Bizarre And Disturbing Black-And-White Horror Movies That Scared Audiences

Black-and-white horror films aren't scary, are they? That's the prevailing attitude among some horror fans and some filmgoers in general: if it's in black-and-white, it's boring and out-of-date, with corny plots, over-the-top acting, and ridiculous special effects. Who today could possibly be scared by Bela Lugosi's Dracula or Boris Karloff's Frankenstein Monster, who terrified moviegoers in 1931? And while it's true that the fears summoned up by these classic titles may have been slightly blunted over time by more graphic horror fare, there are still plenty of black-and-white horror films that can stir the blood and raise the hairs on the neck of modern audiences.

Some of these films screened around the same time as "Frankenstein" and "Dracula" and took advantage of looser restrictions on movie subject matter prior to the establishment of the Motion Picture Production Code, which reined in depictions of sex and violence in 1934. Others were made in the mid-20th century and took advantage of the low cost of black-and-white film to accommodate their limited budget, while others adopted black-and-white to lend an otherworldliness to their stories and images.

In all cases, these horror films proved that color wasn't the defining factor in what made a movie scary. Following are some of the most notable examples of weird, otherworldly, and disturbing black-and-white horror films that terrified audiences over the last hundred years.

Spoilers will definitely follow.

Häxan

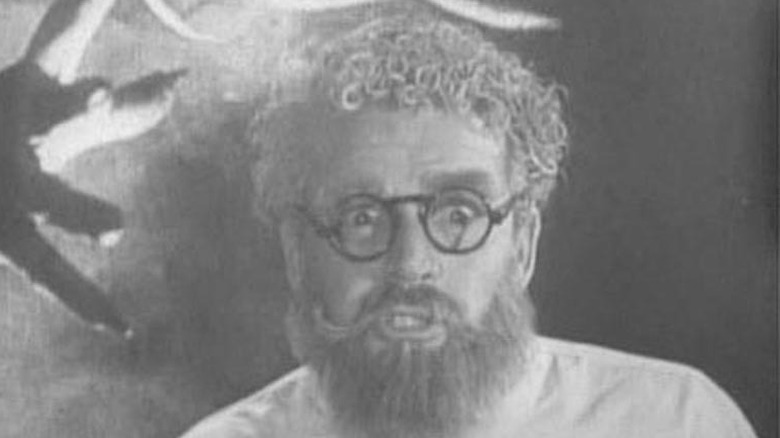

If you don't believe that silent films have the power to shock and surprise, then it's time that you see "Häxan." The 1922 Swedish film — also known as "Witchcraft Through the Ages" — used what would be considered rudimentary visual effects by modern standards to depict medieval beliefs in the supernatural and witchcraft and how they led to the deaths of countless individuals who may have been suffering from untreated mental illnesses.

Director Benjamin Christensen pulls out all the stops available to filmmakers before the dawn of talking pictures, from stop motion animation and superimposition to elaborate makeup and in-camera effects to suggest extraordinary scenes of black magic and witchcraft, including nuns desecrating a consecrated host and a surprisingly graphic (for the time) Witches Sabbat, with accused spellcasters cavorting with actors in elaborate demon makeup and committing obscene acts with Satan, who is played with relish in the film by Christensen himself.

The Black Cat

It's not just the presence of Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi that makes the 1934 supernatural thriller "The Black Cat" so alarming. Nor is it the striking, Bauhaus-inspired production design, or director Edgar G. Ulmer's use of shadow and camera angle, on which he received a world-class education while working with, among others, "Nosferatu" director F.W. Murnau, in Germany during the 1920s (via Britannica).

What makes "The Black Cat" so disturbing to modern viewers is its shocking suggestions of violence. The film — which pits Satanist Karloff against Lugosi's doctor, whose experience as a POW under Karloff has put his sanity in check — makes barely-concealed allusions to, among other deviant actions, torture, mass slaughter, and necrophilia involving Lugosi's dead wife and Karloff, who also carries on a wholly inappropriate relationship with his zombified stepdaughter.

