Scenes Movie Studios Secretly Deleted

It isn't often that directors get the final say on the theatrical cut of their films. It isn't often that every single joke in a movie lands. It's rarer still that every joke, line, or scene from a movie has aged well. As such, it's more common than most would think that the movies we love have been edited before release. Sometimes the edit is small — removing a scene here and there — and other times it changes the meaning of the entire movie.

Advances in film technology have made removing scenes easier than ever, but from Hollywood's earliest days, studios have exercised control over the movies they put out — occasionally even mandating reshoots without bothering to tell the director. When these last-minute changes occur, they can create tension, make the film better — or sometimes even save lives. With all that in mind, here's a look at some noteworthy scenes that studios secretly deleted.

Wayne's World sees Stairway denied twice

Anyone watching Wayne's World on television or home video has seen the following scene: Wayne Campbell (Mike Meyers) playing four random notes on a guitar and being interrupted by a music store employee pointing to the "No Stairway to Heaven" sign on the wall, followed by Wayne saying, "No Stairway — denied!"

This is confusing, because the notes Wayne is heard playing sound nothing like "Stairway to Heaven." But they once did, in theaters, and haven't sounded like it since. This is because the surviving members of Led Zeppelin got involved and forced the change.

Led Zeppelin are notoriously picky about their music being used in movies, with Jack Black famously begging the band onstage to let him use "Immigrant Song" for School of Rock. They were much less willing in the early '90s, even if the butt of the joke is "music store personnel are sick of hearing amateurs butcher Zeppelin."

The original theatrical cut of the film shows Wayne clearly playing "Stairway," but the filmmakers found out playing more than three notes would result in a licensing fee of $100,000 — far more than the relatively low-budget production could afford. The notes were changed when the movie was released on home video, simultaneously ruining the joke and metatextually enhancing it.

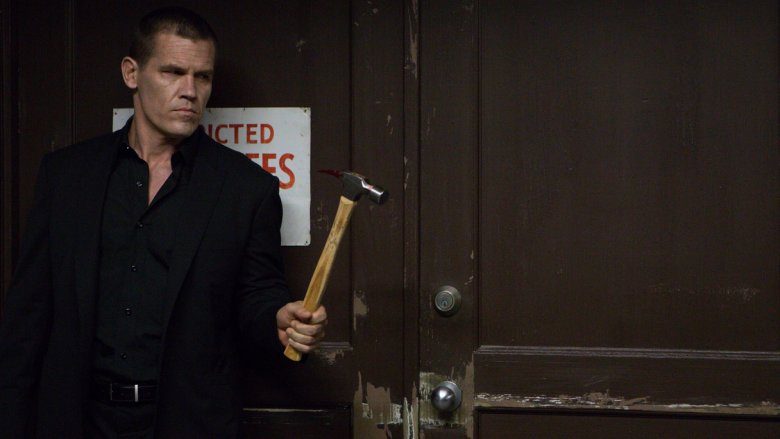

Spike Lee's Oldboy hammer scene is edited

One of the most memorable scenes in Park Chan-wook's Oldboy is the three-minute, one-take side-scrolling shot in which the main character faces a throng of enemies using only his wits and a hammer. It's a scene Spike Lee looked to replicate in his 2013 English language remake, but the studio cut it — and nobody would have noticed if Lee didn't say anything.

Lee didn't plan on doing a shot-for-shot remake, but there were some scenes from the original that were impossible to avoid. The hammer fight was one such scene, and Lee talked publicly about how he and star Josh Brolin planned on executing it. Brolin trained for weeks, Lee added a new level to the staging, and they got it in one take. Oldboy wasn't a standard Spike Lee Joint, though — it was a studio movie, and parts of it were out of Lee's control.

Just a couple of days before the movie opened, Lee told the New York Times that there was a cut in his hammer fight. "Shouldn't be, but there is a cut," Lee lamented, adding, "There's no reason to try and even attempt that shot unless it's a one-take. That's the scene from the original! That's the scene!"

Asked why it was altered, Lee offered two words: "Tough business."

A dirty phone number was cut from The Santa Clause

Towards the beginning of The Santa Clause, Scott (Tim Allen) is given a piece of paper containing a woman's phone number. "1-800-SPANK-ME?" he quips. "I know that number." It's a slightly edgy joke for a PG movie, but no kid would understand it and it was just a quick throwaway gag. At least that was the thought at the time — now, one would be hard pressed to find the scene.

Shortly after the film's release, reports emerged that children were calling the number only to find out it led to a phone sex hotline. At the time, Disney reps brushed it off by saying they couldn't imagine people actually calling — and "If a real number like that exists, it's coincidence."

