Dog Day Afternoon: 15 Facts About Al Pacino's 1975 Movie Hit That Won't Go Awry

The Oscar-winning "Dog Day Afternoon" lands at the top of the pile in many categories. It is one of the greatest heist films ever made, features some of the best performances ever captured on camera, and was one of the most socially progressive films of the '70s, showcasing LGBT+ characters and their struggles in an era where that hardly ever happened.

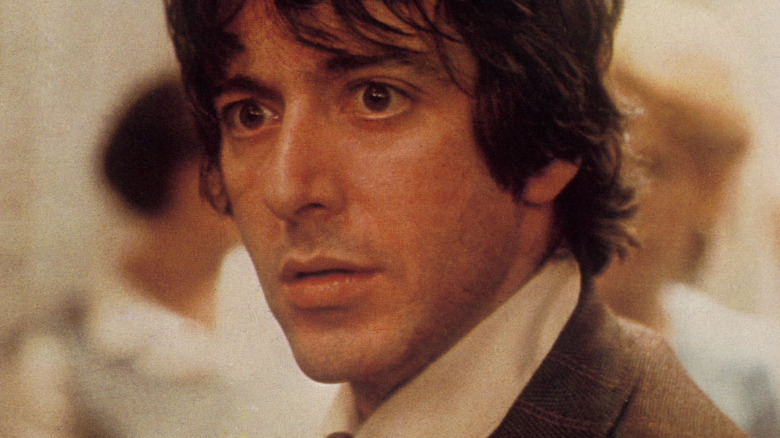

Al Pacino stars in one of his best films while delivering one of the finest performances of his career as Sonny Wortzik, a man driven to rob a bank to pay for his partner's gender-affirming surgery. Things go sideways for Sonny and his accomplice Sal (John Cazale) almost immediately when their third accomplice bails and they learn that the majority of the bank's money was already trucked away earlier. Director Sidney Lumet had collaborated with Pacino two years prior on the classic undercover-cop film "Serpico." Pacino was nominated for the best leading man Oscar for both roles.

This 1975 film was based on a real crime that took place in 1972, though it doesn't follow the true events exactly. Some details were changed for the screen — such as the real bank robber John Wojtowicz having his name changed to Sonny Wortzik — while other elements were translated to screen verbatim, such as his accomplice being named Sal Naturile in both the film and real life. As the 50th anniversary of the film approaches, let's look at some of the most fascinating details of this immaculate crime film.

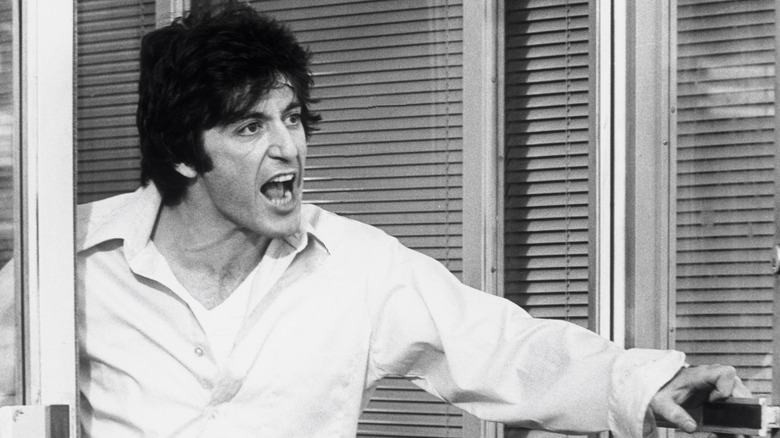

Dustin Hoffman almost starred in Pacino's role

Looking at the film as it exists today, it is nearly impossible to imagine anyone other than Al Pacino in the lead role. Nevertheless, there was a period of time when Dustin Hoffman was poised to take over. Pacino had just starred in director Sidney Lumet's "Serpico" two years earlier, was still buzzing off of the success of "The Godfather" films, and was the obvious pick for the role of Sonny Wortzik. Upon first being approached for the part, Pacino accepted, but he later had a change of heart.

