Movies We Want To See In DC's Dark Universe

Joaquin Phoenix's take on the Clown Prince of Crime in Todd Phillips' Joker isn't just memorable, but historic — how often does a comics-derived movie get to stand on its own, heedless of continuity, tie-ins, and sequels? Joker is unlike any other comic book movie ever made, and it might just change the genre forever.

Where, then, can DC go from Joker? With decades of history at its disposal, the studio has a vast variety of stories to choose from that could truly dazzle when freed from the main DCEU timeline. From its legendary library of Elseworlds comics, an imprint specifically created to house unique interpretations of its iconic characters, to its most celebrated runs, the choices are very nearly endless. We're here to break down which arcs, storylines, and graphic novels we'd most like to see become part of the DC initiative that rumors are hinting might be a "Dark" or "Black Universe" of standalone movies. Leave all your notions of continuity at the door.

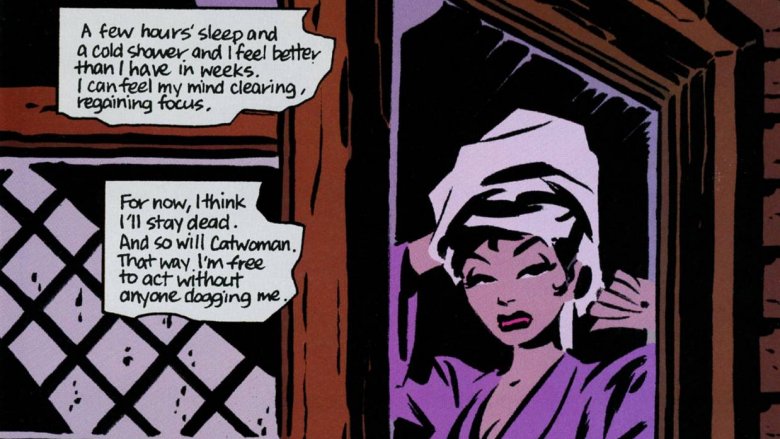

Catwoman

Catwoman has worn many hats (albeit all with pointed ears) in the DC universe. She's been a jewel thief unmotivated by anything but her own desire for decadence. She's been Batman's lover, occasionally his fiancee, and in a few realities, even his wife. She's been part of villainous team-ups for as long as her independent nature allows. And occasionally, she's been a hero — on her own terms and with very different tactics than those of, say, the Justice League, but a hero nonetheless.

Her 2001 solo series, written by Ed Brubaker and visually masterminded by Darwyn Cooke, exemplified this and could form the basis of an incredible cinematic outing. In it, Selina returns to the slums of Gotham's East End where she was a prostitute, ersatz big sister to the women she worked alongside, and eventually a burglar. Upon learning of a serial killer preying upon the unprotected women of the neighborhood, she decides to hunt down the murderer herself — and in so doing, fight for the downtrodden the city elite ignore.

It's a brooding masterpiece of a series, one that could easily make the jump to the silver screen as a smoldering neo-noir tale of the streets. Cooke's stylish, midcentury take on Selina and her world provides a timeless aesthetic that wouldn't just impress, but look unlike any other superhero story committed to film. Catwoman wouldn't just be an interesting experiment — it would be a dazzling new vision of the genre's capabilities.

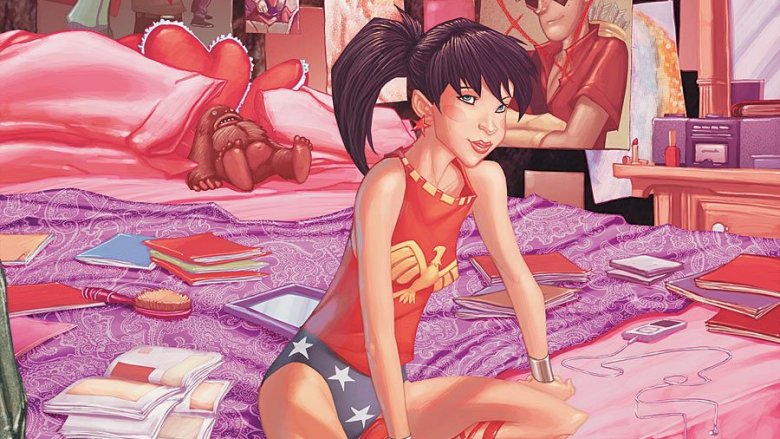

Teen Titans: Year One

From the 2003 animated Teen Titans series to the deliriously delightful Teen Titans Go!, audiences can't get enough of Robin and whatever motley crew of sidekicks he's assembled to take on the world. Though most of these incarnations draw inspiration chiefly from the 1980s New Teen Titans series, there's likely enough life in the idea of adolescent adventuring to dig deeper into the team's past — specifically, to its original 1966 lineup of Robin, Kid Flash, Aqualad, Speedy, and Wonder Girl.

