Our Lord Of The Rings Expert Answers The World's Most Difficult LOTR Questions

Middle-earth is a vast place. One gets the feeling that even J.R.R. Tolkien himself never explored or even understood more than a fraction of his fantasy world. Even so, the author certainly managed to record an enormous number of details about the intricacies of Middle-earth — everything from big picture items like the creation of his world to minor trivia like why wizards inhabit old-man bodies. While this information is available, it often takes years of reading Tolkien's writings to even start to make head or tails out of the endless, labyrinthine minutiae.

As for fans of the movies, the complexities of Middle-earth are often straight-up mystifying. The dense yet rapid pacing of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit trilogies naturally leaves countless questions in their collective wake. Sometimes these come from creative liberties taken by writers and directors. At other times, they arise from a lack of exposition or an inability to properly slow down and explain a minor detail.

This adaptation-induced clutter can create a convoluted feeling that makes it difficult to fully enjoy the cinematic experience. With that in mind, we've gone ahead and gathered a collection of the most challenging movie-based questions and then tapped the source material to dig up the best answers. So, without further ado, here are the book-sourced explanations for some of the most difficult movie-related Middle-earth questions out there.

Why do elves and dwarves despise one another?

Right from the get-go, elves and dwarves clearly have a beef with each other. The two ancient Middle-earth races are at odds at practically every step. In The Hobbit, the dwarves roll their eyes at the elves of Rivendell, and they're literally imprisoned by and then fight with the Woodland Realm folk in Mirkwood. In The Lord of the Rings, Gimli and Legolas start off their famous friendship at odds, the elven princeling hates the idea of going into Moria, and the dwarf is nearly refused admission into Lothlorien.

What is it with all the "hostility at first sight" stuff? It's a theme that stretches far back, throughout their ancient history, which is depicted in The Silmarillion. This reveals that the root of the conflict goes all the way back to their creation.

See, dwarves were brought into being by an angelic creature named Aulë in an act of disobedience. He was impatient as he waited for the Creator, Ilúvatar, to bring the elves into the world that he and his fellow spirits had prepared for them. Ilúvatar caught Aulë, but he chose to give his creations their own individual wills. However, he also told Aulë that "often strife shall arise between thine and mine, the children of my adoption and the children of my choice." This immediately set the tone for the dwarves to live fiercely independent lives, separate from and often at odds with their elven brethren as the two races navigate the world side by side.

Where do orcs come from?

In The Two Towers, Treebeard tells Merry and Pippin that orcs were made in mockery of elves during the Great Darkness very early in Middle-earth history. However, Tolkien never definitely clarified the specific origin of the orcs. Nevertheless, in The Silmarillion, he does offer one very compelling account about how the hideous servants of evil likely came into being.

Tolkien explains that when the elves first came into existence, they were alone and lived in childlike innocence in a world of perpetual starlight. Eventually, they became scared to wander off individually or in small groups, as an unknown being that they called "the Hunter" often carried them off.

This Hunter turned out to be the Dark Lord Morgoth and his servants. The fate of his captives was uncertain, but it was surmised by the wise of Middle-earth that they "by slow arts of cruelty were corrupted and enslaved; and thus did [Morgoth] breed the hideous race of the orcs in envy and mockery of the elves, of whom they were afterwards the bitterest foes."

While the orcs likely started as corrupted elves, before long, they took on their own attributes. Particularly, they multiplied faster than elves. But even as the enemies of elves, dwarves, and men, Tolkien points out that deep in their dark hearts, the orcs still "loathed the Master whom they served in fear, the maker only of their misery." The creation of the orcs is referred to as "the vilest deed of [Morgoth], and the most hateful to Ilúvatar."

How are the Uruk-hai different from other orcs?

So, what's the deal with Uruk-hai? How are Saruman's oversized servants different from their orcish counterparts? After all, they appear to have orcish features, but they're uncommonly tall and muscular. Much like the history of the orcs themselves, Tolkien is never crystal clear about the answer. But he does give a couple of guesses in The Two Towers book.

