Charlie And The Chocolate Factory Details That Only Adults Notice

Roald Dahl contributed many enduring classics to the canon of children's literature, including James and the Giant Peach, Matilda, and Fantastic Mr. Fox. His most popular work, however, will probably always be Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The story of Willy Wonka's wondrous candyland has been in constant publication since 1964 and has been adapted into a West End musical, an opera, some video games, a Tom and Jerry cartoon, and an album by Primus.

Towering above all of those, though, are two live-action feature films. Gene Wilder gave an unforgettable performance as the titular candy man in 1971's Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory from director Mel Stuart. In 2005, Tim Burton and Johnny Depp reimagined Charlie for a new generation. In short, countless children have encountered at least one version of Dahl's tale in their formative years.

As time goes by, those of us who grew up with the movies are bound to start noticing a few things that slipped by our younger selves. If you haven't traveled down that chocolate river yourself in a few years, you might be surprised by just how many sophisticated jokes, cultural peculiarities, and existential horrors await you. Grab your golden ticket and hold on tight for a tour of things only adults notice in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

One big candy commercial...

The classic Willy Wonka opens with a main title sequence examining the inner workings of a candy factory. While the credits roll by, vats of molten cocoa churn and intricate machines form flawless rows of chocolate chips. Kids, especially, could be forgiven for ignoring all the names on the screen in favor of ogling the sweets. An adult eye, though, might catch a pretty unusual copyright notice in the fine print, claiming ownership of the movie for "Wolper Pictures, Ltd. and the Quaker Oats Company."

How this classic film ended up getting produced by one company you've probably never heard of and another you know mainly from oatmeal is an interesting story. The studio system that had been in place since the dawn of Hollywood all but collapsed in the late '60s, clearing the way for small companies to get in the movie game for the first time ever. This provided an opening for Wolper Pictures, an ambitious group that had been working mostly in advertising and television.

Wolper's vice president, Mel Stuart, had been convinced by his daughter to try to make a film out of Dahl's book. At the same time, producer David L. Wolper happened to be in talks with Quaker Oats about providing an ad campaign for their upcoming foray into the candy market. The timing was perfect.

...that didn't really work

Quaker Oats agreed to finance the movie in exchange for the rights to produce any and all confections mentioned in it. They also stipulated that Charlie should be swapped out of the title for Willy Wonka in an effort to maximize brand recognition. Wolper and Quaker would share ownership of the finished picture and shop it around to major studios for distribution.

But here's another thing kids coming to the classic movie won't realize: it wasn't terribly successful. Upon its release in 1971, Willy Wonka was a financial disappointment, and while some critics were charmed, others called it "tedious" and "a terrible disappointment." As children began to discover the movie on TV and home video, however, its reputation improved until it was at last truly beloved.

The candy line had a rough road of its own. It turned out that Quaker Oats didn't really have a handle on the chocolate business, and they eventually sold off the brand and their share of the movie. The Wonka name was passed around through the decades to multiple companies churning out Gobstoppers, Runts, and Nerds. Nestle eventually found success producing Wonka treats, until finally retiring the brand, much to the disappointment of fans everywhere.

The economics of the factory

Speaking of financial failure, there's a major element of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory's story that goes entirely unmentioned, but is very noticeable to money-minded adults. It's present in every version of the story, though none of them address it directly. Charlie's family is poor, yes — it's a defining point of his character — but the question is, did Wonka make them that way?

Much of the wonder and mystique of the chocolate factory comes from its tragic closure years before the story begins, when Wonka had to lay off his workers due to corporate candy espionage. When it resumed operations, the gates remained locked and former employees were not invited to return. Did the shuttering of such a massive employer lead to the economic devastation of the town around it? The Burton film makes this an even more pressing question by introducing the notion that Grandpa Joe was one of the employees Wonka laid off. It's not much of a leap, then, to blame Wonka for the family's poverty.

