The Ending Of A Beautiful Mind Explained

A Beautiful Mind dramatizes the real-life story of real-life genius John F. Nash, who is known for his pivotal work in game theory. The film, partially based on a biography of the same name, unfolds through Nash's lens of the world. However, halfway through, we realize Nash isn't a reliable narrator, and much of what we've taken as truth may not be factual.

For a viewer with no prior knowledge about Nash, A Beautiful Mind initially seems like a story about how one man's genius will save the United States from deadly Russian interference. But this is no triumphant Cold War tale. Instead, Nash's trials and tribulations represent the constant battle of a schizophrenic man learning to live with a brain that is his greatest asset, but also could be his worst enemy. In the end of the film, Nash wins a Nobel prize. His hallucinations remain present after the ceremony — as do his loving wife Alicia and their son, signaling his ability to live with schizophrenia. Nash endured a long road to the peace depicted in the film's final act. This is the ending of A Beautiful Mind explained.

John Nash is a special kind of genius

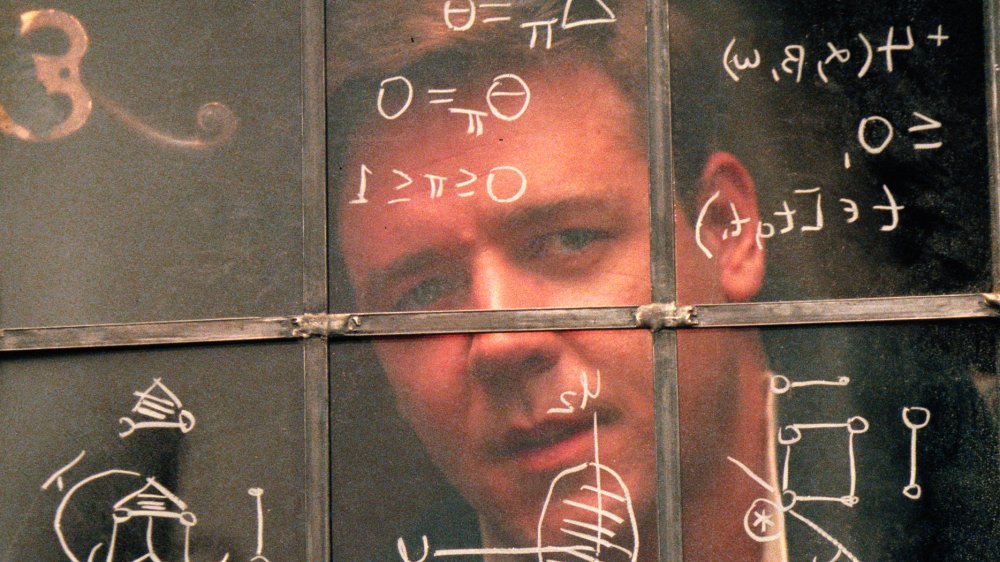

A Beautiful Mind begins with Nash's graduate studies at Princeton in 1947. A peer mentions he is one of two recipients of the Carnegie Scholarship, certifying Nash has an elevated level of smarts. Nash takes his genius a step further, however: When his roommate Charles arrives, he blabbers nonstop. It doesn't really bother Nash, as he is too occupied writing out equations on his window and in his notebook. Charles is able to finally break the ice by jumping up on Nash's desk and offering a drink from his flask.

Nash knows he's smart. He thinks he's too good for school, in fact. When his peer Sol wonders if he will ever show up to class, Nash is quick to respond: "Classes will dull your mind, destroy the potential for authentic creativity." All the while, Nash scribbles away in his notebook — apparently he's capable of extracting an algorithm by observing the movement of pigeons. Professors also question his truancy, but Nash assures them he intends to publish an original idea.

Nash develops important original work

The game theory breakthrough Nash makes, paving the way for the rest of his career, happens pretty quickly. And like so many great discoveries university students make in movies, the idea is sparked in a bar. Roommate Charles, the free-spirited English student that he is, convinces Nash to take a break and go to the bar — even though the last time they went, he approached a woman and was a bit too straightforward about taking her home. Nash is neck deep in work when his colleagues have him pause to take notice of a beautiful blonde that entered the bar. They rattle off "every man for himself" plans, but then Nash's mind starts to churn. What if no one goes for the blonde? The friends don't get in each other's way, and they don't insult the other girls. It's the only way for all of them to succeed.

Nash repeats, and ultimately refutes, a theory by economist Adam Smith, arguing that they must do what's best for themselves and the group. He runs out in excitement before putting his idea to use.

