Velvet Buzzsaw's Ending Explained

Works of art can be very perplexing, and sometimes, they can knock you dead. Netflix's Velvet Buzzsaw takes that idea and runs with it, bringing art pieces to life that take their audiences' breath away — permanently.

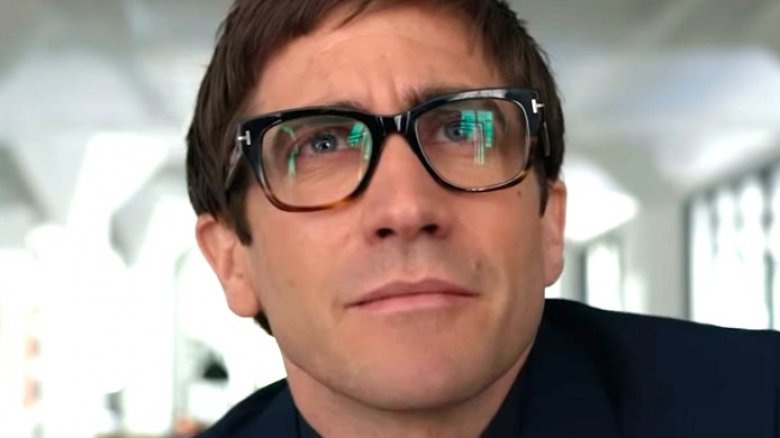

The third film from writer-director Dan Gilroy, Velvet Buzzsaw is a satirical horror-comedy that turns its critical gaze on the art world, skewering the gatekeepers who determine what kind of art gets to be successful. The movie is a reunion for Gilroy and co-stars Jake Gyllenhaal and Rene Russo, who previously worked together to great effect in Gilroy's directorial debut, Nightcrawler. Is it as good a movie as that highly regarded new classic? That's up to you. But much like Nightcrawler, Velvet Buzzsaw is a movie with a message, inked in blood.

Some of the movie's themes are pretty obvious, but much like the curse at the center of the story, the devil is in the details. If you're having trouble figuring out what this film is trying to say, worry no more. Sit back, enjoy a drink, and for your own sake, don't touch anything as we break down the bloody end of Velvet Buzzsaw.

Final exhibition

Don't be fooled by the glossy sheen of high art atmosphere and a generous budget. At its heart, Velvet Buzzsaw is as trashy of a slasher movie as any given installment of Friday the 13th. Actually, a more accurate description would peg this movie as an art world version of Final Destination. Instead of the victims being generally unsympathetic cookie-cutter teens, they're uniquely loathsome, insufferably pretentious grown adults. You're flat-out not supposed to like them, which makes it all the more sickly enjoyable, when the time comes, to sit back and watch them suffer.

Much like Final Destination, this is essentially a slasher movie with a metaphysical villain. In the Final Destination series, the enemy is Death itself. In Velvet Buzzsaw, things are a little bit more complicated. Here, the killer is the vengeful spirit of a deceased artist, Vetril Dease, persisting from beyond the grave to lethally punish all those who would seek to profit off of his and others' art.

Killer comedy

Velvet Buzzsaw is not a particularly scary movie. As far as genre goes, it's best categorized as a horror-comedy, with the emphasis on comedy. But it's not a very funny movie either, as far as knee-slapping jokes are concerned.

The humor in the movie doesn't come from gags, but rather from the arch absurdity of the characters and their deeply stupid world, which they all take quite seriously. Look at the characters' names, all just this side of believable, the logical creations of the most pretentious people on Earth. Morf Vandewalt, Rhodora Haze, Jon Dondon, the P.I. Ray Ruskinspear, and of course, Vetril Dease, a chewy mouthful of a name that just screams "anagram," even though it probably isn't one. (Reshufflings of the name include "devil see art," "art: vile seed," and other frustrating combinations that almost seem like they make sense. Pretty good metaphor for the movie, honestly.)

The key to getting on Velvet Buzzsaw's level is understanding that the movie isn't the kind of horror that affects you with tragic circumstances or cataclysmic misfortune. The baseline of the movie's world is already a total horror show, and the killings are catharsis. The movie is, above all, a satire about bad people. When these characters get got, you're supposed to be amused.

Death of the author

Some of the first lines of dialogue in Velvet Buzzsaw come from a mechanized artwork called Hoboman, a mixed-media piece on display at Art Basel. Jake Gyllenhaal's critic character, Morf Vandewalt, has arrived to size up the piece, as well as whatever else catches his eye at the show. As he watches, the robot asks the crowd, "Have you ever felt invisible?"

In the piece, the comment appears to be about a homeless person, but it also applies to Velvet Buzzsaw's conception of the artist, and the grudge that drives the movie's story along. For a movie about the art world, very few artists appear — most of the characters we follow are just there to buy and sell. The artists themselves are spoken of like brand names, with their work praised for its popularity and monetary value above all else. They're not treated like people who put their hearts and souls into their work — especially the artist at the center of the plot.

Morf's role

Morf determines the value of art by filtering it all through his own perspective. What he doesn't like, doesn't sell. He may not be a gallery owner or an outright sellout like Rhodora, but he's still a gatekeeper, and a crucial part of the parasitic art world ecosystem. When Morf walks into the show, he passes by a sign that reads "There's no confusion in my house" — a statement that reflects his status as a critic. Confusion only exists in Morf's personal life. When he's at work, he speaks with exacting certainty.

