The Untold Truth Of Planet Of The Apes

The Planet of the Apes franchise has appeared dead and buried on more than one occasion over the course of its near-50 year existence. But the impact and long lasting influence of the 1968 original has always prompted 20th Century Fox to keep the property going. However, after Tim Burton's 2001 remake killed that particular franchise relaunch, studio execs went back to the drawing board. And a decade later, they finally cracked it.

Beginning with 2011's Rise of the Planet of the Apes and apparently ending with 2017's War for the Planet of the Apes, the prequel trilogy has been a runaway success, lauded by critics and raking in over a billion dollars worldwide and counting. But while it's great to see one of Hollywood's best-known sci-fi franchises delivering the goods again, the history of Planet of the Apes has seen so many ups and downs, there was once a chance this would never happen at all.

The author of the original novel was a former spy

Late French novelist Pierre Boulle has been described as "profoundly Anglophile" by Jean Loriot of the Association of Friends of Pierre Boulle (quoted by the BBC in a profile on the author). During the 1930s, Boulle worked for a British rubber planting firm in Malaysia and during that time he fell in love with the English way of life — so much so that he would eventually join the South East Asian branch of the Special Operations Executive, set up by the UK government to conduct espionage and sabotage in the region during World War II.

The BBC quotes him explaining his work with the SOE: "Serious gentlemen taught us the art of blowing up a bridge, attaching explosives to the side of a ship, derailing a train, as well as that of dispatching to the next world — as silently as possible — a night-time guard."

If any of that sounds familiar, it's probably because you've seen The Bridge on the River Kwai. Published in 1952 and adapted into a critically acclaimed feature film in 1957, Boulle's third novel was inspired by his own harrowing experience as a prisoner of war. After being captured while undercover in Vietnam, the Frenchman was sentenced to hard labor for life, but escaped after two years of captivity. When the war ended, Boulle began writing novels. In 1963 he published La Planète des Singes, translated into English in 1964 as Monkey Planet and later reissued under the title Planet of the Apes.

The twist ending wasn't in the book

Charlton Heston's discovery of the ruined Statue of Liberty in the original Planet of the Apes is one of the most iconic movie twists of all time, though it didn't come from the source material. Boulle didn't class his novel as a sci-fi ("science fiction is only the pretext," he told Cinefantastique magazine back in 1972) and this was abundantly clear to Rod Serling, the first screenwriter to work on adapting it for the big screen.

"As talented and creative a man as Boulle is, he does not have the deftness of a science fiction writer," Serling also told the horror and sci-fi magazine. "Boulle's book was a prolonged allegory about morality more than it was a stunning science fiction piece. But it contained within its structure a walloping science fiction idea."

According to Serling, a "nickel-and-dime" outfit named The King Brothers first approached him about writing a screenplay for Planet of the Apes, though the rights to the property eventually wound up in the hands of producer Arthur P. Jacobs. Together, the pair came up with the famous Statue of Liberty ending and included it in the draft they ultimately took to 20th Century Fox. The studio approved, but the original author did not.

"I disliked somewhat the ending that was used, which the critics seem to like," Boulle said. "But personally, I prefer my own." The twist in the novel is that the couple narrating the main story about a human stranded on a planet inhabited by apes were actually chimpanzees themselves all along.

It saved Fox from bankruptcy

Fox was in a tight spot in the mid-1960s after having spent $44 million (the most ever thrown at a motion picture at the time, according to The Guardian) on 1963's Cleopatra, a film remembered today as one of the biggest turkeys in Hollywood history. Despite being the highest grossing film at the box office that year, it still lost huge amounts of money thanks to extensive re-shoots, leaving the studio facing bankruptcy. If Planet of the Apes was to be their comeback, they couldn't afford to make the same mistakes.

With that in mind, Serling re-imagined the ape society as a "semi-primitive, semi-civilized" one (in his first draft they lived in an advanced, New York-like metropolis) and this cut budget requirements drastically. Jacobs then brought in previously blacklisted writer Michael Wilson to rewrite the dialogue, which Serling later admitted was the right move. "Mine was a much more sombre and serious dialogue," he said. "Wilson used a lot of puns and juxtaposed familiar expressions... I gather the humor was one of the key reasons for the success of the picture."

