The Untold Truth Of The Philadelphia Experiment

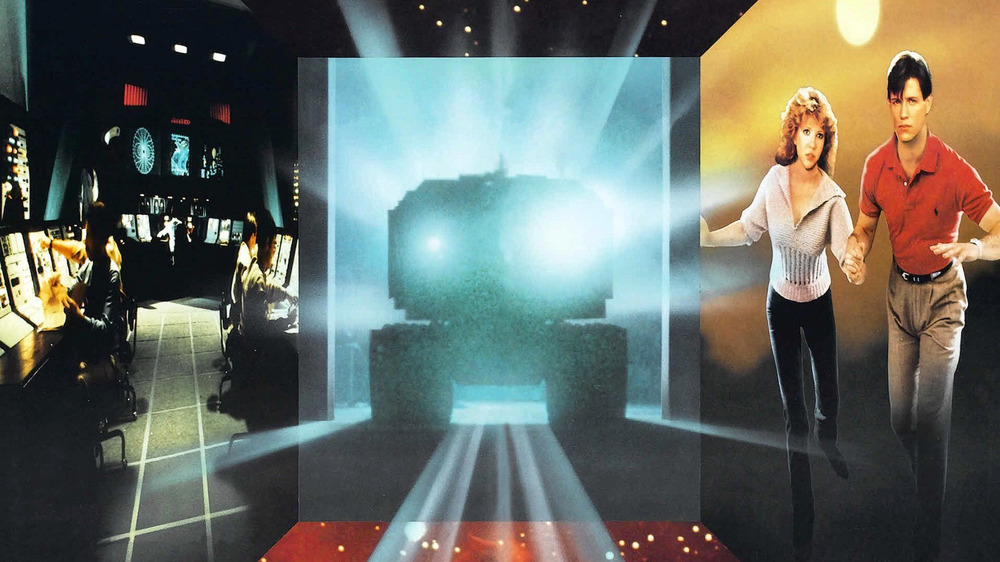

The 1984 film The Philadelphia Experiment is a romance, a war-time period piece, a time-travel movie, and depending on who you ask, is "based on actual events." Released under the auspices of Roger Corman's New World Pictures, known for its exploitation flick ethos, the film bears all the outward hallmarks of a high-concept b-movie, yet offers ambitious storytelling that aims higher than it needs to.

The film features Michael Pare, a young star continuing his rise after roles in Eddie and the Cruisers and Walter Hill's Streets of Fire. Appearing in their third film together, actors Nancy Allen and Bobby DiCicco also play pivotal parts.

Behind the scenes, several production changes suggest that this could have arrived as a much different movie than we know today, with more of an emphasis on horror and no romantic angles at all. A famous director was asked to helm the film but passed. On paper, if not in a military harbor near you, there's even a scientific theory to back up the wild MacGuffin that drives the movie's plot.

This is the untold truth of The Philadelphia Experiment.

Actual events in air quotes

"The Philadelphia Experiment" is an urban legend about a U.S. Naval experiment that purportedly took place in 1943 at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard in Pennsylvania, with the U.S. Navy destroyer escort USS Eldridge being rendered invisible to detection systems.

The tides of World War II had turned with the surrender of Italy to the Allies. With a sense that Germany was on the ropes, there was a great desire for the U.S. to shore up the gains the Allied forces had made. If they could get war craft into enemy waters without being seen, bringing with them the advantage of surprise, the war could end in short order. A ship with a cloaking device onboard could do the trick.

One problem: it's not true.

In 1955, writer and astronomer Morris K. Jessup purportedly received letters from unknown sources describing the experiment. Known for his belief in the supernatural and extraterrestrial, Jessup published books including The Case for the UFO (1955), The UFO Annual (1956), and The Expanding Case for the UFO (1957).