After the movie was released on home video, reports trickled in of kids calling the number. With no way for the line to confirm if the caller was 18 or over and the option to charge the phone bill in lieu of a credit card, parents ended up racking up phone bills worth several hundred dollars. Parents wanted the movie recalled and the phone line disconnected.

In late 1997, the Orlando Sentinel confirmed that Disney had quietly removed the scene from new copies of the VHS and all television airings. They decided against a full recall, fearing it would only draw more attention to the number, but it hasn't appeared on any version of home video since. Copies of the joke can still be found on YouTube, ripped for old VHS copies and the Laserdisc edition. Disney also attempted to buy the phone number to disconnect it.

Richard Nixon orders a scene cut from 1776

The story of the Second Continental Congress set to music, 1776 debuted on Broadway in 1969 and won the Tony Award for best musical that year, edging out Hair. In 1970, the cast received an invitation to perform at the Nixon White House — and a demand that they cut the song "Cool, Cool Considerate Men" from the show. The song features wealthy conservative members of the Continental Congress sing about swaying the country "to the right" and includes lines such as "Don't forget that most men with nothing would rather protect the possibility of becoming rich than face the reality of being poor." The production stood its ground and performed the song at the White House anyway.

Two years later, Jack Warner produced the film version of 1776. Once the movie was in post-production, director Peter H. Hunt went on a trip to Europe. When he came back, he found out that Warner — a Nixon friend and supporter — had screened the film at the White House, and Nixon once again demanded "Cool, Cool Considerate Men" get cut. This time he got his wish. When Hunt asked Warner how he could do such a thing, Warner responded, "With a pair of scissors."

Reviews complained that the movie lacked bite, which can partially be attributed to the deleted scene. Fortunately, it was restored for the director's cut DVD.

A Hobbs & Shaw teaser was cut from Fate of the Furious

The Fate of the Furious was supposed to end with a tag setting up the franchise spinoff Hobbs & Shaw, but it was left on the cutting room floor. There's a good chance it's because the Rock and Vin Diesel were feuding.

In the middle of the film, Hobbs (Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson) and Shaw (Jason Statham) express mutual admiration before agreeing that when their task is over they're going to settle things via combat. Their chemistry was so good that the producers shot a scene in which they squared up for a fight before realizing that they should be working together. The idea was to use it as a setup for a then-theoretical spinoff.

TheWrap reported that the scene was filmed without Diesel's knowledge. When he found out about the scene during early screenings, he allegedly called Universal execs and forced them to cut the sequence. Another source indicates that the scene was cut because producers thought it might be more useful elsewhere or as a home video extra. Either way, no commercial audience has laid eyes on it — but Hobbs & Shaw did well enough without it, either way.

A casting couch joke is cut from Toy Story 2

Pixar re-released the Toy Story trilogy in the buildup to Toy Story 4, but with a tiny cut to Toy Story 2 that the studio never announced and few would have noticed if not for the franchise's generations of dedicated fans.

Toy Story 2's end credits featured a mock blooper reel that included Stinky Pete flirting with two identical Barbie dolls and saying, "You know, I'm sure I could get you a part in Toy Story 3." The re-release spikes that scene entirely and just moves on to the next mock blooper. No announcement was made about the cut, and it was only noticed by studious fans when comparing cuts.

The scene was understandably removed after the #MeToo movement gained steam and casting couches really entered into the public consciousness. Pixar's own John Lasseter left the company after sexual misconduct allegations against him went public. Tastes change, and so do our standards for what's socially acceptable to joke about — particularly in a family-friendly film.

Greed's story is redistributed

Released in 1924, Greed was one of the biggest movies of the silent film era, both in terms of impact and sheer volume. Erich von Stroheim thought he'd made his masterpiece — but more than half of it was cut by the studio without his permission.

Only 12 people ever saw the original 42-plus-reel eight-hour cut. Some called it the best film they'd ever seen. Others lamented that von Stroheim insisted on putting "every comma" from the book into the movie. Ultimately, Von Stroheim cut the film down to 24 reels, which mapped out to about four hours. He considered this the tightest cut possible. MGM thought otherwise and brought in a new editor — without telling Von Stroheim — to bring it down to 10 reels and 140 minutes. Von Stroheim never forgave MGM for cutting his beloved project.

In 1999, a reconstructed four-hour version was released by Turner Entertainment. It features still photographs of the lost scenes, and attempts to follow the shooting script. The full eight-hour version is presumed lost forever.

