The Dark Side Of These '80s Sitcoms

The 1980s were a golden age of sickeningly sweet, condescending, and cloying family sitcoms. They told us when to laugh (at broad comical antics, like babies saying "dude") and how (the braying laugh track), as well as when to feel (when the slow piano music kicked in). And in spite of all that, they sure were fantastic. Most Americans over a certain age have fond memories of devouring these so-called comedies in their youth, and look back through a gauze of nostalgia on landmarks of Reagan-era pop culture like Who's the Boss?, Family Ties, Growing Pains, and Full House. They were shows for families and about families. Truly, these were innocent shows for innocent people in innocent times.

Or...maybe not. Looking back on those old shows with a mature (some might say cynical) viewpoint reveals a lot of layers and quirks that we just didn't notice when we were kids. Mostly, there's an undercurrent of darkness and sadness to all of those sugary family stories of yesteryear. If you're ready to have your childhood ruined, take a journey with us into the dark side of your favorite '80s sitcoms.

An almost Full House

Full House might be the definitive '80s family sitcom by which all other family sitcoms are judged. After all, its fans' nostalgia was strong enough to revive the show for the 21st Century. Nearly every episode followed the same trajectory — one of the three Tanner kids (D.J., Stephanie, or baby Michelle) makes a bad decision, gets caught, and their dad, Danny, gives them a patronizing lecture and a light punishment. Also, the child in question says something to the effect of, "Gee, Dad, I never thought of it that way." Then they hug, the audience goes "awwww," and the credits roll over footage of the Golden Gate bridge.

Those Tanner kids do dumb stuff all the time, but let's give them a break. Those three girls endured a horrific childhood trauma — their mother died in a car accident. That can lead to dark, long-lasting psychological ramifications...as would their abrupt, forced change of living situation. Sure, they've got Uncles Jesse and Joey in the house to raise them with kindness and love, but that's even more sudden change for a still-developing mind to process. The darkness doesn't end on the screen, either — there's been no shortage of turbulence and controversy for the cast over the years.

The Cosby Show exhibited some red flags

The Cosby Show was a monster hit in the 1980s, credited with revitalizing not only the sitcom format, but a struggling NBC. Legendary comedian Bill Cosby helped develop the show himself, carefully considering every element for the message it sent viewers. For example, Cosby rejected an early idea to make his character a limo driver — he made Cliff Huxtable a doctor instead, to provide an example of a professional African-American man on television.

But viewed through the eyes of more recent events, the details associated with Cliff Huxtable's career as a physician become creepy...if not alarming and somewhat sickening. Of all the specialties Cosby — sent to prison in 2018 for sexual assault — could have chosen for his character, he went with obstetrician/gynecologist. That means the man accused by multiple women of slipping them drugs for the purpose of assault was cool with playing a guy with access to prescription drugs who treats only female patients (and in his weird, isolated basement home office to boot).

Orphans were very big in the '80s

Within the broader world of saccharine 1980s family sitcoms, a bizarre, well-populated sub-genre developed: comedies about the oh-so-hilarious subject of orphans. Perhaps propelled by the enduring popularity of the musical Annie or Anne of Green Gables, there were many shows in the '80s about kids who are awfully plucky despite their parents being dead.

On Diff'rent Strokes, Gary Coleman and Todd Bridges played Arnold and Willis Jackson, respectively, two African-American children lifted up out of their sad, parentless existence in Harlem by a kindly white millionaire (Conrad Bain) who takes them to live in his deluxe apartment in the sky. Diff'rent Strokes never commented much on the trauma or racial/class issues that would frame this kind of situation in real life. Neither did the Diff'rent Strokes clone Webster, which starred Emmanuel Lewis as the orphaned child of a football player who goes to live with his biological dad's best friend (Alex Karras) and his wife (Susan Clark).

But Punky Brewster might be the saddest orphan-com of all. That Soleil Moon Frye vehicle was about a sad and lonely old man (George Gaynes) who takes in the titular orphan. You see, Punky's father took off, and then her mom abandoned her in a mall with little more than two mismatched shoes and a dog named Brandon.