During an interview on "Larry King Live," Pacino opened up about his struggles with alcoholism. "It was during one of those episodes of drinking, in London, that I turned down 'Dog Day'... after I had said yes." The production begrudgingly accepted his resignation and began considering other actors. As was revealed in the biography "Al Pacino: A Life on the Wire," the top replacement candidate was Dustin Hoffman, who had just received his third Oscar nomination for "Lenny."

However, the potential replacement never came to be. One of the producers of "Dog Day Afternoon," Martin Bregman, managed to get through to Pacino. He convinced him to "Stop drinking for a while and read the script," as Pacino explained to Larry King. When the actor followed that advice, everything came back into focus and he said to himself, "Why am I not doing this? I should be doing this."

Pacino re-shot a full day's work after having a boozy epiphany

Though he had started pulling back on his consumption before finally agreeing to take on the role, Pacino was still drinking heavily during the production. As detailed by Andrew Yule in his biography of Pacino and by The Independent in a retrospective on Pacino's relationship with alcohol, in one particular instance, his drinking may have actually fueled a key creative choice that ended up affecting the overall film for the better. After the first day of shooting, Pacino reviewed the footage and was left thoroughly unsatisfied with his performance. "I don't have the guy," Pacino declared, adding that what he saw in himself in the footage was "Someone searching for a character, but there wasn't a person up there on screen."

To address this crisis, Pacino stayed up all night pouring through the script and drinking a half-gallon of wine. He eventually arrived at an epiphany. He had shot the first day's material while wearing glasses, as the script indicated. Pacino's revelation was that Sonny would have forgotten his glasses at home on the day of the robbery because, on some subconscious level, he secretly wanted to get caught. After some convincing, Sidney Lumet agreed to incorporate the idea, which meant re-shooting all of the material they had captured on the first day. The detail may seem insignificant, but it informed Pacino's performance in nuanced ways and enabled him to finally get the character in full.