None of these horrors are shown in any sort of graphic detail. But "The Black Cat" does creep close to gruesome territory in its final scene: Lugosi, having broken up Karloff's attempt at a human sacrifice during a Black Mass, finally loses the last of his marbles and chains Karloff to a rack before skinning him alive. The only possible conclusion to such an orgy of insanity is the total destruction of Karloff's house of horrors, triggered by Lugosi, who utters with his dying breath, "It has been a good game."

Doctor X

In Warner Bros' 1932 chiller "Doctor X," murder most disgusting has been committed — multiple times. A maniac known as The Moon Killer stalks New York City, slaying and partially devouring victims during the full moon. The police turn to Doctor Xavier (Lionel Atwill), ostensibly to solve the crimes, but also to investigate the decidedly offbeat staff of his clinic (which includes a voyeur and a cannibalism expert). Xavier's solution is to wire each of his doctors to a heart monitor and re-create the murders (!) before them, with the idea being that the sight of the killing will elevate the guilty party's heartbeat. This out-to-lunch scheme doesn't flush out the Moon Killer — who shows up on his own to reveal his gross reasons for collecting the flesh of his victims.

"Dr. X" was Warner's second film to use its improved Technicolor process (which, while not totally black-and-white, only used two colors), and was such a hit at the box office that the studio re-teamed director Michael Curtiz ("Casablanca") and stars Lionel Atwill and Fay Wray in "Mystery of the Wax Museum." They also issued a sequel, "The Return of Dr. X," with Humphrey Bogart playing a different mad doctor who needs synthetic blood after being brought back to life.

Murders in the Rue Morgue

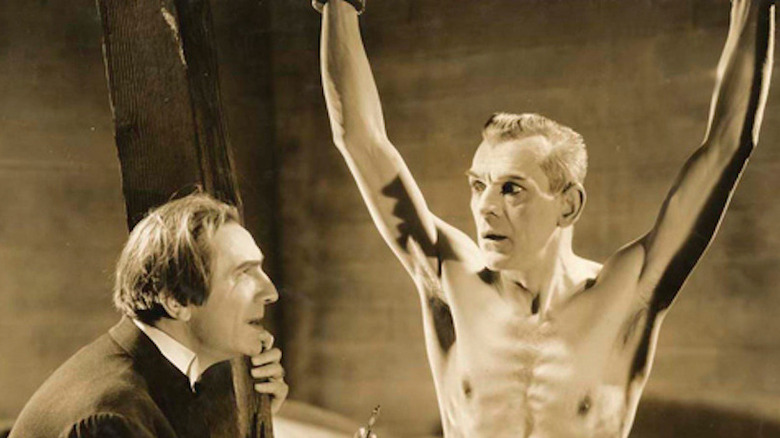

Two years before shocking audiences with "The Black Cat," Bela Lugosi waded into morbid waters with 1932's "Murders in the Rue Morgue." Director Robert Florey's film shares just two elements with the Edgar Allan Poe story on which it's based — a rampaging ape and the fate of one of its victims — and instead runs riot with a plot involving mad scientist Dr. Mirakle (played by Lugosi), who has some curious (read: gross) ideas regarding evolution.

Mirakle is obsessed with the idea of mingling apes and humans — all the better to provide a mate for his gorilla, Erik (Charles Gemora), whom he features in a sideshow presentation. Since Mirakle's science is, at best, questionable, he's forced to abduct human test subjects from Paris's population of working girls, whom he puts through various tortures, including a full-blown crucifixion, before injecting them with Erik's blood (!) in order to, well, the end result isn't entirely clear, but it does leave the victims deathly ill, but makes Erik very excited.

