What Tetris Doesn't Tell You About The True Story

While movie fans often cite "Rocky IV" as the movie that brought an end to the Cold War in Hollywood, gamers look to "Tetris" as the title that helped bring down the Iron Curtain. It was created by a Russian computer programmer named Alexey Pajitnov during his spare time, and little did he know it would spark a battle that would change the face of video games forever. But to make its way out of Soviet Russia would take more than just a daring escape from a totalitarian regime; it took the efforts of video game executives like Henk Rogers, who showed no fear in fighting to bring the game to the Western world.

Which is where the Apple TV+ production based on the saga of Rogers comes in, depicting an unbelievable journey to secure those rights to the little-known Soviet puzzle game. Taron Egerton stars as Rogers, who makes a deal with Nintendo to bring the game to their first handheld gaming device, the Game Boy, but in the midst of the Cold War must first travel to Russia and deal with the state-run officials who control the game's fate.

Full of stirring drama and captivating suspense, "Tetris" gives audiences a look at the story behind a video game phenomenon. But it doesn't tell the whole story. So press start and choose your theme music, because here's how the blocks really fell.

The origin of Tetris

In the "Tetris" film, viewers are told that Russian programmer Alexey Pajitnov (Nikita Efremov) invented the game on a primitive computer. But there is so much more to the story of the man responsible for one of the most popular video games of all time, and how it came to be. While in the film it seems like Pajitnov was working for the trade bureau Elorg, he was actually employed by the Russian Academy of Sciences, a think tank consisting of scientists, writers, and philosophers who were often given far more freedom than most in their field.

In the mid 1980s, Pajitnov was at the Academy working on early efforts into developing artificial intelligence. Always obsessed with games and puzzles, Alexey had a passion for computer game design, and often used the availability of new hardware as an excuse to dabble in programming his own puzzles. When it comes to the "Tetris" game, Alexey was heavily inspired by a game from his youth called Pentominoes: A more generic block game consisting of different shapes, all constructed out of five squares that could be rearranged to make a solid rectangle. One look at the game and it's hard to not recognize it as the spiritual predecessor to "Tetris" and an inspiration for Alexey's digital masterpiece.

Alexey's first attempt was essentially a computer translation of Pentominoes, but he soon landed on the idea of falling game pieces that could be rotated. But it still needed one more trick, and with the addition of rows that would disappear when completed, "Tetris" was born.

The arrival of Tetris in the West

When "Tetris" came to the Nintendo and Game Boy in the 1980s it became an instant classic, launching on a journey to become one of the most beloved puzzle games of all time. But that certainly wasn't the first time anyone had played the game outside of the Soviet Union; while the film mostly darts past that part of its history, the real story of "Tetris'" arrival in the West is an interesting one in its own right.

As is briefly mentioned in the film, the rights to the game on computers had been acquired by Robert Stein and licensed to Mirrorsoft — a key player in the United Kingdom — in the mid '80s. They successfully launched the game in their home territory for computers, but they weren't its only manufacturer, something the movie never mentions. In fact, "Tetris" wound up being released in the United States by Mirrorsoft subsidiary Spectrum HoloByte, who acquired the U.S. computer rights from Stein; it wound up being quite a success, selling more than 100,000 copies.

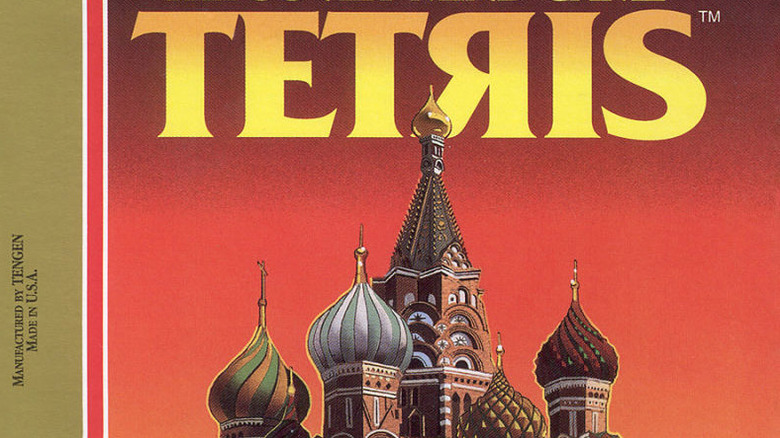

To market the game, Spectrum Holobyte decided to embrace its Russian roots, with the box art using Cyrillic text and featuring images of St. Basil's Cathedral. Enticing gamers with a peak behind the Iron Curtain, the game was a glimpse at a distant world that many in the West had never seen.

