What Star Trek Fans Might Not Know About Gene Roddenberry

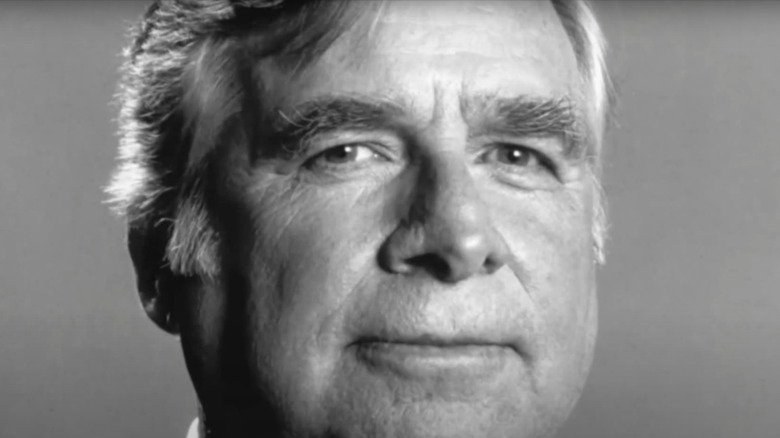

2021 marks the 55th anniversary of the original "Star Trek," the unkillable pioneer of science fiction television that became a global phenomenon and changed the entire notion of fandom forever. Fittingly, August 19th, 2021, would have been the 100th birthday of Gene Roddenberry, the show's creator, and on that day, Roddenberry Entertainment announced that it would be producing a biopic about the man known to "Trek" fans as "the Great Bird of the Galaxy." At long last, the story of Roddenberry's early life, the birth of "Star Trek," and everything that happened afterward will be told on the big screen.

Roddenberry's life should lend itself well to dramatization, though one would hope the film's producers will avoid the pitfalls of hagiography and depict Roddenberry from all angles, both flattering and otherwise. He was a brilliant and fascinating human being, albeit a flawed one, and his relationship to his most enduring creation had higher peaks and lower valleys than most people might expect. In fact, there are many things about Gene Roddenberry that "Star Trek" fans may not know, all of which could potentially show up in (or be suspiciously excluded from) the biopic. So if you're not sure what to expect from a Roddenberry movie, fire up the warp nacelles and let's explore together.

He was a pilot and a police officer

Gene Roddenberry grew up an avid science fiction fan, but his early life wasn't necessarily dominated by dreams of becoming a writer. His professional passions were police work (following in the footsteps of his father) and flying — he studied both police science and aeronautical engineering at Los Angeles City College, obtaining his pilot's license at the age of 19 via the Civilian Pilot Training program. The program had been set up in 1939 by General Henry Arnold, who was anticipating a war and a need for pilots — and after Pearl Harbor, Roddenberry flew 89 missions in the Pacific Theater of World War II, where he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal. Upon returning home, he became a civilian pilot for Pan American World Airways, which is where he was working when he first discovered television and decided to become a writer for the new medium.

Breaking into the writing business was far more difficult than Roddenberry had suspected, however. Having quit the airline and needing a way to feed his family, he returned to his roots and joined the LAPD, where he would cut his teeth writing speeches for Los Angeles police chief William H. Parker. He also supposedly used his role as a police officer to bully his first agent into representing him — a story that is almost certainly not true — but Roddenberry was becoming a writer, after all, and he told a mean tall tale.

He met many Star Trek contributors via a different show

Despite his police work, Roddenberry continued diligently in his efforts to break into television — which, by 1953, had finally become a stable enough industry to support ambitious newcomers. In fact, it was his police work that got him his first big break, when Ziv Television Productions began working on a TV version of the radio program "Mr. District Attorney," contacting the LAPD during a search for a technical advisor from the force. Roddenberry took the job, quickly became a writer on the show, and from there would go on to produce scripts for other programs as well, most notably "Highway Patrol," "The West Point Story," and "Have Gun — Will Travel." By 1956, he had officially quit the LAPD to focus on writing, and in the 1960s, he created his first greenlit TV show: "The Lieutenant."

An NBC drama about the lives of Marines during peacetime, "The Lieutenant" would introduce Roddenberry to many of the names that, like his own, would eventually become synonymous with "Star Trek." Legendary writer Gene Coon worked on "The Lieutenant," as did Joe D'Agosta, who was given his first casting director job by Roddenberry. The star of the show was Gary Lockwood, who appeared in the second "Trek" pilot, "Where No Man Has Gone Before." Most important, perhaps, was a parade of various "Lieutenant" guest stars who would go on to play major roles in the life and work of Roddenberry, including Leonard Nimoy and Majel Barrett (who would become Roddenberry's second wife), as well as the episode "To Set It Right," which featured the television debut of Nichelle Nichols.

He was friends with Isaac Asimov

In September 1966, mere weeks before the television debut of "Trek," Roddenberry flew to Cleveland to attend the World Science Fiction Convention. Nervous about how the show would be received, particularly by science fiction fans, he offered convention managers the chance for an exclusive screening of his new pilot, which they eagerly accepted.

