The Untold Truth Of Peanuts Holiday Movies

Peanuts began as quietly, modestly, and unassumingly as its lead character, good old Charlie Brown, not showing any sign that it would turn into a cultural juggernaut as flashy and popular as its other main character, an imaginative beagle named Snoopy. In the late '40s, Li'l Folks debuted in a Minnesota newspaper called the St. Paul Pioneer Press. The comic was the creation of local cartoonist Charles Schulz, and three years later, he told it to a syndicate, which renamed it Peanuts and placed it in just seven papers. By the end of the 1950s, Peanuts was huge, appearing in around 2,600 newspapers and spawning lines of toys, greeting cards, and anthology books.

So, it only made sense to give the people what they wanted and expand the Peanuts empire to television in the mid-1960s. Over the decades, more than 40 Peanuts specials hit the airwaves, led by producer Lee Mendelson and director Bill Melendez. The ones about holidays resonated the most, and it's a tradition among countless families to watch them each and every year. But believe it or not, there are several surprising stories about these classic short films. From jazz music to behind-the-scenes heartbreak, here's the untold truth of the Peanuts holiday movies.

The origins of the Peanuts holiday movies

Prior to the development of A Charlie Brown Christmas, nonfiction film producer Lee Mendelson had started work on an unaired TV documentary called A Boy Named Charlie Brown. It was supposed to be something of a companion piece and a follow-up to Mendelson's previous documentary, A Man Named Mays, a chronicle of baseball legend Willie Mays. As Mendelson told Stanford Magazine, "What came into my mind was, 'You've just done the world's greatest baseball player, now you should do the world's worst baseball player, Charlie Brown.'"

Peanuts creator Charles Schulz agreed to participate, and Mendelson made his movie, which mixed live-action footage of the cartoonist with animated sequences starring the familiar characters. Then Mendelson had another problem. He needed musical score, particularly for the animated bits. As he thought it over, he drove over the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, and the Vince Guaraldi Trio's "Cast Your Fate to the Wind" — a jazz instrumental that had become an unlikely crossover hit on the pop chart — came on the radio. Soon after, a local jazz critic got Mendelson in touch with the eponymous musician. "Vince and I met a few days later, and within a few weeks, the song 'Linus and Lucy' was born," Mendelson said in The Art and Making of Peanuts Animation. "It went on to become our theme song for the next half century."

Charlie Brown owes his TV incarnation to Coke

In early 1965, John Allen, an executive in charge of the Coca-Cola account at major New York advertising agency McCann-Erickson, was informed that his client wanted to increase its television presence by sponsoring a kid-friendly Christmas special. Allen's thoughts turned to Peanuts, as Time had just published a cover story about Charles Schulz and his creation. He'd also been present for the sole public screening of the documentary A Boy Named Charlie Brown at the San Francisco Advertising Club, and so he put in a call to the documentary's producer, Lee Mendelson, and asked if he'd ever considered making an TV episode-length Peanuts holiday special.

"I said, 'Absolutely!'" Mendelson recalled to Stanford Magazine. He hadn't really, but he told Allen he was all in... before consulting Schulz, who'd previously resisted numerous adaptation offers. "It was a Thursday, and they asked if I could send the outline to them by Monday. Well, I posed Schulz and told him that I had just sold a Charlie Brown Christmas show. He asked which show, and I told him, 'The one we're going to make an outline for tomorrow.'"

Coca-Cola authorized production to begin, and Mendelson and Schulz got to work. They hired veteran Disney animator Bill Melendez, who'd made some Peanuts-themed Ford commercials in 1959 (and the cartoon sequences for A Boy Named Charlie Brown), whom Schulz liked because he felt he accurately captured the simplicity, style, and tone of the Peanuts strip.