How Henk Rogers discovered Tetris

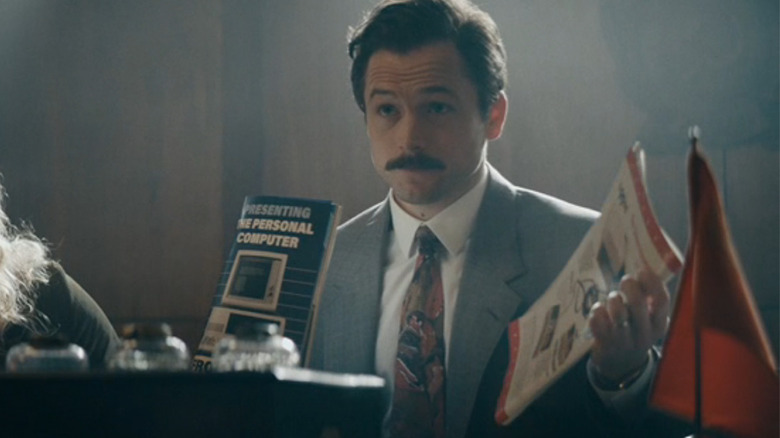

The film opens with Henk Rogers attending an electronics expo and trade show, unsuccessfully hawking his own game, a video game version of the classic Chinese board game called "Go." While there, he is lured over to another booth that is showing off "Tetris" when his hired helper is distracted by the game herself, and he is visibly annoyed that she wants him to try a competitor's game.

While it is true that Rogers developed a title for Nintendo based on "Go," what the movie doesn't tell you is that Rogers primarily made a living in those days looking for titles to import to Japan. Far from being reluctant to try "Tetris," such a discovery would be exactly why he went to such shows in the first place.

As Henk himself has described it, he spotted "Tetris" at the 1988 Winter Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, where Mirrorsoft subsidiary Spectrum HoloByte was showing off their Russian puzzle game. "Tetris was probably the quietest game at the show," Rogers explained years later. "Even then, products were graphically exciting, but this game was a totally different thing. I wanted to play it because it struck some basic chord. I couldn't stop playing." As legend has it, Rogers was so entranced that he got back in line to play the game over and over, and was convinced that the game was precisely what the Japanese market was craving.

Henk's Russian translator

Apple TV's "Tetris" is a dramatic reenactment of Henk Rogers' sojourn to Soviet Russia and his harrowing negotiations for the Japanese rights to "Tetris." It's revealed at the film's climax that the young woman named Sasha (Sofya Lebedeva) who he randomly picked out of a crowd to serve as his translator is actually an undercover KGB operative. It's a shocking reveal meant to throw the audience for a loop, but it might surprise viewers to learn that in reality, Rogers did actually hire an interpreter who turned out to be a KGB agent. Unlike the film, though, it was no secret.

In the real story of Henk Rogers' trip to Russia, the woman he hired was named Ola, and he was well aware that she was a government agent when he hired her. As Rogers wrote in an editorial for the Guardian in 2014, he picked her from a group of people in the lobby of his hotel just like in the film. "They were all KGB," Rogers wrote, seemingly very much in-the-know that he was surrounded by agents of the state. "But [Ola] was beautiful and very perky, when everybody else was doom and gloom."

Like in the film, Ola took Rogers to Elorg, but from there, the story diverges; according to Rogers, Ola refused to enter the building with him, and her part in his negotiations ended there. The notion that she worked with Elorg to intimidate him, or was involved in a sinister government plot, was fabricated for the film.

Tetris on Game Boy

Set mostly in 1988, the Apple TV+ film "Tetris" sees Henk Rogers attempting to secure the rights to produce the game for the Nintendo Entertainment System in Japan. Early on, however, he is told by Nintendo's CEO to visit their subsidiary in Seattle, Washington, where he discovers their American team working on a prototype for what would become the Game Boy. Company lawyer Howard Lincoln (Ben Miles) introduces him to the portable game system, and tells him they're planning on releasing it with a handheld version of their biggest franchise, "Super Mario Land."