"Murders" is a classic example of "pre-Code" Hollywood filmmaking, which spurred the industry to police itself with the Hays Code' restrictive edicts on subject matter. Lugosi would go on to play many more mad scientists in his tumultuous film career, but perhaps none as totally deranged as Dr. Mirakle.

Mad Love

Obsession fuels much of the macabre goings-on in "Mad Love," a 1935 psychological thriller with Gothic trappings and buckets of perverse psychology. Karl Freund, who served as cinematographer on many early German horror and science fiction classics like "The Golem" and "Metropolis," made his final turn as director (after helming "The Mummy" for Universal) on this MGM chiller, which marked the American film debut of his countryman, actor Peter Lorre.

Lorre, who had risen to fame in Germany with a disturbing portrayal of a child murderer in Fritz Lang's "M," was the perfect choice to play the film's antagonist, Dr. Gogol. A brilliant surgeon, Gogol is also a raving maniac with an unholy fixation on Frances Drake and especially her torture victim role in a Grand Guignol-style stage production. When her pianist husband (Colin Clive of "Frankenstein") loses his hands in a train accident, Gogol seizes upon a deranged way to win her love: he transplants the hands of a murderer onto Clive, who immediately picks up the former owner's penchant for knives.

Lorre, who spends much of the film giggling madly or fondling a wax statue of Drake, pushes "Mad Love" into nightmare territory in a scene where he attempts to convince Clive that he is the murderer from whom he obtained the killer hands: sheathed in a metal bodysuit and neck brace, Lorre's Gogol looks like a steampunk prototype for the body horror that David Cronenberg brought to life several decades later.

Lash of the Penitentes

Los Hermanos Penitentes, or the Penitente Brotherhood, is an obscure lay society associated with the Catholic Church for more than 400 years. Elements of the brotherhood have practiced ritual mortification, including symbolic crucifixion, in the past, which is still practiced by other religious groups to varying degrees today. The 1936 exploitation feature "Lash of the Penitentes" mixes real documentary footage of the penitentes' practices with a lurid dramatic storyline based in part on a real-life murder case allegedly linked to the sect.

The documentary footage, shot by cinematographer Roland Price, shows penitentes crossing the harsh desert terrain of New Mexico while carrying enormous crosses or being whipped by fellow members. It's harrowing to watch, even by modern standards. The wrap-around story, based in part on a 1936 case involving writer Carl Taylor, who was murdered while researching the penitentes, is cheaply done and leans heavily on footage of a female penitente being whipped sans clothing.

Maniac

Actor Bill Woods chews the scenery in 1934's "Maniac" as Don Maxwell, an actor on the skids and in the employ of Dr. Meirschultz (silent film actor Horace Carpenter), a certifiably insane medico obsessed with bringing the dead back to life. When Maxwell bungles the theft of a body from the local morgue, Meirschultz demands that he step in as the corpse du jour; Maxwell instead kills his boss and, for reasons known only to him, disguises himself as Meirschultz to continue his work.

What follows is a loosely connected series of vignettes that illustrate how Maxwell's already tenuous grip on reality becomes fully hands-off after he impersonates Meirschultz. After walling up the dead doctor (the first of many allusions to Edgar Allan Poe in the film), Maxwell injects a patient seeking psychological help with an unknown chemical, which turns him into a raving lunatic; he then pauses briefly to pry out and eat the eye of Meirschultz's cat before pitting his own duplicitous wife against the nutzoid patient's spouse in a syringe fight. "Maniac" lurches to a conclusion inspired by "The Black Cat," with Maxwell raving that the mutilated cat has given away the location of Meirschultz's body.

Produced and directed by exploitation pioneer Dwain Esper ("Reefer Madness"), "Maniac" revels in flaunting Production Code taboos and delivering a barely coherent story lashed together with flashes of nudity, bizarre behavior, and gross-out moments (as well as clips from "Häxan"). To avoid attracting negative attention, some prints of "Maniac" featured wrap-around segments which claimed that the film was a sort of primer for various forms of mental illness.