While the original run has an era-specific charm all its own, Amy Wolfram and Karl Kerschl's Teen Titans: Year One provides a modern vision of the team that practically begs to be adapted to film. Chafing beneath the demands of the adults in their lives that refuse to see them as anything but children needing strong hands and stern words, the merry band of junior heroes strikes out on their own. Unsurprisingly, they're not entirely prepared to confront the villainy they find. But the fledgling group doesn't dissolve at this first blush of conflict: They rally, fight back, and form the team that would go on to make such a mark on the DC universe. Teen Titans: Year One wouldn't just be a light-hearted cape-and-cowl romp, but a genuine ode to the trials of the teen years — think a John Hughes flick, only with magical lassos and the ability to talk to fish.

The Outsiders

The first Suicide Squad movie has had an undeniably cultural impact — Harley Quinn's Daddy's Li'l Monster shirt will forever be in stock at a Halloween costume retailer near you — but its critical reception was lacking. There was much to love but much to loathe, only one truth emerging: The idea of a super-team with muddied morals is a potent one.

Consider, then, a movie centered around another team of DC characters who don't always play by rigid rules of good and evil: the Outsiders. Often tethered to more mainstream heroes by affiliation with Batman, the Outsiders are nevertheless a collection of misfits, oddballs, and heroes who have had more than a few falls from grace, yet they strive to do good in spite of this and succeed through their unique gifts and life experiences. Well-known characters like Nightwing, Starfire, or Arsenal could anchor audiences to stories they've already enjoyed, allowing the film to introduce unique heroes like Looker, a bank teller turned do-gooder vampire, and Indigo, a broken android from the far future designed for a villainy she rejects. Room for creative liberties is ample — the right team has decades of visuals, lineups, and plots to play with, from straightforward heroics to insidious blackmail schemes. The Outsiders could be interpreted as strike team, off-the-books enforcers, ragtag band of wannabes, and more. All it takes is the right bunch of filmmakers to make this story sing.

Batgirl of Burnside

Barbara Gordon has been stylish from the very beginning. Recall the ruffled motorcycle she rode in 1966's Batman, her early pioneering of the library chic look, and the wide and fabulous array of costumes in her closet. This attention to aesthetics informed one of the most recent iterations of the girl in the pointy-eared cowl: the "Batgirl of Burnside," whose cutting-edge adventures were chronicled in her 2015 solo series.

In this ode to life's early 20s and all the mishaps and magic they tend to incur, Barbara moves to Burnside, Gotham's hippest neighborhood, pulls on a new costume, and takes on a panoply of punchy new adversaries. Babs Tarr's neon-limned vision of a Gotham terrorized by influencers gone insane, mob-connected cosplayers, and rogue viruses born from the bowels of social media would fit right in alongside daring new visual approaches to the superhero genre like Thor: Ragnarok and Suicide Squad and indie outings like The Neon Demon. Barbara's world leans into the fantasy of superheroes, utterly uninterested in toning down what makes these stories unique. There's no body armor or drab Kevlar in this Batgirl's neck of the woods — instead, you'll find Doc Martens, bedazzled utility belts and bad guys who look more like Takashi Murakami sculptures than military operatives. A movie sprung from this vision wouldn't just delight but outright dazzle, establishing Batgirl as her own hero with her own challenges, mission, and neighborhood.

Superman: Secret Identity

Once upon a time, a boy named Clark Kent grew up in rural Kansas. But this Clark Kent wasn't raised in the superpower-rich environs of the DC universe — he lived in our world, where being named after Superman was a conscious joke on the part of his parents. Young Clark bore the name ably but inwardly sighed, resigning himself to a life of ribbing and Superman-branded birthday gifts. Then he started to float.

