The Untold Truth Of The Rocketeer

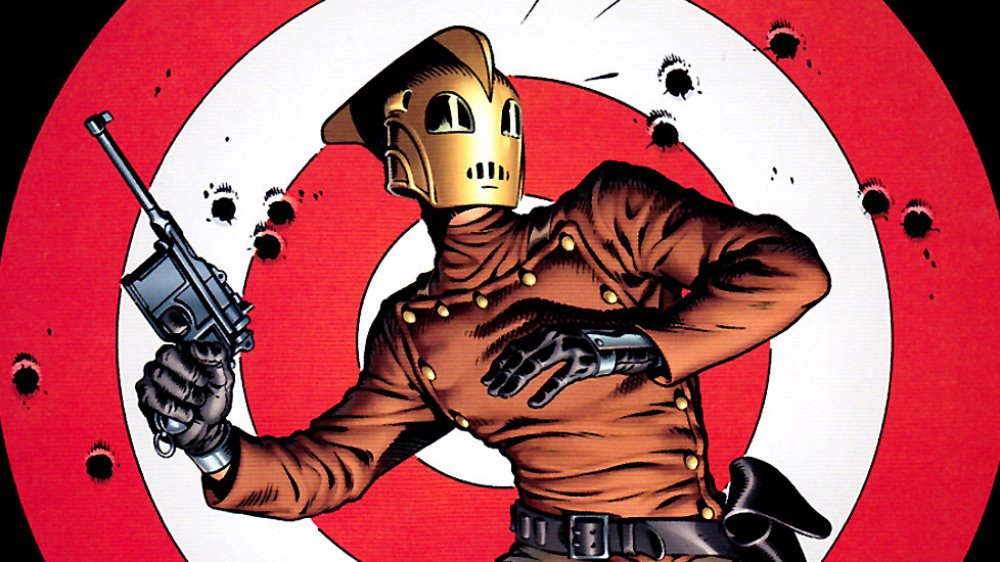

Years before the Marvel Cinematic Universe was the biggest thing in pop culture history, Disney blasted into theaters riding the jetpack of another hero with The Rocketeer. While it didn't break any box office records, the stylish retro adventure that hearkened back to the Golden Age adventures of Flash Gordon, Doc Savage, and The Shadow became a cult favorite, and it's found itself on more than one list of underrated superhero movies, with very good reason.

The Rocketeer's history doesn't begin on film, though. Like most superheroes, Cliff Secord got his start on the comic book page, courtesy of creator Dave Stevens, but you won't find him digging through back issues published by Marvel or DC. From its beginnings as one of the first great independent comics to ever find mass media success to the all-too-short legacy that Stevens left behind with his pulpy masterpiece, here's the untold story behind The Rocketeer.

Meet Dave Stevens, the man behind The Rocketeer

The Rocketeer stands even today as a masterpiece, but one of the things that makes it so impressive is that when it debuted in 1982, making comics wasn't even Dave Stevens' full-time job. He'd gotten his start in his artistic career in the mid-'70s working with the legendary Russ Manning. At the time, Manning was working primarily in comic strips, and Stevens assisted him by inking both the Tarzan and Star Wars strips.

By the late '70s, though, Stevens had moved to illustration jobs in very different media. After starting out as a storyboard artist for Hanna-Barbera — including working on Super Friends, sadly the closest we ever got to seeing him work on Batman or Superman — Stevens wound up doing work for films like Raiders of the Lost Ark. Clearly, he was a pretty good fit for a project that was inspired by the pulpy adventure serials of the '30s and '40s, and since Radiers launched the Indiana Jones franchise in 1981, it's likely that he was working on the first few installments of The Rocketeer at the same time. That's especially staggering considering that the art he was creating for The Rocketeer was incredibly lavish even by today's standards, let alone when compared to the other comics coming out during that first big indie comics boom of the '80s.

Incidentally, after his death in 1981, Russ Manning was so well regarded that the comics industry's award for "Most Promising Newcomer," awarded yearly at San Diego's Comic-Con International, was named for him. Its first winner in 1982? Dave Stevens, for his work on The Rocketeer.

