Come True Review: Bad Endings Matter

Anthony Scott Burns wears many hats in his new sci-fi/horror flick Come True, a movie he wrote, directed, edited and shot himself. But for all the atmospheric dread and stylized suspense he musters through its runtime, the one role he can't ascribe to himself is "closer."

Because when it comes to the building blocks of what makes for a good movie, conceiving of a good ending possesses a weighted score within the larger pie chart. You, as a filmmaker, can get everything else right, but if you can't stick the landing and close your story on a strong note, the rest is all for naught.

Come True finds its origins in fertile ground for genre experimentation, dealing in the world of sleep and dreams. It stars Julia Sarah Stone as Sarah, a teenage runaway seeking refuge from camping out on playgrounds in a sleeping bag. When Sarah finds a sleep study that pays its subjects just to dream, she thinks she's found the answer to all of her problems.

But in short order, things get far worse than waking up next to a swing set.

Imitation and flattery

The main thrust of the story comes from the convergence of two distinct visual worlds: the blue-ish/gray hue of Sarah's real world inside the sleep facility (itself occasionally broken up by blinding, washed-out daylight shots of her time between sessions) and the haunting, Silent Hill-level visions of Sarah's unsettling dreams.

Unlike the majority of horror films that find scares in depicting nightmares that initially look like "real life" only to give way to typical jump scares that reveal them to be the ravages of the subconscious, Come True finds experienced visual effects artist Burns conceiving of Sarah's dreams, and truly those of her fellow subjects, as disturbing, carefully designed POV sequences set within a dark and murky procession of twisted storybook imagery.

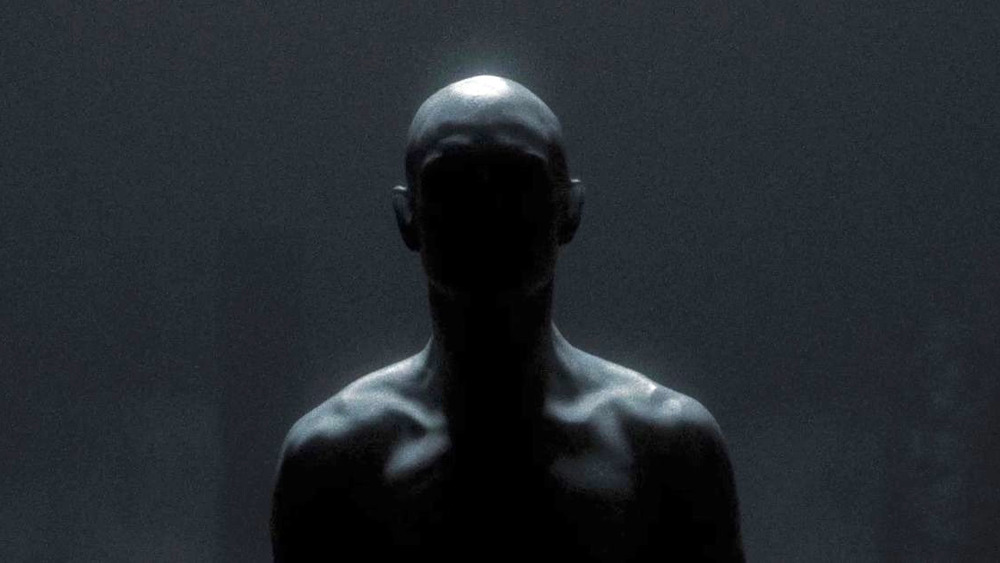

These dreams and their abstracted spaces provide a great atmosphere, but there's a singular figure, an imposing dark shape with glowing eyes, that proves the real focal point in the scary showcases. In time, it's revealed that this figure doesn't only exist in Sarah's dreams, but the dreams of literally everyone who sleeps, and that this phenomenon is the true motivation behind this ongoing study.

At first, the viewer might wonder what the underlying ideas Burns wants to explore from inside this framework might be. Sure, sullen girl sees spooky shadow at night — big scare. But horror and science fiction are two genres that require some sort of thematic substance lingering beneath their dramatic excursions. Is the spooky figure supposed to represent whatever repressed trauma that has sent Sarah scurrying from her own home?

Well, not really. Burns, for all the work his script attempts to do with the story's curious mythology, holds very little interest in exploring why Sarah is a runaway, or what drives her, or what holds her back. This is a movie less concerned with straightforward narrative, or even in depicting a significant feeling. It's a project more concerned with vibes.

Not unlike David Robert Mitchell's It Follows, this is a genre exercise more principally concerned with curating the right aesthetic, culled from a hodgepodge of '80s influences. Wes Craven is there in the nightmare realm, David Cronenberg right down the hall in the unsubtle cross section between science and scares. If you felt like there might be an early James Cameron vibe to the proceedings, the prominent Terminator poster in the background of an office tells you it wasn't just a hunch.

The carefully orchestrated cinematography and the throbbing synth score from Burns himself (as his alter ego Pilotpriest) and Drive soundtrack veterans Electric Youth further underscore the sort of film Come True is supposed to be. But while there's nothing wrong with a stylish, moody thriller conjoining a number of indelible inspirations into a new cohesive whole, Burns clearly budgeted more creative energy to the tone than the story itself.

A twist too far

Up until its closing act, Come True, probably by virtue of its entrancing aura and sturdy craft, seems like a movie that will overcome its ambitious, largely formless narrative to draw the curtains on an impactful finale. But instead, it indulges in two late creative decisions that undo any of the goodwill it may have earned previously.

First, it extrapolates a subplot from early in the film that might have, in nimbler hands, been subverted or dropped entirely. Degrassi alum Landon Liboiron features in the background as Jeremy, a scientist working on the sleep study who seems drawn to Sarah. We first meet him casually stalking her in public before discovering he knows her from the program. But from the jump, this clearly adult man following a vulnerable teenager around proves just as creepy as the sleep paralysis demon analogue who keeps appearing in her nightmares.

Rather than reveal malicious intent in his aims or explore the dichotomy between real-life boogeymen and the ones from dreamland, the film, for no discernible reason, follows this through-line to Sarah and Jeremy consummating their weird bond, with Burns trying in vain to hand wave away how gross this development feels by having Sarah awkwardly reveal that she is, in fact, 18 years old. Flashing that your film's waifish lead, heretofore presented solely as the literal manifestation of every mother's fear of her daughter appearing on the side of a milk carton, is in fact of legal age just in time to throw in a gratuitous sex scene feels more discomfiting than any of the film's delicately orchestrated attempts at cinematic horror.

But even that could, in theory, be forgiven, if the rest of the third act found a way to build upon the film's mythology to leave audiences with a positive lasting mark. For a few minutes, it even feels like Burns is going to pull it off, setting up a profoundly disturbing sleepwalking sequence involving Sarah that feels as if it's building to a truly stirring climax.

Instead of doing that, however, Come True transforms into a slow-motion train wreck, an absolute disaster of logic and good sense hurtling carelessly into one of the dumbest, most insulting twist endings in recent history. This isn't so much a film that trips on its own two feet while sprinting to the finish line as it is one that pole vaults over the collective heads of its audience to land on the other side in a shark tank, eaten alive for a questionable spectacle whose reasoning could take years of independent, peer-reviewed study to ever unpack.

This is a film that earns serious confidence from the viewer through its multi-hyphenate creator's strong visual work, only to be offensively undone by his lack of storytelling acumen and a final scene bad enough to warrant lifelong infamy. Come True is the rare film that would somehow be improved by ending with its main character waking up, looking at the camera, and muttering "It was all a dream."