The Ending Of Perfect Blue Explained

Satoshi Kon stands tall in the pantheon of great filmmakers who left us too soon. Arguably the most original and visionary new voice to break out into the world of animation in the past 30 years, the Japanese director only made four feature films, each one more stunning and mind-blowing than the last, before his passing in 2010. By then, it was clear from his most recent work that Kon would go down as a legend, and, sure enough, his 2000s output continues to be immensely influential in both the East and the West to this day. But greatness was already in the cards for Kon as early as 1997, when he made his first feature, "Perfect Blue."

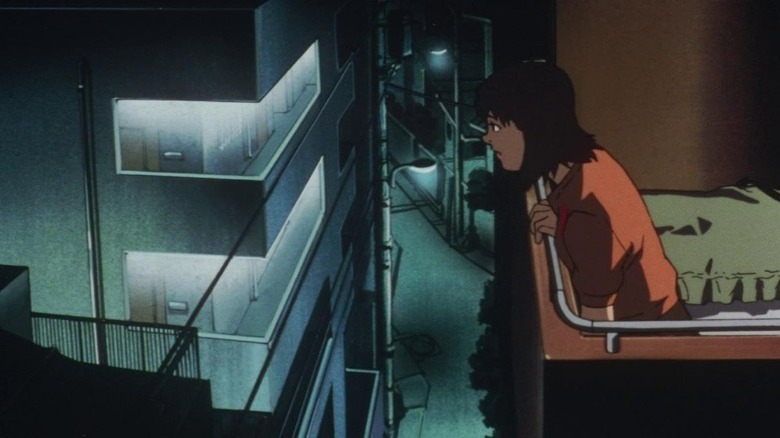

A surreal psychological horror with no pretense towards spectacle or adventure, "Perfect Blue" is all paranoia, all the time: We begin by following former J-idol Mima Kirigoe as she gets acclimated to the set of a drab TV procedural, then worry alongside her as stalkers and possessive fans encroach on her personal life. Finally, we go off the cinematic deep end when Mima is overtaken by psychosis. Unlike Kon's other films, in which there's an element of grandeur and exuberance to the surreal escalation, Mima's breakdown is ugly, rough-hewn, and relentlessly disturbing. Kon uses confusion as a tool, ultimately displacing the bounds of narrative to such a degree that it's impossible to keep enough distance from Mima to be "entertained" by her fate. It's a radical exercise in empathy, and the result is one of the most terrifying anime you can watch. Here's why the film — and especially its ending — is so effective.

Perfect Blue's climax ramps up the intensity in an unusual way

The first rule of filmmaking is that there are two basic components in every movie: the things that happen within a shot, and the relationships between one shot and the next. By its very nature, animated cinema tends to pay closer attention to the former component, as the whole appeal of animation as a medium is that it allows for boundless visuals and movement. Surrealist animation, in particular, usually favors fluid, psychedelic motion, of the sort that couldn't possibly work in live-action — that's very much true of Satoshi Kon's 2006 film "Paprika."

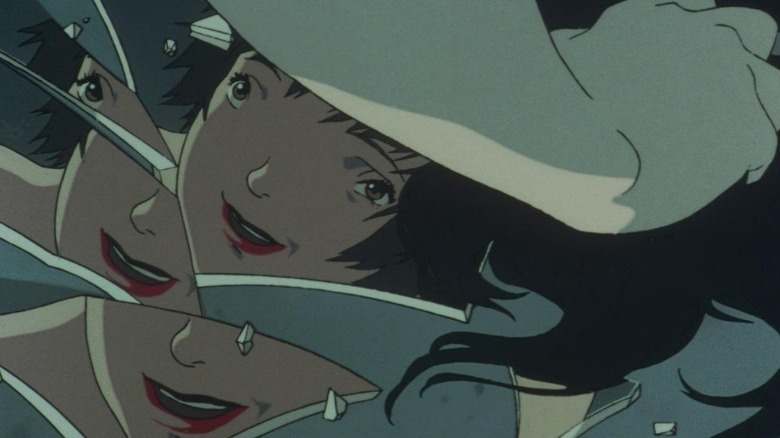

The ending of "Perfect Blue," however, doesn't conform to that expectation. It could almost be the ending of a live-action movie. Instead of grand, trippy visuals, Kon pulls us into Mima's head by way of editing. The deeper Mima falls into psychosis, the more the shot relationships stray from a linear structure, breaking with logic, zigzagging from future to past and from reality to fiction, and insisting on vicious repetitions until we're left utterly and hopelessly disoriented as to what's real.

