The Most Difficult Hobbit Questions Finally Answered

"The Hobbit" is the first story set in Middle-earth that Tolkien ever published for the public to enjoy. Written in a simple, kid-friendly style, the book traces the journey of the unwilling adventurer Bilbo Baggins as he's dragged into a quest to help 13 Dwarves recover a hoard of wealth from the Dragon Smaug.

While the premise is pretty straightforward, as the story plays out, it reveals the vast world that "The Hobbit" is set in. (Its on-screen adaptation goes much, much further in fleshing out the peripherals of the story.) This is one of the most endearing things about the story. But it also invites a lot of confusion. As Bilbo passes through Rivendell, over the Misty Mountains, across Mirkwood, and into the Lonely Mountain, the increasing complexity of the plot leads to a lot of different questions.

We've pulled together some of the most challenging of those questions here and done our best to answer them. We say "done our best" because not everything in Tolkien's world has a clear answer. Some questions have simple responses. Others are more convoluted. But one way or another, we've found a way to finally answer some of the most difficult questions that arise from Bilbo's adventures there and back again.

Why do Dwarves seem different in The Hobbit compared to LOTR?

One of the strangest things about "The Hobbit" is the way that it presents Dwarves and Elves. The former are seen as bumbling, victimized heroes, trying to overcome impossible odds to recover their home. Sure, they're willing to send a Hobbit in to do the dirty work, but overall, Thorin and company are a fairly civil lot. In comparison, many of the encounters with Elves tend to portray them as less-than-desirable companions.

In "The Lord of the Rings," many of these opinions are reversed. Dwarves are seen as decent enough, but Elves are particularly shown in a very positive light. The author is the same in both cases. So what gives? Did Tolkien change his mind about the two races between books?

While Tolkien's world was always evolving, the answer has more to do with perspective than outright change. Each of Tolkien's books is very deliberately written. In fact, at the end of "The Lord of the Rings," Frodo literally gives a book by that name to Sam, and it's filled with his account of the story of the One Ring. The first part of the book is Bilbo's memoirs, too. And it's there that we find the big difference. Bilbo's perspective of Dwarves came from an experience where he saw their flaws, but generally was steeped in their cultural viewpoints. Frodo had some interactions with Dwarves but definitely venerated the Elves, whom he interacted with often, and the two Hobbit's perspectives shine through in their differing accounts.

Why does The Hobbit feel goofier than Lord of the Rings?

Compared to "The Lord of the Rings," "The Hobbit" is a very light-hearted story. It's silly, goofy, and family-friendly. In contrast, "The Lord of the Rings" is a serious, sad, and adult story with many themes that are far too intense for children. Again we ask, why the difference? It largely comes down to Tolkien's own evolution of who fairy tales are for.

In a letter to his publisher, Tolkien explains this, saying, "The generally different tone and style of 'The Hobbit' is due, in point of genesis, to it being taken by me as a matter from the great cycle susceptible of treatment as a 'fairy-story,' for children." In another letter written to a friend, Tolkien addresses tone again by saying that "The Hobbit," "was unhappily really meant, as far as I was conscious, as a 'children's story,'" regretfully adding that "it has some of the silliness of manner caught unthinkingly from the kind of stuff I had had served to me ... I deeply regret them. So do intelligent children."

The distinct difference in their tones is very real, and even the author was aware of the change — even if he regretted it.

What's up with Sauron's Necromancer schtick?

When Tolkien went to write a sequel to "The Hobbit," he settled on the One Ring as the connection point between the two stories. This led to a lot of character development and adjustments. Tolkien even went so far as to rewrite Gollum's character to fit the narrative. The decision also meant that the mysterious "Necromancer" character from "The Hobbit" was going to have a much bigger role. Of course, that character is Sauron, but what is he doing in Mirkwood in a ghostly, non-physical form at this point?

The answer lies in Tolkien's personal obsession with world-building. By the time "The Hobbit" was published, the author had already been working on what would eventually become "The Silmarillion" for two decades. When he wrote "The Hobbit," it wasn't supposed to connect to his then-private Silmarillion world in any particular way, but he used his personal world to infuse the nonsensical story with a sense of reality. In a letter, Tolkien says that "Mr. Baggins began as a comic tale among conventional and inconsistent Grimm's fairy-tale dwarves, and got drawn into the edge of it –- so that even Sauron the terrible peeped over the edge."

So, the initial presence of Sauron wasn't supposed to foreshadow his role as a future villain — it was just that Tolkien was writing this story in his own world. It wasn't until he decided to formally connect the stories together that he had to rectify the Sauron character with the half-thought-out "Necromancer" from "The Hobbit."

Why can the Trolls in The Hobbit talk?