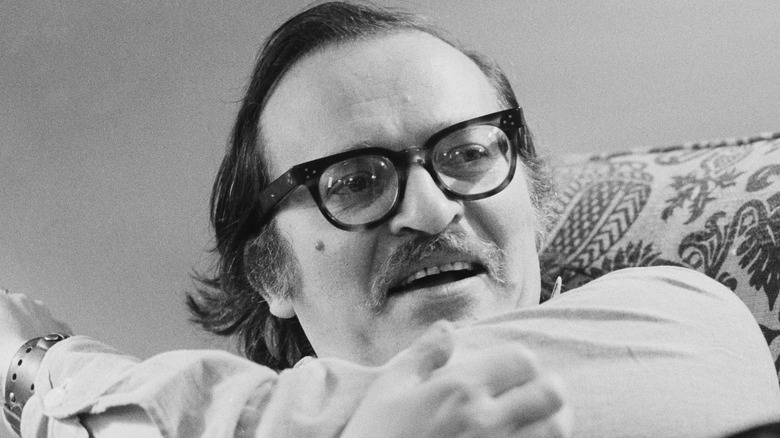

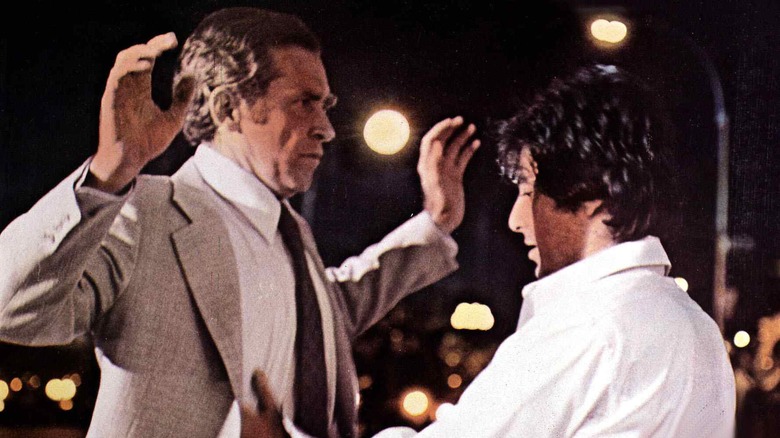

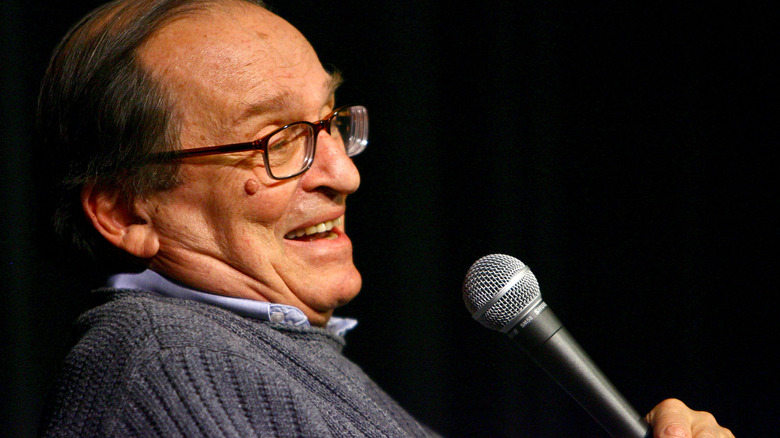

The film made Sidney Lumet change his policy on improvising

After a career that began back in the 1950s, the mid-'70s production of "Dog Day Afternoon" completely changed a key aspect of Sidney Lumet's directorial ethos. Lumet didn't write his first screenplay until 1981 with "Prince of the City." Until then, he was always directing material written by others. As explained in his book "Making Movies," for years, part of Lumet's philosophy as a director was to stick to the text as closely as possible. That changed drastically with "Dog Day Afternoon." Lumet said that the film ultimately stuck to the structure of Frank Pierson's script on a one-to-one basis but, "I'd estimate that 60% of the screenplay was improvised."

As Al Pacino explained to Larry King on CNN, even the iconic "Attica! Attica!" scene was an improvisation thought up on set. The idea came from Lumet's assistant director Burtt Harris, who recognized a potential parallel between what was happening in the scene and the real-life Attica prison uprising that had recently dominated the news cycle.

Given how much of the film was improvised, it is a bit ironic that the film wound up winning the Oscar for best original screenplay — nevermind the fact that the script should have been in the adapted screenplay category anyway since it was adapted from a Life Magazine article written by P.F. Kluge and Thomas Moore titled "The Boys in the Bank."

Lumet made the whole film without artificial lighting

As he explained in his autobiography "Making Movies," Sidney Lumet went into the film believing, "The first obligation was to let the audience know that this had really happened." This sentiment was the guiding principle behind many of Lumet's decisions on "Dog Day Afternoon" and meant placing all focus on naturalism. This didn't just apply to the dialogue and performances but also to the look of the film. After bringing cinematographer Victor Kemper aboard the project, Lumet's very first decision regarding the visual presentation was to avoid using artificial light.

The real bank was lit with fluorescent lights in the ceiling, so Lumet made do with those. When Kemper needed more light for proper camera calibration, Lumet insisted on only supplementing the building's standard lighting with additional fluorescent lights of the same type. This strict approach to diegetic lighting carried over to the exterior scenes as well, and sunlight alone was used for the daytime exteriors.

Still, the nighttime exteriors required a little more creativity. The solution was to rely on the large spotlights mounted on the police van, which were powerful enough to bounce off of the building front to cast light in multiple directions. When supplemental lighting was needed for the crowd shots, Kemper mounted the additional light directly above a real streetlight to keep the effect authentic. When the lights were shut off inside the bank, the interior scenes were lit using the emergency lights that switched on automatically.

