The Ending Of Living Explained

What does it mean to be alive? "Living" ponders this question, handed down through the centuries not only by the human condition, but specifically three of the greatest authors of either cinema or literature. Inspired by the great Russian writer Leo Tolstoy's novella "The Death of Ivan Ilyich," Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa made "Ikiru," one of his best movies, in 1952. "Ikiru" has in turn been adapted into "Living," re-set in Britain instead of Japan and written by acclaimed Japanese-British novelist Kazuo Ishiguro.

The result, under the assured direction of South Africa's Oliver Hermanus, is a quiet and stately film that contains a profound and moving philosophical underpinning. All three stories — Tolstoy's, "Ikiru," and "Living" — are about a lifelong bureaucrat diagnosed with a terminal illness who re-evaluates what to do with the last bit of life they have left. No matter the era, the impossibility of the human condition remains the same: Tolstoy pioneered realist fiction that explored the gulf between humanity's inner psychology and outer lives in 19th-century Russia, Kurosawa the existential repression of post-WWII Japan, and Ishiguro's novels the quiet despair of 20th-century Japan and Britain.

In "Living," aided by an Oscar-nominated performance from Bill Nighy, Ishiguro and Hermanus achieve something deep, insightful, and deceptively simple with just a few elliptical cuts in time. Like "Ikiru" before it, the movie invites endless re-examination and unveils hidden depths. This is the ending of "Living" explained.

The timeline of Mr. Williams' last days

Although it isn't exactly "Pulp Fiction," "Living" doesn't tell its story in a linear fashion. We meet Mr. Williams (Bill Nighy) in July 1953, the same day that he receives a terminal cancer diagnosis, and then we experience the next few days with him as he processes the news. After an excursion to a local seaside resort town, he enjoys a pleasant lunch with his departing co-worker, Ms. Margaret Harris (Aimee Lou Wood). Through the sly use of a desktop calendar, "Living" jumps ahead to a few weeks later to August, when Mr. Williams and Ms. Harris bump into each other once again in Piccadilly.

From there, "Living" jumps ahead to after Mr. Williams has died. It's about six months later that we meet the characters again at Mr. Williams' funeral. The film tells us little about his remaining days and death — since we're only halfway through "Living" — and instead lets us piece it together from the chatter of his surviving colleagues and family. Then, the film begins cross-cutting between Mr. Williams' final days on Earth and the days following the funeral as his co-workers reminisce about his sudden dedication to getting a children's playground built. In bits and pieces, we learn that he began personally entreating other departments and superiors in County Hall to get the plan moving and ultimately chose never to tell his son ((the impossibly British-named Barney Fishwick)) about his illness. He died quite suddenly (from everyone but Ms. Harris' perspective) not long after the playground was completed.

Why didn't Mr. Williams tell his son?

Although it's powerfully life-affirming and tear-jerking in its own way, "Living" avoids the kind of sappiness and straightforward emotion that define many movies about the terminally ill. If it were, say, a Nicholas Sparks adaptation, Mr. Williams' cancer diagnosis would no doubt immediately tear down the walls between Mr. Williams and his son, Michael. Tearfully, they would spend his final months reminiscing about their life together and cherishing their remaining time as a family.

"Living" reminds us that even death can't necessarily overcome a lifetime of repressed emotion or the weight of expectation and propriety. Mr. Williams is not only out of touch with Michael emotionally — he's spent so many years passively suppressing his own humanity that he can't even get through a sentence when practicing breaking the news alone. It's telling that the only times he admits his diagnosis (to a co-worker and a complete stranger), he calls the news "a bit of a bore, really." Michael, for his part, would have only had to ask why his father is ditching work or taking half of his life savings out of the bank. Despite burning with curiosity (and somewhat selfish concerns about his own future inheritance) he can't break the veneer of boring civility that exists between them.

Where did Mr. Williams die?

The exact manner of Mr. Williams' death is a small mystery: Since he had told no one beyond Ms. Harris and the insomniac writer Mr. Sutherland (Tom Burke) about his condition, he apparently simply carried on until he collapsed in the course of his daily life. His son regretfully mourns that if he had known, he wouldn't have let his father "leave us like that, in the cold," implying that Mr. Williams died outside on a cold day (though in Britain, really, that could be any day).