Most people approach art exhibits with open minds and wonder, but not Morf — he's there to pass judgment. In his world, it's up to him to determine what qualifies as quality art. He dismisses the hit of the show, Hoboman, as a derivative work that doesn't impress him. His assessment effectively cancels out all other praise, sending the piece to languish in storage. His critiques have immediate consequences, with some bad reviews apparently being so distressing that they basically threaten artists' lives — like one creator who, Morf is told, gets drunk and crashes his car after being emotionally crushed by a bad review.

In real life, critics are just people doing their jobs, usually with nothing personal about it. In the world of Velvet Buzzsaw, Morf's critiques are presented as a kind of violence, justifying his own eventual death at the hands of the living Hoboman.

Dease: Nuts

Velvet Buzzsaw positions itself as a critique of the commercialization of art, with the vengeful spirit of Vetril Dease serving as the message's main vessel. But it's important to remember that Dease himself was not a particularly good person. As Morf and the other characters eventually discover, Dease in real life was very bad, violent, and emotionally disturbed. Death didn't turn him into a killer spirit — it really just let his dark soul loose on the world.

Despite all of this, it seems that everything would have been fine — nothing would have happened, and nobody would have died — if Josephina had just followed Dease's wishes and allowed his work to be destroyed. In real life, blaming the victim is a nasty thing. In the context of Velvet Buzzsaw, in which the victims are pretty much exclusively operating out of their own self-interest, it feels pretty justified. The killer is a bad person, sure — but there are no innocent victims in this movie.

People start dying

As haunting as Dease's paintings appear, it's not necessarily his artwork that's carrying a curse. Sure, his actual blood may be all mixed up with the paint he used, but that's more a signpost for one of the movie's themes — as well as a silly, self-indulgent thing that plenty of real artists do.

The actual function of Dease's curse (or whatever you want to call it) is to weaponize all art — not just his own paintings. This is why Hoboman comes to life to attack Morf, why Sphere is able to cut Gretchen's arm off in the movie's best kill, and why Josephina gets literally consumed by a roomful of living paint. The movie doesn't explain its rules very well, but the unifying thread of all the deaths is that they're committed by works of art — and with these characters being so steeped in the art world, they're always vulnerable. They do not appreciate the power that surrounds them, and all end up paying for their ignorance with their lives.

The velvet buzzsaw

Morf spends most of the movie getting increasingly suspicious about the many deaths happening around him, but the only character to entirely figure out what's going on is Rhodora. After Bryson, Jon, Gretchen, Josephina, and Morf all die, Rhodora accepts that the insane scenario of "Dease bringing art to life to kill people" probably has some merit to it.

Wisely sensing that she's probably next on the chopping block, she hires a team of movers to strip her home of all artwork — "Every image, every drawing, every postcard" — everything, counting up to 47 pieces in total. Satisfied that the job is done, she starts to rest more easily — until she feels a little tickle on the back of her neck. Taking the movie out on its most absurd note yet, Rhodora's "Velvet Buzzsaw" band logo from her days as a punk musician grinds to life and cuts her open.

At the beginning of the movie, Rhodora's old band is implied by the artist Damrish to have started from a sincere place before curdling into self-parody, presumably becoming more of a commercial engine and a brand name than a purely artistic outlet. Damrish, being only six months removed from a life of poverty, is still in tune with his creative roots, and acutely sensitive to the idea of selling out — a path Rhodora committed to for the sake of getting rich. It's a decision that ultimately dooms her, guiding her directly, over the years, to a most unexpected death.

Art for art's sake

There's a moment at the beginning of the movie when John Malkovich's character, the artist Piers, expresses a desire to get away from the B.S. of art as business and back to something pure. As he tells the gallery owner Jon Dondon, "I am fighting to get back to creation, to revelation, the billion years of energy sparking through our brain." As the movie eventually concludes, this path is a righteous one.

Writer-director Dan Gilroy talked about the themes Velvet Buzzsaw explores in an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, saying, "I was very interested in the idea of the relationship between art and commerce in today's world. It's a very uneasy relationship. [...] That's not to say that commercial success diminishes a work, but it doesn't define it, either. I wanted to get at the idea that art is more than a commodity."

Ultimately, the movie is about elevating the pure act of creation over crass commercialization. This is why the man on the street at the movie's end — a real hoboman — isn't in any danger from selling the Dease art he's found. Sold for cheap on the street, the art is judged on pure aesthetics, not by perceived value. Dease wanted his work destroyed, but at the end of the movie, it's out in the world anonymously, which also seems to be an acceptable fate. His body of work is no longer an eight-figure batch of commodities, but just pieces of art for art's sake.

Soul survivors

Velvet Buzzsaw expresses its themes not just through the people it kills, but also by the people it doesn't.

Poor Coco, who stumbles across so many of the movie's dead bodies, never gets a higher-level job that she so covets. Because of the distance she maintains from the art industry's rotten moral core, she survives Dease's wrath. Piers ducks out of all the performative pageantry of the art world and starts drinking again, surviving out of his desire to get away from the business' commercial side. Damrish, haunted by gazing into a Dease painting and feeling as though it's watching him, just gets up and leaves the movie at one point, sensing the danger and running for his life. These characters, the movie says, are all on the correct paths.

In the final shot of the movie, beneath the credits, Piers walks on a beach, scratching shapes in the sand with a stick. In close-up, it seems as though there could be some bigger message in what he's doing. But as the camera pans back and Piers keeps spinning, it becomes clear that there is no deeper meaning to his drawings. He's creating just for fun. His colleagues made art into something to consume, and were consumed by it. Piers goes back to basics, seeking that primal creative energy. He ends the movie looking drunk and joyful with his life intact, performing for no one in particular, drawing aimless circles on the beach.