Lumet wanted the film to feel accidental

In many films, art direction and production design elements are meticulously designed and chosen to create a precise look in the environments on screen. This might result in unified, aesthetically pleasing, or complimentary color schemes and set dressing. This approach is one that Sidney Lumet employed in many of his films but not on "Dog Day Afternoon." In keeping with the guiding principle that naturalism was of utmost importance in this picture, that had to hold true in the art direction and production design.

Lumet ensured that his art director, Douglas Higgins, and his customer, Anna Hill Johnstone, never spoke to each other. "Whatever happened happened," he told them, "no planning, no color control... I wanted no relationship between the sets and the costumes." This separation made for a more natural look for the film. Lumet, "Wanted a hodgepodge... everything had to feel accidental."

The results speak for themselves on screen as the bank and the people in it feel decidedly un-orchestrated and instead feel true to life. Beyond subtly impacting the viewer, this decision also had an effect on the cast. Being placed in such an authentic environment made everything feel more real. Al Pacino called Lumet one of the true genius directors and spoke to how real the set felt by saying, "You're in a bank robbery ... you don't have to act!"

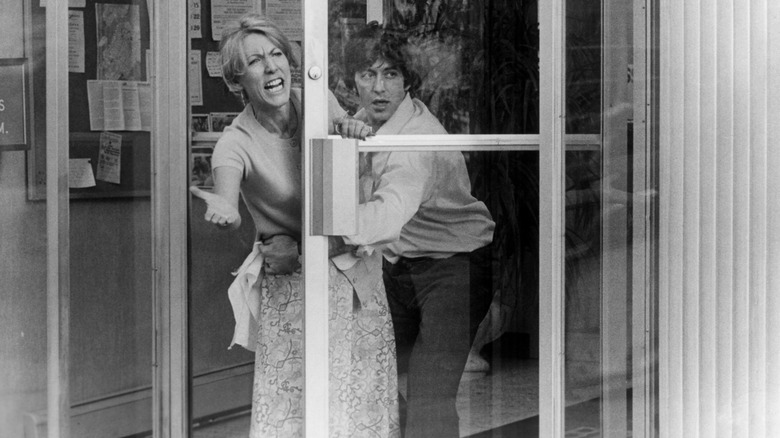

The bank was a real location, except not really

The main benefit of shooting a film on a soundstage is that the environment is totally under the production's control. Sets can be permanently altered, walls can be removed, and lights and cameras can be mounted in ways that would be impossible to achieve on a real location. Given that "Dog Day Afternoon" takes place almost entirely at a single location, it made perfect sense to shoot the movie on a set, except the nature of the plot contained a unique quandary. The action of the film is divided between the interior of the bank and the street just outside of it with characters frequently having conversations and moving back and forth between the two.

To keep the desired naturalistic feel and to avoid interrupting the flow of scenes, Lumet needed the bank and the street to be connected for real. However, he still needed to be able to have complete freedom with the bank and the ability to fly walls in and out at his will. The solution was to find a street that fit the look he was after that also had a large, empty warehouse positioned on it. A bank set was then constructed inside the warehouse to create a hybrid studio/location that opened up to the real street, giving Lumet the best of both worlds.

