The Ending Of Eraserhead Explained

Maybe you've heard the trending TikTok audio where the ever-eccentric director David Lynch tells an interviewer that "Eraserhead" is his most spiritual film — and when asked to elaborate on why, simply retorts "No, I won't." On social media, this clip is generally used by people offering up hot takes, but it's worth remembering that the actual exchange between director David Lynch and a BAFTA interviewer wasn't a bit. Lynch genuinely will not elaborate on the meaning behind one of his most popular works, "Eraserhead," and he's fine with viewers drawing their own conclusions.

The 1977 surrealist indie film is the type of movie you can't explain to someone who hasn't already watched it. However, even if you've watched it a million times, "Eraserhead" is intangible — and not in a pretentious, film snob way. The monochromatic black and white body horror is notoriously difficult to understand and Lynch has remained adamant that it stays open for interpretation.

So, what might that abstract, uncanny ending mean?

As Eraserhead shows, parenthood can be anxiety-inducing

The most simple explanation for the unexplainable ending of "Eraserhead" is that it's the culmination of a new father breaking under the pressure of raising a baby he didn't want. Sure, the baby is a grotesque, howling, alien-like creature, but it's still his child and he bears some responsibility to it.

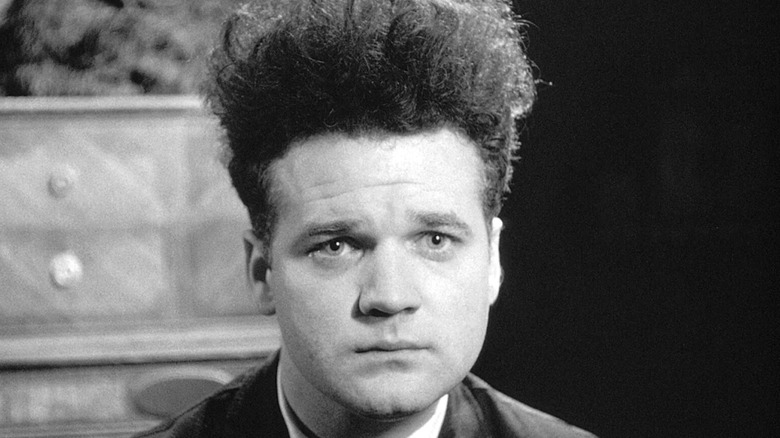

The film follows passive, blank-slate father Henry Spencer (Jack Nance) and his statuesque hairdo as he becomes increasingly unnerved by the clothbound lifeform lying on his desk day after day. The baby's incessant crying drove Spencer's wife, Mary X (Charlotte Stewart), to run out in the middle of the night. Alone, he must reckon with the emotional turmoil of the increasingly sickly baby until he finally snaps.

In the nightmarish finale, Spencer begins to snip the baby's bandages. The baby panics and it's revealed that its organs were held together only by the tightly bound cloth. With a screaming baby and its fully visible organs, Spencer realizes he only has one option left that could spare both of them. He punctures the baby's lung, resulting in an ooze of fluids that painstakingly morphs into an all-consuming foam. Outlets begin to spark and industrial noise adds to the horrifying atmosphere as Spencer watches the creature choke out its final breath.

Fans have speculated that David Lynch was inspired by his unplanned daughter, Jennifer, who was born with clubfoot. However, he counters that everyone draws inspiration from what is going on around them. "Obviously, since a person is alive and they're noticing things around them, ideas are going to come. But that would mean there'd be a hundred million Eraserhead stories out there. Everybody has a kid and they make 'Eraserhead'? It's ridiculous! It's not just that. It's a million other things" (via Criterion).

Eraserhead really is Lynch's 'most spiritual film'

In that same BAFTA interview, Lynch followed up his iconic "No, I won't" line by saying, "No one sees it that way, or maybe somebody out there does, but it is." He just really doesn't want to tell us why. No, seriously.

