Major Crimes That Happened On Set

The history of cinema is filled with crime, both in front of the camera and behind the scenes. Not everybody gets peace and quiet once the director yells "cut," however. Cover-ups, mobsters, and the occasional unstable actor have resulted in just as much intrigue. Sometimes the crime is baked into the making of the movie, and sometimes the crime is just something that happened by accident but was nonetheless a crime. Sometimes it's the result of a personality clash, and sometimes it's the result of a director getting the shot they need by any means necessary — especially if it's Werner Herzog.

The list you're about to read aren't simple "falsified his timecard"-level crimes, though — they're major, ranging from a director threatening an actor to outright bribery to tragic accidents gone horribly wrong. Here's a look back at some of the most noteworthy times major crimes were committed on the set.

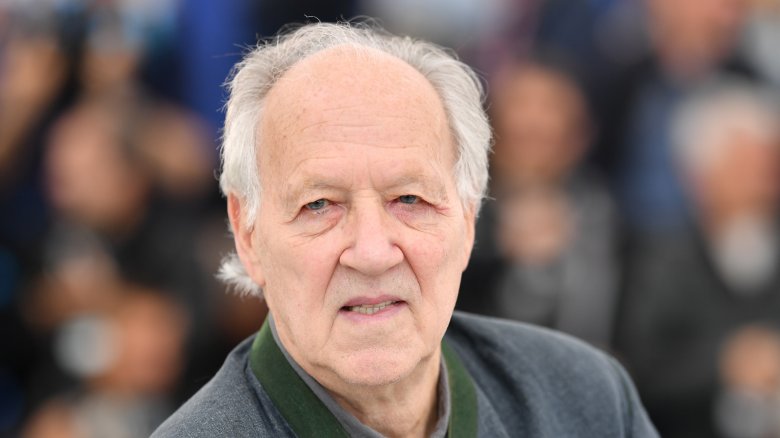

Werner Herzog defies military orders

Werner Herzog has long had issues with the concept of "laws." He stole his first camera from a film school. He proudly states that he "was shot at... while filming crossing illegally a border from Honduras into Nicaragua." A piece of advice he offers to filmmakers is "There is nothing wrong with spending a night in jail if it means getting the shot you need," and he proved that on his first ever feature, Signs of Life.

Herzog secured permission to film in Greece, but just before production there was a military coup in Greece. It was the start of the Greek military junta and all of his permits became meaningless. Eventually things settled down — at least politically; the production itself was still a nightmare — until he had to shoot the climax, which required fireworks, something the military forbade. Herzog pleaded his case and was told that if he used fireworks he'd be arrested. He responded: "Go on and arrest me. But I won't be without a firearm tomorrow." He threatened to shoot any man who tried to arrest him. The next day, dozens of police officers and several thousand locals reportedly came to watch the fireworks. Nobody laid a hand on Herzog. He threatened a major in a military dictatorship and came out unscathed.

He'll show up later on this list, too.

The cast of Titanic is dosed with PCP

The hallmark of any James Cameron movie, perhaps more than any stylistic choice, is a long and disastrous production cycle. Titanic was no different, with the most infamous example being the day the crew ate chowder spiked with PCP.

On August 8, 1996, the crew was filming in Nova Scotia when they broke for lunch. Of particular note was the chowder, described by set painter Marilyn McAvoy as so good that people were going back for seconds. Half an hour later, everyone who ate the chowder began acting strangely. Cast member Bill Paxton recalled that "Some people were laughing, some people were crying, some people were throwing up." Thinking they'd all experienced food poisoning, 60 to 80 people were brought to the local hospital. Too anxious to sit still, the crew started racing wheelchairs in the hallways. Cinematographer Caleb Deschanel started a conga line.

Everyone was given liquid charcoal to remove toxins, and they'd all come down by dawn. Eventually the toxicology report came back: the chowder was laced with PCP. The case was closed on February 12, 1999, due to a lack of suspects. Rumors amongst the crew suggested a disgruntled chef was the culprit. The catering company's CEO blamed "the Hollywood crowd" trying "a party thing that got carried away." Cameron believes it was a crew member they fired the day before for "creating trouble with the caterers" exacting revenge.

Werner Herzog threatens to kill Klaus Kinski

Klaus Kinski was famous for his brilliant performances, but perhaps more famous for his temper. Stories of his on-set tantrums are legendary, and everyone from crew members to his own family lived in fear of him. The only director he couldn't irrevocably alienate was Werner Herzog, with whom he made five movies. Herzog said of their relationship, "[w]e had mutual respect for each other, even as we both planned each other's murder." That's not hyperbole, either.