According to David Ritchie's 1994 book UFO: The Definitive Guide to Unidentified Flying Objects and Related Phenomena, Jessup claimed to have made a breakthrough regarding the Philadelphia Experiment on April 19, 1959. Just one day later, he was found dead in his car from carbon monoxide poisoning. The death was ruled a suicide, although conspiracy theorists believed he was silenced to keep from revealing things he was not meant to know.

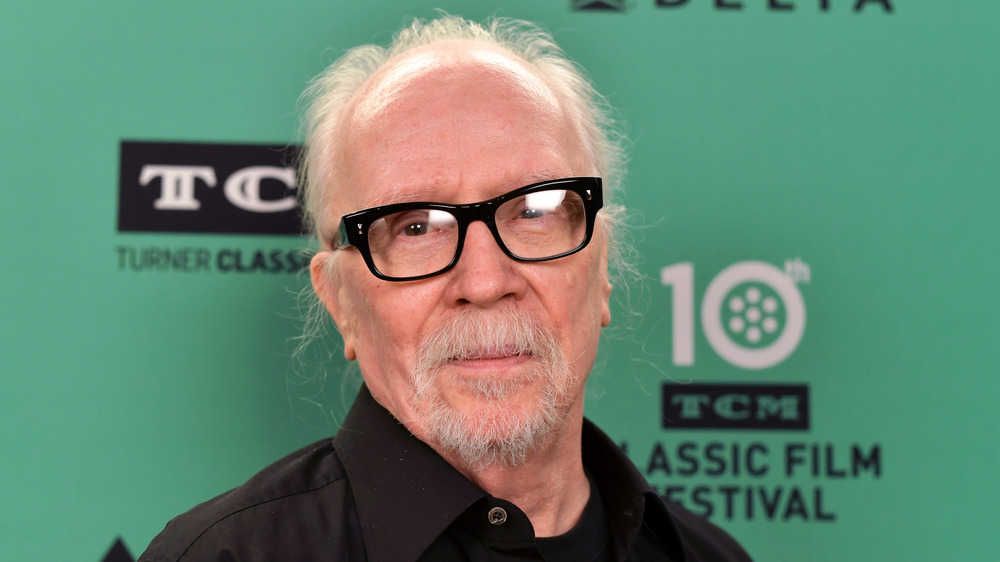

John Carpenter's Philadelphia Experiment

The movie we know today as The Philadelphia Experiment could have been far different. It started as a script written by horror film icon John Carpenter, who was taken by the legend. In an interview, Carpenter said, "Great shaggy dog story. Absolute bull****, but what a great story. While I was writing it, I couldn't figure out the third act. A friend suggested the revenge of the crew against the people who put them there, but I thought it was too much like The Fog. Absolute bull****."

It is unclear how much of Carpenter's original story made it to the final shooting script. What eventually made it to the screen was a time-travel story wherein two sailors involved with the experiment are plucked off of the USS Eldridge in 1943 and deposited in 1984. Romantic elements between one of the sailors and a good Samaritan were added in later drafts.

Carpenter was given an Executive Producer credit, but did not get a screenwriting or story credit for The Philadelphia Experiment.

While it might seem strange that Carpenter would simply relinquish a script this way, it was not unprecedented. In the mid-1970s, he delivered a treatment and two drafts of a screenplay titled Eyes to Columbia Pictures. The script went through several revisions, ultimately arriving in theaters in 1978 as The Eyes of Laura Mars, directed by Irvin Kershner (The Empire Strikes Back).

Director Stewart Raffill: pirates, wormholes and aliens

The Philadelphia Experiment wound up being the second 1984 effort for director Stewart Raffill, following the sci-fi comedy The Ice Pirates.

It is not uncommon for a director to take a pass at the script to align it with his or her vision, nor is it uncommon for a script to have many other writers involved. Raffill is an uncredited screenwriter for The Philadelphia Experiment. He re-wrote the screenplay to include a love story between the lead characters while also toning down the science-based exposition. Other writers on the project besides John Carpenter and Raffill included Wallace Bennett and Don Jakoby (Lifeforce, Arachnophobia), who received story credits, while Michael Janover and William Gray (The Changeling, Prom Night) earned screenplay credits.

