How Shawshank Redemption Is Different From The Book

When you finally get to see a beloved book adapted into a movie, it can be an incredibly bittersweet experience. There are always at least a few literary moments you longed to watched play out onscreen that didn't make the cinematic cut. Sure, it's always great to see some creative liberties, but there's a delicate balance to be struck between preserving the spirit of the original and breathing new theatrical life into the story for a sense of familiarity and discovery.

In many ways, the 1994 film adaptation of Stephen King's 1982 novella Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption hit the sweet spot. For the most part, the film impeccably preserves the dialogue that made Stephen King's story such a classic to begin with. But in many ways, it improves on the original tale in a few heartwarming moments. It combines disparate characters from the book into consummate players onscreen, rather than entirely omit the personality quirks that captured life in its smallest, most strangely intimate moments. Plus, it offers more closure for a handful of characters, for better or for worse.

So even though the film is aligned with the book almost minute for minute — with both taking about 2 hours and 20 minutes to complete — there are some crucial differences that separate the two. From character deaths to the ending itself, here's how The Shawshank Redemption is different from the book.

(Warning — there are spoilers below.)

The Warden's demise was never in the book

One of the most reliable patterns employed by the Shawshank movie is that of giving its characters significantly more dramatic endings than they enjoy in the novella. For example, the story of the prison warden, the corrupt and Bible-toting Samuel Norton (Bob Gunton), has one of the most climactic conclusions of all.

Throughout the movie, he's been a source of antagonism for Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins) and his cohort, but the relationship is exceedingly complex. Norton takes a liking to Andy and allows him special privileges, from creating an entirely new "library assistant" position for him as a form of protection and morale boosting to personally mailing Andy's letters to the Senate, requesting funding for a new library.

The flipside of the interest and favoritism, however, are his transactional expectations. Andy is in charge of "cooking the books" on the warden's various illegal schemes and dealings. In a way, it turns out that he was right to control Andy so meticulously because Andy does indeed hold the keys to the warden's "judgment."

After his escape, Andy releases the details of the scandals, and when the authorities come for Norton, he shows that he's too weak to endure the torturous experience he himself has presided over. He commits suicide rather than be sent to prison. In the book, he simply resigns after a nervous breakdown, but the movie's depiction is perhaps an even more insightful reflection of the warden's false righteousness.

The warden has a greater presence in the Shawshank movie

The warden's memorable movie ending makes a bit more sense when you consider how much more significant the character is in the film than in the book. In a way, he earns his drama. In the book, three wardens serve in the position at different times through the decades, making any individual warden much less integral to the plot. But the presence of the same warden throughout Andy's entire tenure at Shawshank in the movie — and the relationship that develops between the two — much more convincingly calls for a dramatic demise.

Though he's certainly an adversarial force in the book, Warden Norton is the main antagonist in the film, and his actions drive much of the plot and the development of Andy's character during his time in prison. Ultimately, the warden isn't being genuinely kind to Andy, only rewarding him when he complies and punishing him viciously when he steps out of line. He intimidates and manipulates Andy and even sacrifices the lives of others in order to keep Andy in prison, using the former banker's expertise to cover up hundreds of thousands of dollars' worth of corruption. Of course, it's this directive that allows Andy to create the fake identity he eventually uses after he escapes from prison.