First of all, it appears to be safe to refer to the Uruk-hai as an offshoot breed of orcs. In other words, they are, at least partially, part of the "orc family tree," so to speak. However, there are a couple of uncomfortable guesses made as to how Saruman may have beefed them up so much — and it doesn't have to do with incubating them in strange mud pits, as seen in the Peter Jackson adaptation.

In The Two Towers, Treebeard states that Saruman has been "doing something to [the orcs]; something dangerous. For these Isengarders are more like wicked men." He adds that normal orcs cannot stand the sun, but the Uruk-hai can, even if they don't love it. From there, the arboreal fellow conjectures, "Are they men he has ruined, or has he blended the races of orcs and men?" During the Battle of Helm's Deep, the Uruk-hai are also referred to as "half-orcs and goblin-men that the foul craft of Saruman has bred." While it remains hazy, it appears that the White Wizard may have crossbred orcs and men to create his corrupt soldiery.

What does the One Ring even do?

What does the One Ring actually do? This is kept vague in both the movies and the books. However, if we cobble together enough of the facts, we can get a better picture of why the shiny, overpowered trinket is so coveted by everyone who sets eyes on it.

First off, in The Silmarillion, it explains that Sauron forges the One Ring partway through the Second Age. When this happens, he binds the other Rings of Power to it in order to gain an intimate level of domination over their owners. In doing this, "much of the strength and will of Sauron passed into that One Ring." Sauron is able to use the Ring to see what the other Ring-bearers are thinking and even control their thoughts.

However, Sauron's initial plan backfires, and the elves prove strong enough to avoid his jewelry-driven domination. Nevertheless, the One Ring retains its control over most of the other Rings of Power and continues to exist primarily as an instrument of evil domination.

While this is the primary use of the One Ring, the bauble also provides several other advantages. Obviously, it can make an individual disappear when they want to. It can also stop the aging process indefinitely. On top of that, when Sam briefly puts on the Ring after Shelob's lair, he understands the conversation of nearby orcs. This is explained as either the Ring giving him "understanding of tongues" or possibly even a straight-up general understanding of the thoughts of Sauron's servants.

How long did Frodo have the One Ring before he left the Shire?

This question shouldn't even be an issue in the first place. However, the timelines of Jackson's movies and Tolkien's books are jumbled fairly early in the telling. This throws off the timing of the whole story, leading to the question, how long does Frodo have the One Ring before he becomes Mordor-bound?

The correct answer is 17 years. Yes, you read that right. Frodo receives his inheritance from Bilbo on his 33rd birthday. In the movie version of that long-expected party, we see Merry and Pippin practically full-grown as they get into trouble with Gandalf's fireworks and end up doing the dishes as a punishment. The visual is funny, but it also gives the impression that very little time passes between that event and the moment when the four hobbits unite and head out for Rivendell.

The truth is, though, in The Fellowship of the Ring book, a whopping 17 years elapse between Frodo getting the Ring and Frodo leaving the Shire. Literally, he gets the trinket on his 33rd birthday and leaves the Shire on his 50th. So, for those of you counting at home, that inflates the amount of time that he has the Ring from a few years to nearly two decades. This goes a long way in explaining why he's so attached to the Ring right from the get-go, even though he does tell Gandalf in the book version that for the bulk of the time that he owned the Ring, "I have always kept it on its chain."

Why does Denethor act like an idiot?

While John Noble does a fantastic job portraying Denethor on the silver screen, if we're being honest, the cinematic version of the Steward of Gondor is given the most ridiculous role in the War of the Ring. He's arrogant to a fault, blinded by pride, and literally tells his men to "abandon [their] posts" and "flee for [their] lives" when he realizes that his city is under attack. Worst of all, he very clearly orders Faramir to attack Osgiliath when there's no question that he's going to be mown down by an army of orcish archers.

All of this mentally unstable behavior is so over the top that it begs the question – what the heck is going on? As we turn to the original text, we find some answers. It turns out that Tolkien does make Denethor an unstable individual. However, his poor judgment is much more nuanced in the books.