As "Where No Man Has Gone Before" began to play, Roddenberry noted an audience member speaking loudly with friends and paying no attention to the show. Roddenberry confronted the malcontent, who sheepishly quieted down — as he returned to his seat, Roddenberry was informed that the man he'd just chastised was one of his personal heroes, science fiction legend Isaac Asimov.

The reaction to the screening in Cleveland was so intensely positive that Roddenberry ended up showing the original pilot, "The Cage," as a bonus. Afterward, Asimov approached Roddenberry to apologize and offer unmitigated praise for "Star Trek." As it turned out, this wouldn't be the first time the dynamic played out: later that year, Asimov wrote an article for TV Guide making fun of sci-fi shows for their lack of scientific accuracy, prompting a letter from Roddenberry defending himself.

As it happened, Asimov's apology letter was already in the mail — he had rethought his position and wanted to assure Roddenberry of his appreciation for and commitment to "Star Trek." This exchange marked the beginning of a deep friendship between the two, and Asimov even served as an advisor for what quickly became his favorite show.

He often rewrote Star Trek scripts

Roddenberry was the primary creative figure behind "Star Trek," but he was rarely credited as a writer on the show. Officially, he wrote 10 episodes, and for half of those he just wrote the story, not the teleplay. Unofficially, however, there were few episodes of the original "Star Trek" that weren't shaped in some way by Roddenberry's hand.

Not only was he always around to keep track of the details of the "Trek" universe and make sure everything in the show felt consistent and realistic, he often re-wrote scripts entirely. Part of the reason for this was his personal expertise in the universe he created, along with his obsession in maintaining control over that universe. Another part was that many of the "Trek" writers were published science fiction authors, and published science fiction authors don't always understand how to write for television.

The most notorious instance of this may have resulted in the best and most famous episode of the original "Trek": "The City on the Edge of Forever." Originally penned by sci-fi writer Harlan Ellison, the script was excellent — Ellison even won an award for it — but it would have been impossible to shoot on a television budget. So, Roddenberry ended up re-writing the entire thing, and the famously irascible Ellison never forgave him, becoming a "Trek" detractor from that day forward. For Roddenberry, it was just one of many scripts he doctored — and one of many bridges he burned.

He was famously difficult to work with

In actuality, there remains debate about whether "The City on the Edge of Forever" was re-written by Roddenberry or by Gene Coon, the other major creative influence on early "Trek" who is often credited with the best parts of the show. What's not debatable, however, is Roddenberry's tendency to feud with anyone and everyone around him. Whether it was his merciless (and, some say, inferior) script re-writes, his constant battles with NBC, or his insistence on absolute creative control, Roddenberry's intractable nature was well-known. Perhaps writer David Gerrold, who worked on both the original series and "Star Trek: The Next Generation," summed it up best: "Gene's pattern is that he doesn't work well with anyone."

This would bear itself out in the last season of the original series, unanimously considered its worst. After a legendary fan support campaign got "Trek" renewed for a third season, NBC hedged their bet by giving the show a terrible Friday night time slot. Roddenberry issued an ultimatum: the network would restore the original time slot of "Trek," or he would walk. NBC attempted to call his bluff, letting Roddenberry leave, although he remained on as executive producer.

He was also notoriously hostile during the troubled production of "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" and "Next Generation," engaging (alongside his lawyer) in verbal abuse and petty acts of intimidation that drove away cast and crew members alike. Some of Roddenberry's behavior can be explained by his failing health, but he was never easy to work with.

He had little success outside Star Trek

Whether you attribute it to his writing or his personality, Roddenberry had very little success in television (or any other medium) outside of "Star Trek." After leaving the series, he pursued a career in film, attempting to make a movie adaptation of the Asimov story "I, Robot" and a new version of "Tarzan." Neither would be produced — Roddenberry quit the "Tarzan" project upon securing a budget too small for his liking.

He did get one project off the ground, however, writing and producing the 1971 sexploitation film "Pretty Maids All in a Row." Widely reviled, the film did little to enhance either Roddenberry's earnings or his reputation. It's easy to forget that the original "Trek" was also considered a failure in its day, constantly in danger of going over budget and never a ratings success. Only the passion of the fans kept it alive — and for a time, their passion kept Roddenberry alive too, as he began to get his income primarily from appearances at science fiction conventions, especially those dedicated to "Star Trek."

It was the "Star Trek" convention phenomenon that eventually led Paramount (which by now owned full rights to "Trek") to bring Roddenberry back as executive consultant for both an animated series and a feature film. While the rapidly-deteriorating Roddenberry was largely ignored in this role, it was still more than he got out of his other attempts at sci-fi television, which universally ended in failure.

He had issues with women

One oft-cited reason for Roddenberry's lack of post-"Trek" success (as well as his frequent dismissal in later "Star Trek" productions) was his attitude toward sex and women. The original series is notorious for its female costuming — women on the Enterprise generally wore extremely short mini-skirts — and Roddenberry demonstrated similar tendencies throughout his career.