Trolls are a very fascinating part of Middle-earth. In a letter, written 17 years after "The Hobbit" came out, Tolkien addresses the Troll conundrum, starting with the anything but certain phrase "I am not sure about Trolls."

There are many different versions of these underdeveloped creatures, from Hill Trolls to Cave Trolls to Olog-hai, a fierce breed of Orc-like Trolls that appear in the appendix to "The Return of the King." In that appendix, we also learn that very few of these trolls speak. It says that "In their beginning ... these creatures were of dull and lumpish nature and had no more language than beasts. But Sauron had made use of them, teaching them what little they could learn, and increasing their wits with wickedness."

In the mentioned letter, he breaks down the idea that Trolls are likely only "counterfeits" — something that Treebeard reinforces when he points out in "The Two Towers" that they're made in mockery of Ents. Further in the letter, Tolkien explains that while Trolls may be able to talk, they are much more animalistic in nature.

So ... where do the Trolls from "The Hobbit" fit in? They have very English names, are living a somewhat civil lifestyle, and, you know, they can talk. Well, it turns out that the only Trolls who are mentioned in the appendix as being particularly articulate are the Stone-trolls who "spoke a debased form of the Common Speech."

Even then, though, this is another area where Tolkien's opinions changed a lot over time — and yes, unfortunately, that means there's no solid answer.

What's up with Radagast?

For fans of "The Hobbit" trilogy, there's one character that comes across as particularly confusing. Radagast the Brown may be a wizard, but he's nothing like his tall, somber, grey-bearded companion, Gandalf. The on-screen version of Radagast (played by Sylvester McCoy) is, to put it simply, absurd. So, where does this ridiculous iteration of a wizard come from?

Well, the movie version of Radagast is nothing like the books. (Big surprise, right?) In the printed version of "The Hobbit," Radagast doesn't have a rabbit-pulled sled. He doesn't have a nest in his hair, either. In fact, he isn't in the book at all other than via an obscure reference when Gandalf tells Beorn about his "good cousin Radagast" (which isn't a literal comment regarding their family tree, by the way) to which the skin-changer replies that he's "not a bad fellow as wizards go, I believe."

While Radagast isn't in "The Hobbit" book, though, he comes up twice in "The Fellowship of the Ring," which helps us understand his character a bit better. One of those times is when Saruman derisively talks about his fellow wizard, saying, "Radagast the Bird-tamer! Radagast the Simple! Radagast the Fool! Yet he had just the wit to play the part that I set him."

Saruman's contempt is clear, and the few times that Radagast comes up, there's no doubt that he has an innocent nature. Even so, he's never the bumbling character that we see in Peter Jackson's film. He's a competent and powerful wizard, who is nothing like his preposterous on-screen interpretation.

Why do we see real giants in The Hobbit but not in Lord of the Rings?

Giants are mystical creatures, even in Middle-earth. They're mentioned throughout "The Lord of the Rings," but only in passing. In "The Return of the King," Minas Tirith is described as looking as if it had been "not builded but carven by giants out of the stones of the earth." In "The Hobbit," they're also brought up as creatures in many of Gandalf's stories, and Bilbo thinks of them as a potential answer during his riddle game with Gollum.

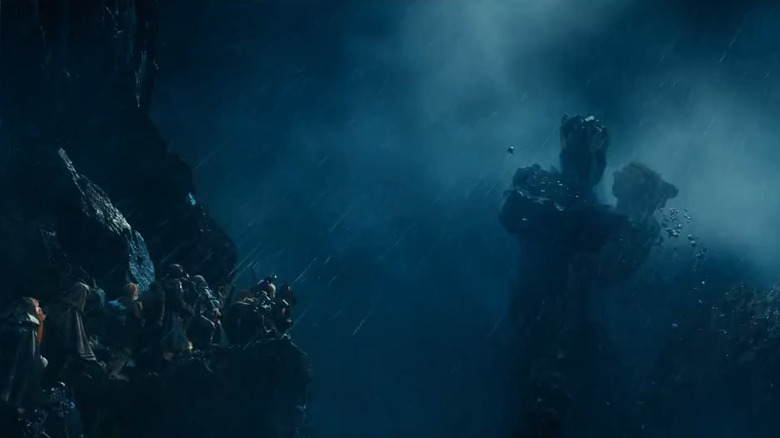

And then ... there's that time that Bilbo, Gandalf, and the Dwarves are traveling over the Misty Mountains and real stone-giants appear during a thunderstorm. The giants then start hurling rocks at each other, with the travelers caught in the crossfire. What the heck?

Get this, though: That happens in the book, too. The stone-giants cause a ruckus laughing and throwing rocks at each other ... and then proceed to never be a viable presence in anything else that Tolkien ever writes.