Kinski's behavior during their first collaboration, Aguirre, Wrath Of God, set the tone for their relationship. Kinski was such a nightmare on set that the crew almost walked off at least once. Once he was so upset at the sound of the crew playing cards during a break that he blindly shot a rifle at them. At one point the Peruvian Indians, who acted as extras in the movie, approached Herzog and offered to kill Kinski. Herzog declined, at least in part because he still needed to finish the film.

Still, that doesn't mean Herzog wasn't willing to take matters into his own hands if necessary. At one point, Kinski packed his bags and was ready to walk off the set, and Herzog pulled a gun him and demanded he finish the movie. In Herzog's own words: "I told him I had a rifle and that he'd only make it as far as the first bend before he had eight bullets in his head — the ninth one would be for me." Kinski stayed.

Years later, Herzog tried and failed to firebomb Kinski's house. Kinski also tried to kill Herzog at some other indeterminate point. The two had a laugh about it.

Sahara included bribes in its budget

Saraha, the 2005 adaptation of Clive Cussler's novel of the same name, is primarily remembered as a bomb, which is both accurate and unfair. The movie made $119 million against a $160 million budget, so by any empirical measurement it was a box office bomb. That said, the movie debuted at No. 1 and stayed in the top five for four weeks. It also finished 35th overall for domestic gross on the year, in the same zip code as hits such as Sin City and Herbie: Fully Loaded. Clearly that big budget prevented it from breaking even, so why was it so expensive?

In 2007, as a result of a lawsuit over the film, we got our answer: misplaced priorities — and bribes set aside for the Moroccan government. These bribes are not "alleged" or rumors. The phrase "local bribes" appeared verbatim as a line item in the budget. The Los Angeles Times examined the budget for the movie and found "'Courtesy payments,' 'gratuities' and 'local bribes' totaling $237,386 were passed out on locations in Morocco to expedite filming." This includes a nearly $41,000 payment to stop a river improvement project that would have impeded production. Also included was money earmarked for "political/mayoral support."

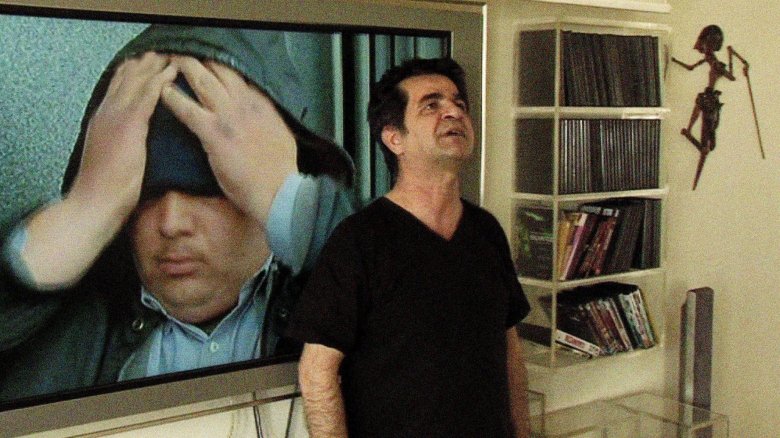

This Is Not A Film, but it is a crime

Iran's film scene has long been regarded as one of the world's best, and it often comes into conflict with the country's strict government. Jafar Panahi is Exhibit A. He's one of the most acclaimed Persian filmmakers with a worldwide fanbase, but has frequently run into problems within his own country. This all came to a head in 2010, when he was arrested and charged with making propaganda against the Iranian government. He was sentenced to six years house arrest and handed a 20-year ban on making movies, writing screenplays, or giving interviews.

Panahi responded to this by... making a movie. The crime wasn't just on set, the crime was the set itself. Thus, This Is Not a Film.

According to Panahi's own interpretation of his sentence, the ban never put a restriction on him telling his own story. Shot on an iPhone and a digital camcorder, Panahi tells his version of what happened and takes viewers through a day in the life of his house arrest. The completed movie was put on a flash drive, hidden inside a cake, and smuggled out of Iran.

The Twilight Zone helicopter accident

One of the most infamous on-set accidents in movie history, the Twilight Zone helicopter fatality also revealed a series of crimes and falsehoods behind the tragedy.

On July 23, 1982, John Landis was filming a scene for the Twilight Zone movie in which Vic Morrow would carry two children — Renee Shin-Yi Chen and Myca Dinh Le — while being chased by a helicopter. A mortar effect fired too early and knocked the tail rotor off the helicopter, causing it to crash and killing Morrow and the children.

Years of litigation revealed numerous crimes on set. The children were hired without permits and worked after nightfall, illegal even under better circumstances. The families were paid in cash to cover up the lack of permits. Landis was also warned by both the helicopter pilot and the camera operator that the stunt was too dangerous, but shrugged it off.

The families of the children and the Morrow estate each settled for or collected damages in civil court. Landis and several other co-defendants were found not guilty of manslaughter in 1988, and Landis thanked the jurors by inviting them to a private screening of Coming to America.

