The Ending Of Knowing Explained

The late Roger Ebert was, for a long time, America's foremost reference point when it came to movie reviews and commentary, frequently shaping the public's perception of whether a movie was "officially" good or not. And, though he was sometimes admonished for being too harsh on beloved movies, it was just as usual for Ebert to throw enthusiasm behind the most unexpected of new releases — such as when he gave a perfect score to "Knowing" (via RogerEbert.com).

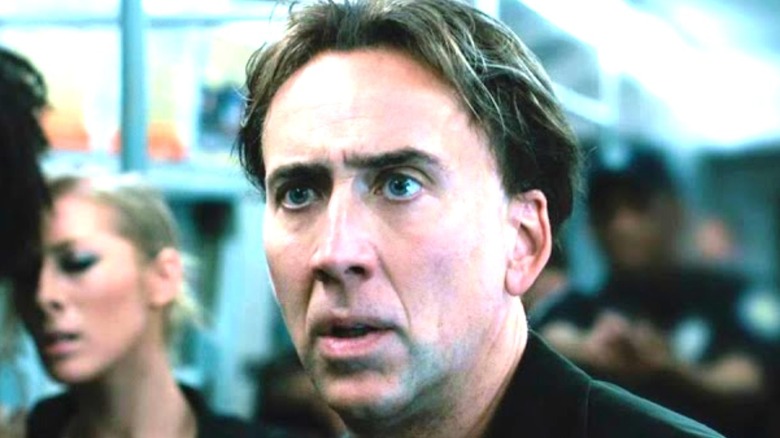

In retrospect, Ebert's sanguine support of the Nicolas Cage sci-fi thriller, which also included ranking it "among the best science-fiction films I've seen" and including it in his 2009 year-end top ten list, is a lot less baffling than it seemed at the time, when "Knowing" was getting widely panned by critics. As much as the portentous tone adopted by director Alex Proyas ("Dark City") may invite cynicism, "Knowing" really is, at the end of the day, a highly effective slice of conspiracy paranoia; the story of John Koestler (Cage) and Diana Wayland (Rose Byrne)'s quest to untangle the truth of the Lucinda Embry numbers fully capitalizes on the inherent power of keeping the audience in the dark.

Plus, unlike many movies like it, "Knowing" builds to a conclusion that's actually up to the breathless standard of the buildup. It's an ending so over-the-top that it almost certainly kept the movie from being taken seriously by certain critics and casual viewers. But for those on the right wavelength, as Ebert was, the finale of "Knowing" is a barn-burner.

What happens at the end of Knowing is simple — the question is what it all means

The main emotional fuel for most of "Knowing" is paranoia: John and Diana know that something terrible is afoot, and the tension stems from their simultaneously desperate and reluctant pursuit of more information. The only honest way to end the movie would be to deliver something on the scale of their deepest-seated fears, and that's just what "Knowing" offers. The beings who have been whispering into Caleb's (Chandler Canterbury) and Abby's (Lara Robinson) ears finally reveal themselves as a more evolved alien race, who have been landing space arks all over Earth to save a select few humans and animals from the imminent destruction of the planet. They save Caleb and Abby, leaving John to die along with most of mankind in the solar flare event, and the children are taken to safety on a heavenly new planet.

All of this is quite simple and straightforward. So why is the ending such a headscratcher? Well, as it happens, "Knowing" operates by a metaphorical framework so overt that it's impossible to just take it at face value. There's obviously a deeper meaning to it all. Inevitably, there are innumerable different ways to interpret the aliens, their means of communication, the solar flare, and the new planet, such that no one explanation can be "correct." But there is, at least, one reasonably safe place to start: the Bible.

Is Knowing a Christian film or a radically secular one?

The parallels between "Knowing" and the Old Testament's Book of Ezekiel are rather blatant (via Bible Hub): The book's first chapter speaks of "living creatures" with "the likeness of a man" that come to the prophet enclosed in "a wheel in the middle of a wheel" (via Bible Hub) — exactly the shape of the aliens' space arks in "Knowing." This, coupled with the movie's earlier incorporation of Ezekiel's chariot vision in an engraving, raises the possibility that the whole thing is inspired by the Book of Ezekiel, and that the aliens are not aliens, but angels.

Then, there are also references to other Biblical passages, which suggest a more pick-'n'-mix approach to Christian mythology: John's separation from his son Caleb calls to mind the Matthew verse "Then shall two be in the field; the one shall be taken, and the other left," and the bringing of the kids to the new, Eden-like planet could be interpreted as a Rapture, following the Revelation-like reception of the beings' whispers. All in all, "Knowing'"s ending can be taken to visualize the overarching Christian belief in the saving of an elected few by a higher power.

It can also be taken, however, to mean something else entirely. If we abstract "Knowing" away from the realm of metaphor and view the story through a more literal lens, it reveals surprising similarities with the works of Erich von Däniken, the 20th-century Swiss writer famous for theorizing that ancient human religions were a result of contact with aliens. This ambiguity between Christian metaphor and radically secular speculation explains the movie's divisive reputation among Christians, detailed on the website ChristianAnswers.net.

Knowing is as much a spiritual film as a film about spirituality

Whether you read "Knowing" as a movie about angels mistaken for aliens or aliens mistaken for angels, one thing is for sure: The movie gets, and incorporates, much of the existential appeal of spiritual devotion, as well as many of its tough underlying questions.

Roger Ebert himself argued as much in a passionate defense of the movie, which he wrote in response to the negative reviews: "The ending is spectacular enough that it brings closure, if not explanation," the critic wrote on RogerEbert.com. "I don't have to know if the beings are aliens or angels. Nobody in the movie does." Ebert understood that, as concerned as "Knowing" is with certain Christian symbols, it's every bit as concerned with the emotional reality of living among — and responding to — those symbols. John Koestler is a skeptic going through a religious awakening: He rummages the Lucinda Embry numbers as a believer does a sacred text, equally convinced that they speak to a larger truth, and he doesn't have to understand all of it to believe. It's no wonder the movie ends with him reconciling with his pastor father (Alan Hopgood).

It's also no wonder that, earlier on, he engages in what Ebert calls "a cerebral debate at MIT about whether the universe is deterministic or random." For both John and Diana, the conspiracy is at once soothing and frightening. It may help them process their grief and anxieties better — but it may also seal their fate and tell them the day they will die. The comfort of faith comes at the cost of submission to a sometimes unknowable wisdom. Is it worth it? That, of course, will depend on the viewer.