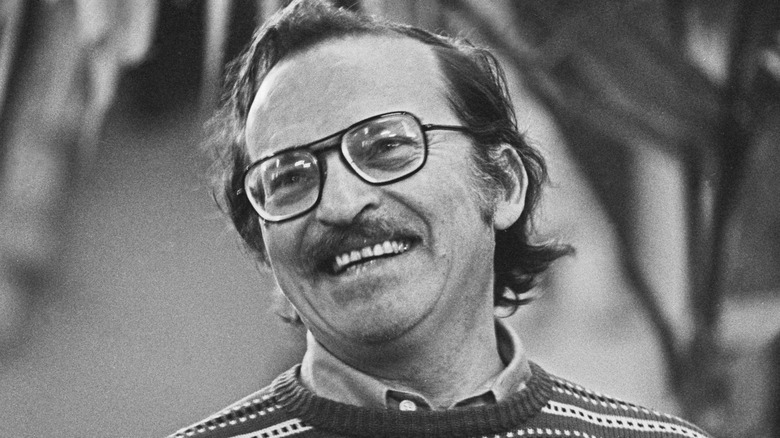

The real Sonny wrote an op-ed to defend his first wife's honor

The bank robber that the Sonny Wortzik character was based on was named John Wojtowicz in real life. After the release of "Dog Day Afternoon," and while Wojtowicz was still in prison, he decided to express his feelings toward the film in an op-ed, which he submitted to The New York Times. The publication rejected his piece but it was later published in Variety in April of 1976, just a month after the film became an Oscar winner (via AFI).

Wojtowicz had mixed feelings about the film. He praised Sidney Lumet's direction and said that Al Pacino and Chris Sarandon (who plays Sonny's surgery-seeking partner) deserved Oscars for their performances. At the same time, Wojtowicz objected to the depiction of his wife Carmen Bifulco (who was renamed Angie in the film).

Wojtowicz was separated from Bifulco and refused to speak to her on the phone during the robbery (unlike what happens in the film). However, he still felt the need to defend her honor in print regardless based on the overtly negative light he felt the film depicted her in. Wojtowicz also accused Warner Brothers of violating their financial agreement with him and objected to the claims that the film was totally authentic, suggesting instead that "I estimate the movie to be only 30% true."

Sidney Lumet got creative to get around technical limitations

"Dog Day Afternoon" was shot on 35mm film back in the days when cameras had many limitations. At that time, the camera could only hold 1,000 feet of celluloid, which meant shots could really only roll for about 11 minutes at a time before the film magazine would need to be swapped for a fresh one. For most productions, 10 minutes would be plenty of time to record any individual shot, but not "Dog Day Afternoon."

The heaviest dramatic scene in the film arrives when Sonny makes two phone calls in a row, one to each of his wives. As explained in his book "Making Movies," Lumet knew it was vital to shoot both phone calls in a single take to allow Pacino to "build up the fullest head of steam." The problem? This full sequence would undoubtedly take longer than the 11 minutes the camera was capable of.

The solution was to ready a second camera positioned as closely to the first as possible and begin rolling on camera two as camera one neared the end of its 1,000 feet of film. This only worked because Lumet knew he could mask the jump by cutting away to the other end of the phone call. For Lumet, recording it in one go wasn't about presenting some impressive long take to the audience, it was about creating the right environment for Pacino to deliver the perfect performance.

The movie helped finally fund the gender affirmation surgery

John Wojtowicz (the real Sonny) decided to rob the bank with the express intent of getting the money needed to pay for his partner's gender affirmation surgery. The bank robbery, of course, ended in disaster, and Wojtowicz ended up receiving a 20-year prison sentence instead of receiving any money.

Though the initial plan resulted in failure, there was a silver lining to be found. He might not have gotten any money from the robbery itself, but the Kingsport Times reported that Wojtowicz was paid $7,500 by Warner Brothers for the rights to his story. Wojtowicz split the money with his partner, and Elizabeth Eden was finally able to get her gender-affirming surgery. Eden and Wojtowicz did not remain romantically involved, with Eden marrying and later divorcing someone else while Wojtowicz married a fellow inmate during his prison sentence.

Though their romance was set aside, the two did remain friends. The Los Angeles Times reported that the two visited each other about once a month until Eden's untimely death at the age of 41 as a result of AIDS.