Fox finally signed off on a $5.8 million budget and would see a nice return on that investment. "Planet of the Apes equals gargantuan box office," The Hollywood Reporter said in their 1968 review, and they were right. While it earned less than Cleopatra ($33 million versus $58 million), it was made for a fraction of the cost.

They hired every makeup artist in Hollywood

Planet of the Apes was huge for Fox, but it could've been a different story had a rival studio known how to handle the property. In 1965, Jacobs told Variety that it would be Warner Bros. backing the adaptation. But after early makeup, costume, and art direction tests failed to inspire, there were lengthy delays. After over 18 months with no movement, Jacobs teamed with Fox instead.

Once he had the greenlight, Jacobs hired every available makeup artist in Hollywood, which still wasn't enough. "There weren't enough makeup men in Hollywood so we had to train them," the producer revealed to Variety. "We had 10 trailers that were turned into classrooms for makeup." In the end, $1.5 million went on makeup, making it the biggest single expense on the film. Jacobs also said getting the apes to look so convincing didn't just cost money, but precious time also.

"It took three to four hours to put [the makeup] on every day and about an hour and a half to get it off," he said. "Applying and removing it used up almost 60 percent of our total shooting time." It was a necessary evil according to Serling, however, who knew that the biggest problem the film faced was creating realistic apes. "The whole thing was to make an audience believe it and take it seriously," he told Planet of the Apes Magazine in 1975.

It pioneered the Space Opera genre

According to leading man Charlton Heston, Planet of the Apes pioneered a genre of film most commonly associated with Star Wars movies today. "It not only grossed enormous numbers, it created a new film genre: the space opera," he said in his autobiography In The Arena. "Fantasies set in outer space had long been a staple of the comic strips and Saturday morning kiddie TV, but had been disdained by Hollywood. Later, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas were to explore space wonderfully, with far better technology, over a series of films, but Apes broke the ground."

While the makers of the Flash Gordon film serials of the 1930s would probably dispute Heston's claims that Planet of the Apes was the first big screen space opera, nobody could argue with the figures. Ironically, those "enormous numbers" Heston spoke of were down to the fact that Planet of the Apes appealed to both the Saturday morning kiddie TV crowd and the adult audience, too.

Maurice Evans, who played Dr. Zaius, told Cinefantastique, "I think it's pretty clear, whether by design or accident, the first picture had this double appeal. The appeal to youngsters [was] as a pure science fiction film, but it had a message to deliver which apparently communicated very clearly to the adult audience."

Fox wanted more of the same for less money

Fox wasted little time in developing a Planet of the Apes sequel. Pierre Boulle was consulted, turning in a treatment called Planet of the Men in which the enslaved humans stage a rebellion to reclaim Earth for mankind. It was his first experience with screenwriting, however, and his script wasn't considered cinematic enough. "After the success of the first film, Arthur Jacobs requested that I do a sequel for him," Boulle said. "They accepted the treatment that I worked on, but they made so many changes that very few of my ideas were left."

As was the case with the first movie, Fox wanted to keep costs as low as possible. The studio brought in new writers and greenlit a sequel and three prequels between 1970 and 1973: Beneath the Planet of the Apes, Escape from the Planet of the Apes, Conquest of the Planet of the Apes, and Battle for the Planet of the Apes. And the studio offered a less attractive production budget each time. Battle did see a small increase of $100,000 on its predecessor's budget, but like all the early sequels and prequels (with the notable exception of Escape) it was panned by critics.

The TV adaptations flopped

According to revelations from the tell-all documentary Behind the Planet of the Apes (obtained via Ain't It Cool), Jacobs had always intended to take the franchise to television. When he died in 1973, the rights went to Fox, and they fulfilled the late producer's wishes. CBS had reported massive viewing figures when they aired the first Planet of the Apes movie in its television debut, so they struck a deal to develop a TV spinoff. Roddy McDowall (who appeared in four of the five movies as different characters) returned to play yet another chimp, but the show's limited budget meant it lacked the sweep of the films and it was axed before the fourteenth and final episode aired.

