The Untold Truth Of The DC Animated Universe

2022 marks the 30th anniversary of "Batman: The Animated Series," and it's a milestone near and dear to the geek heart. Created by Eric Radomski and Bruce Timm — the latter would further develop the show alongside Paul Dini and Mitch Brian — the beloved animated classic only lasted for two seasons, but its acclaimed 85-episode run launched the DC Animated Universe (DCAU), which would ultimately include eight distinct series from 1992 to 2006 and six feature films. As Timm and Dini became the stewards of these cartoons, they found themselves dealing with the expectations of studio executives, as well as fans familiar with conflicting depictions of various DC Comics characters, all while trying to stay true to their own vision.

While these shows are generally loved by critics and fans alike, a deep exploration of their creation reveals fascinating details about how the DCAU was developed, as well as its impact on DC Comics. Overall, the DCAU not only revolutionized animation in the United States, but forever altered the future of comic books and the media they inspired.

Caught between Adam West and Tim Burton

Prior to the DCAU's launch with "Batman: The Animated Series," the average consumer knew Batman primarily from two sources: the 1966 "Batman" show starring Adam West, and the Tim Burton-helmed film franchise, which, in 1992, had just released "Batman Returns." These two very different versions of the character forced the DCAU to find a middle ground that could stand on its own.

Though often criticized for being overly campy, 1966's "Batman" was extremely popular — some might say too popular. "Watched by millions at the time, and millions more over subsequent years in syndication, the show reinforced in the public's mind the silliness and irrelevance of superheroes — and, by implication, comic books — in contemporary culture," wrote Bradford W. Wright in his 2003 book "Comic Book Nation."

By the late 1980s, however, Frank Miller's monumentally influential "The Dark Knight Returns" had reframed Batman as a serious character for adults, and Tim Burton's visually and emotionally dark depiction of the Caped Crusader gave film audiences a new love for the character. As a result, those working on "Batman: The Animated Series" had to craft a show that both sets of viewers could enjoy. The end result touched on Burton's bleak depictions of Batman and Gotham City while also echoing elements of West's version.

More than a toy commercial

During the early history of television, there was widespread concern for how this new technology could influence children. To protect America's youth from marketing manipulation, regulations existed that limited how much advertising could be directed at kids. This changed, however, with the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980.

"Along with the deregulation came many other changes in children's television," Irvin Molotsky wrote for the "New York Times" in 1988. "Toy manufacturers, for example, became heavily involved in children's programming, developing shows based on toys that, in some cases, broadcasters were enticed to schedule in exchange for a part of the profit on toy sales."

In short, for much of the '80s and '90s, kids' cartoons largely functioned as toy commercials. In the 2018 documentary "Heart of Batman," Sidney Iwanter, then Vice President of Programming for Fox Kids, discusses how animators had to primarily worry about "making sure that the toys were sold, but also keeping the various pressure groups off their backs." This commercial focus often constrained what cartoons could do.

The team working on "Batman: The Animated Series" understood these practicalities, but they were after more than just merchandising. The show managed to walk the narrow tightrope of being appealing to kids while also telling stories with emotional depth. It was still a children's cartoon, but it was a children's cartoon that their parents could enjoy, too.

Revitalizing American animation

The history of American animation isn't just a history of Walt Disney, who would never have been successful without "the Nine Old Men," Disney's original animators. These were the creative legends who brought stories like "Peter Pan," "Alice in Wonderland," and "The Jungle Book" to life in animated form. By the 1970s, however, members of this generation of animators had started to retire, and no new group had arisen to pick up the baton as artistic leaders.

"The industry just wasn't thriving," Bruce Timm says in the "Heart of Batman" documentary. "A lot of the earlier generation, the famous Nine Old Men, the star animators going back to the 'Snow White' days, a lot of them were retiring or dying off and there didn't seem to be a whole new generation of people who were being mentored."

It was in this void that the Warner Bros. Animation team formed — with the help of Steven Spielberg, who collaborated with them to produce popular and critically acclaimed shows like "Tiny Toon Adventures" and "Animaniacs," and whose involvement ensured that the studio was given a healthy budget. By the time Spielberg moved on, Warner Bros. Animation was a well-oiled machine, with an ambitious crew ready to establish their own legacies and take up the mantle of the Nine Old Men. As art director Glen Murakami put it, "That was ... the new revival of animation in the '90s."

Superman arrives

Though extremely popular, "Batman: The Animated Series" only lasted for two seasons, and after it ended, much of the team would be moved to work on "Freakazoid." However, with the series being a success and Warner Bros. having larger plans for Superman — a new '90s live-action film would have been directed by Tim Burton and starred Nicolas Cage as the Man of Steel — Bruce Timm was approached with the opportunity of creating a Superman animated series. The Burton/Cage movie was ultimately canceled, but the cartoon lasted three seasons on Warner Bros.' own network, the WB, depicting a powered-down Superman who, like Timm's Batman, had the emotional depth necessary for audiences of all ages to relate to him.