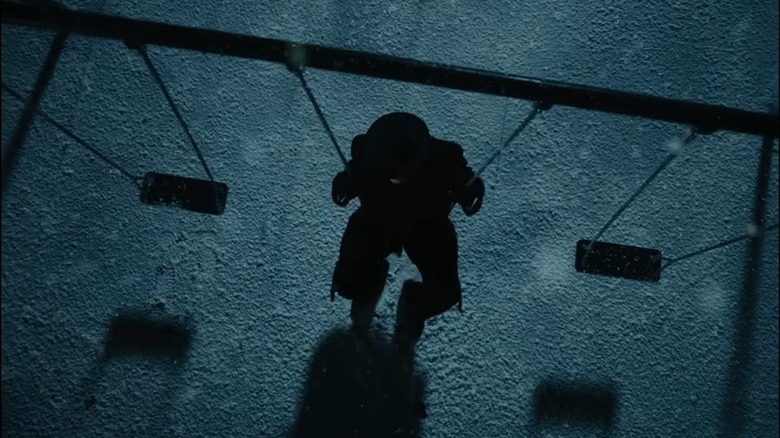

The final scene, when Mr. Wakeling (Alex Sharp) encounters a policeman, offers another clue. The policeman says he saw Mr. Williams singing on the newly built playground in the snow and seems to regret not saying anything or stopping to help the old man get home. Hopefully, Mr. Williams didn't pass away on the playground itself — that would be so coincidentally grim that you'd think it would come up in discussion at his funeral. But it's likely that he died not long after finally finishing "The Rowan Tree" on the swing set in the snow.

It's rather like church

"Living" doesn't have anyone to root against. Except perhaps for cancer itself. But the oppressive forces that plague both Mr. Williams and his younger analogue, Mr. Wakeling, are rather the stifling weight of propriety and the loud silence of individualism. As Mr. Wakeling arrives at the train platform, ready for his first day in the public works department, his jovial and warm attitude is clearly out of place.

His colleagues tell him not to worry — the train platform just isn't the place for joking around and laughing (you know, like a normal person). "It's a bit like church," one of them says without a trace of irony. Later, we learn that this atmosphere of genteel reservation is the very thing that sapped Mr. Williams of decades of his life. He tells Ms. Harris, at his lowest point, that his greatest aspiration in life was to be a "gentleman" like he would see going to work in the morning. But although he's realized this in the utmost — his colleagues respect and fear him to the degree that they don't even walk too close to him on the way to County Hall — it's also crept up on him slowly and robbed him of vitality and empathy. In "Living," life is what passes you by when you're trying to fit in.

Mr. Zombie

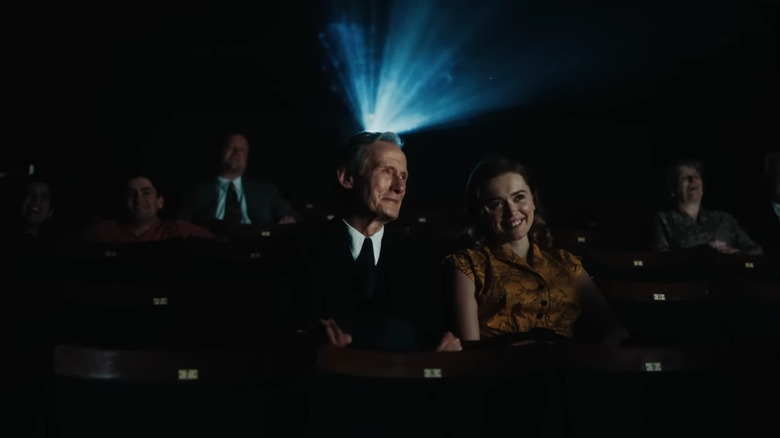

One of the subtlest twists of the knife in "Living" is Ms. Harris' nickname for Mr. Williams at the office. She already feels visibly guilty when she has to explain to her former boss exactly what "Mr. Zombie" is referring to, and it's downright heartbreaking when Mr. Williams asks her to remind him of it just after revealing his cancer diagnosis. From a modern perspective, the use of "zombie" seems to be a bit of an anachronism for 1953: George Romero's "The Night of the Living Dead," which set the model for zombie movies as we know them, didn't come out until 1968.

