The Brian O'Conner Decision In Fast X That Creates One Big Plot Hole

Contains spoilers for "Fast X."

Nobody likes the guy that points out plot holes while you're walking out of the theater. More often than not, pointing out these moments either betrays a misunderstanding of some aspect of the story or an unwillingness to engage with the film on anything other than a literal level. However, there are some, rare instances in which plot holes do genuinely undermine the ability to enjoy a film's story — such is the case in "Fast X."

The Fast Saga has never been known for its airtight logic — in fact, they're seemingly aware of how absurd these movies have become and are flaunting it as a marketing strategy. But when this lack of logic is used to lazily justify a distracting, convoluted subplot that exists only to extend and overstuff a movie already blatantly gluttonous, these "plot holes" reveal the true enemy of enjoyable stories: thoughtlessness.

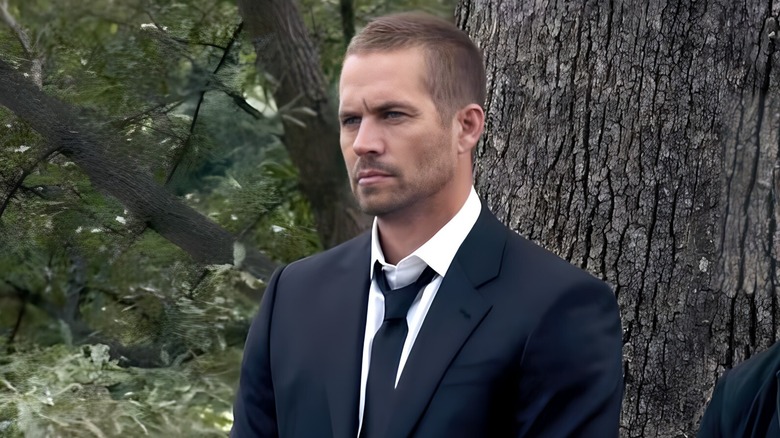

Throughout the film, one of the storylines the audience follows is Jakob Toretto's (John Cena) quest to get Little Brian Marcos to safety. The parameters of the mission are vague, even by "Fast and Furious" standards, and things get even more confusing when a character reveals that Brian O'Connor — the former franchise lead played by the late Paul Walker — is somehow entirely safe from harm with his own family.

Why wouldn't Jakob and Dom's son be safe with Brian's family?

What makes this story choice frustrating is that it's such an unimaginative solution to an obvious problem that creates more questions than it answers. While it's understandable why "Fast X" would want to address his character in some way, simply not mentioning Brian at all would arguably be preferable to this. If it was a matter of involving their late co-star in the story somehow, there were surely more meaningful ways to do so; if it was a matter of filling the potential plot hole of why Dante Reyes (Jason Mamoa) wouldn't go after Brian's family, the film is underestimating its audience.

The characters seem so positive that Brian's family is safe that they don't even question or worry about it for more than two lines, which both makes for a fleeting tribute and immediately begs the question of why Dom's family doesn't join him at this supposed impenetrable safe house.

"Fast X" is by no means abominably long in terms of runtime, yet it somehow manages to feel arduous in comparison to this year's other bombastic action blockbuster, "John Wick: Chapter 4" — probably because of decisions like these, which create plotlines that don't attempt to engage the audience beyond the surface level.

Fast X is just creating plots to fill time, not story

On paper, the premise of Dominic Toretto (Vin Diesel) confronting a ghost from his past whom he orphaned and bankrupted is ripe with dramatic potential and is precisely the sort of story that fits this franchise like a tailor-made glove. It has themes of family, loss, and past sins — all things that make for a great "Fast" adventure, but with the opportunity for a more complicated emotional narrative.

A narrative like that, however, takes time to fill — time this script excitedly affords to three thematically unrelated subplots that serve only as flimsy vehicles to keep the sprawling ensemble involved. For a contrasting example, consider "Avengers: Infinity War" (a film that clearly served as inspiration for this installment in all the wrong ways).

The superhero epic has about as many simultaneous plots as "Fast X," but they're all unified under a clear controlling idea, which is a term Robert McKee coined in his screenwriting bible "Story" that refers to a central, binding thematic statement that can help unify the events of a story. Every scene in "Infinity War" feels important because they all ask the audience to psychologically engage with the controlling idea that sacrifice is necessary for survival.

There's no real controlling idea in "Fast X" — certainly not one that unifies its four plotlines. The reality in which they exist as shallow explosion fodder is hard enough to stomach for two hours as it is — presenting the audience with possible reasons why they shouldn't exist in the first place just adds insult to injury.