TV executives hated A Charlie Brown Christmas

Not only did Lee Mendelson agree to A Charlie Brown Christmas before consulting Charles Schulz, but according to Smithsonian Magazine, John Allen, the McCann-Erickson ad man representing Coca-Cola, hadn't yet sold the idea to a network when he approached Mendelson. CBS, for example, eschewed animation and event television under the leadership of president James Aubrey, who thought cartoons were for Saturday mornings only and that specials ruined audience viewing patterns. However, CBS fired Aubrey in February 1965, and the proposal for A Charlie Brown Christmas arrived from Allen just two months later. That's when scrambling executives bought the pitch, if only because Schulz was a close friend of CBS CEO Frank Stanton.

Months later — mere weeks before A Charlie Brown Christmas had been scheduled and advertised — CBS executives viewed the special. "They just didn't like the show," Mendelson told MediaPost. "They thought it was too slow, they didn't like the jazz music so much on a Christmas show — in other words, these were all creative things that they didn't like." Indeed, after a private screening with director Bill Melendez, Mendelson didn't have high hopes, either. "Bill thought we had really missed the boat." But the special was done, so they had to turn it in. Plus, it was set to air, and CBS had to run it. After it did broadcast on December 9, 1965, all fears dissipated — about half of all American households tuned in to watch A Charlie Brown Christmas.

How Charlie Brown brought religion to primetime TV

One major element that set A Charlie Brown Christmas apart from other mainstream television shows, particularly animated ones, was its overt religious message. In his journey to understand the true meaning of Christmas, Charlie Brown listens to a monologue from Linus, who recites a passage from the Bible that describes and explains the importance of the birth of Jesus Christ — historically and religiously a major impetus of Christmas.

The holiday is also a secular celebration, and Christmas-oriented programming tends to reflect that point of view, emphasizing the coziness and togetherness of the Yuletide season. However, CBS executives weren't worried about the Christian tone. "They had no problem with the religious aspects," producer Lee Mendelson told MediaPost. Some people who did? Mendelson himself, as well as director Bill Melendez. When they were crafting the show's plot, Schulz told his collaborators that he planned to have Linus read a Bible passage. "And Bill and I looked at each other, and Bill said, 'You know, I don't think animated characters have probably ever read from the Bible.'" But it was very important to Schulz to include that. In fact, without that element, he didn't see the point in making the special at all.

How Peanuts killed metallic trees

A Charlie Brown Christmas has consistently aired on broadcast television for more than five decades, a testament to its timeless themes and near-universal appeal. But the thing was produced in 1965, and so there are some elements that haven't aged well. The part that's probably most baffling to latter-day audiences? The show's depiction of, and disdain for, aluminum Christmas trees.

In the special, Charlie Brown sets out to find a good tree for the Peanuts gang's Christmas play. "Get the biggest aluminum tree you can find, Charlie Brown, maybe painted pink," Lucy suggests. He gets a real tree, instead (albeit a tiny and meager one), as the metal ones leave him cold and nonplussed, particularly when he touches one, and it emits a loud "thunk." Believe it or not, aluminum trees were a real thing, although the one in the Peanuts special is a bit of exaggeration. In real life, they looked like colored aluminum foil, not a solid hunk of metal.

While realistic-looking trees made of artificial materials are commonplace today, these mid-century, aluminum evergreens are hard to find. And the reason why is because A Charlie Brown Christmas killed off their popularity. According to the Great Falls Tribune, aluminum trees debuted in 1959, and they were a massive holiday fad, peaking with production of 150,000 units in 1964. Then in 1965, A Charlie Brown Christmas aired to immediate and massive popularity. The special's outright disdain for these metal firs, and by associating aluminum trees with the commercialization of Christmas, did them in. By 1970, industry leader Aluminum Specialty Company stopped making the product altogether.