Dementia

"Dementia," which began life as a surreal 10-minute short by filmmaking hopeful John J. Parker, bloomed — though maybe "spread" (as in a virus) is a better term — into a feature in 1955 and has baffled and alarmed viewers ever since. The film was inspired by a nightmare experienced by Parker's assistant, Adrienne Barrett, whom he cast as the lead in the finished project. The film itself unspools without dialogue and follows a young woman who traverses a nightmarish city on a vague mission to exorcise her family demons — Dad killed Mom, and the girl killed Dad — by committing another murder. That occurs, after a fashion, but the line between reality, fantasy, and fear leaves the viewer wondering if she's carried out a crime or not.

Largely improvised by a cast and crew composed of non-professionals (Barrett) and veterans (Roger Corman veteran Bruno VeSota, composer George Antheil, and DP William Thompson, who also worked with Ed Wood and shot "Maniac"), "Dementia" was soundly rejected by the New York State Censor Board, which deemed it "inhuman" and "indecent" (via TCM). Parker later sold the film to producer Jack H. Harris, who re-edited the film, added a new title ("Daughter of Horror"), and leering narration by a then-unknown Ed McMahon. Harris later added footage from "Dementia" into his most famous production – "The Blob."

Time hasn't dampened the threadbare eeriness of "Dementia," though critics have come to appreciate Parker's direction, deeming it a one-of-a-kind hybrid of exploitation and surrealism.

Eyes Without a Face

A father goes to terrible extremes to express his love for his daughter in French director Georges Franju's haunting 1960 film "Eyes Without a Face." The dad in question is Pierre Brasseur's Dr. Gennesier, a dedicated surgeon whose daughter (Edith Scob) has been disfigured in a car accident. Determined to repair the damage — which Scob hides beneath a pale white mask — Gennessier and his assistant (Alida Valli) kidnap young women and transplant their faces onto his daughter, who remains unaware of her father's actions.

Though "Eyes" features a brief and heart-stopping surgery sequence, the film's horror is filtered through an atmosphere of suffocating sadness and surreal imagery. The doctor's actions, while monstrous, are motivated by care for his daughter, who drifts through the film like a ghost. That people have to die horribly to repair the damage they suffer only adds to the gloom that hangs over "Eyes" like a shroud.

"Eyes" made a commotion in Europe during its release, with audience members fainting during the surgery sequence. It received mixed reviews from critics and came to America in a truncated version titled "The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus." But like "Dementia," the film developed a following that led to a reappraisal of Franju's film as a true horror classic. It's also served as inspiration for countless other creative types, from Spanish exploitation director Jess Franco's surgical horrors ("The Awful Dr. Orlof") to the mask worn by Michael Myers in "Halloween" (and yes, the Billy Idol song of the same name).

Carnival of Souls

In 1962's "Carnival of Souls," an ill-advised race on a rickety Kansas bridge sends motorist Mary (Candace Hilligoss) to what seems like a watery grave in the river below. But she somehow emerges unscathed and begins a new life as a church organist in a remote town. Her happiness, however, is constantly impinged by the sense that something isn't right — could it be the visions of the Man (director Herk Harvey), a ghostly, beckoning figure. It seems to hinge around an old pavilion outside town (the real-life Saltair Pavilion in Salt Lake City, Utah), where Mary discovers the truth about her place among the living — and the dead.

Harvey, who directed "Souls" over the course of three weeks, displays a talent for arthouse-quality images that were unseen in his day job as an industrial filmmaker. Many of its sequences — especially the finale, set in the ruined pavilion — retain their power to chill more than six decades after its release. The film, however, dropped out of sight shortly after its release and remained, for many viewers, almost a figment of their imagination, a dimly remembered lucid nightmare from late-night TV. A 1989 restoration and re-release did much to revive interest in and appreciation for the film, which is now part of the Criterion Collection.

