Everything The Imitation Game Doesn't Tell You About The True Story

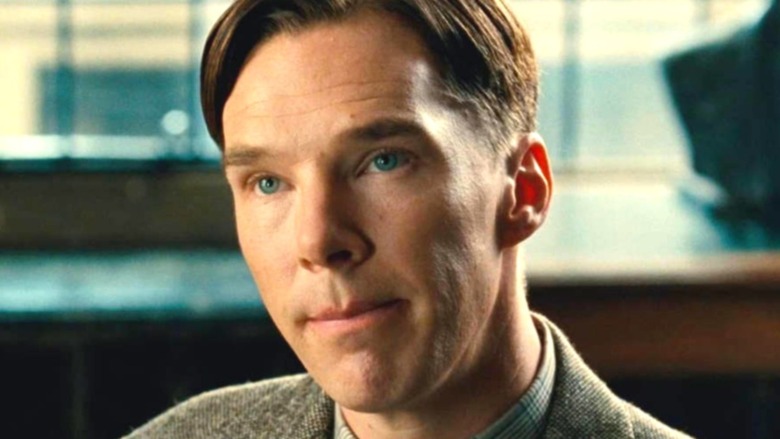

When you think of the best war movies ever made, you probably think about intense battles, heroism under fire, and lots of explosions. But the truth of World War II was that much of the war went on at desks all around the world. "The Imitation Game" tells one such story, specifically the one about cryptology, computing, and mathematical prodigy (whether he would use that word or not) Alan Turing, played by Benedict Cumberbatch.

"The Imitation Game" tells us the following narrative: Turing was hired to break German ciphers at Bletchley Park, the secretive center of Britain's codebreaking operation. The most difficult of all was the well-named Enigma, generated by a machine that used a system of rotors and a plugboard to create an almost impossible-to-crack cipher. At the same time, Turing's meticulous and obsessive personality grated on his coworkers, he was constantly scrutinized by Bletchley Park leader Commander Denniston (Charles Dance), and he lived in fear of people finding out he was gay. (The U.K. didn't start to decriminalize homosexuality until 1967, 13 years after Turing died by suicide, and it wasn't until 2003 that the law used to convict Turing was repealed in England and Wales.)

However, we're sorry to report that "The Imitation Game" is actually one of those biopics that lied to your face. The interpersonal drama at Bletchley Park was played up, and the movie actually played down just how impressive the effort to break Enigma really was. This is what "The Imitation Game" left out about the true story of Alan Turing and Bletchley Park.

Alan Turing got on well with his Bletchley Park colleagues

In "The Imitation Game," Alan Turing struggles socially with his peers. He's show as having a tendency to take things literally, and frequently misunderstanding jokes and figures of speech. However, people who knew Turing in real life recalled that he was easy to work with and friendly. As The New Yorker's Jim Holt notes, Turing "impressed his colleagues as a friendly, approachable genius, always willing to explain his ideas." Olive Bailey, a fellow codebreaker at Bletchley Park, told CBC News that Turing "was inclined to talk in bursts ... but he had a lovely sense of humor, and we got along very well."

This experience was also reflected in Turing's relationship with the daughters of his psychologist Franz Greenbaum, whom Turing started seeing for therapy in 1952, after being convicted of homosexuality. The youngest daughter, Maria, described him to the BBC as "a very warm and friendly person who always took an interest in what I was doing." If Turing could find the patience to write to a child about solitaire, he could probably cope with working alongside some of the most talented mathematicians in the world on a top secret government project.

That said, Turing did have some charming eccentricities. He did like to run and cycle, as shown briefly in the movie. Turing also often wore a gas mask while cycling, as it helped keep pollen off him and keep his recurring bout of hay fever from returning.