The luck of the Irish

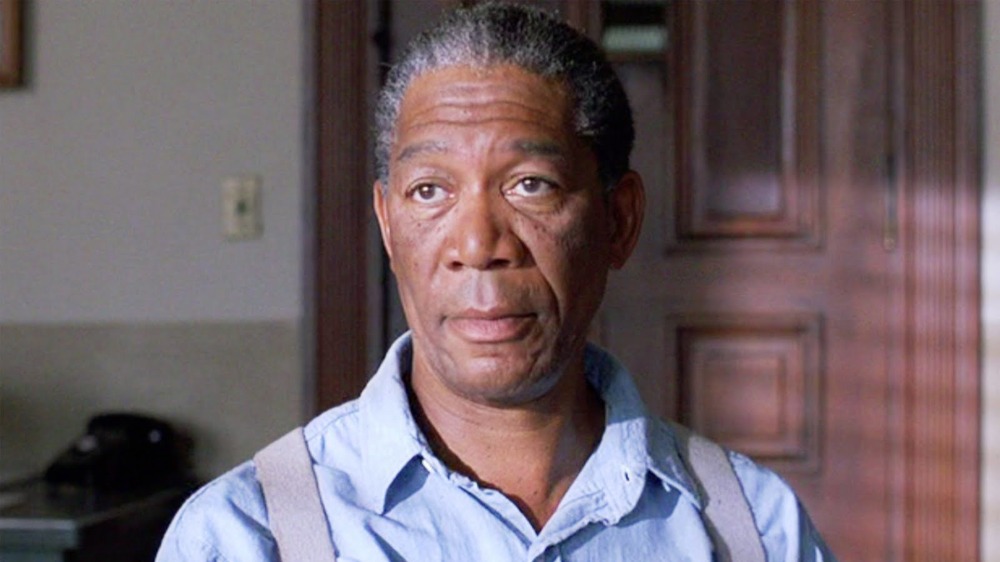

If you chuckled when Andy asked Red the origin of his nickname and Red responded, "Maybe it's because I'm Irish," perhaps it just seemed like a goofy joke for Morgan Freeman's character to make. But if you're familiar with the source material, you'll realize this as yet another instance of the screenplay sticking close to the original dialogue.

Red's character was Irish in the novel, not African-American. The sought-after Morgan Freeman even shied away from the role at first because he read the novella and thought, "I can't play an Irishman." Of course, he didn't play one, as the movie creatively worked around including the line by passing it off as a joke. Instead, he made the part his own and even earned an Oscar nomination for it.

Another small but significant difference between Red's trajectory in the novel and the film is that he finds the box by searching himself in the book, with less direct guidance from Andy's clues than he has in the film. In fact, in the book, he spends weeks searching for the box under the volcanic rock near the old stone wall from Andy's years-old description, all during the downtime from his shift bagging groceries at the store. In the film, he takes a ride out into the country, and though he has to walk around for a while, he locates the box with relative ease. Or maybe it's just luck — he was due for some.

Some beautiful moments are uniquely cinematic

While the Shawshank film strayed remarkably little from its source material, it did include some extra moments that were uniquely suited to the medium and wouldn't have played nearly as well on paper. It's hard to imagine how one could add much of consequence to the original story, but director Frank Darabont managed it beautifully several times.

In one of these scenes, Andy has just received a slew of responses and donations regarding his request for funding for an expanded prison library. The new materials — funds, used books, vinyl records, and more — have piled up in the prison's office, and Andy has been directed to empty it out before the warden returns. Instead, he locks himself in and places a classical music record on the vinyl player, turning on the prison intercom to blast it over the loudspeaker for the other inmates.

The entire prison stops what they're doing in order to listen, and "for the briefest of moments," Red says that "every last man in Shawshank felt free." Andy later explains that music is so significant because it exists inside your head and can never be taken from you. The unique advantage of film, which Darabont used to great advantage in this moment in particular, is that it can be a conduit for this special gift that can never be taken away.

Shawshank's guard is quite different in the book

Captain Byron Hadley (Clancy Brown), like the warden and others, is also an essential character in the film who didn't play as significant a part in the novel. In the 1994 movie, Hadley gets arrested for his part in the crimes committed at Shawshank, allegedly crying like a baby when they take him in. In the novel, however, the guard doesn't do nearly as much for the plot and simply disappears from his post midway through the story (rather than sticking around to get arrested at the end) after suffering a heart attack.

Before the situation with the warden escalates to massive fraud, the death of Tommy, and the continued and worsening abuse of Andy, the movie's version of Byron Hadley is one of Andy's chief adversaries. While other guards take a shine to Andy and treat him with some measure of respect and even genuine kindness, Byron is constantly a stick-in-the-mud at best and a tormentor at worst. As with the warden, it's a little bit hard to believe that he remained at his post for over 20 years, but it's not impossible and makes for a more convincing rivalry and a more satisfying eventual defeat.

Andy was written as a small man ... but Tim Robbins is not

The closeness of the film to its source material was counterbalanced by some of the casting choices. Like Red, who was cast as Black rather than Irish, Andy himself looks a little different onscreen than fans of the book might expect. In the novel, Andy is written as a more diminutive man — short, well-kept, and exacting.

His fastidious nature, at least, is evident in his behaviors and interactions, from his hobby of collecting and whittling rocks to his success as an accountant of sorts for the entire prison staff. He even creates a seamless fake identity for himself out of thin air with the limited resources available to him in prison.

But in terms of stature, Andy as played by the 6'5" Tim Robbins looks a lot different from the way he's described in the book, and sticklers can certainly argue over any metaphorical significance to his character. Less of a literal underdog, perhaps? It's undoubtedly fascinating to think of a small and unassuming man raging against his own helplessness (both by tunneling through a prison wall and by allegedly murdering his wife and her lover).

However, the fact remains that, while the story maintains a remarkably large part of its integrity in the film, more liberty (no pun intended) was taken with the casting because it was more about who could best portray these compelling characters and less about what they looked like while they did it.

There's no reunion at the end of the Shawshank book

The conclusion of the Shawshank film is one of the most poignant ways in which the adaptation adds something to the story by straying from it. In the book, we don't get to see Red walking toward Andy on the shore of the Pacific Ocean, both of them fugitives but both of them free. Instead, we just get the line where Red says he hopes he will see his friend again.