He isn't a mad tyrant openly trying to kill his son. On the contrary, while he does make his disappointment of Faramir clear, he convinces him to go out and defend the outer walls of the kingdom. It's a hopeless task but not a sure suicide mission. On top of that, the steward very actively tries to do his best to defend Gondor, even though he's lost all hope thanks to his communication with Sauron via one of the seeing stones (aka palantíri). The point is, Denethor is a pride-filled father and a hopeless leader, but in the books, he isn't a harebrained fool.

Are hobbits related to another race?

Hobbits are an interesting race of individuals that are native to Middle-earth and Middle-earth alone. They share similarities with men, dwarves, and even elves at times, which often leads to the question of whether or not Tolkien meant for them to be related to any of these people groups.

The answer is yes, they are related to one of them. To men, to be precise. At least, they're most likely related to them. Again, Tolkien left this one with a maddeningly almost-definitive answer. In the prologue to the book The Fellowship of the Ring, Tolkien spends a decent amount of time breaking down the history, ancestry, and culture of the Little People. In the middle of the breakdown, he straight-up states that, "It is plain indeed that in spite of later estrangement hobbits are relatives of [men]." While this is presented as an obvious fact, though, he also points out that "the beginning of hobbits lies far back in the Elder Days that are now lost and forgotten," adding that the relationship between hobbits and men "can no longer be discovered."

So, while Tolkien refuses to definitely state the connection, he all but declares that hobbits are a miniature version of the Big People. It's an interesting winner of the "who's related to hobbits?" sweepstakes, as halflings are repeatedly described as looking down (or is it looking up?) on men as lumbering fools that cause all sorts of havoc and disrupt their quiet little lives.

What happened to the dwarven rings?

Throughout both The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit movies, we see the various Rings of Power in action. We see the nine rings wielded by mortal men doomed to die. We see the three elven rings used to keep all that is good and holy intact. And, of course, we see the Ring, which serves as the focal point of the entire story.

But what about the seven dwarven rings? These are shown briefly at the beginning of The Fellowship of the Ring, and they're mentioned every time the Ring poem is recited. But that's about it. So, what happened to them? Did their owners lose them in their endless piles of gold and jewels?

Gandalf provides a bit of clarity on the subject in The Fellowship of the Ring when he hastily brings Frodo up to date on the long lore of the Rings of Power. He briefly mentions that, "Seven the dwarf-kings possessed, but three [Sauron] has recovered, and the others the dragons have consumed." This is partially confirmed at two different points. In the same conversation, Gandalf also states, "It has been said that dragon-fire could melt and consume the Rings of Power." Then, at the Council of Elrond, Glóin informs the group that a messenger from Mordor asked for the dwarves' help in hunting for the One Ring. The price offered in exchange? "Three rings that the dwarf-sires possessed of old."

Is the Witch-king stronger than Gandalf?