The distribution of the tickets seems skewed

Another part of the story's set-up that's common to every version of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is the worldwide search for Wonka's golden tickets. We're told that the five lucky wrappers are being scattered "to all four corners of the Earth," and both movies have montages illustrating the Wonka craze taking hold on every continent. In fact, a major highlight of the 1971 film is the sequence of adults going to extreme measures to win the contest.

Isn't a little odd, then, that the five winners are all white kids from Europe and North America? Dahl never specified any particular origin or ethnicity for the children in his book, but both films made the same general casting decisions in this department. Of course, underwhelming representation is hardly a new or unique issue, but it does seem particularly galling that two movies about a worldwide contest both ended up so Euro-centric. It should be noted, also, that the book has had its own complicated history with race.

The sins of the children are wildly uneven

The main narrative thrust of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory comes down to naughty children getting punished while sweet, selfless Charlie Bucket is rewarded. That's all well and good, but a discerning adult might take issue with the harshness faced by some of the factory's victims. Augustus Gloop is definitely the victim of some unfortunate fat-shaming, but at least gluttony does qualify as one of the Seven Deadly Sins. And then there's Veruca Salt, whose spoiled rotten demeanor is certainly worthy of scorn.

But is Violet Beauregard really that bad? Her defining character flaw is that she chews a lot of gum. Each take on the story seems to add on a different negative trait — Dahl depicts Violet as somewhat dim, the 1971 movie makes her loud and obnoxious, and the 2005 version gives her excessive ambition. At any rate, she's pretty harmless. Meanwhile, there's a certain "Old Man Yells at Cloud" quality to Dahl's judgment of Mike Teavee's television watching... particularly from a man who sometimes worked in TV himself.

Willy Wonka cannot be trusted

Kids know that there's something off about Willy Wonka — his unpredictability is key in every incarnation of the character. Adults, though, will be quicker to pick up on the psychological tension and existential dread surrounding him, particularly in Gene Wilder's performance. Johnny Depp brings his own sense of awkward disquiet to Wonka, but Wilder is truly a nightmare, and that's by design.

Wonka's memorable entrance to the 1971 movie has him hobbling feebly out of the factory with the help of his cane, leaving a crowd shocked by his seemingly weakened state. It's only then that he drops into a graceful somersault and presents his true sprightly self to his adoring fans. This was Wilder's idea, and he felt so strongly about it that he would only take the part if he could do it. "From that time on," he explained, "no one will know if I'm lying or telling the truth."

It works. To kids, Willy is dazzling and slightly dangerous, but to adults who know manipulation when they see it, he's a straight-up horror villain. He spends the rest of the movie gaslighting his charges at every turn, exposing them to nightmarish experiences like that boat ride and then pretending none of it ever happened. The '71 version is also the one where we never see the punished children alive at the end. We only have Wonka's word that they're okay, and we know we can't trust that.

The adult jokes

Roald Dahl is most definitely best known for his children's books, but he was also very prolific in more adult genres of literature. Whatever his intended audience, he never condescended to his reader. Open to any page in any given Dahl book, and you're sure to find a sophisticated reference, a cathartic bit of violence, or maybe even an off-color joke or two. Charlie was no exception, and the movies followed suit.