You could argue that leaving it open-ended like the novella does, rather than the explicitly happy ending offered by the film, is a more accurate representation of the nature of hope. But Red and Andy have already lived through enough open-endedness. It was open-endedness that proved too much for Brooks' (James Whitmore) "institutionalized" mind, as used to the prescribed roles and rituals of prison life as he was, and it almost overtook Red's as well.

Though the future remains exhilaratingly uncertain, the two friends nonetheless find in each other something concrete to place their hope in, something as definite and durable as stone. It's not the grey and unforgiving stone of a prison's walls but that of a volcanic rock that loyally guards the promise of a new life.

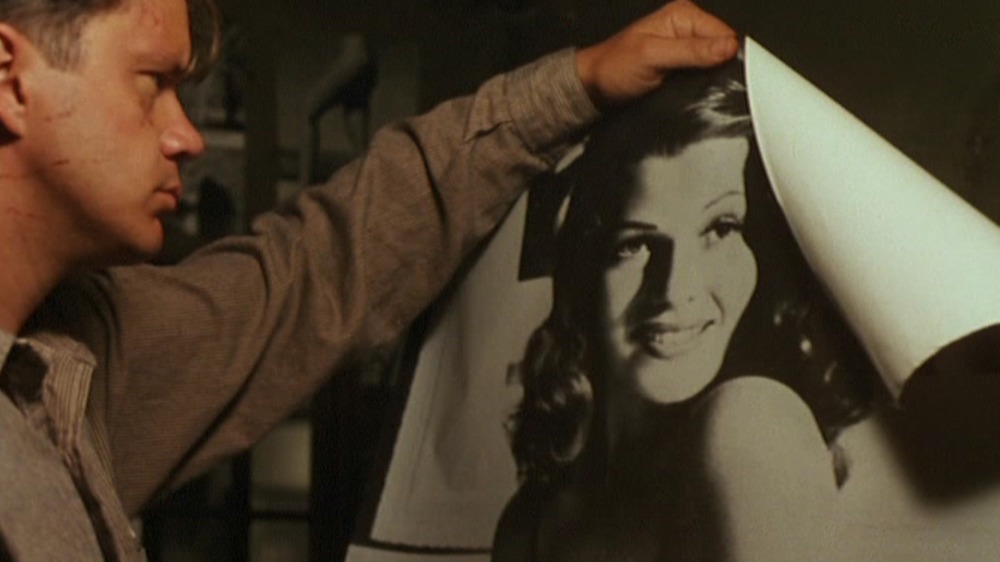

The significance of the Rita Hayworth poster

The novella is entitled Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption, and this title is significant partly because Rita Hayworth's is the first poster Red gives Andy in the novel, and they become friends afterward. In the film, however, the poster of Rita Hayworth is requested by Andy after the two are already friends.

It may not seem like that big of a deal, but the actress is featured in the novella's title for a reason. She represents the beginning of the friendship that forms the foundation of the story. Changing the order of events in a seemingly inconsequential way nonetheless slightly undercuts this meaning. The actress is so significant to the original story that Darabont actually received audition materials from some hopefuls for the part of Rita Hayworth (which didn't exist), despite removing her name from the title of the adaptation.

It's also interesting to note that in Andy's multiple decades at Shawshank, the poster on his wall changes only twice in the film, from Rita Hayworth to Marilyn Monroe and finally Raquel Welch as the sole witness to Andy's escape. The poster changes multiple times in the novel. The pin-up women featured in the novel include Rita Hayworth, as well as Hazel Court and Jayne Mansfield and, at the time of Andy's escape, Linda Ronstadt.

Bogs is a much bigger character in the film

Like the rotating, less-consequential guards and wardens of the novel, the Sisters in the book are combined into fewer, more central villains for the movie. They're still depicted as a gang with multiple members who perpetrate Andy's harassment, but the locus of the aggression lies with Bogs Diamond (Mark Rolston), a character who's only mentioned once or twice in the novel before getting transferred and disappearing.

Bogs' role is much bigger in the film because he almost single-handedly does the tormenting that Andy endures from multiple members of the Sisters in the book. In terms of economical film production, it makes sense to consolidate this rivalry. The confrontations hit harder, and it increases our sympathy for the protagonist and our sense of the hostility of prison life.

In keeping with his exaggerated influence, Bogs' ending also makes more of a mark — literally. In both the book and the movie, he's transferred out of the prison. But in the film, it's only after he's been beaten to a pulp by the guards after assaulting Andy.