Believing that "Tetris" will help sell the new system to a broader audience, Henk suggests that the Game Boy be packaged with the Russian puzzle game instead. Lincoln is instantly receptive, but needs the handheld rights to the title, which kicks off the dramatic plot that sends Rogers to Russia. While the broad strokes may be true, the truth is that Nintendo always hoped to launch the Game Boy with "Tetris." It wasn't Henk Rogers' idea at all, it was Nintendo who approached him with the idea of packaging "Tetris" with their new handheld system.

As recounted in the 2004 documentary "Tetris: From Russia with Love," Lincoln already had a pre-loaded version of the game on the Game Boy when the device was first shown to Rogers. It was then that the intrepid licenser knew he had to get them the rights they needed to make it a reality.

Why Henk Rogers went to Moscow

In a dramatic, revealing moment in Apple TV's "Tetris" film, Rogers flies to England to confront Mirrorsoft about the handheld rights to "Tetris." He seemingly does this to see their reactions to the request in person, to judge whether the rights are readily available, as he does not want to disclose the existence of Nintendo's Game Boy prototype. As it happens, Mirrorsoft's license intermediary Robert Stein is there, and his demeanor suggests to Rogers that nobody has the handheld rights, and he plans to fly to Moscow to get them himself.

There is more to this part of the story, though, and the truth isn't quite as dramatic. As revealed in the 2004 documentary, Rogers actually approached Stein himself asking for the deal-maker to go to Moscow to help secure him the handheld rights to "Tetris." Stein wasn't an employee of Mirrorsoft, and was negotiating on behalf of multiple clients, so this wasn't out of the ordinary. But Rogers became nervous with the slowness of Stein's movement on his request. "We were exchanging faxes on a weekly basis for three months, and then I started getting nervous because it just seemed to be taking so long," Rogers explained. "He said he was going to go to Russia, he kept on saying that, and he wasn't going, so I became really suspicious."

The truth of the matter, though, is that Stein was already working on handheld rights for Mirrorsoft. This prompted Rogers to hop on a plane to secure the rights on his own.

Helping the Russians

In one pivotal scene in the "Tetris" film, Henk Rogers helps Nikolai Belikov understand how Mirrorsoft was able to acquire video game rights to the game without realizing it. He points out that the term "computer" is never explicitly defined, and gives him advice on how to ensure the mistake doesn't happen again. But according to the real-life Henk Rogers, his involvement in restructuring contracts for Belikov and Elorg was more far-reaching than simply helping him define computer. To get the rights he was looking for, he knew he had to be forthright and helpful, so that's exactly what he did.

"I was very open with the Russians and they decided to give me console rights," he told the Guardian in 2014. Part of that openness meant drafting a contract that was favorable to both sides, as Rogers eschewed negotiating tactics he might have tried if back in his native country. "I gave them the best contract I've ever seen in the industry – clear, concise, no bull**** – partly because there wasn't time for any renegotiations." Not only was the new contract helpful to Rogers getting the rights he needed, it was also helpful to Belikov and Elorg, who had only limited experience in capitalist deal-making.

"Elorg used it as the template for all their other deals," Rogers claims. This didn't sit well with his competitors, who had apparently been using Elorg's negotiating inexperience to their advantage. "The Maxwells were furious."

Complicated negotiations between rival powers

Some of the most intense moments in the film version of the story involve Nikolai Belikov's attempts to outwit his three Western rivals: Henk Rogers (Egerton), Robert Stein (Toby Jones), and Kevin Maxwell (Anthony Boyle), who were all in Moscow competing to get the rights. Belikov repeatedly pits the three parties against each other, keeping them separated, and using information from them to squeeze out a better deal; this is at least partly true, as revealed in the 2004 documentary. But the film portrays Belikov as a mostly-naive official who has no idea who Henk Rogers is or what he wants, while in truth, Belikov was alerted to his arrival by government agents.

Similarly, the movie includes a corrupt KGB agent (Igor Grabuzov) who blackmails Mirrorsoft's owner and forces Belikov to sign the rights away to the Maxwells. This leads to a complicated scheme where Alexey must send a covert fax to Rogers to help him steal back the rights. The real-life negotiations weren't quite as dramatic.

While it is true that the Maxwells tried to exert pressure on Belikov by calling in favors from Mikhail Gorbachev (Robert Maxwell was friendly with the Soviet Premier), in reality there was no nefarious KGB blackmail scheme — Belikov favored Rogers because of the man's honesty. Alexey Pajitnov, meanwhile, actually played a larger role in the deal than the movie suggests, and pushed for Belikov to give the rights to Henk Rogers.