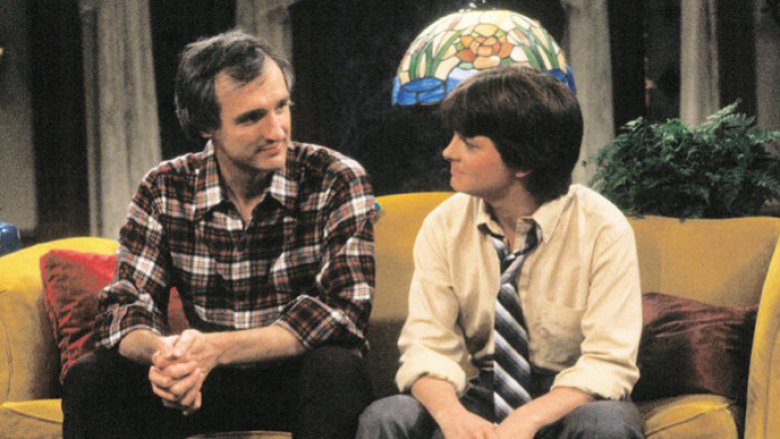

Family Ties and what can break them

Family Ties hit TV in 1982 with a clever premise that tapped into a cultural zeitgeist of the time. The "flower children" of the late 1960s — hippies, Baby Boomers, the countercultural youth — were well into adulthood by the early '80s and settling into the mainstream lives they'd once railed against. On Family Ties, Michael and Elyse Keaton had been hippies, but now lived in Ohio with their three (eventually four) children. But they're still trying to change the system from within and make the world a better place through their work — he runs a public TV station and she's an architect.

A lot of the show's dramatic tension came from the Keaton parents' relationship with oldest child Alex P. Keaton (Michael J. Fox), a hardcore and stereotypical Young Republican and Ronald Reagan acolyte. He frequently makes jokes about cutting welfare and destroying the social safety net, quite at odds with his parents' liberal outlook. In fact, if Alex's passion for small government conservativism played out to its end, it would cut funding for his father's public television station. In other words, Alex P. Keaton actively works to destroy his own father's livelihood.

It's a big wonder why Small Wonder didn't put off audiences

Complex once named Small Wonder the fifth-unfunniest sitcom of all time. While it's definitely no Veep or even The Big Bang Theory, it's more notable for being weird...and skeevy. Small Wonder is about Ted Lawson, an engineer for a robotics corporation who develops a lifelike, humanoid robot, ostensibly to assist the differently abled with household chores. In order for the robot to learn how to behave in a real-world environment, he takes it home to live with him and his nuclear family.

That's a good idea with lots of potential, except it's hard to get past some things about the robot. It's downright creepy that of all the forms the robot could have taken, Ted Lawson chose to make his "the spiting image of a 10-year-old girl," and one he dresses in what's basically a maid outfit at that. Also, V.I.C.I. (that's the robot's name; pronounced "Vicky," it stands for "Voice Input Child Identicant") always speaks in a typical robotic monotone, which means everybody in the Lawsons' orbit should be able to tell V.I.C.I is an android. They can't, though, so they must all be idiots.

Don't drink to that

As the famous theme song suggests, Cheers on Cheers is a place "where everybody knows your name." Perhaps as a nod to this, the bar's best and most well-known customer is Norm Peterson, played by George Wendt. Other patrons and employees alike greet Peterson upon his daily arrival with an enthusiastic "NORM!" in most every episode, as he literally rushes into Cheers, hustling to his favorite barstool with great quickness so he can get to the business at hand as soon as possible: drinking lots and lots of beer.

Norm is a regular at the bar, and Wendt is a regular on Cheers, one of just a few members of the iconic cast whose presence at the watering hole isn't because they're playing someone who works there. In other words, Norm Peterson is probably an alcoholic. All he ever does is drink, and he drinks so much that in the show's 1982-1993 run, viewers never get to meet his wife, Vera. He only goes home when he has absolutely has to, and she never comes in to Cheers because she doesn't want to see her husband drink himself under the table.