In his 2006 autobiography "Catching the Big Fish," Lynch explained that he was trying to make sense of the film on a grand scale and found himself reading the Bible. "And one day, I read a sentence," he wrote. "And I closed the Bible because that was it; that was it."

The Bible verse in question? Nobody knows for sure. Some Lynch fans have taken to Reddit to speculate, like user NotAGhostProbably, who offered two possible contenders based on hints in the film. No matter how correct this seems, though, they ended their analysis by saying, "Obviously this can't be confirmed without Lynch, and I doubt he'd confirm it even if it was right."

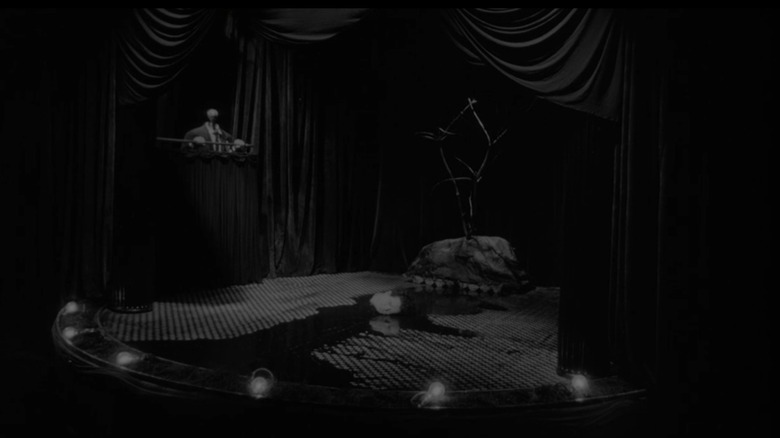

What he has confirmed is that the Lady in the Radiator (Laurel Near) symbolizes hope for Spencer. A manifestation of his anxiety, her presence offers a second chance or a way out. Fans often interpret her as encouraging Spencer's suicidal ideation, but if Lynch is to be believed, she may be Spencer's spiritual conscience. After he kills the baby, he is embraced by the Lady in the Radiator and appears to be at peace with his decision.

More than a few Freudian slips

The film's prologue and epilogue consist of abstract, galactic conception and death sequences. "Eraserhead" is brimming with lust and sexual undertones, from the rolling eyes and gyrating chicken dinner to the fleshy being's pulsating organs, as well as the suggestively spurting liquids and sperm-shaped motifs throughout.

Spencer's killing of the baby is prompted by the rejection from the Beautiful Girl Across the Hall (Judith Anna Roberts). The baby laughs at him, in its wheezing sort of way, just before he picks up the scissors. Reeling from the rejection and feeling remorse for their one-time affair, he snaps. The emotional confusion of being left by his wife over their baby coupled with the lust for his seductive neighbor leads to the vaguely reverse-Oedipal killing (via Criterion).

The repeating motifs and sexual themes are bookended by the dreamlike space sequences and then by Spencer's visions throughout. It's difficult to say why his reaction to seeing the neighbor with another man brings about his rage toward the baby, but Freud would have a field day with that one.

Eraserhead may never have a clear explanation

Fans can theorize all they want over what "Eraserhead" is about and what the ending means, which is precisely what David Lynch wants. Much of his work, from "Mulholland Drive" to "Lost Highway," remains without any solidly defined, self-imposed explanation — the work is meant to speak for itself.

In that same 2014 Criterion interview, he said, "I love the idea that one thing can be different for different people... Even with a standard, spoon-fed film, people see it differently." He's maintained that stance since 1979, when he told an interviewer, "...it's not fair for me to say, 'Oh, you didn't get it,' you know, because the film is so abstract."

Lynch's refusal to pin down the film's meaning shows his commitment to the vision and his belief in his art being viewed as "anything goes." As a result, the director's style has led to the descriptor "Lynchian" being attached to any surreal, confusing film experience.