Brooks' ending is vastly different

As with characters like Boggs, Brooks is only mentioned in passing in the book, and his inclusion and expansion in the film speaks to Darabont's eye for the quirks and moments that define what it is to be human (which is what Andy and his fellow inmates themselves are trying so hard to cling to). The baby crow in his pocket is one such quirk, and we get to see him blossom into a full-fledged character. We're allowed to get invested in his story.

And that's why seeing him finally get released in old age and take his own life, unable to adapt to the strange and "hurried" world that has moved on without him on the outside, hits so hard. That's especially true when compared to his death from old age in the book. We get to know Brooks so much more intimately in the film, and through him, we also get a glimpse into just how ingrained the prison way of life becomes and how great a leap it can be from rehabilitation to reintegration.

Andy is suicidal in the book

On the evening of Andy's escape, his friends are quite literally up all night worrying about him. Red remarks in the voice-over that, even for the endlessly dragging prison nights, that was the longest night of his life. The group is worried for Andy because they believe he may intend to kill himself. He'd been speaking strangely to Red about the future, dying, and a mysterious object he's left for Red, almost in the sense of "making arrangements" as one might do near the end of their life. Then it comes out that he'd asked another inmate earlier for a six-foot-long rope.

It all adds up to a pretty worrisome set of behaviors and the implication that Andy may be planning to take his own life. So when he fails to show up outside his cell for the count the following morning, the audience and all of Andy's friends naturally have a pit in their stomachs, wondering at his fate.

But this moment would've been even more charged if we'd had the background information we get in the novel. Here, Andy is actually suicidal. He mentions this as an explanation for owning a gun, and knowing this would've heightened the tension in this moment exponentially, and it would've been motivating information for much of Andy's attitude and behaviors. For whatever reason, however, it's left out of the movie.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

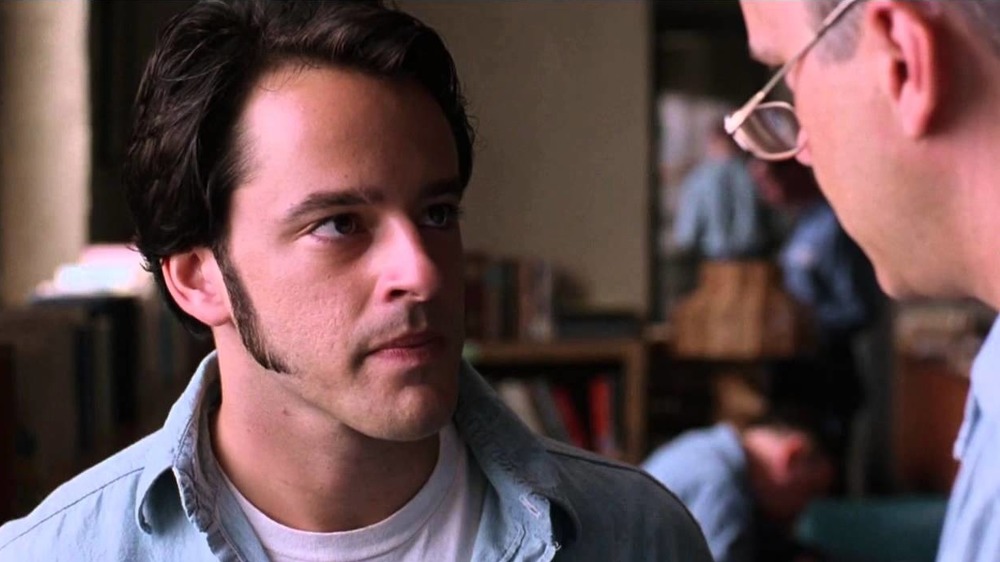

Tommy's fate in the Shawshank movie is much more dramatic

If Warden Norton's looming presence throughout the decades wasn't enough to cement his antagonism in the audience's eyes, what he does to Tommy (Gil Bellows) in the movie seals the deal tenfold. But fans of the movie may not be aware that Tommy actually lives the book. They just transfer him to another prison in order to prevent him from revealing his sensitive information.

What information? Well, as luck or coincidence or hope would have it, Tommy has been incarcerated all over the Northeast, and one night, one of his former cellmates was bragging about how he did a robbery job on some fancy golf pro who put up a fight, so he killed him and the girl he was with. And best of all, the authorities pinned the murder on the woman's distraught husband! This is, of course, Andy Dufresne, and the tale is the key to his innocence.

The only problem is that Andy has become a tremendous asset to Warden Norton. All of the corrupt man's schemes rest on Andy's "accounting" expertise. If Andy were to be exonerated and released, the warden would have a much harder time running his scams. So, the warden lures him outside and then has him shot under the pretense that he was trying to escape. It's the cold and calculating move of a real villain, not a minor antagonist. Tommy was sacrificed to create the film's more compelling villain.