Thought is much more mythic and mystic

The "Hitchhiker's Guide" movie's depiction of Deep Thought is a somewhat sideways departure from the book, one that unlocks more tonal differences the more you think about it. In the book, Deep Thought is similarly massive, the "size of a small city," but all the dramatic conversations with the computer take place in a "specially designed executive office," one that has all the sleek, technology obsessed-trappings of contemporary business. That beings communicate with Deep Thought in such a mundane setting perhaps represents the commodification of meaning and purpose by the capitalist societies with which Douglas Adams was familiar.

The movie, conversely, makes Deep Thought into a giant, sculpture-like obelisk that evokes something more like the religious awe of temples or pyramids. Instead of "soberly dressed" programmers with briefcases, Deep Thought is address by beings in flowing robes and wigs, and the whole sequence takes on a much less secular undertone. It's a significant change, especially as the next step after Deep Thought calculates The Answer is the commissioning of the Earth. In the book, the Earth is the result of a desk console trying to calculate the bottom line for some number-pushers. In the movie, the Earth is the creation of a sphinx-like, nearly supernatural being with the voice of Helen Mirren, and a bit of the irony is lost.

The point-of-view gun

It's easy to have sympathy for the screenwriters who inserted a love triangle into "Hitchhiker's Guide" to give it some sort of dramatic tension to resolve. That sympathy dries up quite a bit at the end, however, when the mysterious gun that Humma Kavula sent Zaphod to retrieve turns out to be a magical "point-of-view gun" that resolves the plotline without any of the characters actually doing anything interesting or dramatic. The gun telepathically makes the person who gets shot feel the feelings of the shooter, and Trillian uses it to make Zaphod feel (and also, helpfully, narrate out loud) how she's feeling about him, about the Earth's destruction, and about Arthur.

It would be worth the stilted, awkward scenes in the early going if the love story became a meaningful part of the plot by the end, but the movie manages to resolve it as half-heartedly as possible while also breaking the traditional "show, don't tell" rule of storytelling about as badly as a movie can.

Marvin saves the day slightly differently

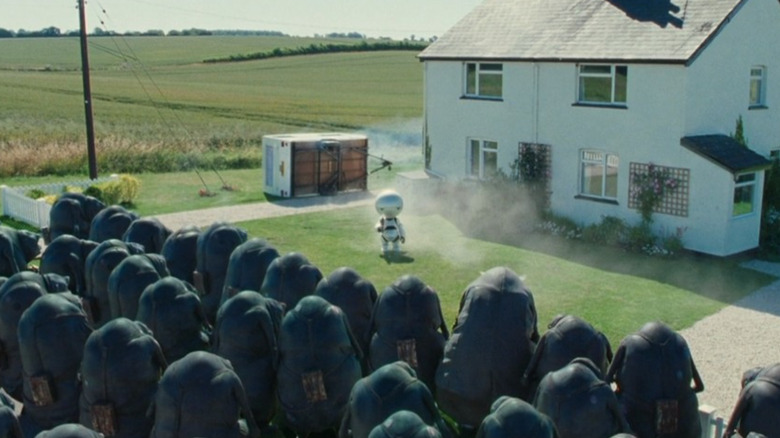

We've been pretty hard on the "Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy" movie so far, but we do have to admit that its alterations from the source material combine for one fun moment in the end, when Marvin the Paranoid Android saves the gang from certain peril in a scene that recreates part of the book with different, more cinematic ingredients. In the book, Arthur, Trillian, Zaphod, and Ford are pinned down by heavy fire from two intergalactic police officers who show up out of nowhere, then suddenly stop firing when their life support systems inexplicably fail. After investigating, the gang learns that Marvin had been talking to the computer on the police officers' ship, which controlled their life support — during conversation with the famously negative Marvin, the computer became so depressed that it killed itself.

In the movie, the Vogons show up en masse instead to fire wantonly at Arthur's recreated house on Earth 2.0, and the only thing that stops them is Marvin firing at them with the point-of-view gun, making them all so depressed they give up and lie down. It's true to the random spirit of the novel, but done on the movie's terms, which is exactly the kind of moment this film needed more often.

The movie cuts out the book's anti-establishment bent

Considering the rambling, diverting way that it's written, it would be impossible to include or depict everything that takes place in "Hitchhiker's Guide" on the silver screen. But it's subtly telling that the things the movie leaves out are generally the things that argue against society's status quo. There's a moment on the Vogon ship when Ford nearly convinces a low-level Vogon to quit his thankless, repetitive job that the movie leaves out. The philosophers that at first are concerned Deep Thought will put them out of a job, and then spend 7.5 million years becoming rich while waiting for the Answer, is another important omission — there no answers, and you shouldn't trust anyone who says they have one.

Also missing is one of the best jokes in the novel, about how the Marketing Department of the Sirius Cybernetics Corporation are listed in the Guide as "a bunch of mindless jerks that will be first up against the wall when the revolution comes." This critique of the forces of technology and marketing pairs well with Adams' introduction about how most people are unhappy and entirely too concerned with "small, green pieces of paper" and "digital watches," which is also not in the film. There are many more examples, but suffice it to say that in removing certain parts of the book, the movie mutes a lot of the subversive wit that makes "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy" so enduring.