Ms. Harris does mention seeing a movie that made her think of the idea, but it's possible that this was 1943's "I Walked With A Zombie," or even 1932's "White Zombie" with Bela Lugosi. Those movies, as with all pre-Romero depictions of zombies in cinema, relied more on the Haitian voodoo origins of zombie mythology, in which people are hypnotized or entranced supernaturally. In those days, "zombie" referred to an undead Haitian resurrected through voodoo magic for slavery — which loads Ms. Harris' nickname with some macabre insinuations.

Hedonism isn't the answer

The meaning of life, and the best way to live it, are questions that obviously defy any kind of easy, tidy answers. The early sequence in "Living" where Mr. Williams visits the seaside resort town makes it clear the movie will be offering no such simple resolutions for its main character, either. In a quietly heartbreaking admission, he offers the writer Mr. Sutherland all of the sleeping pills he had meant to kill himself with, after overhearing him complain of insomnia. The libertine Mr. Sutherland points out that "several months" is still time to get some living in, and he takes Mr. Williams out on the town.

While it's affecting to see Mr. Williams connect with a stranger and no longer be alone with his devastating news, "Living" doesn't let us fully enjoy the nightlife. Mr. Williams is quickly more or less in a drunken stupor, resting his head on strangers' shoulders and arousing the concern of a kind bartender. He can't quite finish singing "The Rowan Tree" to a stunned bar, and he later shares an ominous, sad look with Mr. Sutherland outside a burlesque show tent. There is a life outside of work, and outside of Mr. Williams' heretofore-stagnant existence, but hedonism and debauchery ain't it for him. Someone else's version of living needn't necessarily look like your own.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The Rowan Tree

The song that Mr. Williams sings in the bar, and again on the swing set in the last moments of his life, is a traditional Scottish song called "The Rowan Tree." Trees are an eternally useful symbol for the cycle of life and death, as in Terrence Malick's "The Tree of Life" for an obvious example, and the lyrics of "The Rowan Tree" are all centered around this theme. The singer of the song exalts the titular rowan tree, a tree noted for its pleasant yearly gestation of flowers and berries, as being "entwin'd" with "mony ties/ O'hame and infancy" — or rather, many ties of home and infancy.

The rowan tree of the song has the names of lovers carved into its "fair stem" that have now faded, but they live on in the singer's memory; Mr. Williams mentions a partiality to the song, as his late wife was Scottish in descent. Near the end, the singer also has a vision of their mother, who "smiled our sports to see," a nearly perfect description of the mothers calling their children in from the playground that Mr. Williams relates to death later in the film. What "Living" lacks in subtlety it makes up for in a density of meaning, and Bill Nighy's performance of the relevant "The Rowan Tree" accounts for two of the film's most moving moments.

The swiftly forgotten pledge

Perhaps the most quietly depressing moment in "Living" is when ultimately, bureaucracy wins out once more. After Mr. Williams' funeral, his co-workers made a pledge to never turn away from their responsibilities to the public, inspired by his radical transformation in his final months. But within a few scant weeks of his death, new department head, Mr. Middleton (Adrian Rawlins) has fallen into the exact same routine of bouncing requests from concerned citizens to other departments, or just letting them languish in impossibly high towers of paperwork as a last resort.

Mr. Wakeling, clearly thinking of the pledge, stands up at his desk to object. But words fail him as he stands under the newly zombie-like stare of Mr. Middleton and the inexorable, eternal weight of the bureaucratic system. "Living" provides us the solace of Mr. Wakeling's budding romance with Ms. Harris, as the two liveliest characters in the film find plenty of beauty in the world outside of work. But the routines of public works, day-to-day life, and all of the other mundane demands of existence hold sway over the unique vitality that the dying Mr. Williams briefly tapped into. It's a small defeat, but not a crushing one: "Living" traffics in profound meaning, but its characters feel so grounded in reality that we get a sense that somehow, things will turn out alright for them.