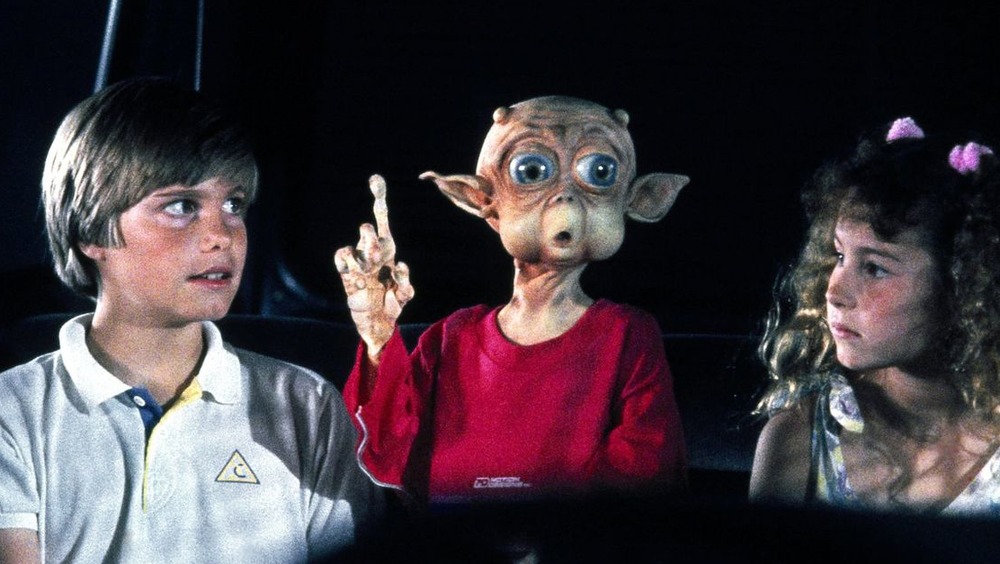

More consequential to pop culture, perhaps, is Raffill's follow-up feature, the 1988 movie Mac and Me. If you do not recognize the name, this is the thinly-veiled E.T. homage mercilessly teased by actor Paul Rudd on numerous appearances on The Conan O'Brien Show.

The cast of The Philadelphia Experiment

Leading the cast was Michael Pare, whose previous star turns included Eddie and the Cruisers and Streets of Fire. Joining him were Nancy Allen and Bobby DiCicco, who were castmates in two films before The Philadelphia Experiment: Steven Spielberg's 1941 (written by Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale, of Back to the Future fame) and I Wanna Hold Your Hand (co-written and directed by Zemeckis).

Pare and DiCicco play two ill-fated sailors on board the USS Eldridge during the experiment who are sucked into a time vortex, winding up in the '80s on the grounds where a military installation has suddenly vanished. Allen plays a bystander who helps the two (after being carjacked by them), all the while being pursued by the U.S. military.

Miles McNamara and Eric Christmas play Dr. James Longstreet (in 1943 and 1984, respectively). Longstreet is the scientist behind the prototype cloaking device. Keen-eyed viewers will also spot character actor Stephen Tobolowsky ("Ned Ryerson" from Groundhog Day) in one of his earliest roles as an assistant on the experiment.

A long, strange trip

The central conceit of The Philadelphia Experiment's plot is the time vortex which has ripped the USS Eldridge and a military town in the Nevada desert out of their respective eras. The cause of this is the cloaking technology developed by Dr. James Longstreet who tempted fate once in 1943 during the experiment and then again in 1984, having not learned his lesson the first time. The technology has created a start and endpoint for the time vortex, bridging a Philadelphia harbor and a Nevada town, and trapping both in the middle of the wormhole.

One can make strong parallels between the Longstreet character and that of John Hammond, the eccentric entrepreneur from the first two Jurassic Park films. Both characters display unbound hubris that leads to disastrous results. In other words, the characters exemplify the admonition given in the latter film: "Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn't stop to think if they should."