The Program loses a scene after people start copying it

A 1993 sports drama starring James Caan, The Program is a mostly forgotten movie about the pressures a college football team faces trying to make a bowl game. By the time it hit home video, reviews were already talking about how the most memorable part of the movie was the part that got cut after real life tragedy.

In the scene in question, one of the characters attempts to prove his bravery by lying down on the dividing line on a busy road. Eventually the rest of his teammates join him to show how focused they are under pressure. Shortly after the film was released, reports of dozens of people trying the stunt rolled in, including at least one confirmed death and several injuries. Touchstone Pictures put out a statement saying "The scene in The Program clearly depicts this adolescent action as an irresponsible and dangerous stunt by a troubled and heavily intoxicated individual, and in no way advocates or encourages this type of behavior."

By the time The Program hit video, the studio had removed the scene. It has never been restored since, but it was available on the Hong Kong video release, and in 2012, the missing footage surfaced on YouTube.

Wild Rovers loses 40 minutes

In between directing installments of the Pink Panther franchise, Blake Edwards wrote and directed a 1971 western called Wild Rovers. Working with an all-star cast that included William Holden, Ryan O'Neal, Karl Malden, and Joe Don Baker, Edwards wanted to make a three-hour epic with a downer ending. The studio had other ideas.

After cold receptions to test screenings, MGM stepped in and cut about 40 minutes of material without Edwards' approval. They also changed the ending, making it more uplifting. Edwards was unhappy, telling MGM, "There was no discussion; an integral part was simply removed.... if I take a chair and remove one leg, you still have a chair, but it won't stand up, will it?"

Critics and audiences agreed — reviews were disappointing and it fared poorly at the box office. Edwards, still upset that they "cut the heart out" of his film, secured final cut for his next production, The Carey Treatment. The studio interfered anyway, and he sued for breach of contract.

The Magnificent Ambersons was cut while Welles was away

Orson Welles knew he had something special with The Magnificent Ambersons, his follow-up to Citizen Kane — in fact, he he openly said he was "more sure of its value... than of Kane." To this day, it's regarded as one of the better pictures ever made, but that's in spite of the studio secretly re-editing it when Welles was out of the country.

Welles had to be in Rio after production, so he arranged for editor Robert Wise to get the final cut and fly out and join him with it so they could shape it together. Travel restrictions meant that Wise could only mail a copy to Welles. Via phone calls and wires, Welles offered cutting instructions, but the studio had other plans.

Worried about the 132-minute length and eager for an Easter release, they gave the film a preview screening and got a mixed reaction, so the studio heads arranged for reshoots and re-edits. Welles protested, but RKO claimed that Welles altered his contract and lost the right of final cut. In the end, RKO ended up with an 88-minute film and Welles lost much of his movie, including a striking epilogue.

Touches are taken from Touch of Evil

The Magnificent Ambersons was the start of a post-Kane pattern for Orson Welles — one in which he repeatedly started out with a specific vision, only to have the studio butcher it. Touch of Evil was no exception, and years later, there remain multiple versions of varying lengths, none of which quite match what Welles had in mind.

The studio took a risk on Welles, who by this point had a reputation of being difficult for executives. Much of the editing techniques were ahead of their time, including scenes out of chronological order to offer insights into actions yet to be shown. When studio executives saw a cut of the film, they hated it, and responded by barring Welles from the editing bay and hiring someone new to recut the movie.

After Touch of Evil flopped, Welles and Hollywood gave up on each other; he spent most of the rest of his days making movies overseas. Film historians and fans have spent years comparing production notes to find out which scenes were cut and which scenes are lost.

Metropolis is butchered over and over

The 1927 classic Metropolis is often considered the first feature-length sci-fi movie. Today, it's considered Fritz Lang's masterpiece, but at the time, it was controversial — after its release, the three-hour original came under criticism for a variety of reasons, and it was cut multiple times.

American studios found the movie too long and tedious, so they hired playwright Channing Pollock to re-script and re-edit the film. This version ran for just shy of two hours. Character names were changed, intertitles were altered, and motivations became less clear. Upon hearing this, Lang said, "I love films, so I shall never go to America. Their experts have slashed my best film, Metropolis, so cruelly that I dare not see it while I am in England."

Another such edit was made at the behest of Alfred Hugenberg, a wealthy German national who later became one of Hitler's financial backers. The edit in question removed many religious references as well as any "communist tendency." Much of the excised footage was considered lost, but a fair number of it has been retrieved by good fortune. Footage found in 2008 answered several lingering questions about the plot, including explaining character motivations and making some scenes "much more dramatic" than what had been seen to that point.