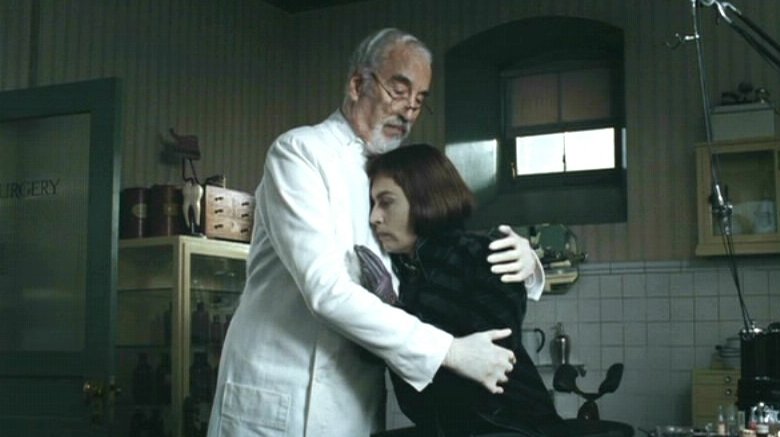

Take, for instance, the "musical lock" on the door to the grand Chocolate Room. Wonka plays a few bars from Mozart's Marriage of Figaro, which Mrs. Teavee incorrectly identifies as a Rachmaninoff piece. It's played for laughs, but only the most prodigious musical prodigy in an audience of kids (or adults, for that matter) will get it. There's also the scene parodying overwrought soap operas in which kidnappers are demanding a woman's stash of Wonka bars as ransom for her husband.

And who could forget the snozberries? Do you actually know what a snozberry is? Yes, it's dirty.

The factory is a terrible prize

So, Wonka rewards Charlie with the entire factory. He's going to own and operate the whole thing, and Charlie is all too eager to accept his prize. And why wouldn't he be? Having your own candy factory sounds like a dream come true for any kid, right? From an adult perspective, though, it seems more like Charlie's just been saddled with a job he is in no way prepared for.

Sure, the factory is a magical place — there's a chocolate river, miraculous machines, and an edible wonderland of delights. But it's also been proven to be susceptible to real-world concerns like layoffs and cutthroat competition. The Bucket family's dire need for food and shelter will be solved, of course, but this poor kid has essentially just been named CEO of a major multinational corporation. No quantity of gumdrops or Gobstoppers will help with the pressures of that kind of career.

The movies pad out their themes

Roald Dahl's Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is a very simple morality tale, in which children are either rewarded or punished for their cartoonish levels of goodness or badness. There's nothing wrong with that — kids sometimes need clear, easy-to-understand lessons and Dahl never failed to spice up even the most basic plots with his trademark wit and flair. Movies, on the other hand, tend to feel a need to be about something, and the two Chocolate Factory adaptations are fascinating examples of this translational struggle.

The 1971 movie gives Charlie an opportunity to prove his goodness by facing temptation. The subplot in which Wonka's competitor Slugworth (who is mentioned only briefly in the book) offers Charlie a fortune in exchange for a stolen Gobstopper prototype was entirely fabricated by the filmmakers. They also added the "fizzy lifting drinks" scene, in which Charlie and Grandpa Joe break the rules and nearly lose the grand contest. This movie's Charlie is more complex than the hero of the book, a kid who's as imperfect as any other, but who's trying his best.

The 2005 movie shifts the main character arc to Wonka himself, inserting several flashbacks revealing his troubled relationship with his father. None of this has any relation to the book, but it does fit with the father-son themes common to Tim Burton's work. Here, Charlie is the one who teaches Wonka a lesson, as the dedicated candy connoisseur comes to realize the value of family.

Why no sequel?

Roald Dahl wrote not one, but two books detailing the adventures of Charlie Bucket and Willy Wonka (he actually started a third, but never finished it). Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator was published in 1972, picking up right where the first book left off and sending the characters on an adventure in outer space. It may not be as beloved as its predecessor, but maybe that's just because it's never been made into a hit movie.

Dahl was very unsatisfied with Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory's finished product (despite receiving a solo screenwriting credit, he failed to meet deadlines and his script was largely rewritten). Among his complaints were the songs, the casting of Wilder, and a perceived overemphasis on the character of Wonka (a bit of an odd complaint, considering he doesn't even appear until 40 minutes into the movie). He was so displeased that he refused to sell the movie rights to Glass Elevator for as long as he lived.

But since when has Hollywood let a little thing like the wishes of the dead stand in the way of a good franchise? Kids may be satisfied to watch these two movies over and over, but media-savvy adults have to wonder why our current climate of nostalgia hasn't brought us an adaptation of a sequel that's sitting right there on the shelf. Even stranger, there is a Wonka movie in the works... but it's a prequel.