Babylon Review: Sex, Drugs, And Hollywood

- Gorgeously shot and edited

- Intermittent moments of true greatness

- A lot of passion up on that screen

- The LENGTH!

- At times has difficulty balancing its ensemble

Spurred on by the precarious nature the exhibition industry has found itself in post-Covid, filmmakers like Steven Spielberg ("The Fabelmans"), and Sam Mendes ("Empire of Light") penned nostalgic love letters to the cinema that has sustained them throughout their lives. But for his contribution to this recent storytelling trend, director Damien Chazelle has taken a considerably more chaotic approach. His latest "Babylon," is an ambitious, unwieldy and strangely vulgar epic set in the late 1920s as the silent film era gave way to the advent of the talkies. It reads much less like a tear-stained, cursive scrawled love letter to the motion picture business than the fanatical rantings of a man afraid his vocation is about to disappear entirely. There's no candlelight, no quill pen, no inkwell. Only blood, sweat and other bodily fluids messily smeared by hand along the cave walls.

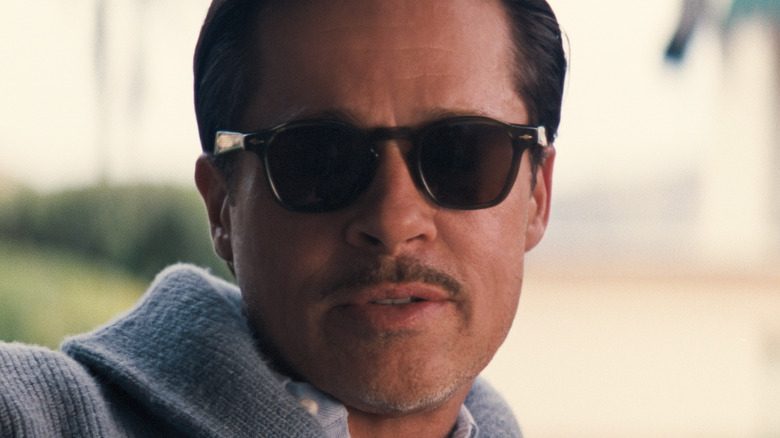

The film follows an ensemble cast featuring Diego Calva, Brad Pitt, and Margot Robbie at the peak of silent cinema, exploring this era of Hollywood with a frenetic, drug-addled pace borrowed from Paul Thomas Anderson's "Boogie Nights" (which borrowed it from Martin Scorsese's "Goodfellas," which came from Francois Truffaut's "Jules & Jim"). Chazelle traces a lineage of maximalism to a past he vividly recreates as more lawless, more incendiary, and more alive than the more conservative world that would usurp it when the moving pictures started making their own sounds. Like some of the other 2022 love letters to cinema, "Babylon" is a film that also flirts with exploring commentary in light of the nation's pandemic-time reckoning with many social justice concerns. Chazelle avoids the mistakes made in "Empire of Light," where Mendes got entirely too much dip on his chip.

But the finished product still proves somewhat unwieldy, given just how much must be juggled and how much of the viewer's time and attention it expects as it does so. It doesn't all quite come together as well as one might hope, but there's too much passion on display to quibble so heavily over its faults.

Dionysus wept

Were the studio's marketing for "Babylon" to be believed, the film was positioned as some kind of nonstop thrill ride of excess, hedonism, and dark humor. But the film's Baz Luhrmann-lite trailer and art all stem from its opening 45 minutes or so, with a bombastic sequence introducing all the main characters at a party thrown by studio exec Don Wallach (Jeff Garlin, looking a little too much like Harvey Weinstein). Wallach throws these legendarily ostentatious parties, and for this one, he's demanded an appearance from an elephant, a task delegated to Manny (Calva), a go-fer Wallach's right hand man Bob Levine (Flea) tasks with all manner of odd and peculiar jobs.

It's at this party that Manny meets Nellie LaRoy (Robbie) a nobody from New Jersey who already believes herself to be a star, and in the believing is able to become one for real. We're also introduced to other semi-protagonists like: Brad Pitt's Jack Conrad, a womanizing movie star who seems to know everyone; Sidney Palmer (Jovan Adepo), a jazz trumpeter; and Lady Fay Zhu (Li Jun Li), an entertainer who moonlights as a scenarist and title writer for the pictures. These and more background characters all have their parts to play across this decade spanning tale, but before we can know more about their hopes and dreams, Chazelle puts significant creative energy into making this absurd party and its Dionysian largesse a worthy spectacle to feast upon.