Growing Pains almost killed Tracey Gold

Anorexia wasn't a widely known condition until the 1980s — the 1983 death of singer Karen Carpenter was a result of her struggle with the eating disorder, which increased public awareness and knowledge. But culture changes slowly, so Growing Pains laid on the "fat jokes" pretty thick throughout its 1985 to 1992 run. Scripts for the family sitcom frequently featured Seaver brothers Mike (Kirk Cameron) or Ben (Jeremy Miller) making quips about the physical appearance of their sister, Carol (Tracey Gold), commenting on her supposedly widening figure or large rear-end. There's also a 1988 episode where Carol experiences an extended nightmare sequence where she's very overweight.

Little did writers know that in real life, Gold was fighting a years-long battle with anorexia. By the end of the show's seventh season in 1992, Gold's weight plunged to a dangerous 80 pounds. She missed some episodes because producers ordered her into an in-patient treatment program for her disease. She returned for the series finale, but had to struggle through the closing dinner scene by pretending to eat.

My Two Dads are complete strangers

My Two Dads was pretty edgy for a family sitcom from 1987. One part The Odd Couple, one part Punky Brewster, it was about two adult men who had nothing in common and who held completely different approaches to life (Joey was chill; Michael was straight-laced, of course) who decide to live under one roof to raise a motherless teen named Nicole (Staci Keanan). She happens to be the daughter of a deceased woman who dated — and slept with — both Joey (Greg Evigan) and Michael (Paul Reiser) around the same time. That means Nicole is the biological daughter of one of them, but it's never revealed who, and instead the three form a nontraditional family and have wacky domestic adventures for three seasons.

But let's rewind to the show's setup. It's a comedy show, geared at children, predicated on the notion of a dead mom. Her daughter, in mourning and seemingly alone in the world, is forced (by a judge) to live with strangers, one of whom is her biological father that she's never met. And from the beginning of the show, Nicole is also well aware of her mother's scandalous (for 1987) "dating around" lifestyle. That's a lot for a kid to deal with.

Too Close for Comfort is too problematic for repeats

Too Close for Comfort wouldn't work today, because the notion of somebody doing their job from home isn't as novel as it was when this show first aired in the early 1980s. Another roadblock: some of its decidedly less-than-woke plot lines.

The great Ted Knight (Ted Baxter on The Mary Tyler Moore Show) played Henry Rush, an uptight cartoonist. Here's where the sitcom hijinks factor in: he can barely get a moment's peace to draw Cosmic Cow because he works from home. In Rush's case, home is a San Francisco townhouse where he's constantly interrupted by his wife, two grown daughters, and Monroe (Jim J. Bullock), the fussy and nerdy friend of one of the daughters.

At the start of the series in 1980, Rush's downstairs tenant is a guy named Rafkin, who Rush thinks has a lot of female visitors...until he dies, and Rush realizes that all those women were Rafkin cross-dressing. And then there's the 1985 episode "For Every Man, There's Two Women." The plot: two obese women kidnap Monroe and sexually assault him in their van. It's played for laughs.

Night Court is full of unseemly individuals (and the specter of death)

Night Court aired at 9:30 p.m. in most areas, so NBC wasn't looking to attract kids. Still, there was plenty of stuff on the show for kids to enjoy, including Judge Harry Stone's (Harry Anderson) bubbly demeanor and penchant for magic tricks, not to mention bailiff Bull's (Richard Moll) funny voice and puppet doppelgänger. But really, Night Court was about a night court, a New York City late-hours courtroom set up to process criminals, primarily prostitutes, pimps, drug offenders, and street thugs. While those elements can be frightening and dangerous in real life, on Night Court, they're just part of the parade of criminals with whom Judge Stone exchanges witty wisecracks as he pushes them through the criminal justice system.

One other weird thing about Night Court: It might have been cursed. In seasons one and two, Selma Diamond played a sassy bailiff also named Selma...until she died of cancer. The show replaced her with Florence Halop as a bailiff named Florence. And then she died, too. The third and final female bailiff, Roz, was played by Marsha Warfield—who, unlike the sixtysomething Diamond and Halsop—was more safely ensconced in her thirties.