The Rocketeer blasts off

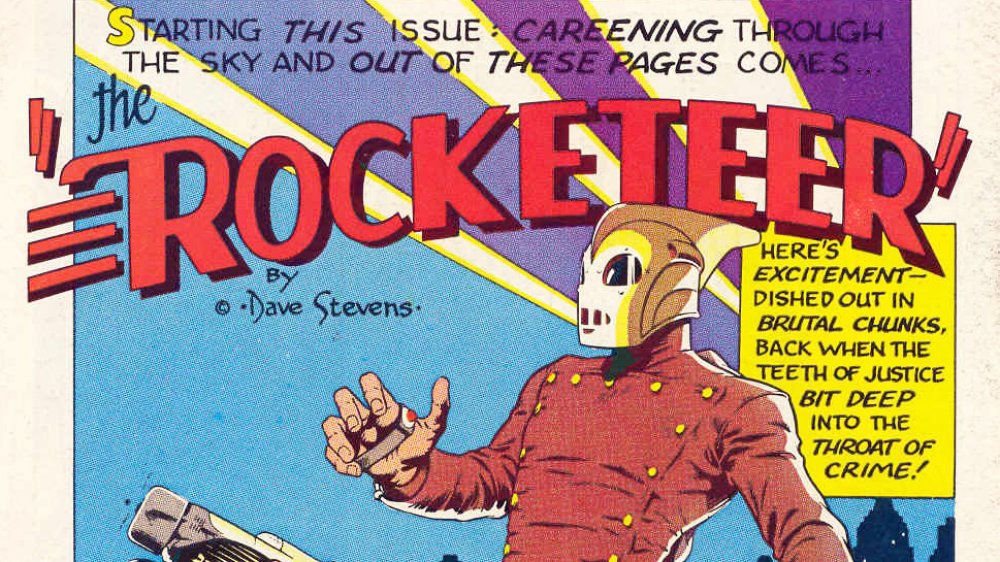

As one of the most notable independent comics of its era, it might be surprising that The Rocketeer's debut didn't exactly come with a whole lot of fanfare. In fact, it didn't even make the cover.

Instead, the first installment of The Rocketeer came as a backup story in Pacific Comics' Starslayer #2. Starslayer was an interesting but obscure sci-fi comic written and drawn by Mike Grell, best known for his work on Legion of Super-Heroes and Green Arrow at DC. The first Rocketeer story was only six pages, and it was announced on the back cover of Starslayer with an amazing blurb about how it featured "excitement — dished out in brutal chunks back when the teeth of justice bit deep into the throat of crime!"

That shouldn't be seen as a slight to Stevens or his art, though. For one thing, Stevens was still a newcomer to his own stories, while Grell was an established and popular creator. Putting Rocketeer in his comic, as odd as it may seem today, was probably the best chance of getting stores to carry it and fans to read it. Also, on a purely functional level, those six pages might've been all there were of The Rocketeer back in April of '82.

Not only was Stevens doing The Rocketeer on the side as a passion project, he also wasn't known as the fastest artist to ever put pencil to paper. As comics creator Mark Evanier would put it in his obituary for Stevens, "It wasn't so much that he was slow, as his friends joked, but that he was almost obsessively meticulous." His art — which he penciled, inked, and possibly colored himself in addition to writing the story — was incredibly detailed, and that took time. In fact, The Rocketeer is notable not just for its quality, but by how much it does with a relatively small amount of space. The entire story, start to finish, is only 120 pages published over the span of 14 years, which works out to about eight and a half pages per year. When they're as good as what Stevens is doing here, though, that's really all you need to cement your legacy among the greats.

Cliff Secord's origin story

When you get right down to it, the story of The Rocketeer is one of those classic structures that you learned about in high school English class. You know, man vs. man, man vs. nature, man vs. self, man with pin-up girl love interest and jetpack vs. Nazi circus performers. Sure, it's a story we've all seen before, but it's what you do with it that matters, right?

