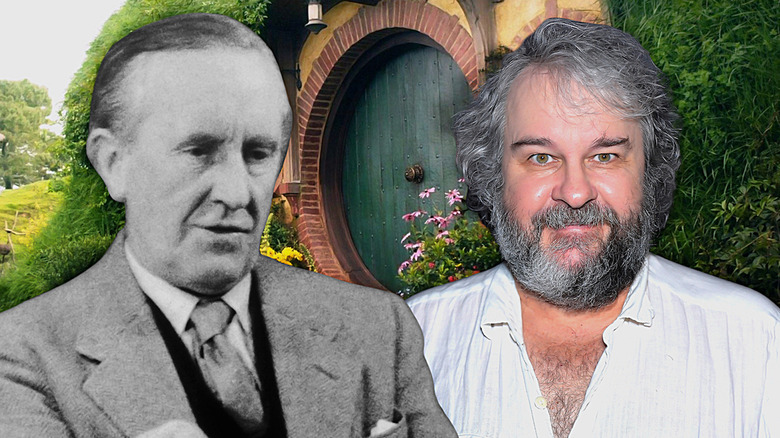

5 Lord Of The Rings Movie Changes Tolkien Hated - But Peter Jackson Did Anyway

Peter Jackson's "The Lord of the Rings" trilogy is a landmark moment in cinematic history. The trilogy from the turn of the century ushered in an era of high-fantasy entertainment and has remained a benchmark for excellent adaptive efforts ever since.

And yet, Jackson's movie adaptations aren't perfect. Far from it. Book readers, in particular, often have to bite their tongues as they watch. Jackson's films are filled with plenty of confusing moments that don't happen in the "Lord of the Rings" books, such as Elves showing up at Helm's Deep and the Army of the Dead sweeping across the Battle of the Pelennor Fields.

These moments rankle fans familiar with Middle-earth, and there's one critic to rule them all who would doubtless be more upset than anyone else at these inconsistencies. J.R.R. Tolkien was a notoriously detailed author and world-builder. In his foreword to "The Fellowship of the Ring," he says, "The most critical reader of all, myself, now finds many defects, minor and major" — and that was in reference to his own writings.

When it comes to a screenplay, we have a fascinating glimpse into Tolkien's take on adapting his source material for the silver screen in a lengthy letter he wrote in 1958. The massive memorandum thoroughly critiques a proposed script to adapt his trilogy, and he apologizes for the irritated and resentful tone of the reply before launching into a detailed and brutal analysis.

While that movie was never made, there are several points throughout the letter where Tolkien specifically calls out issues that bring to mind Jackson's adaptations. Whether the director read the letter or not, there are several things that Tolkien criticizes that the director did anyway. Here are a few of the most glaring alterations.

The use of irrelevant magic

In his adaptive analysis, J.R.R. Tolkien gives a clear injunction to knock off any nonsense. Middle-earth may be a fantasy world, but the author takes it very seriously, and early in the letter he states that the script has introduced multiple nonsensical elements, "not to mention incantations, blue lights, and some irrelevant magic (such as the floating body of Faramir.)" In the next sentence, he adds that the screenplay also shows an excessive penchant for fighting.

While Peter Jackson doesn't go so far as having a floating body for Faramir, he definitely dabbles in the department of unnecessary magic. The most obvious example of this is when Gandalf (Ian McKellen) and Saruman (Christopher Lee) engage in a Wizard duel in Orthanc early in "The Fellowship of the Ring." The scene depicts the two magic-wielders blasting one another with unseen enchanted bursts of physical power. They send each other flying to and fro, and eventually, Saruman uses his unseen power to whip Gandalf's staff right out of his hand. He levitates his grey-clad companion in a spinning trap before sending him flying up to the roof of his tower.

For comparison's sake, here's how Tolkien describes Gandalf's capture in his book: The Wizard reports to the Council of Elrond, "They took me and they set me alone on the pinnacle of Orthanc." That's it. No bewitching glitz or spellbinding glamor. Tolkien's magic is subtle. It's down-to-earth. Sure, there are a couple of explosive magical manifestations from time to time, like Gandalf's dramatic fireworks or his glowing staff that guides the Fellowship through Moria. But there are no action-heavy Wizard duels. Apparently, Jackson couldn't resist the temptation to have the two Wizards express their disagreement (and their magic) in a more physical, visceral manner.

Aragorn's aggressive introduction

When Aragorn enters the story in the Prancing Pony at Bree, Peter Jackson has Viggo Mortensen's character come in swinging. He initially appears to threaten Frodo (Elijah Wood) and his companions and even draws his sword when Sam (Sean Astin), Pippin (Billy Boyd), and Merry (Dominic Monaghan) come bursting in to confront him.

