The Strangest Thing Mary Padian From Storage Wars Ever Found

Mary Padian, who went by the reality-TV-bestowed title of "The Junkster" on Storage Wars, has lifelong experience in secondhand treasure hunting — and, as you might expect, she's seen just about everything. Growing up with her father in the car repair business meant he kept a junkyard full of secondhand parts, which is where Mary's interest in the trade was born. As an adult, her Texas-run business flipping secondhand finds got her noticed for the short-lived Storage Wars: Texas — and her bubbly nature let her keep her TV job on the OG version of Storage Wars when the spin-off fell apart.

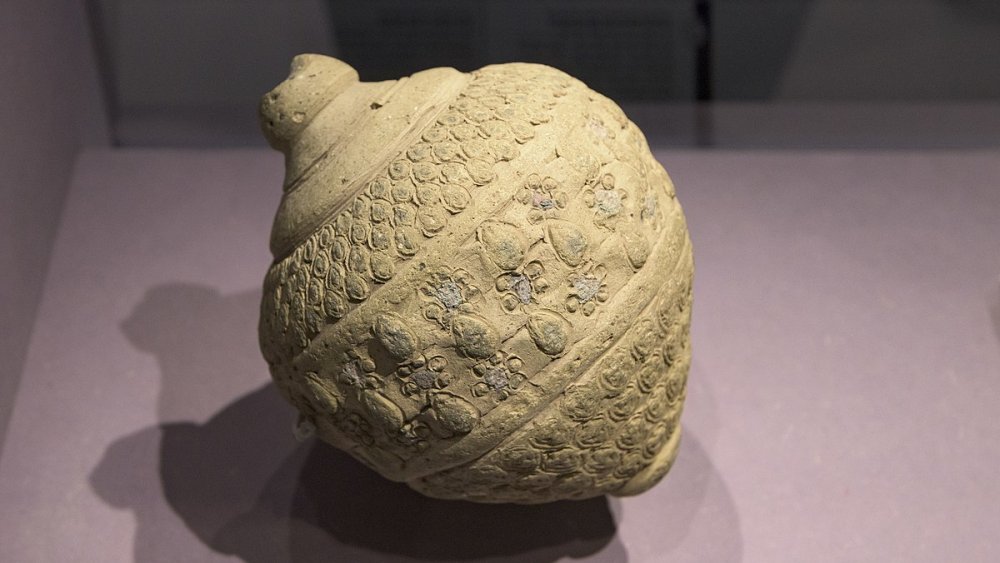

Back in 2017, Padian gave an interview with SpareFoot, and she was asked what the weirdest thing she had ever come across in her time spelunking for refurbishable treasures. Her answer was indeed bizarre — both for its extreme age, and for how far it would have needed to travel to be turned up in America: a Byzantine Empire ceramic grenade.

"I found out that when they would throw the grenade it would break and cause a fire," Padian explained to SpareFoot. "You couldn't put out the fire with water. Nothing would make the fire go out, and so to this day they still haven't been able to replicate whatever the substance is they used inside there."

An ancient and mysterious weapon

The grenade is a relic of the Byzantine Empire that existed between the fourth and 15th centuries, with its capital at Constantinople as the center of the middle-ages Christian world. The contents of the grenades themselves — often referred to as "Greek fire" — was believed to have been invented around the seventh century, and as Padian mentioned in her interview with SpareFoot, to this day, no one is sure how the concoction was manufactured. A good modern analogy for it would be napalm — however, Greek fire was a liquid base and projected using a pressurized system, rather than jellified like modern napalm. The Byzantine Empire used it to astounding effect in naval battles with a ship-mounted, flamethrower-like tool, as well as employing it in thrown ceramic grenades that would shatter and ignite on impact.

The recipe was a closely-guarded state secret — almost all description of Greek fire comes from secondhand sources that only knew a few of the required ingredients. We know today that it likely used crude petroleum and resins, but modern attempts to recreate it can't produce the antiquity described effects of instant ignition with or without water, nor can it produce the same level of damaging capability. Even soldiers trained to use the liquid and the machines used to propel it only knew how to operate modular portions of the system, so no one person knew how the entire machine worked, much less how to manufacture its ammunition. Greek fire is truly a chemistry miracle of its age — and the secrecy so effectively kept, that time's erosion and the collapse of the Byzantine Empire to the Ottomans means it has been lost.

What a journey this little grenade must have seen — to have been manufactured over a thousand years ago, before Europe even knew of the New World, and end up in the hands of a modern reality TV star.

Mary Padian has made some other strange discoveries

Padian has stumbled upon plenty of other strange finds in her days hunting for surprising treasures amid presumed trash. In her discussion with SpareFoot, Padian mentioned that what has awaited her on the other side of the storage locker doors has occasionally been both eye-catchingly unique and totally shocking — like 18th-century camel saddles and a woman's collection of urns.

"The stuff we've found in storage lockers is crazy," Padian said. "It's crazy what people keep and what's important to them. That's the most interesting thing to me. Like this one lady had a shelf that she had built and it had all these urns of all her pets, and her ex-husbands."

As odd as a lined-up row of urns is, it's difficult to top the Byzantine grenade, however, simply because of its age and its fascinating, incomplete history.