Silk Road Review: A True Crime Story With Some Colorful Turns

No less an authority than Martin Scorsese has gone on record as saying that casting is "85 to 90 percent of the picture." If this is true, the rest is dependent on a script's ability to make the audience understand its characters' decisions. We've all seen plenty of films with amazing casts who respond to the film's events in frustrating, irrational, forced ways antithetical to anything any real person would do, torpedoing the whole movie.

The greatest strength of Silk Road is that its rationality is tight. It's anchored by two well-drawn characters, one supposedly "the good guy" and one supposedly "the bad guy," who make a series of decisions throughout the film that massively impact their lives and the lives of everyone around them, blurring those lines. True to life, every stumble down the hill of ethics is a baby step — sure, you may draw a line in the sand today, but next week, if money or fame or some other prize is within grasp, it's so tempting to move that line just one more inch. The result is a dynamic ride that is very easy to go along with.

Silk Road begins with a simple disclaimer: "This story is true — except for what we made up or changed." If you watch the film — and you most definitely should, as it's a riveting depiction of slippery moral choices and two men consumed by their repercussions — and you want more information, you can always go back afterwards and read the Rolling Stone article which serves as its source material.

If you've remained oblivious to the story this long, your best bet is to watch Silk Road first, then look up what's real and what's embellished afterwards. As a narrative film, much of the tension is dependent on the audience not knowing where it is headed, so if you've avoided (or don't recall) the 2013 headlines when the Silk Road site was shut down, read no further. Go watch the film, enjoy it, and come back. Don't worry, we'll wait.

So, how does this 'InterWebs' thing work?

The film tells the twisted tale of Ross Ulbricht, who in real life founded a company called Silk Road, determined to become the Amazon of illegal materials (largely drugs) using emerging technologies like Bitcoin and Tor to facilitate anonymity for its users. This is contrasted with the tale of Rick Bowden, a composite DEA agent with a troubled history who becomes obsessed with taking down Ulbricht and proving his old-school ways are effective against this cutting-edge crime lord. Looking at the story — drugs, feds, kids, large sums of money and murder hits — you can see why certain names and facts had to be changed for legality and expediency.

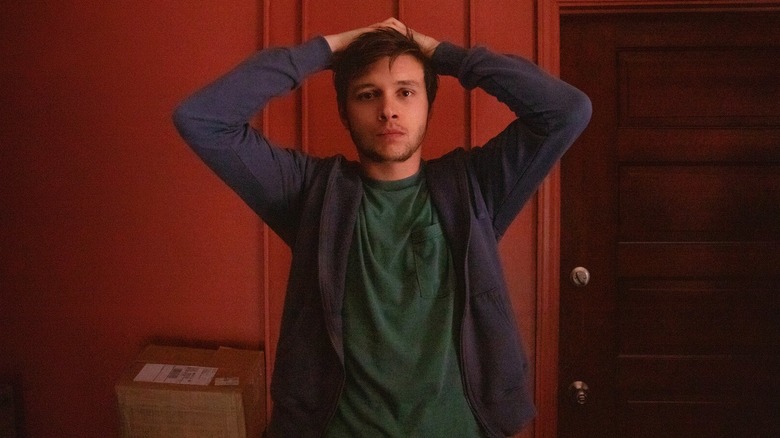

Bowden is brought to life by Jason Clarke (Chappaquiddick), depicting an officer on the edge, grappling with his own irrelevance; it's a performance that would have been right at home alongside Vic Mackey's crew on The Shield. Ulbricht is the kind of dismissive, overly confident hacker that Jimmi Simpson would've played 15 years ago; here he is portrayed by Love, Simon star Nick Robinson as an idealistic, tortured soul with a glaring blind spot in his libertarian extremes. The dismissive, overly confident hacker boss of a cybercrimes taskforce is, ironically enough, played by Jimmi Simpson.