In addition to avoiding the mullet Superman/Clark Kent was sporting in the comics at the time, the creative team for "Superman: The Animated Series" modernized Superman's villains to make them more relevant and less goofy. More importantly, this was the series that officially kicked off the DCAU as a shared universe. With Fox's rights to Batman expiring and the WB launching, Warner Bros. brought Timm back to Gotham with "The New Adventures of Batman" in 1997, while "Superman: The Animated Series" was still on the air. The three-part story "World's Finest" — which found Batman and Superman teaming up — was so successful that the two shows crossed over three more times, paving the way for the larger team series that was coming.

Assembling the Justice League

"I will never do a Justice League show," Bruce Timm said in a 2000 interview. "There's just too many characters in one series ... And, of course, with the Justice League, you're talking about characters who all have the powers of gods, so you can't just have them fighting thugs, fighting guys robbing banks; they have to be fighting, y'know, huge criminals every time, so you're talking huge set pieces."

Luckily, one of the many benefits of the DCAU is that its storytellers can experiment with new ideas, and in some cases, realize that they might not be as difficult as initially believed. In November 2000, audiences saw a future version of the Justice League appear in a two-part "Batman Beyond" episode titled "The Call." Having successfully pulled off some larger set-pieces and gotten a feel for how to stage the characters, Timm realized that he and his team could produce Justice League stories, and went to work developing "Justice League" for Cartoon Network.

The show ran for two seasons, but was immediately followed by three seasons of a successor show, "Justice League Unlimited" — which also happened to be name of the future version of the team in "Batman Beyond." Some of its creators felt the show worked because it initially streamlined or ignored backstories so characters would have less narrative baggage to communicate, and JLU's ability to have each episode feature different superheroes helped make it a rousing success.

A laboratory for new characters

One of the greatest parts of the DCAU legacy is the wealth of new characters it introduced, and without question, the most successful of these creations is Harley Quinn. First appearing in "Batman: The Animated Series," Harley was initially designed to be just a slightly more visually interesting member of the Joker's gang, but the character had a major cheerleader in the form of Paul Dini, who brought her back for eight more episodes. Dini also fleshed out her backstory as Dr. Harleen Quinzel, an Arkham Asylum psychologist who fell in love with her patient, the Joker. And because Dini was also a comic book writer, he ended up translating her into that world, as well — the 1994 single-issue story "Mad Love," written by Dini and Bruce Timm, won an Eisner Award, and Harley was officially folded into DC Comics canon in 1999. She went on to become one of DC's most popular characters, appearing not just in the comics, but in more DCAU shows, numerous video games, and more recently, her own live-action movies and animated HBO series.

Other characters introduced to DC Comics by the DCAU include Renee Montoya, Mercy Graves, Livewire, the Gray Ghost, Volcana, and Terry McGinnis — better known as the Batman in "Batman Beyond." While none of these characters would become quite as popular as Harley Quinn, they are all a reminder that comic book adaptations can find success by deviating from canon.

Revamping stale characters

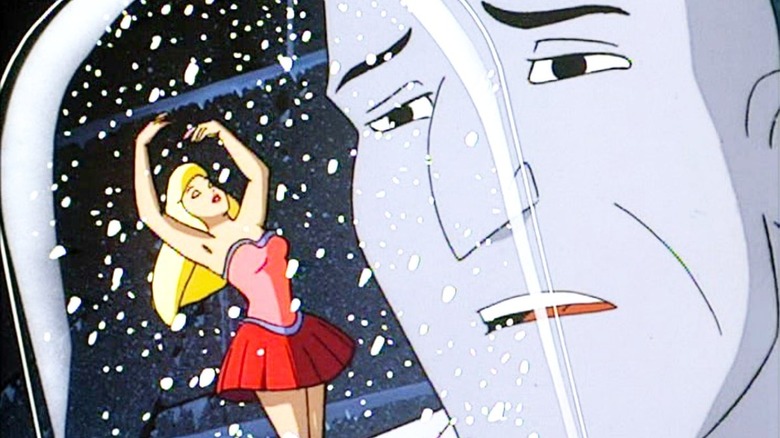

The character of Mr. Zero first appeared in 1959's "Batman" #121, but in a 1966 episode of Adam West's "Batman," he would be renamed Mr. Freeze. For decades afterward, Freeze was treated as just a random quirky Batman villain, until the team behind "Batman: The Animated Series" decided to revamp him. In the show, Freeze's was transformed into a tragic character, as he was revealed to have cryogenically frozen his dying wife so that he could find a treatment for her illness, and turned to crime to fund the research. Suddenly, Mr. Freeze was a sympathetic villain instead of a joke, and this version would become the standard interpretation of the character going forward.