Again, this goes against J.R.R. Tolkien's injunction not to over-saturate the story with action and violence. The Oxford Don also explicitly states, "Strider does not 'Whip out a sword' in the book. Naturally not: his sword was broken." Thats right. When Strider first hooks up with Frodo and company, he is already carrying his broken heirloom – Aragorn's sword, Anduril, is ancient and very important, and he doesn't leave it lying around, not even on statues in Rivendell. This contrasts with Jackson's depiction of Strider whipping out fully assembled swords in undersized bedroom parlors in Bree.

Aragorn doesn't even have a sword when he confronts the Black Riders. Tolkien addresses this, asking why he whips out a sword, adding, "Why then make him do so here, in a contest that was explicitly not fought with weapons?" He also says that the Black Riders don't scream during the Weathertop battle since they are working in terrifying silence (Jackson has them scream as they approach the hill) and summarizes, "There is no fight." He condemns the need for swordplay and action, calling it "yet one more scene of screams and rather meaningless slashings." From drawing swords to dueling Black Riders, Aragorn's aggressive early role in Jackson's films is definitely not in line with Tolkien's vision.

The exaggerated power of lembas

At one point, J.R.R. Tolkien tackles the adaptive decision to represent lembas. In the screenplay, the magical source of sustenance is treated as a sort of superfood, and the author doesn't allow it. He says, "Lembas, 'waybread', is called a 'food concentrate,'" adding that along with avoiding the silly fairy-tale concept, "I dislike equally any pull towards 'scientification', of which this expression is an example. Both modes are alien to my story. We are not exploring the Moon or any other more improbable region. No analysis in any laboratory would discover chemical properties of lembas that made it superior to other cakes of wheat-meal."

Far from a practical meal prep program, Tolkien hints at the power of lembas in "The Return of the King" book when he explains that it has a virtue that doesn't satisfy desire. The author says it has a potency of its own, elaborating, "It fed the will, and it gave strength to endure, and to master sinew and limb beyond the measure of mortal kind."

When Jackson first introduces lembas in a deleted scene for "The Lord of the Rings" extended editions, Legolas (Orlando Bloom) says of the stuff, "one small bite is enough to fill the stomach of a grown man," after which Pippin reveals that he ate four full cakes of the stuff. If that isn't 'scientification' at its finest, we don't know what is. It ignores the magical properties of the unique food item, opting instead to categorize it as a super-concentrated form of nutrients — precisely what Tolkien rejected.

Maintaining coherent sequences

Once the Fellowship of the Ring breaks up at the end of the first movie, the event splits the story down the middle. Half of the narrative follows Frodo and Sam on their journey to Mount Doom. The other half keeps track of the rest of the heroes as they resist Saruman and Sauron's military might. J.R.R. Tolkien presented these, more or less, in isolated chunks. The first half of "The Two Towers" book, for instance, is all about the heroes' adventures with the Ents and Rohirrim.

The second half exclusively focuses on Frodo and Sam's journey to Mordor and their initial confrontation with Shelob. In the letter, Tolkien highlights the importance of maintaining this approach. He explains the narrative taking on two main branches and says, "It is essential that these two branches should each be treated in coherent sequence." The author justifies this need by adding, "Both to render them intelligible as a story, and because they are totally different in tone and scenery. Jumlbing them together entirely destroys these things."

Tolkien makes the case for coherent storytelling that focuses on specific groups of characters for longer periods of time. It is a wise approach that is used in the books and which Peter Jackson completely throws to the wind. "The Two Towers" and "The Return of the King" are filled with sudden shifts as the narrative constantly bounces back and forth between Frodo and Sam and the rest of the Fellowship. It's masterfully done, and the story remains surprisingly coherent, but it doesn't change the fact that it is a stark deviation from Tolkien's deliberate storytelling modus operandi.

Altering the end of the book

It's no surprise that the movie adaptation had to cut certain elements of J.R.R. Tolkien's original story as he went along. There are obvious candidates to get the axe, like Tom Bombadil's side quest (although Peter Jackson did hint at Bombadil in a later deleted "Two Towers" scene). One glaring omission is the removal of the entire ending of "The Return of the King" book.

In it, the four Hobbit heroes return home to find that Saruman's minions have turned the Shire into an oppressive, industrialized nightmare. They rally the Hobbits and drive out the invaders in an event called "The Scouring of the Shire." Saruman is killed by Wormtongue (Brad Dourif), who himself is shot by Hobbit archers. It's only then that the Hobbits begin to rebuild their broken home.

All of this is absent from Jackson's adaptations. Saruman and Wormtongue are bumped off in a deleted scene early in "The Return of the King," and the Shire is A-OK when the Hobbits get home at the end of the movie. And yet, Tolkien thought this was a bad idea. In the letter, the professor protests, "[The screenwriter] has cut out the end of the book, including Saruman's proper death." To be fair, he does add that if truncating the finale is needed, Saruman should be left alive, stewing in his own misery, and until Jackson released his extended edition of "The Return of the King," he completely ignored the end of the fallen Wizard. Once he added it back in, though, it re-highlighted how the end of his trilogy completely skips over the splashy Shire war and its significant repercussions.