A metafictional tale of heroism, Superman: Secret Identity examines just what superheroes mean in our pop culture-laden world. In many ways, a movie adaptation of the stirring story would serve as a sort of lighthearted rejoinder to Joker — Clark embraces his powers, both in the literal sense of his flight and super strength, but also in the figurative, knowing what it means to make Superman real. Rather than taking on the mantle of the clown to mock a society gone mad, he dons a cape and shows the world that the line dividing impossible visions of goodness and reality is quite a bit thinner than anyone anticipated. Superman: Secret Identity is a joyous invocation of the superhero in everyone, a celebration of the spirit that led Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster to come up with the big blue Boy Scout in the first place. This is a Superman that wouldn't just take up the screen with his feats of goodwill — he'd fill the audience's hearts as well.

Wonder Woman: Amazonia

Wonder Woman's cinematic solo outing was a roaring success, and there's likely room for more than one interpretation of her astonishing adventures. After all, Batman and Superman have had more than their share of screen time according to a vast array of directors, writers, and actors — why not the third part of their trinity?

Wonder Woman: Amazonia, a 1997 Elseworlds story, is ripe for adaptation. Set in a turn-of-the-century London where Jack the Ripper murdered his way into becoming the king, the story finds Diana battling an entrenched patriarchy on the Victorian stage and the halls of power alike. Its strong visuals would make a unique splash: This Wonder Woman sports a Gibson Girl hairstyle and protects the crowded streets of Whitechapel. In many ways, this Wonder Woman story would have more in common with Sweeney Todd than Justice League — but that would be the movie's greatest strength. Much as Wonder Woman succeeded in placing its heroine within the maelstrom of World War I, so could this film highlight its heroine's unique strength by rooting it in a particularly dire chapter of English history. In the end, when Wonder Woman triumphs against the forces of violent, systemic bigotry, her victory would be all the sweeter for its unlikeliness.

Mister Miracle

Ah, to be a superhero. The powers, the costume, the... endless diaper changing? For Mister Miracle, juggling an inter-dimensional war, a recent suicide attempt, and a newborn son coveted by the most evil man in the universe are all part of the job. Tom King and Mitch Gerads' meditative take on the New Gods character juxtaposed his fantastic origins against the mundanities of life on earth. But this wasn't simply an exercise in contrast. King and Gerads used the superheroic whimsy of the DC universe to find feats of titanic heroism in the everyday, and the quotidian in an interstellar clash of good and evil.

Picture it: Literal gods crowded around a condo's coffee table, cooing over a baby who doesn't know the meaning of "the anti-life equation." Legendary villainess Granny Goodness offering her prodigal children Jell-O on the battlefield. Mitch Gerads' lurid colors would translate seamlessly to the celluloid fever dream Mister Miracle could become, given the right team. Superheroes represent our culture's highest ideals — why not smash them against our ordinary lives? Much like Superman: Secret Identity, a Mister Miracle movie could probe the boundary between our world and the ones we create, but with the high-octane power of Jack Kirby's legendary Fourth World stories and a tale that opens with a penetrating question: can Mister Miracle, iconic escape artist, escape his own mortality? The answer wouldn't just surprise audiences — it would enthrall them.

Animal Man

Meta humor has taken over pop culture. As a third Deadpool movie gathers steam, a similarly toned Harley Quinn cartoon debuts, and characters like Gwenpool fill the panels of their comics with ribs at the reader, an interesting absence asserts itself: Where are the metafictional superheroes who are taken seriously?

Enter Animal Man. A do-gooder with the ability to channel the powers of the animal kingdom, he is a family man with an interest in becoming famous, a vegetarian ethos, and a lackadaisical approach to protecting his secret identity. Already an intriguing character, he became all the more unique when, in 1990's Animal Man #19, the hero confronted his own fictional nature. On a peyote trip, he encountered another incarnation of himself who railed against being used as a puppet for others' entertainment, became confused, turned around... and stared straight at the reader, exclaiming, "I CAN SEE YOU!" He was joined in this terrible knowledge by Psycho-Pirate, the Golden Age villain who, we learn, was the only DC inhabitant who remembered the universe as it existed before the "Crisis on Infinite Earths" event. Eventually, Animal Man confronted writer Grant Morrison himself, demanding his slaughtered family back. Morrison's rejoinder was bleak: He needed to create drama, and anyway, a new writer would soon be taking over the book. Animal Man wouldn't just shake up the metafictional superhero formula — he would turn the very nature of the genre inside out, to utterly astounding effect.