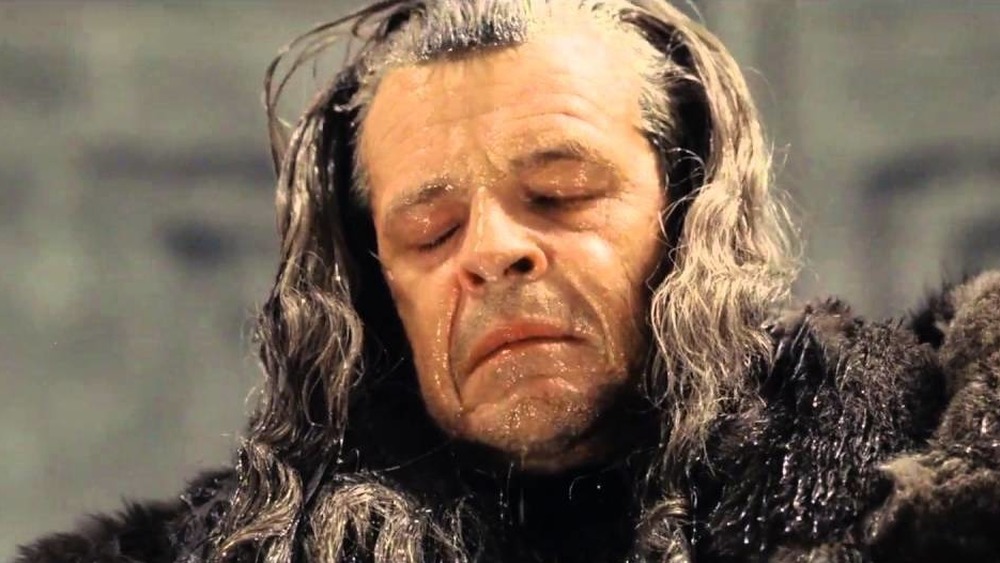

One of the biggest issues that the movies created with the original source material comes during a deleted scene from The Return of the King. Here, the Witch-king confronts Gandalf on the walls of Minas Tirith. During the course of events, the evil general literally explodes the wizard's staff and sends him hurtling to the ground.

The event is disconcerting, to say the least. Is Gandalf the White really weaker than one of the Nazgûl? While this is entering speculative territory at this point, we're comfortable claiming that this is absolutely an overstep by Peter Jackson. This isn't meant to be a knock against the Black Captain, either. The dude is about as bad as they come. He's thousands of years old, wields a Ring of Power, and is backed by the strongest being in Middle-earth — his master, Sauron.

However, we're not comparing him to a run-of-the-mill mortal or even an elven lord. This is Gandalf that we're talking about. The wizard is an angelic being that's been placed into a mortal body. He's older than time itself and is also secretly wielding one of the elven Rings of Power at this point. No matter which way you slice it, the Witch-king would never defeat Gandalf this easily. In the books, the two characters also come head to head, but before they can actually start to fight, the Rohirrim arrive and the Ringwraith retreats, taking any chance for a conclusive answer to the question with him.

Who is the oldest living creature in Middle-earth?

The question of "who is the oldest in Middle-earth?" is a really tough one. In a world full of immortal beings, the competition basically boils down to two characters: Treebeard and Tom Bombadil. The case for Treebeard being the oldest is pretty simple. In The Two Towers book, Gandalf calls Treebeard, "The oldest of the Ents, the oldest living thing that still walks beneath the Sun upon this Middle-earth."

As for Tom Bombadil, when the four hobbits visit the enigmatic character early in the book The Fellowship of the Ring, Bombadil tells them, "Eldest, that's what I am. ... Tom was here before the river and the trees; Tom remembers the first raindrop and the first acorn. ... He knew the dark under the stars when it was fearless — before the Dark Lord came from Outside."

While both characters seem to be put forward as "the oldest," we're going to give the edge to Tom Bombadil here for a few reasons. First, at the Council of Elrond, Bombadil is referred to as "Last as he was First," "older than the old," and "oldest and fatherless." On top of that, in a letter to a fan written in 1954, Tolkien refers to Tom Bombadil as "Eldest in Time." All of these subtle nods to Bombadil's ancientry make it easy to declare him the winner in what appears to be a very close contest.

Why does Legolas shoot Wormtongue after he stabs Saruman?

In the extended edition of the Return of the King movie, we see an unsettling scene where Saruman meets his doom via a mesmerizing fall off the tower of Orthanc. This happens after he's stabbed by Gríma Wormtongue, who turns on his abusive master in a fit of rage. This prompts a completely random act from Legolas, who fires an arrow at Wormtongue, killing the murderer because ... why?

The cold-blooded killing of Saruman makes sense. After all, Wormtongue's life has been ruined by the treacherous wizard. But why does Legolas then feel justified in slaughtering the backstabber, too?

The answer is that none of this actually happens in the books — or very little of it. Saruman and Wormtongue are actually released from the tower by Treebeard, and they travel to the Shire. There, they meet the hobbits when they return home and find Saruman's servants destroying their homeland. Eventually, Frodo and his friends get the upper hand and send Saruman and Wormtongue away once more. At that point, Wormtongue snaps, stabs his master to death, and tries to run off before he's mowed down by a line of trigger-happy hobbit archers. The scene makes much more sense in the books and doesn't paint Legolas as a cold-blooded killer who shoots people, vigilante-style.