This one's tough, since Tolkien himself seems to have done a 180 on giants in his world. Along with the examples we already mentioned, there are many other fairly well-developed forms of giants in the earlier versions of Tolkien's legendarium. But over time, the author appears to have toned down his interest in that race, to the point where they don't feature heavily in any other areas of his writings. So, for those who love the concept of giants in Middle-earth, congratulations. They're definitely real. But if you want more giants, unfortunately, Tolkien doesn't seem to have loved them, and they play a minimal overall role in his world.

Why does Gollum like riddles so much?

Gollum is a strange creature. He lives alone, obsesses over his Ring, and loves to snack on any living thing that happens to wander near his home. So, why, when Bilbo shows up, is Gollum's first thought to start a riddle competition with his new acquaintance?

Well, first off, Bilbo has a sword, and when Gollum sees Sting he makes sure to be very polite until he figures out just who this little Hobbit is. But that still leaves the question of why riddles? Why wouldn't he just chat with Bilbo, or stalk him, or even sit there and watch him? It turns out that Tolkien answers this one via a quick, easy-to-miss line in "The Hobbit."

Just before the game starts, we read that, "Riddles were all [Gollum] could think of. Asking them, and sometimes guessing them, had been the only game he had ever played with other funny creatures sitting in their holes in the long, long ago..." This isn't just a random interest, either. Riddles are taken very seriously in Middle-earth. After the game, we learn that Bilbo "knew, of course, that the riddle-game was sacred and of immense antiquity, and even wicked creatures were afraid to cheat when they played at it." In other words, riddles aren't just a passing fancy for the peoples of Middle-earth. The formalized "riddle-game" is an event that is taken very seriously, and there's a fear of breaking the rules.

What is the origin of the Black Riders?

This question is one that any diehard Tolkien fan knows should never have to be asked in relation to "The Hobbit." While they're certainly around during Bilbo's journey, the Black Riders have absolutely nothing to do with "The Hobbit" story. Period. But nothing is sacred these days, right? And apparently, Peter Jackson and company decided that it would be fine to toss in a scene in "The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug" where they completely retcon the origin of these terrifying villains.

We're talking about the point in the story where Gandalf and Radagast stumble onto nine mysterious tombs with their occupants already resurrected and gone to meet their master in Mirkwood. The entire scene is absolutely ridiculous and doesn't jive with Tolkien's greater lore at all. The Nazgûl, led by the Witch-king, are alive and well — or at least, as alive as a wraith can be — down near Gondor at this point, ruling from their home base of Minas Morgul. While they're technically quiet during this period, they're busy preparing for their master's return to Mordor. They've also been operating all over the place throughout most of the Third Age.

So, yeah, the idea that they've been hibernating in a secret tomb is nowhere near the truth. It's also one of the most egregious changes in the entire "Hobbit" trilogy.

Where do the spiders in Mirkwood come from?

There are a lot of spiders in Tolkien's writings. They show up in "The Hobbit," "The Lord of the Rings," and "The Silmarillion" — and they're always huge. The biggest concentration of arachnids is found when Bilbo and the Dwarves pass through Mirkwood. But how did these spiders show up in the forest?

Well, it turns out that the spiders of Middle-earth aren't just numerous. They're also part of one big, unhappy family. In "The Silmarillion," we meet the first oversized monster in the form of Ungoliant. This spiritual being takes on the form of a spider, and she ends up having a lot of kids. One of those, and the last survivor of her generation, is Shelob the Great. Picking up on her mom's vile ways, Shelob carries on the family tradition by having a bunch of miserable offspring. In "The Two Towers," it explains that "Far and wide her lesser broods ... spread from glen to glen" adding that one of their destinations is "Dol Guldur and the fastnesses of Mirkwood."

When it comes to the power level of the spiders that Bilbo faces, that can be explained by the way that Tolkien scales down each generation of creatures. Ungoliant is an overpowered spiritual monster that nearly destroys Sauron's original master, the Dark Lord Morgoth. Shelob is incredibly fierce, but Samwise Gamgee is able to fight her off with a bit of luck. And her children? Well, they're so weak that Bilbo can fend off a whole hoard of them on his own ... with the help of his Ring and sword, of course.

Who on earth is Beorn?

"The Hobbit" is full of strange creatures. One oddball who is even important enough to be briefly mentioned in "LOTR" is Beorn, the skin-changer. In the "The Hobbit" — specifically, in the book — it's implied that there are many other bear-to-human creatures like him, too. What's the origin of this strange group and where do shape-shifters fit into Tolkien's world?