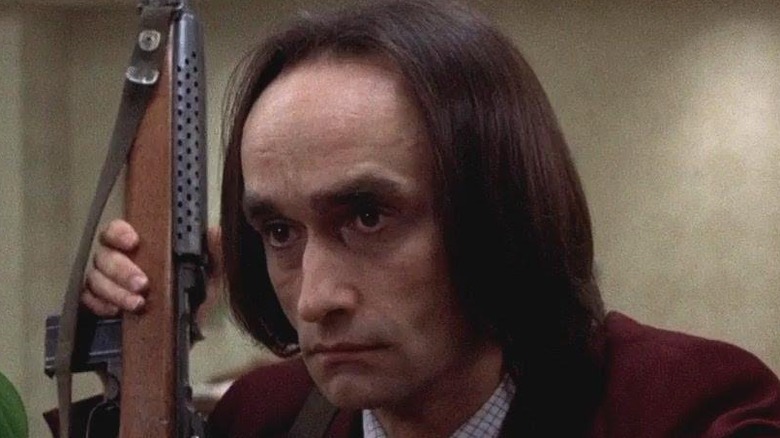

The real Sal wasn't even half the age he is in the movie

In both reality and in the film, Sonny's/John's partner in crime was Sal Naturile. Beyond the name and his function in the crime, the movie Sal and the real-life Sal diverge quite strongly. The biggest departure between reality and fiction was the age. The real Naturile was just 18 years old at the time of the robbery, while the actor who played him on screen, the great John Cazale, was 39 years old — more than double his age. Since he was killed in the attempted getaway following the robbery, not as much is known about the real Naturile as the others involved in the crime.

In the op-ed that he wrote after being incarcerated, Wojtowicz described the death of Naturile as his biggest regret. He also wanted it to be known that his death was outright murder at the hands of the FBI and wasn't depicted appropriately in the film in his opinion. He wrote that Naturile "was murdered by the FBI. It was not necessary for [them] to murder him, because he had been immobilized and unable to do anything, but yet the FBI murdered him before my eyes. I was also immobilized and unable to do anything. The movie never shows this as it truly happened."

Al Pacino fought to get John Cazale on the cast

The real Sal Naturile was 18 years old at the time of the robbery, and the film initially planned to stay true to the facts on that detail. Obviously, with 39-year-old John Cazale ultimately playing the part to perfection, a different creative route was taken. This major deviation from the truth didn't come from screenwriter Frank Pierson, and it wasn't made at the behest of director Sidney Lumet either. This decision was driven by Al Pacino after his best friend and mentor Charles Laughton (not fellow actor Charles Laughton, but an acting teacher with the same name) planted the idea in his head.

Pacino and Cazale had already worked together on both "Godfather" films and in multiple theater productions. In an extended interview from the documentary "I Knew It Was You," Pacino described Cazale as his acting partner and as a big brother figure to him. He reflected on the "Dog Day Afternoon" casting by saying that Sidney Lumet considered casting a young boy in the role to be extremely important, and Pacino agreed. It was Laughton who first suggested to Pacino, "What about John?"

Pacino was taken with the idea and began fighting for Cazale's involvement in the film. Lumet rejected the notion at first, sticking to his guns on casting a teen. Pacino managed to convince Lumet to simply give Cazale a chance to show what he could do in the role, and Lumet was won over.

The real Sonny put his own version of events on film

Over two decades after the release of "Dog Day Afternoon" in 1975, The real Sonny, John Wojtowicz, shot his own version of the events of the robbery. He had been vocal about how far the film veered from reality in the past, famously calling it only about 30% accurate in his op-ed. French artist Pierre Huyghe got in touch with Wojtowicz and gave him a chance to set the record straight.

Rather than coming out as a true-to-life version of the earlier film, Wojtowicz's presentation instead wound up as an art piece. With Huyghe at the helm, he used Wojtowicz to create a video artwork he called "The Third Memory," which was displayed in the Guggenheim Museum. The medium was a two-channel video projection, which basically took the form of a split-screen video in which footage from "Dog Day Afternoon" and new material with Wojtowicz in a recreation of the bank could be presented side-by-side.