Next to partner up with Fox was NBC, which wanted to try Apes as a Saturday morning kids show. "It was a potential godsend," Den of Geek said after revisiting the cartoon, which debuted in 1975. "People loved the apes, but were tired of seeing them tromp around unused Western sets, brandishing outdated rifles and having fistfights in barns. That was all the budget allowed for live action, but with a cartoon the sky was the limit." Or so the creators thought.

A clause in the contract meant Doug Wildey (in his debut — and farewell — as a director) was forbidden from including violent actions that could be imitated by children, meaning that no guns or knives were permissible. Just like the live action series, it was pulled after 13 episodes.

Tim Burton's reboot was originally a sequel

The reboot Tim Burton wound up directing in 2001 was first conceived way back in 1988 when Fox president Craig Baumgarten saw a movie called Never on Tuesday by a young filmmaker named Adam Rifkin. He invited Rifkin to pitch any ideas he had to Fox, and he told the studio he wanted to do a new Planet of the Apes sequel starring either Tom Cruise or Charlie Sheen. Using James Cameron's Aliens as an example, Rifkin said he could offer them a quality sequel without breaking the bank.

"Having independent film experience, I promised I could write and direct a huge-looking film for a reasonable price," he is quoted as saying in David Hughes' Tales From Development Hell (via Wired). But as time ticked on (and Baumgarten left Fox) Rifkin was phased out. Sam Raimi's name was linked briefly, but the project really picked up steam again in 1993 when Oliver Stone became attached.

According to Hughes' book, disagreements over the screenplay rumbled on and eventually Stone pursued other projects. Chris Columbus (who shot some "pretty ludicrous" tests of apes skiing according to one-time producer Don Murphy) came and went, and James Cameron even considered the job before Tim Burton was finally hired in 2000. Burton said that he was excited about the idea of "re-imagining" the Planet of the Apes mythology, as opposed to doing a sequel as Rifkin originally intended.

Burton blasted the studio

When Burton's so-called re-imagining finally hit cinemas in 2001, it failed to live up to the wait. On paper it looks like an undeniable hit — it went on to earn over $360 million at the worldwide box office. But critical opinion has always been at odds with the figures. The Hollywood Reporter ranked it rock bottom in a list of Burton's films, claiming that his "effects-driven reboot lacks the originality and cult appeal of its 1968 blueprint," and veteran film critic Roger Ebert agreed. "Ten years from now, it will be the 1968 version that people are still renting," he said.

But Burton was happy with the finished product, despite the criticism of the movie's nonsensical ending. When asked by The Guardian what he would do differently if he had the chance to go back and do Planet of the Apes all over again, the director responded angrily, placing the blame for the film's failings directly at the studio's door. "Here's what I'd do differently, give the f***ing green light at the goddamn beginning so we're not spinning our wheels for six months where there is no positive work being done," he said, before confirming that he would not return for a sequel. "The idea of me doing [another], I'd rather jump out the window. I swear to God."

Fox pushed for an Oscar nomination for Andy Serkis

When Roger Ebert said that it would be the 1968 version of Planet of the Apes that people would be renting in ten years time, he didn't know that a brand new version would be making headlines a decade after his review. Screenwriters Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver began working on what would become Rise of the Planet of the Apes in 2005, inspired by a news story about a chimp raised in a human household.

The film was a critical and commercial success, and a lot of that was down to a brilliant performance by Andy Serkis, who brought protagonist Caesar to life through motion capture. Serkis had already played a famous CGI monkey in Peter Jackson's 2005 remake of King Kong, and of course was an essential part of the director's The Lord of the Rings films as Gollum. Fox decided he was overdue some recognition and campaigned for an Oscar nomination in the Best Supporting Actor category.

It never happened, but Serkis himself recently brought the motion capture performance debate back to the table, telling Independent that they are just as worthy of Academy recognition as live action ones. "The awarding bodies should not discriminate about this being different," Serkis said. "The visual effects render the character, just like putting on makeup, except here it happens after the fact. It's digital makeup, if you will."

