The Ending Of White Noise Explained

Don DeLillo's 1985 novel "White Noise" is widely considered to be a postmodern masterpiece. But like many other works of literary fiction that break into popular culture, its challenging voice, tone, and structure make it practically unadaptable. That hasn't stopped Hollywood from trying, however. According to Variety, multiple studios, producers, writers, and directors — from HBO to Barry Sonnenfeld to James Brooks — have attempted to get versions of "White Noise" into production. But it was Noah Baumbach and Netflix who finally got the job done. In retrospect, it's probably a happy accident that it took so long to shepherd "White Noise" from the page to the screen. Though the story is largely concerned with the existential crises of the 1980s, its themes are (perhaps unsettlingly) more relevant than ever.

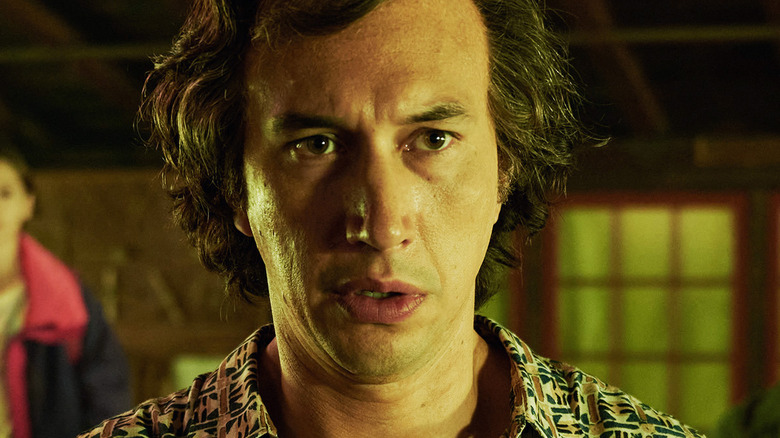

Baumbach's "White Noise" is surprisingly faithful. This is impressive, considering the complexity of the material and Baumbach's inexperience with page-to-screen adaptations. Here, whole sections of the difficult text are lifted word-for-word. Both the book and movie are broken into three sections: Waves and Radiation, The Airborne Toxic Event, and Dylarama. In the first, we meet Jack and Babette Gladney (Adam Driver and Greta Gerwig). In the second, they experience a traumatic event. Finally, in the third, their attempts to resume normalcy escalate into surreal violence. Everything culminates in an unexpected (and awesome) end credits scene. But what does it all mean? DeLillo readers have been poring over that question for decades. The short answer? It's about death. For a more complete explanation of the ending of "White Noise," read on.

How does the title relate to the story?

Consumerism is such a major thread of the "White Noise" story that Don DeLillo actually wanted to call it "Panasonic," but the electronics company's parent corporation, Matsushita, wouldn't give permission. Thankfully, "White Noise" is a more than appropriate title in a variety of ways. The term "white noise" has several meanings. Technically, it refers to a sound containing many frequencies of equal intensity that humans hear as a blunt sort of hissing. It's also used to describe the black and white static (and accompanying noise distortion) of television sets, more commonly observed in the 1980s when flipping between analog channels. Finally, it's an idiom for a huge amount of information that is difficult to mentally filter.

Put simply, white noise is the constant hum of stuff going on in the background. It isn't harmful — some people use white noise machines to fall asleep — but the term itself has a slightly negative connotation in metaphorical use. DeLillo and Baumbach are interested in interrogating the distraction it represents on a deeper level. In "White Noise," characters often listen to the radio and watch TV. Sometimes, actual white noise can be seen and heard, as is the case when Jack visits Mr. Gray's (Lars Eidinger) hotel room. The news is prominent in this film, but it's just one way that the Gladneys are subject to an onslaught of input: They're also exposed to the grocery store, academia, Babette's church fitness class, and her occult books. As Jack and Babette try to ground themselves in their own reality, they're constantly torn between focusing on the big inevitability of life (death) and the other things that make up their existence.

Why do Jack and Babette talk about death so much?

Jack and Babette's marriage locates "White Noise" squarely in the second half of the 20th century. It's the fourth such bond for both of them; their family of six is blended from their previous attempts at domestication. As Denise (Raffey Cassidy) puts it, their decade, the 1980s, is the "we all get to do whatever we want" era. That Jack and Babette remain together when marriage is utterly disposable to them both indicates that they're really in love. But death gets factored into every equation in "White Noise," from choosing which gum to buy to the question of which spouse loves the other more.

Babette introduces this tension. She tells Jack that she loves him so much, she couldn't go on without him, and believes he fears death more than being alone. But this isn't true for Babette in practice. After Jack confronts her about her pills, she describes her anxiety using a series of either-or statements. "Sounds like a boring life," Jack replies. "I hope it lasts forever," she answers woefully. She later admits as much when she comes clean about Dylar and Mr. Gray, telling Jack, "I just fear death more than I love you, and I really, really love you." Ironically, Babette is sacrificing the quality of the life and love she has by cheating on Jack (albeit with a ski mask, so she can disassociate) and compromising her memory, all for the sake of coping with her crippling dread.