The time travel narrative device has found its way into many different forms of pop culture, from A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court to multiple episodes of the original Star Trek series to the Back to the Future series. The unique fingerprint The Philadelphia Experiment leaves on the trope is that the main protagonist is dragged into the future and not the past.

The science of The Philadelphia Experiment

Are wormholes possible? Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity says that space and time are inextricably tied and are, in fact, different descriptions of the same thing. A broad example is when you look up at the stars at night. The light you see from those stars was cast a very long time ago, and you are essentially looking into the past when you view them.

Further, any presence of mass, like the planets themselves, or energy will warp the fabric of space-time. That warping creates folds that can be "torn" and "patched," facilitating shortcuts between point "A" and point "B." These are wormholes. Problem is that they're only theoretical, with the math only suggesting their feasibility right now.

The first kind of wormholes to be theorized were Einstein Rosen Bridges, which describe black holes as portals to parallel universes. However, such bridges would be highly unstable, and if it did not collapse upon entry, the pathway between endpoints would take a very long time to traverse — hardly a conventional shortcut.

What does this have to do with The Philadelphia Experiment? Well, in director Stewart Raffill's script rewrite, the love story between Michael Pare and Nancy Allen's characters was added, and science-based exposition was toned way down. Its absence doesn't harm the story. In fact, had it been included, it likely would have slowed down the narrative. But if the question is "Are wormholes possible?" the answer is "yes," at least on paper.

Urban legends

The genesis of The Philadelphia Experiment lies in the urban legend of the USS Eldridge and the debate over whether the incident actually occurred or not. It is not the only example of a work of fiction relying on such anecdotes with sketchy provenance.

The most famous of these would be Men in Black (1997), which relied heavily on the mythology of men dressed in black suits claiming to be government agents and using intimidation to silence UFO witnesses. Although the films starring Will Smith and Tommy Lee Jones are the most widely-known examples, there are several instances both before and after these using the same themes. The X-Files episode "Jose Chung's From Outer Space," for example, featured Jesse Ventura and Alex Trebek as men in black.

Fiction abounds with stories about wormholes, the time-space shortcuts that allow the Millennium Falcon to jump through hyperspace, the Enterprise to go to warp speed, and Doctor Who's TARDIS to move from Earth to Gallifrey. The creation and manipulation of wormholes is the crucial mechanism for the videogame Portal.

So it is with The Philadelphia Experiment. Dr. James Longstreet has essentially created a black hole in 1943 and another in 1984. Caught between these is a rift in space-time where both the USS Eldridge and the military town are essentially held hostage.

Life after the Experiment

The American Film Institute Catalog suggests that the budget for The Philadelphia Experiment was $9 million. Its worldwide take as reported by Box Office Mojo was $8,103,330. Measure that against the 10th highest-grossing film of 1984, Splash, with a worldwide gross of $69,821,334, and it becomes clear that the film underperformed.

Rotten Tomatoes only has 10 reviews logged, with a lowly 50% rating, but there is public goodwill for the film. Although tame by Roger Corman/New World Pictures standards, it retains the renegade spirit found in the studio's other efforts. One could imagine the studio heads saw it as a kind of Terminator-in-reverse with the protagonist arriving from the past instead of the future. It is a movie that brings its a-game to a b-movie milieu.

As an early entry in the videocassette rental boom of the 1980s and a stalwart of cable television, the movie earned enough name recognition to merit a sequel ... sort of. Philadelphia Experiment II, released in 1993, featured a different cast and crew. The SyFy network offered a made-for-television remake in 2012. Michael Pare returned in this version, but in a different role.

In the end, The Philadelphia Experiment has become a cult favorite thanks to audiences connecting with concepts that punched above their weight and with the underlying romance that was tacked on at a very late stage. It's a film that was never likely to transcend its limitations but earns points for earnestly willing to make the attempt.