Gotham Central

While Joker's vision of a down-at-mouth Gotham City is unique, this take on the city of the big black bat has a long history in the comics. Gotham has had a wide variety of bleak tales told within its crime-crowded borders. There's a reason so many Batman stories revolve around well-connected mobsters, politicians, and erstwhile society scions like the Penguin — Gotham's the kind of city where corruption flourishes. No wonder Batman has to be the world's greatest detective in addition to a peak performance athlete, martial artist, and repeat father figure to a flock of Robins and Batgirls.

But Batman isn't the only good guy with Gotham's citywide decay in his sights. 2002's Gotham Central examined Batman's world from the seat of the GCPD's Major Crimes Unit, whose work ranges from serial murder to figuring out just how to handle policing a city with a pointy-eared vigilante doing their work for them. Over the course of 40 issues, readers explored the panic and disarray of a city terrorized by the Joker, Mr. Freeze, and Poison Ivy at the street level, where crime-busting is something that happens within many shades of gray. With a steely star portraying protagonist Renee Montoya and a director with vision, Gotham Central could examine its titular city in an unprecedented way: as a place where ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances work, play, and somehow survive.

The Question

The Question began with Steve Ditko's Objectivist ideals, and his journey from those origins has been strange indeed. Originally created for Charlton Comics in 1967, he joined the DC universe alongside other Charlton heroes in the 1980s. Though he is very much a hero, his approach to doing good is often notably murky. He doesn't kill, but he certainly considers it and often finds himself far less bound by a fear of crossing an ethical line than, say, Batman. His mask doesn't just obscure his identity, but his very humanity — something he very intentionally goes for. There is an edge to the Question, a line he dances across in his desire to root out venality and corruption wherever it hides. He's a good guy, but not too good. Unexpectedly, Justice League Unlimited proved that he works as well on his own as part of a group, especially when paired in an unlikely romance with the cunning Huntress. The Question is the voice of society's conscience that no one wants to hear, the fringe theorist whose hole-poking will only be vindicated by the passage of time. He's not someone you'd necessarily want to be friends with, but you're glad he's around — alone, but undeterred.

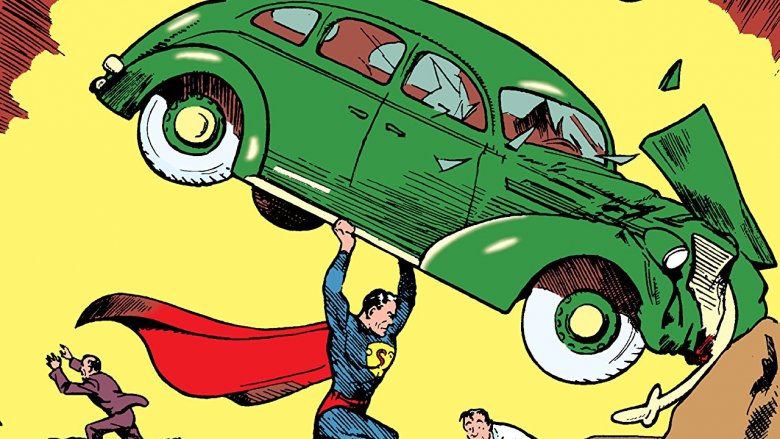

Superman, 1938

Superman is, of course, the superhero. His arrival created a genre, cemented an art form, and, ultimately changed the course of history. His stories number in the thousands, his fans in the millions. He is an icon whose flexibility — is he Jesus? Moses? The United States? An impossible vision of world peace? The ultimate immigrant? — has, somehow, never dimmed his luster.

Yet he is also a singular character with a unique backstory, set of abilities, and personality. What better way to take a fresh approach to the man in the cape than to go back to the beginning and explore him in one of his earliest roles: late 1930s urban crusader? Many of his earliest comics saw Superman tackling social ills from corruption to domestic violence, rooting his goodness in everyday life. Why not, in fact, tell a Superman story in that era? Imagine Superman as a boy molded by the Depression as it unfolded in rural Kansas, taking on the underserved populace of the shining city he's moved to. Imagine the power of a portrayal that strips the character down to its earliest essence, and in so doing, finds him all the more potent? Superman is an alien, a savior, and a force for good. And sometimes, the best way to express that is by showing him helping people on the ground as a guy in a cape who just wants to make the world a fairer place.