Why compare Hitler to Elvis?

Jack's colleague and friend Murray Siskind (Don Cheadle) wants him to attend one of his lectures, in the hopes of giving his reputation some gravitas. Murray is an Elvis Presley scholar who resents another professor's advancement because, in his opinion, that academic only sees Elvis as Elvis. To Murray, Elvis is Hitler. Murray doesn't mean that Elvis is a genocidal despot — he's making an analogy to Jack's work. Jack started the Hitler Studies program not because he's a fan of the dictator, but because he's fascinated by Hitler as an outsized historical figure. Though Hitler and Elvis are both dead, their legacies will live on forever, which is a kind of immortality. For Jack, unpacking this conqueror of death's appeal gives him a much-needed sense of control.

Murray is summarizing Elvis' early life for his class when Jack interrupts. They proceed to give dueling speeches about their chosen subjects. The scene underlines parallels in these figures' relationships with their mothers and their eventual ability to draw and rouse enormous crowds. Both Jack and Murray submit that fear of death, particularly following the deaths of their mothers, caused a shift in worldview for both Hitler and Elvis. In the case of Elvis, the meaninglessness of his mother's demise caused him to self-destruct. But in Hitler's case, the fear of death turned outward and became widespread violence. "White Noise" touches on this idea several times. Murray tells Jack that he can either be a die-r or a killer. Jack tells Murray's students that Hitler was able to win people over because there's safety in the crowd, and comfort in the idea of someone else dying.

Will Jack die from the airborne toxic event?

The middle section of "White Noise" is eerily familiar to everyone who lived through the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. A train collision results in what's first called a feathery plume, then a black billowing cloud, then an airborne toxic event. Exposure to Nyodene D is said to cause sweaty palms, followed by vomiting and shortness of breath, and eventually, death — but this death might come within 15 years. Jack is unknowingly contaminated when he gets out of the family's station wagon to pump gas. He goes back and forth with the simulation evacuation technician (who's using this real emergency as a research modeling opportunity) about whether he might die or definitely will die as a result of this exposure.

The technician basically tells him that, despite the best science, they just can't say. But whether Jack will die of Nyodene D isn't the point, which is why it's left ambiguous. What matters is that Jack has to live on with this ambiguity. Nine days later, the local government gives residents the okay to return home, and everyone resumes their normal lives. Jack is hesitant to see doctors, and tells himself that he's fine, but he can't quite shake the idea that his life might've been dramatically shortened by the airborne toxic event. Eventually, he tells Babette, "I'm tentatively scheduled to die," and tells Murray about his nighttime visions of death. Murray says that most people repress the suffocating knowledge of life's eventual end, but acknowledges that Jack, who's obsessed with death, doesn't know how. Jack laments that he can't quell his tension by analyzing the problem — not just of death, but of living with the inevitability of it.

What does Dylar actually do?

What Dylar is and how Babette gets it are the central mysteries of "White Noise." Denise first sees the drug's name on a pill bottle that Babette tosses into the garbage. Jack manages to get neurochemist Winnie Richards (Jodie Turner-Smith) a pill to analyze; she reports back that it's a psychotropic substance in a polymer slow-release capsule, and that it's not officially on the market. This lines up with Denise's independent research and Jack's call to Babette's doctor, who's never heard of Dylar and doesn't prescribe it. After repeated prodding, Babette tells Jack the whole truth. She signed up for some top-secret clinical trials, and when they were discontinued because of Dylar's potentially dangerous side effects, she began exchanging sex for a supply. We don't know whether or not Dylar cures Babette of her acute fear of death, but it does make her forgetful, and causes her to confuse words with objects.

Jack remembers this when he tracks down Mr. Gray after stumbling upon the newspaper ad. His motel room is littered with pills. He's filthy, unwell, and strung out on his own supply, which he pops like candy. He's also absent-minded (he forgets Babette's name) and confuses words and objects, just like she does. When Jack tries to buy Dylar, Mr. Gray tells him that the drug has proven to be a failure, though the formula could be successfully refined in the future. Ultimately, Dylar is meant to critique modern society's preference for easy solutions. Its failure symbolizes how the finality of life gives it meaning.

Why does Jack shoot Mr. Gray?

When Jack arrives at the Roadway Motel, he has two possible objectives. He's curious about Dylar, as he's struggling to grapple with his potentially imminent death, but he's also entertaining the idea of killing Mr. Gray. He brings his gun with him, and considers his previous conversations with Murray as he drives. Murray's assertion, "Maybe violence is a form of rebirth, and maybe you can kill death," rings loudly in Jack's head. Murray has also suggested that Jack chose to study Hitler because he thinks, in a bizarre way, that the dictator can protect him: Some people are larger than life, but Hitler is larger than death.