Unfortunately, this is another area where the author left us with little more than hints and riddles. As far as the ability to change shapes goes, that's nothing new in Middle-earth. The angelic Valar and Maiar take on physical forms all the time. In "The Fellowship of the Ring," Gandalf describes Radagast as "a master of shapes and changes of hue." Even Sauron turns into a werewolf, a serpent, and a vampire bat in "The Silmarillion."

But for all the shifting and changing, Beorn's specific race of skin-changers remains extremely mysterious. All we get is Gandalf's initial description of the fellow in "The Hobbit," which reads, "Some say that he is a bear descended from the great and ancient bears of the mountains that lived there before the giants came." The wizard adds that "Others say that he is a man descended from the first men who lived before Smaug or the other dragons came into this part of the world, and before the goblins came into the hills out of the North." While the wizard isn't sure, he favors the second option. But, as he himself also says about the matter, "I cannot tell you much more, though that ought to be enough."

How is Bilbo so lucky?

One of the strangest things about "The Hobbit" is its apparent obsession with lucky incidences. This can be somewhat seen in the movies. Bilbo survives an encounter with Smaug. He outsmarts Gollum. Oh yeah, and he finds the One Ring when he's blindly crawling through a subterranean tunnel. One way or another, everything seems to go right for this guy. This is even more blatant in the book, where luck is constantly referenced. For instance, when Bilbo guesses which way to go in Mirkwood, it says that "by luck (he was born with a good share of it) he guessed more or less right ..." Later on, in the Wood Elves' caves, it adds that "Luck of an unusual kind was with Bilbo then."

Why the constant references to luck? It turns out that Tolkien brings it up specifically to underline that, well, it isn't luck at all. At the end of the book, Gandalf literally tells Bilbo, "You don't really suppose, do you, that all your adventures and escapes were managed by mere luck, just for your sole benefit? ... you are only quite a little fellow in a wide world after all!"

This purposefulness and intentionality is emphasized in the commentary written by the "Tolkien Professor," Corey Olsen, in his book "Exploring J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit." Olsen describes this recurrent luck by saying "There is a larger plan or higher destiny at work behind these strokes of fortune ..." The fact that Tolkien was a Catholic who believed in a Creator certainly backs up these sentiments.

Is there a Dwarven Ring in the Lonely Mountain Treasure Hoard?

If you've read "The Hobbit" and "The Lord of the Rings," it's hard not to hear about all of this treasure talk and wonder "is one of those Seven Dwarven Rings involved?" After all, we get the Arkenstone, which is a super-jewel with its own inner power. "The Silmarillion" also explains that "the foundation of each of the Seven Hoards of the Dwarf-kings of old was a golden ring; but all those hoards long ago were plundered and the Dragons devoured them..." This seems like a surefire recipe for the Lonely Mountain hoard to be one of those seven hoards. So, is there a Dwarven ring lying at the heart of the mountain? Or possibly in Smaug's belly?

Well, it turns out that the answer is no, but also ... kind of.

See, the Lonely Mountain is founded by part of the group of dispossessed Dwarves who are driven out of Moria by the Balrog. Long before that point, one of their kings receives one of the Seven Dwarven Rings and it stays in the family until Thorin's father loses it when he's captured by the Necromancer. So, while there isn't a Dwarven Ring present when Bilbo arrives on the scene, one of the Rings of Power is likely responsible for the massed wealth that he finds Smaug using as a bed.

What's with Eagles saving the day ... again?

It doesn't take much to notice that the Eagles play an important role throughout Tolkien's world. They save Bilbo, Gandalf, and the Dwarves from the clutches of the Orcs of the Misty Mountains. They show up to help turn the tide during the Battle of Five Armies. Their leader, Gwaihir the Windlord, saves Gandalf when he's trapped on Orthanc — and his Eagles swoop in to join in the fight in front of the Black Gate at the end of the story, too. Eagles also save the day multiple times during "The Silmarillion." So ... what's up with the Eagles always arriving in the nick of time? Is it a cop-out? Is it a lazy excuse to resolve a story?

Nope. Tolkien's use of things like the Eagles to provide dramatic savior-like moments is something that the author specifically developed. In fact, he coined a term for the activity. He called it a eucatastrophe. In Tolkien's famous essay "On Fairy Stories," the author points out that, while drama and tragedy go hand in hand, fairy stories must come with a consolation or happy-ending.

In a letter written to his son, Christopher, the author defines the concept of a eucatastrophe as "the sudden happy turn in a story which pierces you with a joy that brings tears (which I argued it is the highest function of fairy-stories to produce)." When writing fantasy, Tolkien felt it was a primary function of the story-telling format to provide these moments of grace and salvation, and doing so with the majestic Eagles remained one of his favorite ways of implementing this concept for his entire life.