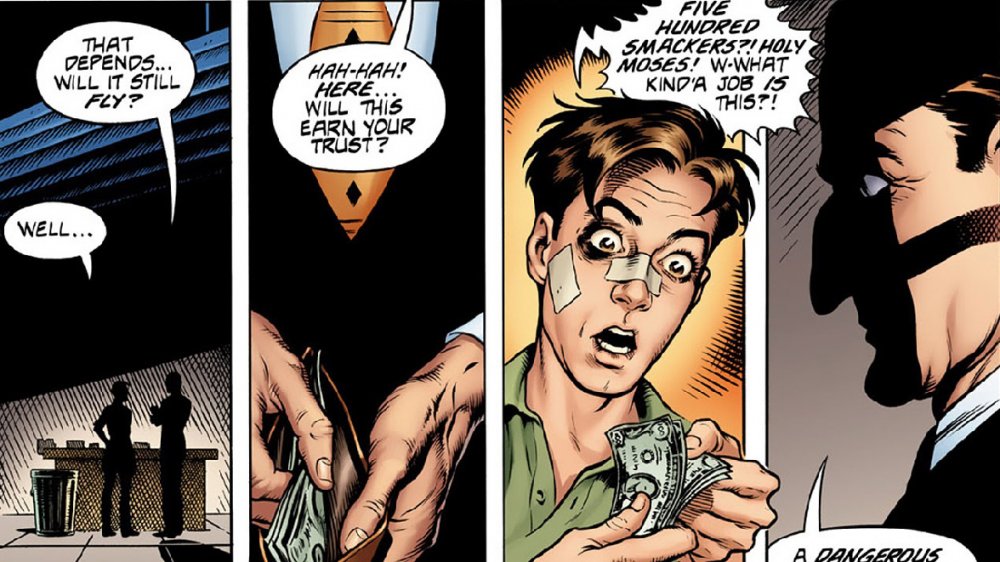

The story begins in April 1938 — which, probably not coincidentally, is the same month that another famous flying character that you might've heard of first appeared in Action Comics #1 — when a prototype jetpack is stolen by a pair of crooks who hide it in the cockpit of a stunt plane while they're trying to avoid the police. The jetpack is found by stunt pilot Cliff Secord, who quickly gets caught up in a web of G-men trying to recover the rocket and German spies who want to take it to Hitler to create an army of flying Nazis.

Cliff's initial plan, much like Peter Parker's back in the day, is to use the rocket to make money to impress his girlfriend, Betty — who, for her part, keeps insisting that she doesn't care about Cliff's wealth (or lack thereof) and tries to get him to stop being a jerk about it. In the end, though, he winds up using it to stop the Fifth Columnists and to bring down a hulking bad guy from his old circus days. It's pretty simple, old-school action, but it's done really well. Cliff could easily come off as a huge jerk, but Stevens makes it clear that his hot temper and possessiveness are due to his own insecurities, and he manages to fit right in with the classic pulp hero who loses more fights than he wins but still gets back up. That makes it accessible to new readers, but there's still plenty there for fans who might've been around a while, too.

Drawing inspiration from pulp fiction

The Rocketeer is a comic (and a film) that's pretty obvious about its inspirations, and one of the more entertaining ways that manifests itself throughout its run is the way that Stevens ties his character to the legacy of the pulp heroes that inspired him. We've already talked about the significance of the April 1938 origin for the Rocketeer, but there are a few big ones that have way more prominence in the comic themselves.

It's done in a pretty subtle way — well, subtle by the standards of a comic where a guy with a golden helmet flies around with a purple jetpack, anyway. The characters in question are never actually named, which has as much to do with skirting around the copyrights on those characters through plausible deniability as it does with the fun of realizing what's really going on. If you know what Stevens is referencing, though, they're pretty easy to spot.

The biggest reference comes near the end of the first arc, when it's revealed that the rocket — officially named the Cirrus X-3 — was created by a character who bears a striking resemblance to iconic pulp hero Doc Savage. Unfortunately for the lawyers over at Conde Nast, Doc is never named and in the few panels he actually appears, he's wearing a flight suit that obscures his trademark look. The bigger clue than Doc himself comes when Cliff encounters two of his sidekicks known as the "Fabulous Five," who are pretty clearly "inspired by" Monk Mayfair and Ham Brooks.