But the direction he takes is something of a surprise. Rather than recreating the glamour of "La La Land," there's an almost bro-y level of vulgarity on display, with every background sexual gag or moment of regurgitation presented with the adolescent gross-out humor of "The Hangover." It's a curious choice, to turn an era usually treated with pristine reverence like "Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom" as conceived by the cast of "Jackass Forever." At first blush, devoting nearly a third of a three hour movie to a singular party to introduce the principal cast may seem wasteful from a story structure perspective, but it's one that pays off later in the film.

The crackling energy of the party carries over into one of the film's most thrilling set pieces, showing a day in the life of producing silent pictures from multiple perspectives. Standouts include Spike Jonze as a mad German director and Samara Weaving as an actress about to be replaced by Robbie's LaRoy. However, in seeing this process, in seeing how wild and unfettered this world was at the time, it begins to make perfect sense why these artists all tended to end their days surrounded by the cathartic opulence of Wallach's parties. Chazelle is able to halt the kaleidoscopic momentum of these sequences to show the yield from all their madcap shooting, to show a couple of distilled silent cinematic moments that came out of all that tragicomic chaos. In that pause to collect the audience's breath, it all seems worth it.

Too bad it cannot last.

The kid stays in the picture

"Whiplash" was about the cost of perfection and whether or not revelatory artistic expression was worth the abuse and psychological torment that often goes into it. "La La Land" was about the ineffable, fleeting nature of love, exemplifying Michael Mann's often repeated aphorism "time is luck." "Babylon" synthesizes the two, placing the finished product of cinema upon a high pedestal, presenting an unsustainable world that produces it, then pondering whether or not the sacrifices placed into the bubbling cauldron of cinematic alchemy are worth the magic that winds up on the screen. There's a bit of a love story at the center between Manny and LaRoy, but none of the characters are ever given real room to love or hate one another because they each are wrestling with their own demons and aspirations.

Manny goes from being the hired help to a studio executive because of his innate ability for assimilation. Every one of the close contacts he makes in the film's first act in some way or another fails to fit the paradigm for stardom, but it's more that that paradigm is always changing, and the market forces at play that decide whether someone belongs in front of the camera are as cruel and uncaring as the artform itself is loving and empathetic.

Sound changes everything, as we see in the film's funniest sequence showcasing talent getting used to the more controlled and hermetically sealed world of studio production. But the change proves darkly poetic in addition to practical.

The same fire and tenacity LaRoy possesses in spades that makes her such a star becomes a hinderance when audiences balk at the grating quality of her Jersey girl accent. Sidney is able to be the face of jazz films aimed at a burgeoning Black audience in the south, but when the studio lights make his skin look too pale in comparison to his darker skinned co-stars, he must mark his face with burnt cork like a minstrel, or the movie won't sell. Pitt imbues Jack with all his own movie star charm, but for a man who made a career saying so much with his face and his eyes, having to get it across with the spoken word makes him appear foolish and unwatchable.

Manny, who initially allows his pragmatist skills to mute his love for the art of it in his hopes to succeed and fit in, is able to weather the changes better than most, but its his connection to LaRoy and her fall from graces that dooms and damns him.

The shift from silent movies to the talkies could just as easily be any other transformative moment in Hollywood history for Chazelle. At times, it truly feels like he's raging against the current state of the industry and the sense that the magic is either dying out or being supplanted by something more artificial, but by tracing a throughline from studio microphones to, say, CGI or something. He also, perhaps inadvertently, asserts that this sense of dread cinephiles feel, this haunting ache that the castles we've been building in the sand are soon to be washed away by the tide... it's all just part of the cycle.

We all love to say "they don't make 'em like this anymore," but "Babylon" almost seems to say, "maybe they never did." We've just had enough time and distance not to associate our love of the enduring art with the craven ugliness that characterized the making of it. Your mileage will vary as to whether the film's final epilogue is too on the nose or absolutely transcendent, but maybe the litmus test is simpler than that; maybe how you feel about "Babylon" will depend on how steeped in irony your tears are when Nicole Kidman steps into frame under the AMC logo.

"Babylon" debuts in theaters on Friday, December 23.