When Jack wants to know more about Mr. Gray, Babette refuses to say because of the jealous madness this might drive him to, even though Jack assures her he's not a killer. But in the car, he says to himself, "Steal instead of buy, shoot instead of talk." This strongly implies that murdering Mr. Gray is his primary motivation. He's decided that killing the man who cuckolded him is a better remedy for what's ailing him than Dylar (though he could still steal the Dylar once he's offed his victim). When Jack corners Mr. Gray in the bathroom, he calmly declares, "I'm a former die-r who is now a killer." Then he shoots him in the shoulder. The presence of Hitler, Mr. Gray, and Jack's increased machismo throughout "White Noise" are meant to show how the accumulation of power and the use of violence are misguided attempts to feel invincible in the face of implacable death.

What do the German nuns represent?

Mr. Gray, having only been shot twice, dislodges the third bullet, which grazes Babette in the leg and Jack in the hand. Realizing that violence was pointless, the wounded trio shows up at a hospital run by German nuns. Over Jack and Babette's beds is a small painting of Pope John XXIII and President John F. Kennedy, holding hands in heaven. Babette asks their caretaker what the church currently has to say about heaven. She and Jack are taken aback by the nun's impatient response: She's agnostic and only concerned with tending to the sick and injured. "You don't believe in heaven," Jack asks, exasperated. "If you don't, why should I?" she quips back. "If you did, maybe we would," he fires back. "If I did, you would not have to," she says, winning the argument.

That they're nuns and German is very important. Babette thinks men are killers, but women are more constructive than destructive. Jack is also just learning German, so the fact that these women — who have a kind of wisdom he doesn't possess — speak it shows how he's only beginning to understand true wisdom. There's also a deep irony in the notion that the religious figures who are Jack and Babette's literal saviors are not themselves religious. The Gladneys want the nun to have real faith because there's peace in the idea that they're wrong and the church is right. But "White Noise" turns religion and its rituals into another Dylar: an imperfect placebo for the fear of death.

What's the deal with the supermarket dance number?

After leaving the nuns' hospital, Jack and Babette take their family grocery shopping at the same supermarket they've shopped at throughout the film. The song "New Body Rhumba" by LCD Soundsystem plays over the store's loudspeaker, and all the customers begin to dance as they pick out boxes of cereal and cans of Pringles and add them to their carts. The Gladneys spin each other around and check out as a family. The academics rhythmically parade down the generic aisle. Townspeople lift fruits, vegetables, and prepackaged goods into the air, as if offering up religious praise. In the background, a wall of posters enthusiastically advertises the price of everything. There's both an energetically fun and oddly hypnotic quality to everyone's motion.

Don DeLillo's novel ends in the supermarket as well. But while DeLillo's message is the same as Noah Baumbach's, the vibe is decidedly different. In print, it occurs to Jack that secular modernity is full of its own beliefs and rituals, and shopping for groceries is one of them. When their local store is rearranged one day, the public — especially the elderly — are flung into a panic. Only the generic products remain where they've always been. In both versions, ending with shopping as a trance-like experience highlights the extent to which consumerism has become a religion of its own. It's also noteworthy that in the film, Jack compares the acceptance of death to walking calmly toward sliding doors. This is exactly what he and his family do as "White Noise" comes to a close.

How does it compare to the book?

Noah Baumbach's take on "White Noise" makes a few changes to the source material beyond the interpretive dance at the supermarket, which stands in for Jack's closing thoughts. Some of the characters' backstories have been tweaked, and the narrative has been streamlined. Essentially, the movie is a trimmed-down version of the book, with fewer characters and less dialogue, including inner monologues. Other changes include visual elements, like the dance sequence, that were presumably added to make the plot more active.

In the book, all of Jack and Babette's children, including Wilder (Henry and Dean Moore), are from previous marriages. He's also a more significant character. Heinrich (Sam Nivola), Denise, and Steffie (May Nivola) are a few years younger. Wilder's mom and stepdad worry about his development, and he nearly dies in the last chapter when he rides his tricycle across a busy highway. Beyond the family, Murray Siskind is subject to changes as well: He's Jewish in DeLillo's "White Noise" and Black in Baumbach's film. In the latter version, it's Murray who gives Jack the gun and loans him his car. In the book, Babette's father Vernon (who doesn't appear in the movie) provides him with the pistol, and Jack steals his neighbor's car to go looking for Dylar and revenge. The man we know as Mr. Gray in the movie is named Willie Mink in the novel. DeLillo's Babette doesn't show up at the hotel, and isn't involved with the shooting. Finally, most scenes involving the car are either expanded or original to the movie. They go a long way towards making Baumbach's "White Noise" properly cinematic.