Connery fights a gangster during During Another Time, Another Place

Years before Sean Connery played James Bond, he had a reputation for toughness borne out of years of hard living. He spent time as a bodybuilder and an athlete, and in one of his first big roles onscreen, he showed off his fighting prowess by fighting a mobster.

Another Time, Another Place (1958) saw Connery starring opposite Lana Turner. Off the set, they were often seen out and about together, and rumors began to spread of a relationship. This rumor spread back to America and came to the attention of Johnny Stompanato, a bodyguard for mobster Mickey Cohen — and Turner's jealous boyfriend.

Stompanato flew out to England and stormed onto the set during filming, pointing a gun at Connery and demanding that he stay away from Turner. Connery responded by knocking the gun out of Stompanato's hand and knocking him down with a right hook. Shortly after, Stompanato was kicked out of England by Scotland Yard for having an illegal firearm; several months later, he was stabbed to death by Cheryl Crane, Turner's daughter, who was protecting her mother. For a short period of time, the mob thought Connery might have been responsible, leading him to lay low for a while.

Suge Knight runs over two people on the Set of Straight Outta Compton

Wherever Suge Knight goes, trouble seems to follow — largely because he's the one who seems to cause it. The founder and former CEO of Death Row Records has a long history of jail terms, parole violations, outstanding warrants, alleged death threats, robbery charges, and various altercations. He's also long been rumored to have a hand in the slaying of both the Notorious B.I.G. and Tupac Shakur.

During the filming of Straight Outta Compton in 2015, Knight committed the crime that will likely see him live the rest of his life behind bars: vehicular manslaughter.

Knight got into an argument with two men he knew well, Terry Carter and Cle Sloan, on set. After the argument, Knight tracked the two men down at a nearby burger stand and crashed into them with his car. Sloan was injured but recovered, and Carter was killed. After years of litigation, Knight pleaded no contest and was sentenced to 28 years in prison.

Andre Royo is given heroin on the set of The Wire

The Wire may never have gotten any Emmy love or huge ratings, but is still remembered as one of the most acclaimed television shows in the history of the medium. One of the points of most praise is the show's realism – showrunner David Simon was a journalist in Baltimore for years, and the writers made sure that the show always felt true to reality. One time it was so realistic that it resulted in an actor being given a Schedule I drug.

Actor Andre Royo portrayed Bubbles, a homeless drug addict and police informant. Production took place on location in Baltimore, often in the violent and poverty-stricken sections of the city it portrays. One day during shooting, a man approached Royo, pressed a package into his hand, and said "man, you need a fix more than I do." Royo opened his hand and found the package of heroin he calls his "Street Oscar."

Extras might have drowned during Noah's Ark

Noah's Ark (1928) is an early Hollywood epic famous for three things: One, being an early work of Michael Curtiz, who'd go on to direct Casablanca; two, featuring a young John Wayne as an extra; and three, injuring if not outright killing many extras during the flood scene.

Cinematographer Hal Mohr approached Curtiz and said that they could easily create the scene using miniatures and camera tricks. Curtiz rebuffed him and wanted to film without special effects. Instead, his crew set up a massive contraption that would pour about a million gallons of water onto the set. He didn't inform the extras about his plans, and when Mohr confronted him, Curtiz reportedly said, "Oh, they're going to have to take their chances."

The end result was a spectacular shot, but the water hit with such violence that it injured countless cast members. Dozens of ambulances were required. At least one victim ended up with pneumonia, many bones were broken, one person lost a leg, and more than one suffered injuries from which they never recovered. The rumor on the set at the time was that someone was killed; years later, a stuntman claimed there were three fatalities. Daily production reports from the set are missing, which might indicate a coverup, but all of this happened before the formation of the Screen Actors Guild, so the actors had no protection anyway.

The mob interferes with the making of The Godfather

The Godfather (1972) is a movie that needs no introduction. Often hailed as one of the best movies ever made, it not only influenced every form of crime media released since, but it influenced the way the mob saw itself. Part of this is the result of the mob interfering in the production of the movie.

Front and center in protest against The Godfather was the Italian-American Civil Rights League (IACRL), a group that ostensibly formed to fight Italian American stereotypes in media. IACRL was actually an arm of the Colombo crime family, and they set their sights on the new mob movie being made. They started a campaign, combining behind-the-scenes harassment while rallying law-abiding citizens for regular protests. IACRL implied the production would have "labor issues." Expensive equipment kept getting stolen off the set. Producer Al Ruddy's car had its windows smashed.

Eventually Paramount executive Robert Evans got a threatening phone call, which was the final straw. A meeting with Joe Colombo, head of the Colombo crime family, was arranged, and they came to an agreement — the words "mafia" and "la casa nostra" would be stricken from the script, and the production went on unimpeded.