The theory fulfills Nash's publication requirement at Princeton and lands him an appointment at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

First comes class, then comes marriage

It's a little fishy when flirty vibes radiate off one of Nash's students at MIT. He is clearly taken by the way the student, Alicia, uses her charm and polite manner to ask nearby construction workers to find another task so Nash and his students can get through class with their windows open. However, this is only Alicia's first moment of standing up for Nash. In terribly hot weather, Nash is having an impossible time teaching with the windows open due to loud noise from the construction. She uses her privilege as a woman in a dominantly male space to ensure a better learning environment for her peers and professor. Furthermore, Alicia's presence alone is unusual. She is one of few women in the class, and given the story takes place in the early 1950s, she must have been a truly remarkable student to be at MIT.

When Nash and Alicia start dating, she really pulls him out of his antisocial shell, indicating her genuine intentions for their relationship. Romance sparks when the couple attend a high-end dinner and Nash paints constellations in the sky for Alicia. It's quite the picturesque moment for what feels like could be a great love story.

This is not a Cold War drama

Things take a turn for the dramatic when Nash is recruited by the U.S. Department of Defense by a man named William Parcher. After Nash cracks an encryption for the Pentagon, Parcher starts showing up with secret assignments for John to take down the Soviets. It's exciting to watch Nash's genius unravel top secret information to save the free world. Unfortunately, with that work comes enemies looking for that classified information. It seems as though Nash is being followed. One night he and Parcher set off on a car chase as they are pursued by Soviet agents with guns blazing.

As the audience later learns, this thrilling episode never happened. Nash flees mid-lecture while visiting Harvard, paranoid that the Soviets are after him, and it turns out everything is the result of his own delusions. He is sedated and put in a psychiatric facility for treatment under the eye of Dr. Rosen, who diagnoses Nash with paranoid schizophrenia. Has the whole movie been one big hallucination?

John's hallucinations build his character

It turns out the focus of Nash's work, which has always been the center of his life, is completely inaccurate. Nash accepts his diagnosis when Alicia brings him all the unopened confidential envelopes he had periodically dropped off at a stately mansion, explaining that the property was completely abandoned. At this moment, not only does Nash have to process a life-altering diagnosis, but he has to accept that the most exciting part of his life isn't real. Early on, we know Nash thinks he is too good for even the most intelligent of mathematical academia. He hardly takes mind of his peers while at Princeton. This is furthered by his boredom while working at MIT. Though a hallucination, Parcher brought real purpose to Nash's life. He felt like his work was really having an impact. Reality squashes that confidence — and Nash's vigor for life.

Sadly, his closest friend is also a hallucination. Charles was the key to loosening up Nash, even if only a little bit. He was the first to push Nash to be relatively social, and more importantly, he gave Nash the kind of comfort and human connection only a best friend can provide. The discovery that he is a figment of Nash's imagination is almost like suffering the death of an actual person.

Navigating mind tricks

Given Nash's strong bond with Charles and Parcher, it's understandable that it takes him some time to fully accept they were hallucinations. After he leaves the psychiatric hospital, things at home with Alicia and their new baby aren't great, especially because his medication has depressive side effects. Frustrated, he stops taking them — and like clockwork, Parcher pops up again. His explanation for abandoning Nash is so convincing that you might believe it if the movie wasn't based on a real story about a math wiz with schizophrenia. It's only when the drama swells once again that Nash has an epiphany. Up to this point, Alicia has been a caring and helpful partner. However, right after she discovers a shed full of Nash's schizophrenic-induced work, Alicia finds their baby on the verge of drowning. Nash believed Charles was watching him in the tub.

Finally convinced that Nash is a danger to both of their lives, Alicia dashes to the car to make a getaway. But Nash comes to a realization of his own, allowing him to take the first step in learning to live with schizophrenia. As he tells a terrified Alicia, he now understands that Marcee — Charles' niece — can't be real because she never ages. Despite the returned hallucinations, Nash doesn't go back on his medication... but Alicia stays by his side.

Alicia's love for John is genuine

Clearly, John Nash's story could have gone completely awry had it not been for Alicia. Their marriage is a watershed moment for him and helps ground him as he learns to live with schizophrenia. In fact, Alicia's support is one of the movie's points supported by real-life scientists in its portrayal of the psychiatric disorder. They are a true partnership, as Alicia trusts Nash, even after all the lows, through his decision not to take his medication. She understands his mind is capable of greatness, even beyond math. Alicia's constant support, even when she fears for her own and her child's lives, is made more effective through Nash staying in a familiar environment, Princeton University, during his recovery.