That's because the climax isn't meant to be impressive: It's meant to be deeply felt. A less empathetic film would have made a meal of the final Mima vs. Rumi showdown and its myriad avenues for kaleidoscopic beauty, but "Perfect Blue" sees it for the tragic moment it is. Mima is, above all, baffled at the revelation that her manager is a deranged murderer, so we must feel the same way. The confusion and numbness we experience are integral to the horror — as well as to the underlying themes.

The tragedy of Perfect Blue is multi-layered

As Mima loses her grip on reality, she also loses her sense of who she is. She's no longer able to tell whether or not she's the "real Mima," whether things on the "Double Bind" set are happening to her or to her character, or even how it was that she last decorated her own apartment. But, as these uncertainties pile up, we, the audience, only grow to understand Mima better. Kon does away with all the external definitions the world imposes on her — her aesthetic presentation, her career, her public image — and ropes us right into her experience. This is one of being a female pop star whose identity and agency are subjected to an endless tug-of-war involving the media, her fans, and her management. The horror of "Perfect Blue" is that Mima isn't allowed to know who she is or what's going on, and so the movie doesn't allow us to know, either.

At the same time, "Perfect Blue" has equal empathy for Rumi, the manager who developed a parallel personality as "the real Mima" and began to kill anyone who steered her client's career in a more adult direction. As a former pop idol herself, Rumi has been through the same wringer as Mima; her condition is the long-term result of a life of dehumanization. She clings to the candy-colored gloss of CHAM! because maturity only brings women like her and Mima further suffering, as demonstrated by Mima's own experience on "Double Bind." Ultimately, patriarchal society offers them no escape.

The final line is chilling however you interpret it

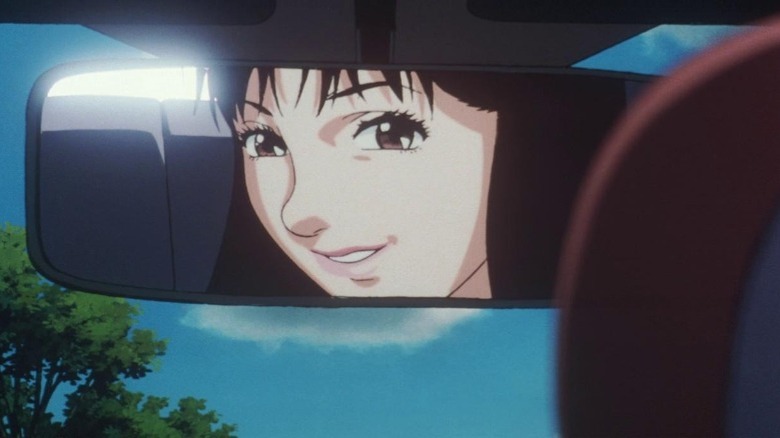

This multi-layered tragedy, with Rumi as simultaneously a ghost of Mima's past and a terrifying mirror image of her possible future, is resolved as abruptly as it's revealed. Following the climatic violence, we go to an epilogue in which it's revealed that Mima is now a renowned dramatic actress, and Rumi is in a psychiatric hospital. The sense of unease never really wanes, though — everything happens so fast that we still haven't had time to settle into "normality" by this point. To assuage our concerns, the final scene sees Mima suddenly look at us through the rearview mirror of her car, and then say, in the most saccharine voice, "I'm the real one!"

Here's where it gets complicated: In the American dub, the line — a slightly tweaked "No, I'm the real thing!" — is delivered by Mima's voice actress Ruby Marlowe. That ending can be reasonably read as an inconsequential meta-joke. In the original Japanese version, though, the final line is said by Rica Matsumoto, who voices Rumi (via TV Tropes). So is the entire epilogue intended to be another of Rumi's hallucinations?

We probably can't be certain, but any interpretations should take into account that Matsumoto also provides Mima's singing voice at the beginning of the movie. Therefore, the last line either reveals we're actually looking at Rumi, or it draws a chilling thematic parallel between Mima's newfound prestige as an actress and her J-pop past, implying they're sides of the same coin. Neither ending offers Mima the comfort she — and we — crave. After all, hers isn't merely a situational problem, but a societal one.