The film has narrative bookends featuring a library sting operation and a "You might be wondering how I got here"-type flashback structure. We journey alongside Ulbricht as he goes from a hoodie/flip-flop-clad washout who speaks openly about his desire to "change the world" to the point where he is a hoodie/flip-flop-clad entrepreneur on the run whose site is raking in $833 a minute. Officer Bowden, meanwhile, begins his journey as he gets out of rehab, and we get vague details about a downfall involving undercover work in Puerto Rico, cocaine, a car crash, and a merciful department action that takes him off the streets and sticks him behind a desk to rot.

This is where the parallax plot points begin, as Bowden gives himself a crash course watching "Welcome to the Internet" videos and Ulbricht sits down in front of a computer and declares he's not getting up until he has taught himself to code. One character is at the beginning of a career, determined to change the world; the other has come to discover that his life's work has changed nothing, and now he's nearing the end.

This is when the film excels, blurring the supposed lines of good and evil as a virtual chase takes shape. Bowden gets just enough computer know-how to sniff out the Silk Road site, and becomes obsessed with taking down the anonymous owner who calls himself Dread Pirate Roberts. We see both men simultaneously struggle with the relationships in their lives, both grapple with the perceived incompetence of those around them, both get to the point where they're trying to stay one step ahead of the law.

There's a carrot-on-a-stick feeling in these dueling stories, as the viewer is led along a series of moral concessions — would you start a website if you knew how to make billions doing it? Is stealing from a criminal really stealing? There are never any huge leaps in logic, and as you follow along, don't be surprised if you feel somewhat complicit when both men look around and wonder: how did it come to this?

Much of this plausibility is due to Clarke and Robinson, and a supporting cast around them that is uniformly strong. The aforementioned Simpson, Alexandra Shipp (X-Men: Dark Phoenix) as Ulbricht's disapproving girlfriend, Katie Aselton (The League) as Bowden's put-upon wife, Darrell Britt-Gibson (Barry) as a halfhearted informant who has a hilarious, touching rapport with Clarke's gruff Bowden — and a special shout out to Paul Walter Hauser (Richard Jewell), who once again steals every scene he's in, this time as a couch potato drug kingpin who thinks he's got it made.

Great casting, and as Scorsese would say, it goes a long way towards making the film. The actors do a solid job bringing humanity to a script that sometimes has trouble connecting the dots, and other times skims over story beats that deserve deeper exploration — like when Ulbricht watches a news report about a young man who leapt to his death, high on drugs he acquired from Silk Road.

Yes, officer, these are what I used to create the website

Which brings us to another element that "makes a picture," and one that Silk Road sorely lacks. A great movie makes you finish it and immediately want to watch again. There are instantly memorable scenes, quotes, sequences. As compelling a ride as Silk Road can be, it really has none of that.

Since Jason Clarke and Nick Robinson are only together for what could generously be called one and a half scenes, the film can't help but feel like it wants to be a 21st century Heat. Sure, maybe it's unfair to compare Silk Road to such a masterpiece, but setting aside all the other virtues of Mann's crime epic, consider how that film is just so watchable. How every repeat viewing yields new lines, new moments, and thrills worth experiencing again and again.

Whether you're talking about the aforementioned The Shield, or cocky-kids-in-over-their-heads films like The Wolf of Wall Street or Rounders or even Boiler Room, they are much better constructed for repeat viewings. This film is content to say "Here's a solid story, go for the ride, and then we're okay if you never want to visit us again." This might be in large part due to director Tiller Russell, whose background is stuffed with true crime credits — Silk Road leaves you with the same aftertaste as one of those hot-for-a-minute podcasts that is riveting to listen to, but once you know how it plays out there's little reason to go back and listen again.

Ultimately, the two main characters in Silk Road are surrogates for the audience in a multitude of ways. We identify with their decisions, we are intoxicated by the money and power in their proximity, we dream of a supposedly better world where freedom is unrestricted and money problems are of no concern. But unfortunately, there's one other way the audience will identify with Ulbricht and Bowden: after their story has been told, you won't have much desire to ever re-live it again.