Psychiatry professor Dr. Steve Lamberti told ABC News that a structured, predictable and supportive environment makes all the difference for many individuals with schizophrenia. In particular, family support has increasingly become part of family education and treatment. The real-life Nash explained to a colleague in an email that his condition eventually improved: "I emerged from irrational thinking, ultimately, without medicine other than the natural hormonal changes of aging."

Psychiatric treatment in the 1950s

Given all the pharmaceutical commercials television viewers have to endure in the present, it comes as no surprise why someone would resist taking antipsychotic medications, especially at a time when treatment for mental illness was fairly new. Discourse around drugs was very different. Nash is irritated that the pills he's given dull his mind and diminish his sex drive. More scarring is the insulin shock therapy (this method has fallen out of favor, though safer shock therapy is still used). When Nash is first committed, Alicia can hardly watch as the hospital staff puts Nash into an insulin-induced coma. A nurse administers the insulin with a large needle and Nash stares up to Alicia through a window, eyes begging. As he starts to drift off, a tear rolls down.

Dr. Rosen's mode of committing Nash to the hospital also must have been traumatizing. He had a breakdown in front of important colleagues on the campus of a world-renowned institution. Like a wild animal, he was held down by numerous men and then sedated.

Martin Hansen: Enemy turned comrade

Martin Hansen, perhaps only second to Alicia, is key to Nash's stability. As the other recipient of the Carnegie Scholarship at Princeton, Hansen starts out as Nash's foe. Their class rivalry evolves, becoming frenemies and then friends. One could even argue that Hansen pushing Nash's buttons leads Nash to work harder at Princeton (though Nash would probably never admit this). Hansen taunts Nash, but as they become two respectable men of mathematics, they come to more than just tolerate one another.

Hansen, who later becomes the mathematics department head at Princeton, allows Nash to work in the library and audit courses. This is lifesaving. The stability from a regular schedule and stimulating his mind allows him to steady his schizophrenia. Nash falls into a rehabilitating routine and eventually is allowed to teach again. Hansen seems nervous at first, as he's witnessed Nash interacting with his hallucinations. But he's understanding, allowing Nash to prosper — and ultimately win a Nobel prize.

The oversimplification of John Nash

Directed by Ron Howard, A Beautiful Mind is based on the biography of the same name by Sylvia Nasar. Like any Hollywood adaptation, some changes have been made to actual events. His real life is substantially more complex: As outlined by Slate, Nash and Alicia had a bumpy marriage. She filed for divorce after five years, but by 1970, Nash moved back in with Alicia. It wasn't until he won the Nobel in 1994 that they really rekindled their relationship, remarrying in 2001.

Before his marriage, Nash fathered a son to Eleanor Stier out of wedlock. He wanted no involvement and Stier had to take legal action to get Nash to pay child support. At one point, Nash and his first son were estranged for 17 years. (Both of his sons were named John.)

The film also omitted Nash's possible homosexuality. Nasar described his "first experience of mutual attraction" as being with a man and said that his first loves were one-sided infatuations with other men. Such unrequited feelings happened more than once. While working at the RAND Corporation and as an undergraduate student, he made sexual passes at colleagues; one friend said Nash once kissed him and tried "fiddling around with" him while driving. In 1954, Nash lost his job at RAND after being arrested for indecent exposure in a Santa Monica bathroom. Still, Nasar described the movie as "true to the spirit of Nash's story."

The final moment of the movie is John's full acceptance of himself: husband and mathematician with schizophrenia

The culmination of Nash overcoming the perils of schizophrenia and establishing himself as a respected academic manifests in the award of his Nobel Prize. Nash's speech converges his identities as a mathematician and schizophrenic: "After a lifetime of such pursuits, I ask, 'what truly is logic?'" Even more touching is the moment he dedicates the award to Alicia. Looking at his wife among a sea of people, he tells her, "It is only in the mysterious equations of love that any logical reasons can be found. I'm only here tonight because of you... you are all my reasons." It's a kind tribute and honors the importance of having a stable companion while navigating a mental disorder.

By acknowledging schizophrenia as part of Nash's most victorious moments, we understand his success comes from not ignoring a significant though potentially destructive part of himself, but by coexisting with it. Nash's genius was possible not because of a singular piece of his mind, but rather the entire brain working as a whole.