Shigeru Miyamoto had a say

In the film, Henk Rogers first visits Nintendo in Japan to sell them on the idea of bringing "Tetris" to the far East; CEO Hiroshi Yamauchi (Togo Igawa) is enthusiastic after playing the game for himself in his office. After a quick negotiation, he offers Rogers a massive cash advance to allow him to secure the rights and become an official Nintendo licensee. But that doesn't quite tell the whole story, and it may surprise longtime video game fans to learn that legendary game designer Shigeru Miyamoto actually had a small part to play in the story of "Tetris."

Detailed in "The Story of Tetris" from Gaming Historian, Yamauchi was less gung-ho than the movie makes it seem, but did have passing interest in the game, and wanted a second opinion. He turned to the company's biggest creative force at the time, Miyamoto, the man responsible for creating "Super Mario Brothers," "The Legend of Zelda," "Star Fox" and more. Miyamoto gave his boss a thumbs up on "Tetris," and when asked why it was worth bringing to Nintendo, he said plainly, "because your secretaries and accountants are playing it."

Lawsuits from Atari

The major players in "Tetris" aren't gamers, but video game publishers, and that includes publishing giant Atari. But their involvement in the film keeps them largely in the background, a looming threat to the three main figures in the story. The real-life tale of how "Tetris" arrived in the West was a little more complex.

The movie gets most of the details right: Atari did snag the rights to consoles and arcade versions of "Tetris" for Japan. But according to "The Story of Tetris" from Gaming Historian, they were far more interested in making the game in the U.S. than in the far East, and Henk Rogers actually secured his deal for the Japanese territory before the mess with the Russians muddied the waters. But the real story that the movie leaves out is what happened in the aftermath of the events of the film. Because once contracts had been re-drawn after meetings in Moscow, it was Rogers and Nintendo who wound up with console rights. Nintendo immediately sent a cease and desist letter to Atari, who responded by launching a massive lawsuit against their competitor.

To settle the dispute, Elorg director Nikolai Belikov actually came to the United States and testified in the court case. The judgment was swift, and suddenly Atari found themselves without rights to "Tetris," and they were forced to pull thousands of copies from store shelves. To this day, the Atari version remains a valuable collector's item.

There were no dramatic chases

Those who have seen the "Tetris" film will likely agree that the most exciting moments are in the film's climax, which sees Rogers returning to Moscow for final negotiations for handheld rights. He brings with him two executives from Nintendo of America in Howard Lincoln (Miles) and Minoru Arakawa (Ken Yamamura). After convincing Belikov to go against KGB orders to do a deal with Mirrorsoft and the Maxwells, the trio of foreigners — now with signed paper in hand — must get out of the country before corrupt government operatives can get to them. This leads to a nail-biting car chase and a foot race through the Moscow airport, and it probably won't be a shocker to learn that much of this excitement was invented for the movie.

The truth is, Rogers did return to Moscow after Belikov was receiving pressure to sign the rights to the Maxwells, but it wasn't nearly as ominous as the movie made it seem. As mentioned, there was no KGB blackmail scheme, and as a result there was no one trying to have Rogers arrested. It's also implied that Rogers brings the pair of Nintendo executives along for the trip because he needs their deep pockets to sign the deal; in reality, it was Belikov who requested they come along, to help convince his contacts in the Russian government that working with Nintendo was simply the better deal.

The final score

Sure, every movie needs to end somewhere, and the "Tetris" film didn't need to spend another hour dramatizing what happened to the game and all the people involved after Nintendo nabbed the rights. But even with a handful of real-life photographs and a few brief updates during the credits, the film mostly glosses over what's happened to Henk and Alexey in the years since. Because after the launch of Game Boy, "Tetris" quickly became a cultural phenomenon that connected gamers across two hemispheres, and changed the fortunes of both men.

In the wake of the game's success, the Russian inventor of the game saw no profits, despite Elorg's financial windfalls from the deal. After the fall of the Soviet Union, he moved his family to the United States in 1991, and five years later he and Rogers started the Tetris Company. Finally able to see royalties himself on the sale of the game and associated merchandise after the original deals had expired, Pajitnov had his day. Not long afterwards, Pajitnov took a staff job at Microsoft as their first in-house game designer, where he has remained since.

As for Rogers, he's branched out into other industries, founding Blue Planet Energy, a company that specializes in renewable energy storage. He's also the founder and chairman of International Moonbase Alliance, which aims to create livable settlements on the moon and Mars.