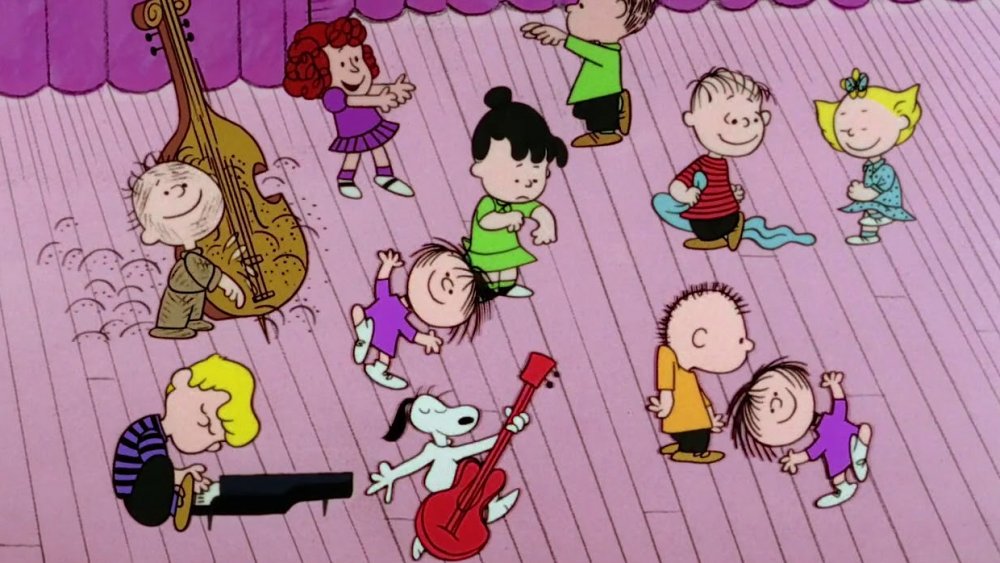

Why Peanuts holiday specials sound different

Up until the late '50s, kids voicing kid characters wasn't widely done in animation. Usually, adults took the roles. In 1959, animated TV ads experimented with child actors, including a Peanuts-themed campaign for Ford Motors. Bill Melendez directed those commercials, and when he got the Charlie Brown Christmas gig, Charles Schulz mandated that he once again hire kids. As a result, Peter Robbins played Charlie Brown in the ad and the Christmas special.

"I was fed half a sentence by half a sentence by Bill Melendez," Robbins said in The Art and Making of Peanuts Animation. "He gave me the inflections that he wanted." Then, actor Todd Barbee took over the role for A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving. "One time they wanted me to voice that 'AAAAAAARRRRRGGGGG' when Charlie Brown goes to kick the football and Lucy yanks it away," Barbee told Noblemania. He just couldn't nail the line, and after more than two dozen takes, "an adult or a kid with an older voice" subbed in.

Cathy Steinberg voiced Sally Brown in both A Charlie Brown Christmas and It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown, a job she landed because producer Lee Mendelson was a neighbor. She was only four when she got the gig. "I remember not being able to read the script for the Christmas show because I was too young to read," Steinberg told Noblemania. However, she had a different issue during production of the Halloween show. After recording half of her lines, Mendelson got word that Steinberg was about to lose a front tooth, and that when she did, she'd acquire a lisp. "So we rushed her to our San Francisco studios that night," Mendelson told The Washington Post. "She lost the tooth the next day, and you couldn't understand her at all."

Charlie Brown got a rock, and kids didn't like it

Peanuts was a semi-autobiographical enterprise, as creator Charles Schulz based unlucky sad sack Charlie Brown on himself as a child. Nevertheless, Schulz didn't have much sympathy for the character, and he rarely wavered from Charlie Brown's relentless losing streak in all endeavors. In It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown, for example, the character is a mess. He screws up his simple ghost costume (cutting out way too many eyeholes), and while Trick-or-Treating, he somehow receives multiple rocks while his friends receive candy and other sweet treats. Poor Charlie Brown can't win, even when others don't even know they're dealing with Charlie Brown.