The second arc, "Cliff's New York Adventure," brings in an equally famous pulp hero. While he's identified in the story as "Jonas" — a reference to the headquarters in the B. Jonas Building that he used in his earliest adventures — the wealthy New Yorker who hires Cliff for a job is definitely meant to be the Shadow, the direct vigilante ancestor of Batman. That adventure also includes a flashback to Cliff working at a circus with an extended reference to Tod Browning's classic film Freaks.

Betty vs. Bettie

If you've ever seen Dave Stevens' artwork, the first thing you're likely to notice — long before you get around to the compelling facial expressions, fluid lines, and dynamic layouts that were years ahead of their time — is that he really, really likes to draw classic-style pin-up girls. Specifically one pin-up girl — Bettie Page.

To say that the real-life Bettie (with an "i" and an "e") was the inspiration for The Rocketeer's Betty (with a "y") is putting things about as mildly as a saltine dipped in ketchup. Page is often referred to as being Stevens' "muse," and in fact, while the one-time "Queen of the Pin-Ups" had fallen into obscurity, there was a wave of new interest in her that began in the '80s and elevated her to an enduring pop culture icon whose jet-black bangs are still being sported by fans today. It's no exaggeration to say that Stevens was largely responsible for that renewed fandom, both through The Rocketeer and through more direct illustrations of her.

Stevens would end up contacting Page upon discovering that she was still alive in Los Angeles, completely unaware of her own retro fame, and he sent her a check to compensate her for using her likeness for The Rocketeer before meeting her in person. When asked in an interview with Comic Book Artist whether Page had been aware of her likeness being used before he got in contact with her, Stevens answered, "No, totally unaware. You know, she was in her 70s, and most women her age don't buy comic books!" Page and Stevens would go on to become friends, and according to artist Mark Evanier, he even helped Page out with her errands. As Evanier told it, "One time, he told me — and without the slightest hint of resentment — 'It's amazing. After years of fantasizing about this woman, I'm now driving her to cash her Social Security checks.'"

Why Disney decided to make The Rocketeer

If you're old enough to remember the summer of 1989, then you already know that Tim Burton's game-changing Batman movie was one of the biggest things to hit theaters in that entire decade. It dominated not just the movies but the entirety of pop culture, with the yellow and black logo that was downright inescapable. Naturally, after seeing the success of Batman, other studios tried to get in on the action, although they did so in some pretty weird ways. Rather than just producing their own stylish takes on popular superheroes, studios seemed to think that people were just really into Batman's retro '40s aesthetics, leading to big-screen versions of franchises that didn't really resonate with current audiences, like The Phantom, The Shadow, and Dick Tracy.