The title of the piece refers to the fact that Wojtowicz's personal recollections of events have skewed over time and seem to be directly influenced by the film — perhaps on a subconscious level. The first memory would be Wojtowicz's first-hand account of what transpired during the robbery, the second memory would be the fictionalized account of "Dog Day Afternoon," and "The Third Memory" is intended to represent the resulting conflux of the two accounts as fiction informs Wojtowicz's subjective memories of the event.

Sidney Lumet wanted the actors to wear their own clothes

Sidney Lumet's goal with "Dog Day Afternoon" was to achieve the utmost naturalism. One might assume that would mean sticking to the facts of the real-life robbery as closely as possible, but that wasn't the case. Lumet was less concerned about presenting an accurate representation of the real crime and more concerned with being a totally authentic portrayal of the drama inherent to the situation. The thoughts, feelings, and emotions had to be real even if the circumstances surrounding them were altered from reality.

One of Lumet's tactics to ensure this level of authenticity was to try to erase as much of the separation between the actors and their characters as possible. As explained in his book "Making Movies," Lumet told the actors to play the drama as close to themselves as possible rather than putting on characters. Instead of seeing the characters on screen, he said, "I want to see Shelly and Carol and Al and John and Chris up there ... you're just temporarily borrowing the names of the people in the script."

Sticking with that line of thinking, Lumet wanted to strip away another layer of artifice, "No costumes. They would wear their own clothes." This protocol wasn't strictly followed as the production still made use of a costumer and the actors still made character choices, but the notion of that level of radical authenticity left an impression on the cast that can be felt in their performances.

The real Sonny's wife sued Warner Brothers

John Wojtowicz's wife (whom he was separated from at the time), Carmen Bifulco, was not happy with "Dog Day Afternoon." Beyond her perceived negative depiction in the film, she objected to the film being made at all. One year after the film was released, Bifulco filed a joint lawsuit against Warner Bros. alongside Dell Publishing and Delacorte Press for the accompanying novelization of the film. The 12 total charges included invasion of privacy, unauthorized use of her and her children's likenesses, and defamation.

Most of the charges were quickly dismissed. The Authors League of America stepped in to help get her other charges dismissed, fearing they could set a worrying precedent for other works based on true stories in the future. Bifulco wasn't alone in suing Warner Brothers in relation to the film. John Wojtowicz also sued the company but for different reasons. His claim was for breach of contract with Warner Bros. for failing to pay him the agreed-upon 1% of profits earned by the film. The lawsuit went back and forth in the courts for four decades and was still in litigation when Wojtowicz passed away in 2006 (via The Hollywood Reporter).

The real Sonny participated in a documentary about himself and the robbery

It turned out that John Wojtowicz enjoyed his time in the limelight and the attention that came with the film and being played by Al Pacino. He went as far as to pose in front of the same bank while wearing a t-shirt that read "I robbed this bank" (via BBC). He was also unsatisfied with the depiction of events in "Dog Day Afternoon." After his first two attempts to set the record straight — with his op-ed and the Guggenheim art exhibit "The Third Memory" – his third and final attempt to tell his side of the story accurately was in documentary format. Wojtowicz participated in "The Dog," a documentary made by Allison Berg and Frank Keraudren.

The documentary covered not just the infamous robbery, as it was also a study of his life as a whole. Wojtowicz was personally involved in the project, but the documentary wasn't released until 2013, several years after his death. Even though he served time in prison and held deep regret over how certain aspects of the crime shook out, such as the death of Naturile, Wojtowicz didn't regret committing the crime in general and had no remorse for his actions. In the documentary, he takes an element of pride in what he did. When asked if he would do it all over again, he enthusiastically proclaimed, "You're d*** right I would still go out and do it."