November

Magic – both helpful and malevolent – is not only real but an everyday occurrence in the remote 19th century Estonian village that serves as the setting for writer-director Rainer Sarnet's 2017 film "November." The hamlet, which seems to be stuck, at least in terms of progress, in the Middle Ages, is home to not only the ghosts of the dead, but also various supernatural creatures. These include the kratts, creatures assembled from various animal and mechanical parts, but also two embodiments of the plague, a witch, and finally, the Devil himself.

Sarnet's film — which also concerns a pair of young villagers in love — treads the line between fairy tale and horror and frequently dips fully into one genre or another for extended periods of time. It's also quite amusing, though any lightness of mood is usually dispelled by Mart Taniel's starkly beautiful photography and the score by Jacaszek, who unleashes a Eastern European take on Ennio Morricone's eclectic soundtracks, freely mixing animal howls, electronic moans, and sheets of guitar noise.

The Addiction

Blood is a drug that can't be kicked in Abel Ferrara's gory, gloomy 1995 indie "The Addiction." Lili Taylor stars as a New York graduate student whose encounter with vampire Annabella Sciorra leaves her with an insatiable appetite for blood. She preys on strangers and friends alike, including classmate Edie Falco, while struggling with overpowering guilt from her actions. A fellow vampire (Christopher Walken) attempts to school her on breaking the habit, but the pressures of academia push her over the edge, and she upends her life and future in a wall-to-wall orgy of blood.

"The Addiction" works as a grisly extended metaphor for the horrors of drug addiction, as described by Filmmaker: Taylor steals blood from her victims with a syringe, suffers from an overdose, and ruins the lives of everyone around her with her inescapable thirst. The spiraling shame associated with addictive behavior is also explored in detail, and Ferrara puts quotes from various philosophers into the mouths of his characters to help explain suffering and lapsed morals. So much emotional heaviness might ward off most horror fans, but Ferrara wisely keeps the spatter flowing throughout the film, especially in its gruesome finale.

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

The Eyes of My Mother

Horror begets horror in director Nicolas Pesce's 2016 indie "The Eyes of My Mother." The thriller concerns Francisca (Kika Magalhaes) who, having witnessed her mother's brutal and senseless murder as a child, revisits the trauma upon everyone unlucky enough to cross her path an adult. The queasy joke hidden in the title should serve as fair warning to anyone who gets squeamish about eye trauma.

Though horrible mutilation is visited upon a number of innocent people in "Eyes," Pesce's film isn't just a catalog of cruelty. It instead focuses its stark-toned camera eye on the impact of violence — how it stains everyone and everything it touches, turning emotion and intent into hideous parodies of themselves. Francisca suffers terrible pain, but also uses it to soothe her emotional damage, which only twists and warps her ideas about love, family, and motherhood.

The violence in "Eyes" was enough to drive some moviegoers out of screenings when it played Sundance in 2016, but one wonders if the monstrous family that Francisca tries to build had something to do with it, too.

The Lighthouse

A story of madness, sea monsters, and mythology, interspersed with copious drinking and intestinal gas, Robert Eggers' 2019 freakout "The Lighthouse" proves that black-and-white can spin heads as well as any full-color fear fare. Robert Pattison and Willem Dafoe give no-holds-barred performances as a mystery man who takes a job at a remote lighthouse, and the salty keeper of the structure, respectively; the pair embody the darkest, furthest depths that loneliness and terror can bring out in us with a fury that is at times difficult to watch.

According to the Los Angeles Times, Eggers shot "The Lighthouse" in black-and-white in order to suggest photographs from the 19th century, which is when the film takes place. He also used extremely low light and an out-of-date aspect ratio (1:19:1), which cramps the frame to the point of near-claustrophobic — all the better to underscore the cauldron of psychological turmoil that boils under every scene. As with "Maniac," animal lovers — especially those with a fondness for birds — should be forewarned that Pattison holds a serious grudge against a one-eyed seagull in the film.