"[Schulz] said that maybe we ought to have Charlie Brown get a rock," producer Lee Mendelson told The Washington Post. "I said, 'Oh come on, that's a little too harsh and cruel.' But the more I protested, the more he wanted it." And that's why Charlie Brown wound up getting three rocks in his Halloween treat bag. But Peanuts fans apparently aren't as mean as Peanuts' creator. After It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown first aired — and following subsequent airings over the next few Halloweens — Schulz's offices in California were bombarded with shipments of candy sent in by little kids, addressed to "Charlie Brown."

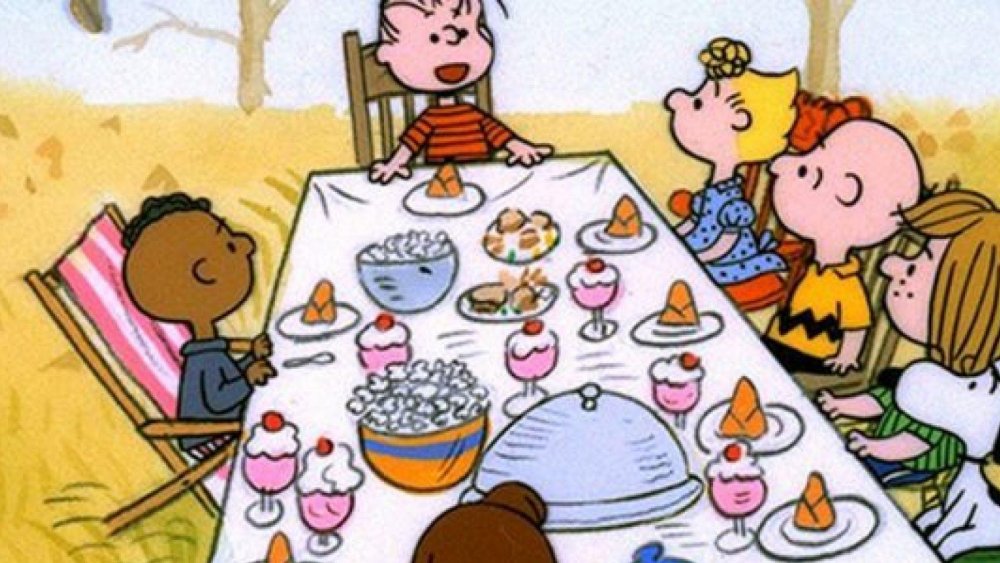

The Charlie Brown Thanksgiving controversy that wasn't

A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving aired in November 2018, as it had every year since 1973. But for the first time, or at least in large numbers, viewers noticed something potentially problematic in the otherwise innocuous special in which Charlie Brown hosts a bunch of kids in his backyard for a makeshift Thanksgiving meal. The group sits around a large rectangular table (actually a table tennis game surface) with Linus and Marcie at each end. Sally, Snoopy, Peppermint Patty, and Charlie Brown are sitting on one of the longer sides, and Franklin is all by his lonesome opposite them.

What's wrong with this picture? Franklin is the Peanuts universe's sole Black character, and it would seem that he's been segregated off by himself. Franklin's situation became a trending topic on social media the night of the broadcast, which fell just a few months after the 50th anniversary of Franklin's introduction to the Peanuts strip. It's likely just a coincidence that Franklin was seated alone, as Peanuts creator Charles Schulz fought to include the character back in 1968.

At the height of the Civil Rights Movement and following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Schulz integrated the previously all-white Peanuts with the addition of Franklin. The cartoonist even threatened to quit drawing the lucrative and popular Peanuts if distributor United Feature Syndicate didn't let him bring in the character. So while things might look odd in the special, it seems Schulz's intentions were pure.