Commander Denniston supported the codebreakers

Although the depiction of Alan Turing's interactions with his colleagues in "The Imitation Game" was inaccurate, the character that the movie arguably gets most wrong is Commander Denniston, played by Charles Dance. In the film, Denniston is the crotchety Naval man who doesn't have time for all this mathematical nonsense. In reality, Denniston himself had worked as a cryptologist during World War I, which is why he was a good candidate to head up codebreaking operations at Bletchley Park. After the release of "The Imitation Game," Denniston's relatives wrote a letter to the Daily Telegraph, saying that he was "completely misrepresented" and accusing the movie of throwing him into the role of the bad guy. According to Libby Buchanan, Denniston's niece, he was a "quiet, dignified" man entirely unlike what "The Imitation Game" portrays him as.

Another real-life figure who makes an appearance in "The Imitation Game" actually was considered a villain in real life, but not for the thing the movie accuses him of doing. John Cairncross (Allen Leech) worked as a translator at Bletchley Park, and later for MI6. In 1991, it was confirmed that he'd spied for the Soviets in World War II and beyond, as part of the infamous Cambridge Five spy ring. In the movie, Turing realizes that Cairncross is a spy, but Cairncross blackmails him into staying quiet by threatening to reveal that Turing is gay. In real life, the level of security at Bletchley meant that the two men — who worked in totally different departments — probably never even met. And Turing was quite open about being gay, at least among his friends and colleagues.

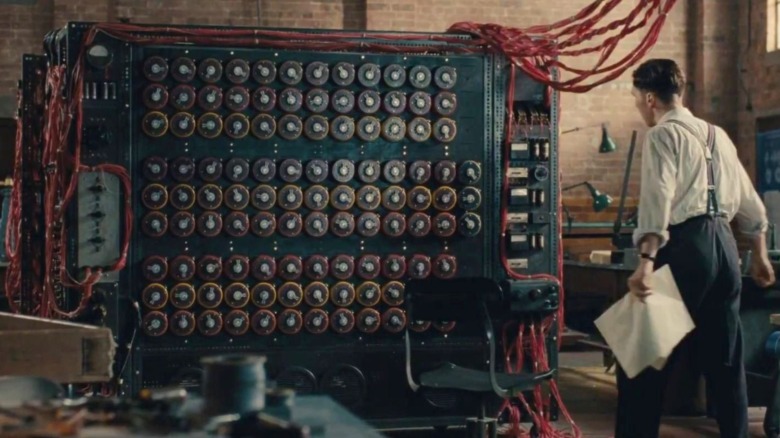

Alan Turing didn't single-handedly build the machine that cracked Enigma

Yes, Alan Turing helped win World War II. He was undoubtedly a genius whose contribution to victory over the Nazis went uncredited long after his death. And he really was arrested and convicted for being gay, and forced to undergo chemical castration. However, unlike in the movie, the police didn't learn that Turing was gay while investigating him for being a Soviet spy, and he was arrested in 1952, not 1951.

"The Imitation Game" also plays up Turing's role in cracking Enigma to make it look like he worked on it practically single-handedly. In reality, three Polish mathematicians — Marian Rejewski, Henryk Zygalski and Jerzy Różycki — had been slowly cracking Enigma throughout the 1930s. In 1939, as the German invasion of Poland became increasingly likely, the Polish government handed the three men's work over to allies in France and Britain. This included a machine designed to break the code, called a Bomba. Turing named his improved version of the machine Bombe in its honor. He worked alongside Bletchley colleague Gordon Welchman, whose contribution led to a reduction in false results. Welchman, Rejewski, Zygalski and Różycki aren't even mentioned in "The Imitation Game."

As you'll remember, in the movie, the machine is named Christopher after Turing's first love. Christopher was real, although Turing suspected he didn't return his affections. His death also wasn't as much of a surprise to Turing, who had been prepared for it before the holidays. However, losing Christopher did affect him greatly. Part of Turing's fascination with artificial intelligence stemmed from his hope that part of Christopher's consciousness could be recreated. "The Imitation Game" director Morten Tyldum explained that he changed the machine's name to reflect this belief, and that it was "the emotional truth."