Mr. Freeze is not the only character to have been revamped by the DCAU — others include Static (star of the early 2000s DCAU show "Static Shock"), Clayface, Clock King, Parasite, and Hawkgirl. The DCAU even added unique character connections that would bleed into other media, such as the Supergirl's psychic connection with her clone, Galatea (the DCAU version of Power Girl). The idea that Kryptonians might have such a connection with their own doppelgangers was appropriated for the CW's "Superman & Lois" in 2022.

Embracing moral complexity

When fans think of Batman, Superman, and the rest of DC's primary heroes, they often think of paragons of virtue. Superman and Batman are seen as characters of such strong moral conviction that many fans hated the more complicated representations crafted by Zack Snyder in "Man of Steel" and "Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice." However, it was the DCAU that laid the groundwork for presenting these characters as morally grey. In addition to "Batman Beyond" beginning with Bruce Wayne retiring after he used a gun to stop a criminal, "Superman: The Animated Series" features an episode that ends with a corrupt detective being executed via electric chair.

"Justice League Unlimited" gets complex in another direction, using the character of Green Arrow to question the ethics of the Justice League itself, a coterie of god-like superhumans that functions without authority or regulation. "I'm the only guy in the room who doesn't have superpowers, and let me tell you, you guys scare me," he says in one episode. "What if you do decide to go marching down there, taking care of whoever you think is guilty? Who could stop you? Me?"

From Lex Luthor to Huntress to Amanda Waller to the Justice Lords, the DCAU showed that DC stories could have morally compromised heroes, morally righteous villains, and a more complex understanding of both.

Elevating voice talent

When Adriana Caselotti voiced Snow White in 1937's "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs," she was not formally credited for her work in the film. Walt Disney claimed he didn't want to destroy the connection audiences had with the character — he even refused to allow Caselotti to appear on a radio show, reportedly saying "I'm sorry, but that voice can't be used anywhere. I don't want to spoil the illusion of Snow White."

While later voice actors would not be bound to such strict rules, Disney's views set the standard that animated characters were more important than the actors who voiced them. The result was that for decades, a cartoon's brand functionally erased the contributions of voice actors. This began to change in the 1990s, when animated projects casting well known celebrities. One of the biggest stars to work in the DCAU was Mark Hamill, who became the voice of the Joker to an entire generation of fans. Hamill's version is considered by many to be the best iteration of the Joker.

The DCAU also enabled voice actors like Kevin Conroy to become well known in fan communities. Similar to Hamill, Conroy's Batman is not only considered to be the best version by many, he has also been playing Batman consistently since 1992. Conroy was even able to play a live-action version of the character in the CW's 2019 adaptation of "Crisis on Infinite Earths."

Even Alan Moore liked the DCAU

Alan Moore tends to hate adaptations of his comic books, typically refusing to have his named attached to them or receive any of the profits. However, Moore did approve of the "Justice League Unlimited" episode "For The Man Who Has Everything," which adapted his famous Superman story of the same name.

"For The Man Who Has Everything" revolves around the villain Mongul, who, on Superman's birthday, attacks the Man of Steel with an alien plant called the Black Mercy. Attaching itself to Superman's body, the Black Mercy slowly consumes him while giving him mental fantasies of all the things he most desires. For Kal-El, this means being married to Lois and raising a family on the planet of Krypton, which was never destroyed.

While the animated series made a few changes, Alan Moore allowed his name to be credited on the episode, and DCAU writer and produced Dwayne McDuffie confirmed that "he liked it."

Multimedia multiverse

Multiple versions of the same character existing at the same time has always created a unique pressure. When the editorial team of DC Comics felt that there were too many versions of Earth in their comics, they wrote the massive crossover storyline "Crisis on Infinite Earths" to streamline the overarching universe, making the stories easier for new readers to dive into. Mirroring this concern was the tendency of both DC and Marvel to change their comic books worlds to match those of their television shows and movies.

However, the DCAU showed that DC could have success with multiple versions of characters functioning across multiple forms of media. After all, over the course of its existence, it overlapped with "Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman" as well as "Smallville", not to mention several video games and films. In short, the DCAU showed Warner Bros. and DC that audiences could handle different versions of the same character being simultaneously being produced in different formats. With 2022 featuring four different versions of Batman in the same year, the DCAU can be said to have lain the foundation for the current state of DC Comics adaptations.

Superheroes' first shared universe

Shared fictional universes are so common today that it feels as if they've always been here, particularly when it comes to film and television adaptations of comic books. It's difficult for some to remember a time before the Marvel Cinematic Universe or the Arrowverse — in the old days, movies and TV shows based on comic book properties were isolated, their characters never interacting with other comic book films or series. As such, prior to the DCAU, each DC Comics adaptation was limited to a universe of its own.

In contrast, the DCAU's eight shows (with hundreds of total episodes), numerous films, and comic books distinct from the main DC canon created the first multimedia superhero shared universe, long before it was cool. The DCAU adapted DC Comics characters and stories with perfect precision, but it also laid the foundation for the superhero media landscape of the modern era.