The letter to Mr. Wakeling

Considering they exchange perhaps fewer than a dozen words onscreen, it's a surprise when Mr. Williams leaves a "personal and confidential" letter to Mr. Wakeling among his effects. The letter — at least, what we hear of it — finds Mr. Williams paradoxically summing up the themes of happiness and impermanence that define the movie and his final days. At first, he points out that the playground is ultimately "a small thing, and that it will before long go the way of most small things."

But he also exhorts Mr. Wakeling, when he's feeling lost and the "the sheer grind of it all threatens to reduce you to the kind of state in which I so long existed," to remember the playground and "the modest satisfaction that became our due upon its completion." Though they may not be "lasting monuments," our achievements in life are the meanings that can carry us forward. Given the philosophical import and general perspective of this letter (and even its existence in the first place), it's a bit odd that Mr. Wakeling even stops to consider whether Mr. Williams knew he was dying.

People will talk

The relationship between Mr. Williams and Ms. Harris is arguably the central source of conflict in "Living." Mr. Williams, suddenly confronted with mortality after decades of a "zombie" like existence, approaches Ms. Harris twice to spend time together. This is despite centuries of British repression and the societal expectations of when and where old men should spend time with young women. A busybody neighbor sees them having an expensive lunch at Fortnam's and tells Mr. Williams' daughter-in-law, Fiona (Patsy Ferran), who explodes in an oblique rant at dinner that Mr. Williams is too clueless even to understand.

From a modern perspective, and in light of his terminal illness, all the worry about scandal and rumors seems terribly silly. But in the end, Ms. Harris herself tenderly calls Mr. Williams out on his unusual insistence to keep her company late into the evening. And it's this discussion of what's usual and what's not that leads Mr. Williams to finally admit his diagnosis to her and to finally come to terms with it himself. After cathartically admitting that he was drawn to her vitality, even more so than her youth, he realizes that he can apply what he has left of his own to his work instead of scandalizing the "half the street" that works in London.

Slight differences from Ikiru

"Ikiru" is essential viewing for any cinephile, let alone Akira Kurosawa fans. "Living" manages to be a remarkably faithful adaptation of the revered classic while doing just enough to stand apart as its own work. "Living" removes the main character's voiceover, relying a bit more on Bill Nighy's performance to give us a sense of the character's interiority. A scene in which "Ikiru" protagonist Kanji Watanabe (Takashi Shimura) faces down some local gangsters with a newfound recklessness also doesn't appear, perhaps slightly too lurid for the new British setting.

The other small difference is that Ms. Harris gets a new job in a restaurant instead of making toys. In "Ikiru," the toys seem to inspire the construction of the playground in a more direct, parable-like way that ties into the film's themes of rebirth and death. In "Living," the playground isn't robbed of its thematic meaning, but it seems more that Mr. Williams just sets about completing the most recent petition he could get his hands on the day that he walks back into the office with a renewed sense of purpose.

Being called in from the swing set

In the bar with Ms. Harris, Mr. Williams hits on a metaphor for death that tidily sums up the import of "Living," one which indelibly relates to the motif of the playground. Some children, Mr. Williams notes, throw tantrums and whine when their mothers call them in at night. But it's better to be them than the children who sit quietly and wait for playtime to be over. Our final image of Mr. Williams, singing on the swing set that he championed into existence, determined to live despite the cold and impending grip of death, confirms that he avoided the quiet, resigned fate he feared.

Perhaps we've all imagined at one time or another how we'd react to a terminal diagnosis or what we'd do if the world was ending in a cataclysmic disaster. "Living," like many of the other great works from Kurosawa and Ishiguro, points out that we've already received a terminal diagnosis by being born. The battle of how to spend each day is no less dear to Mr. Wakeling for being young. And the creep of expectation and money and routine besets all of us at all times. But it's a matter each moment of deciding whether we're playing our hearts out or just waiting for our mothers to call us to oblivion.