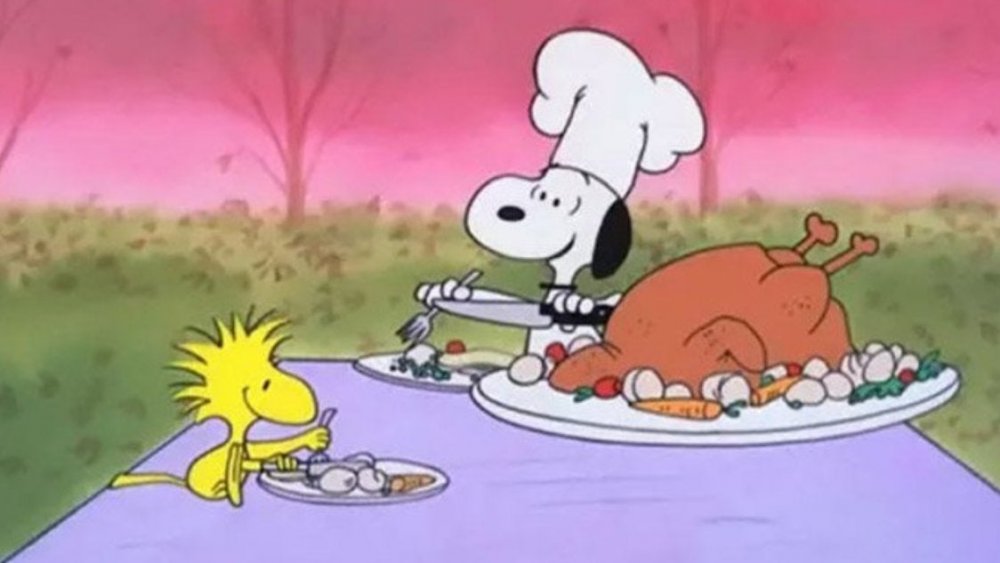

Is A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving a horror movie?

As the credits of 1973's A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving roll, plucky pooch Snoopy sits down to enjoy a roast turkey with his best friend, Woodstock. (After helping Charlie Brown cook a mediocre feast of popcorn and toast, he apparently made a real Thanksgiving dinner in his doghouse.) In a ghoulish note, Snoopy carves off a thick slice of turkey for his bird friend, which he happily devours. That, in a word, is cannibalism, right in the middle of this family-friendly TV special.

The scene was conceived, in complete innocence, by Peanuts creator Charles Schulz. "At the time it bothered me," producer Lee Mendelson told the Chicago Tribune. "And I said, 'I really don't think we should have the bird eating turkey.'" His reservations only made Schulz want to include the sequence more, and so it stayed in the show.

A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving initially ran 25 minutes, and a few years down the line, CBS asked Mendelson to cut three minutes to allow for more commercial time. His first choice for deletion? Woodstock eating bird meat. But when the rights to the Peanuts specials went to ABC, the network restored them to their original length, and Mendelson regrettably "had to put the scene back in."

Be My Valentine, Charlie Brown is far too real

It's been well-established that Charlie Brown is the cartoon version of creator Charles Schulz as an unhappy child. Other parts of the Peanuts world are based on real people, too, such as the object of Charlie Brown's undying affections, a young lady known as the "Little Red-Haired Girl." First mentioned in a Peanuts strip in 1961, her presence looms large in 1975's Be My Valentine, Charlie Brown. Charlie Brown convinces himself that his crush, who probably doesn't know he exists and who doesn't even appear on screen during the special, plans to send him a Valentine. But because this is a Peanuts special, she doesn't, and he gets sad.

This is all loosely based on a similar unresolved love situation experienced by Schulz. The Little Red-Haired Girl is based on Donna Johnson, with whom Schulz worked at Art Instruction, Inc. in Minneapolis in the early 1950s. According to Vanity Fair, they enjoyed a brief and sweet romance. Johnson, however, was torn between two lovers — Schulz and another man named Al Wold. And when Wold proposed, Johnson chose him over Schulz.

Less heartbreaking are some of the other inspirations for Be My Valentine, Charlie Brown. When Schroeder passes out Valentines to classmates and calls out their names, he mentions "Joanne Lansing." That's a shoutout to artist and ink/paint supervisor Joanne Lansing, who worked on dozens of Peanuts specials in the '70s, '80s, and '90s, including Be My Valentine, Charlie Brown.