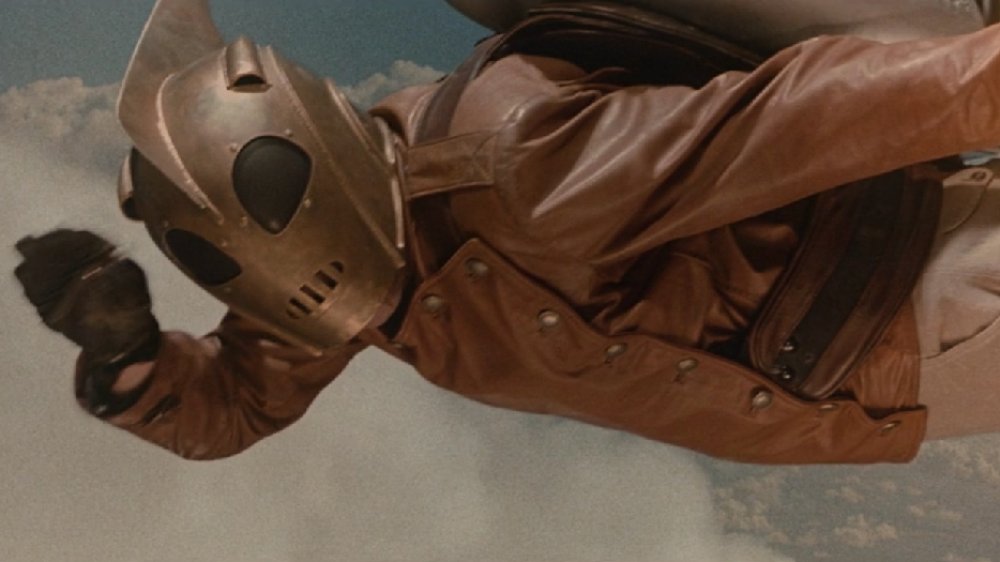

While Disney would eventually just corner the superhero market by buying Marvel Comics and its billion-dollar cinematic universe, The Rocketeer probably seemed like the best of both worlds for the Mouse House in the post-Batman landscape. It was a critically acclaimed modern superhero comic that already had the retro look and feel, with a straightforward, easily adaptable story that would lend itself well to a cinematic adventure. Done right, the 1991 film adaptation could've been Disney's answer to both Batman and Indiana Jones — something that it was frequently compared to in reviews.

As for whether they actually did it right, opinions vary. The movie does capture the look and feel of the comic pretty well, but despite having a great cast and some pretty thrilling sequences — and keeping Cliff as the same likable but bumbling good guy that he is in the comics — it does seem a little toned down. Also, there's one crucial flaw for the superhero movie audience of 1991. It wasn't Batman.

What got lost in translation

Obviously, the story of The Rocketeer underwent some pretty significant changes in the move to the big screen. For one thing, since copyright issues are a slightly more pressing concern for a movie made by Disney, the references to Doc Savage and the Shadow were removed, with the rocket in the film being a prototype made by real-life aviator/weirdo Howard Hughes. Along the same lines, Cliff's girlfriend, played by Jennifer Connelly, was renamed "Jenny," and lacked any elements of Bettie Page's signature look. We did, however, get former James Bond Timothy Dalton playing an Errol Flynn-esque villain in one of his most delightful, scenery-chewing roles.

Unfortunately, the film didn't do that well. Despite decent reviews — including Stevens saying that he was "satisfied with 70% of the film," a higher percentage than a lot of creators who've seen their work adapted — audiences didn't flock to the theaters for it. The movie barely made back its budget with its domestic release, and the Rocketeer only had one cinematic flight. In the years since, however, it's become a cult classic for superhero fans, and it even has a lasting legacy of sorts in today's superhero films. When the MCU was looking for someone to direct their own retro '40s superhero movie, Captain America: The First Avenger, they got The Rocketeer's Joe Johnston.

The Rocketeer after Dave Stevens

Sadly, Dave Stevens died in 2008 of leukemia at the young age of 52. The illness lasted years and profoundly affected Stevens' work after he finished the second major Rocketeer story, which would lead him to joke that it might've been a good thing that he'd always had a reputation for being slow to finish his art. He also had a reputation for being one of the nicest people in comics, and you'd be hard pressed to find anyone contradicting that.

While the 120 pages of The Rocketeer tell a complete story, they also establish a world where Cliff, Betty, and their pals could have endless adventures. To that end, IDW Publishing launched new Rocketeer comics in 2011, starting with an anthology series where other artists would do new short stories and then move on to longer miniseries. Perhaps ironically, it wouldn't take long before there were more Rocketeer comics that weren't drawn by Stevens than ones that were, but the creators did a solid job of keeping in line with the legacy that he'd left behind.

They even included the references to other '30s and '40s pop culture. The Rocketeer: Cargo of Doom featured Cliff encountering a certain giant, skyscraper-climbing gorilla imported from Skull Island, while The Rocketeer: Hollywood Horror featured not only a tentacled eldritch horror in the vein of Cthulhu but also a pair of detectives who'll be familiar to fans of The Thin Man''s Nick and Nora Charles. Also a story by the late Darwyn Cooke, another best-of-their-generation comics artist who died from cancer at the age of 53 in 2016, featured Betty using the rocket pack while wearing Cliff's signature leather jacket and very little else, and it's hard to imagine that Stevens wouldn't have approved of that.