According to co-producer Morris Chapnick, Roddenberry's Tarzan script involved natives sacrificing beautiful, scantily-clad women. "I'm sure this had to be Gene's thing — they would all be in individual cages," Chapnick said. "Gene's fantasy, I guess."

It was understood that nude scenes were required for the female actors in "Pretty Maids All in a Row," who would also do a spread in "Playboy" for publicity. A commissioned 1974 Roddenberry script called "The Nine" turned autobiographical, and according to writer Harold Livingston, "He was also writing his various sexual perversions." His return to "Star Trek" was marred by his 1977 draft for the first movie, which contained, among other questionable choices, the line "Have you ever sexed with a human?"

These issues weren't limited to the page. According to Gene Coon assistant Ande Richardson, "Gene Roddenberry was a sexist, manipulative person who disregarded women." She's also spoken of his tendency to inappropriately share dirty or kinky sexual stories. Then, of course, there's his serial infidelity: Roddenberry's relationship with Majel Barrett developed for years while he was still married to his first wife, and he also had an affair with Nichelle Nichols.

He had a troubled relationship with Leonard Nimoy

It wasn't only screenwriters, network executives, and romantic partners who had issues with Gene Roddenberry. Leonard Nimoy played the role of Spock, one of the most popular and enduring characters in "Star Trek" history. Prior to his death in 2015, Nimoy went on the record on several occasions about his relationship with Roddenberry, saying that while he considered Roddenberry something of a father figure within the "Star Trek" family, he often wished they had been closer than they were.

At first, it was simply a matter of their senses of humor not matching up; in his 1995 book "I Am Spock," Nimoy discusses Roddenberry's fondness for pranks and making other people uncomfortable — but as time went on, the issues between them became more serious.

As an early story goes, despite not being the lead character, Spock was quickly becoming the most popular. Nimoy began wanting some sort of recognition for his efforts, financial or otherwise – a desire that Roddenberry and NBC tended to interpret as the actor's head swelling. So, during the much-maligned third season, Nimoy's fierce creative protectiveness over his character clashed with Roddenberry's increasing distance from "Trek," along with his financial ambitions.

Roddenberry re-wrote a Season 3 script to include a scene where Spock wears a strange medallion called an IDIC. The reason, it turned out, was that Roddenberry's mail-order merchandise business Lincoln Enterprises had begun selling that same medallion. In the unfortunate but true story, Nimoy — a "Star Trek" legend — would ultimately have a bad taste left in his mouth, feeling like his character had been betrayed by its cashing-in creator.

He wrote an early Star Trek novel

Roddenberry would end up having little influence on further "Star Trek" stories as the franchise moved forward via new television shows and feature films. He did, however, help kick off a considerably more prolific industry: The "Star Trek" novel.

Although it was predated by the works of authors James Blish and Alan Dean Foster, who novelized the original series and its animated successor, Gene Roddenberry wrote one of the first "Star Trek" novels — which was, ironically, an adaptation of "Star Trek: The Motion Picture." Perhaps due to the fact that Roddenberry had pitched multiple rejected versions of the script for the first "Trek" movie (which was eventually written by Alan Dean Foster), there have been rumors since the book's release in 1979 that it was written by Foster or some other ghost writer. However, Pocket Books editor David Hartwell confirmed Roddenberry's authorship to writer Jeff Ayers in his 2006 book "Voyages of Imagination."

As a result, Roddenberry became one of the pioneers of a series of novels that would eventually number in the hundreds, and which are still being produced today. As a fitting tribute to this legacy, Roddenberry was immortalized in one particular novel, "End Game," part of the "New Frontier" series by Peter David. In the book, the planet of Thallon is revealed to actually be a massive egg, and is destroyed when the egg hatches, revealing an equally massive bird: The legendary Great Bird of the Galaxy.

He never made it to space, but his ashes and his message did

Gene Roddenberry died in 1991, a few years after the premiere of "Star Trek: The Next Generation." Shortly afterward, according to NASA, his ashes were taken into a space shuttle by an unnamed astronaut, where they subsequently made it into orbit around the Earth (they were returned to Roddenberry's home planet after the voyage). His widow, Majel Barrett, said that Roddenberry "would have given anything to have been able, just once, to go into that great galaxy he dreamed about, where so few men have gone before."

For Roddenberry's 100th birthday, NASA went one step further, collaborating with the Roddenberry Foundation to host a panel discussion about Roddenberry's views on diversity, equality, and inclusion. NASA also used the Deep Space Network to transmit into space a 1976 recording of Roddenberry speaking on these issues. The message is aimed at the 40 Eridani star system, which is, according to Roddenberry, the home of the planet Vulcan.

In "Star Trek" lore, the Vulcans were the first alien species to initiate contact with Earth, making it a singularly-appropriate destination.

Interestingly, in 2018, a planet was, in fact, discovered to be orbiting the primary star in that system — a planet that could, theoretically, contain life. Of course, if another species does learn of us thanks to the broadcasted message of Gene Roddenberry, it'll be a little while before we know about it; Roddenberry's message won't reach 40 Eridani until roughly the year 2037.