The rebooted series is full of Easter eggs

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes followed in 2014, with Matt Reeves coming on board to replace outgoing director Rupert Wyatt. The sequel proved an even bigger success than the previous film, raking in a mammoth $710 million worldwide and delighting critics. The third installment, War for the Planet of the Apes, has similarly hit with critics, and topped Spider-Man: Homecoming during its opening weekend. After a turbulent few decades, the rejuvenated franchise is finally in a strong position again, and one of the great things about the new movies is that they still recognize where they came from.

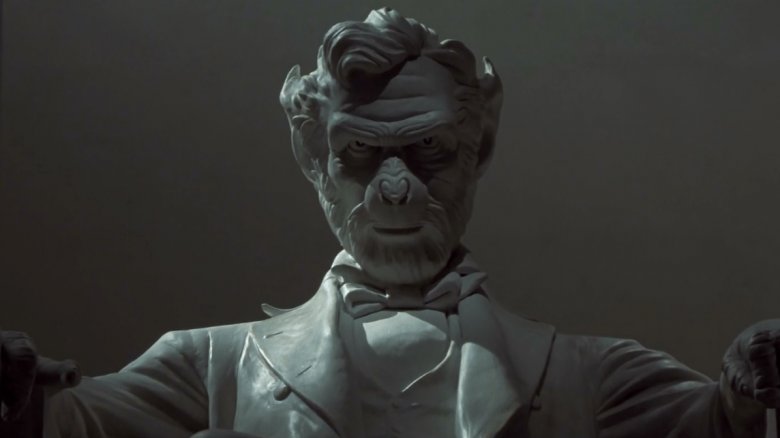

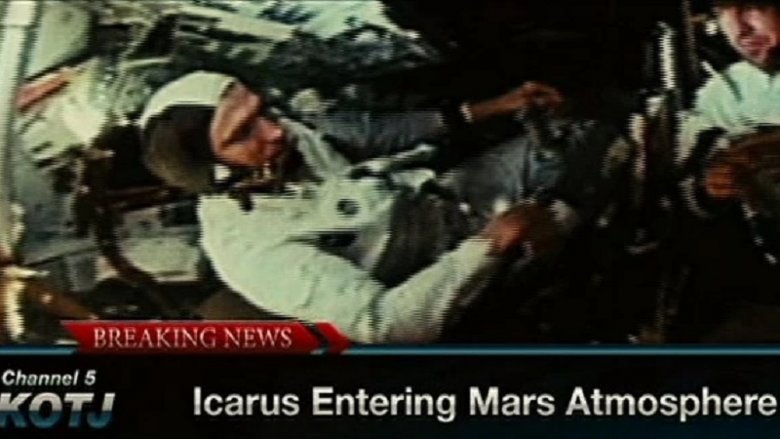

The first two films in the rebooted series are full of Easter eggs and nods to the original. They slipped in a toy Statue of Liberty, quietly shot George Taylor (Charlton Heston) into orbit aboard Icarus, and even lifted full lines of dialogue from the 1968 version, which was a bone of contention in the board room. "There were some fights about that one," producer Dylan Clark told Coming Soon from the set of War for the Planet of the Apes, which also contains nods to the previous entries. "There are certain characters and certain things that you will see in this movie too, so again we pay some homage, some of it is just cool for the mythology."

Are all the films connected?

As it turns out, Clark was downplaying just how much War for the Planet of the Apes would fall in line with the earlier films. Caesar's infant son makes an appearance, who we discover is named Cornelius — the same name as the ape that helped Taylor escape captivity in the 1968 original. Cornelius' son (and presumably Caesar's grandson) would later take on the name Caesar in 1971's Escape from the Planet of the Apes.

Outside of Caesar's family, War for the Planet of the Apes introduces a mute human girl named Nova, who fans of the original movie will remember as Taylor's fully grown (and scantily-clad) companion. The reason behind Nova's inability to speak in anything but grunts does differ in the new movies (simian flu is now to blame), but the filmmakers seem to be willing to overlook that in order to tie the whole franchise together in a timeline, which is likely why they included the launching of Taylor's spacecraft in the background.

Icarus might have to wait a little while to crash land, however, as Matt Reeves told Gizmodo that "there are many more exciting stories to be told" in the Planet of the Apes universe. Stay tuned for more monkey business sooner rather than later.