That's What's Up: Stan Lee's 10 Greatest Comics

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: If I want to experience the best of Stan Lee as a writer, what should I be reading? — via email

For me, Stan's greatest contribution is the role he played off the page, as Marvel's original editor and the person who became the public face of comics. He was the first creator that would speak directly to the fans, putting his own name and those of his collaborators right there on the page and in the letter columns to give people the sense that they could actually interact with the creators behind their favorite stories. It set the tone for how the entire industry would function, and made the jump from fan to creator seem like it was possible for everyone.

If that was all he'd done, he'd still be one of the most important figures in comics history. But while the artists he collaborated with, like Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, often did the bulk of the plotting and brought plenty of great ideas to the table, Stan was the one putting the dialogue on the page, and the fact that he did that for some of the greatest comic book stories of all time is a staggering achievement all on its own. If you really want to see it in action, here's ten that you need to check out immediately, if not sooner.

Identity Crisis (Amazing Spider-Man #600, 2009)

In recent years, Lee has mostly stepped away from any regular comics work, instead just showing up for special occasions every now and then — although he is still the credited writer of the Amazing Spider-Man newspaper strip. Still, the best thing he wrote in the entirety of the 21st century is a charmingly goofy little backup alongside artist Marcos Martin that ran in Amazing Spider-Man #600.

Not to be confused with the truly awful DC event of the same name (or the less awful but somewhat mystifying Spider-Man story from 1998), "Identity Crisis" is about Spider-Man explaining all of his troubles to a psychiatrist. Not the usual troubles like supervillains, you understand — the troubles of being a fictional character whose personal continuity is subject to being tweaked and retconned by his creators.

The twist? The psychiatrist, who has the groanworthy name of "Gray Madder," is drawn by Martin to look just like Stan Lee. Actually, that's not true — the actual twist is who Madder goes to when Spider-Man's questions drive him to seek therapy. It's a bit of a deep cut, but it's the best punchline Lee's been a part of for years.

Bedlam at the Baxter Building (Fantastic Four Annual #3, 1965)

While Stan Lee had a hand in creating virtually every character that was featured at the dawn of the Marvel Age of Comics — with the notable exception of Captain America, who was punching out Hitler in 1940 courtesy of creators Jack Kirby and Joe Simon — there are a handful that he clearly cared about more than others. His involvement with Avengers and X-Men, for instance, was relatively short-lived before he handed them off to other creators. With Fantastic Four, however, he and Kirby collaborated for 102 issues straight, plus six more annuals, and it's there that they did some of their greatest work.

But while "Bedlam at the Baxter Building" might not quite hit the operatic highs of Galactus descending from space to eat the Earth or Dr. Doom blasting the FF's skyscraper into space, it's still a must-read book for me. This is, after all, the one where Reed Richards and Sue Storm finally get married, and winds up involving pretty much every other character in the Marvel Universe at that point, all attending one of their world's most important events. It's a showcase of just how cohesive that universe was, and with Dr. Doom hypnotizing every supervillain in New York to attack the blessed event, it's just plain fun to read.

The best bit, though, is the end, when two familiar figures, Stan and Jack themselves, are refused entry into the wedding and sullenly head back to the office to make the next issue. That's what was so great about Stan's contribution to the early days of Marvel — with gags like this, he and Kirby embodied that bridge between our world and the one they were creating on the page.

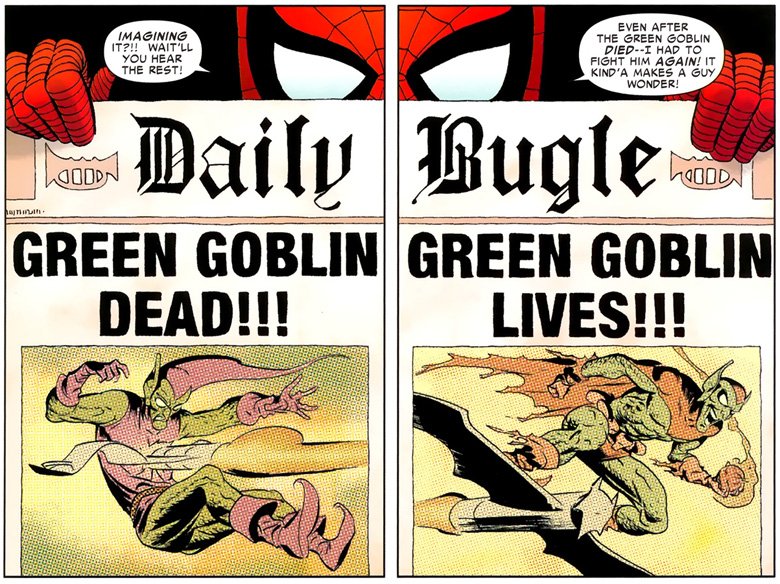

The Sinister Six (Amazing Spider-Man Annual #1, 1964)

Spider-Man was another one of those characters that Stan was writing for the long haul — a full hundred issues in a row, and then off and on for the next few years until Gerry Conway got the job of killing off Gwen Stacy and potentially becoming the most hated man in comics circa 1973. In a lot of ways, that's the book that defined his first decade at Marvel, and it's easy to see why. The FF might've been Marvel's first family, but Spider-Man was the character so popular that they put him on the paychecks.

Stories like this one are why. If "Bedlam at the Baxter Building" was a lighthearted romp with romance and slapstick superheroism, "The Sinister Six" is an all-out action-packed thrill ride that hits the ground running and doesn't slow down for a full 41 pages. As the title implies, it's Spider-Man taking on every single one of his major villains, one right after the other, and while it feels a little old-fashioned when you look at it 50 years later, it still holds up as one of the greatest fight comics of all time.

To be honest, the star here is Steve Ditko. His awkward, spindly figures — perfect for Spider-Man's earliest adventures and Dr. Strange's weird sorcery — always made him the weirdo of the original Marvel roster, but the splash pages of Spidey duking it out with each of the villains are among his best work ever. That said, Stan's dialogue features Peter Parker getting madder and madder at these villains, winding up with some real gems like calling Electro a "high-voltage heel."

The Peril and the Power (Fantastic Four #57 - 60, 1966)

In Fantastic Four #50, Lee and Kirby had basically told the biggest possible story the superhero genre had ever seen up to that point, a three-part saga that defined "event" comics by basically having God show up in a purple hat and threaten to eat the planet. It's great, but it does raise a pretty staggering question: where the heck do you go after that?

If you're Lee and Kirby, you just start reminding everyone that you also created Dr. Doom, and that he's the greatest supervillain of all time. Thus: "The Peril and the Power," the amazing story where Doom fools the Silver Surfer into thinking that he's a nice guy and then immediately hits him with a science-taser, steals the Power Cosmic, and then proceeds to beat the ever-lovin' blue-eyed mess out of the FF for the next four issues.

In addition to boasting one of the all-time great Ben Grimm fights and a climax where Reed manages to outthink Doom despite being woefully outmatched, this story has Lee's operatic superhero writing at its best. He's always great at lending Doom his bravado and self-serving grandeur, and the scene where Doom is running a con on the Surfer — basically just standing there pretending to like puppies until the Surfer turns around for half a second — is genuinely great.

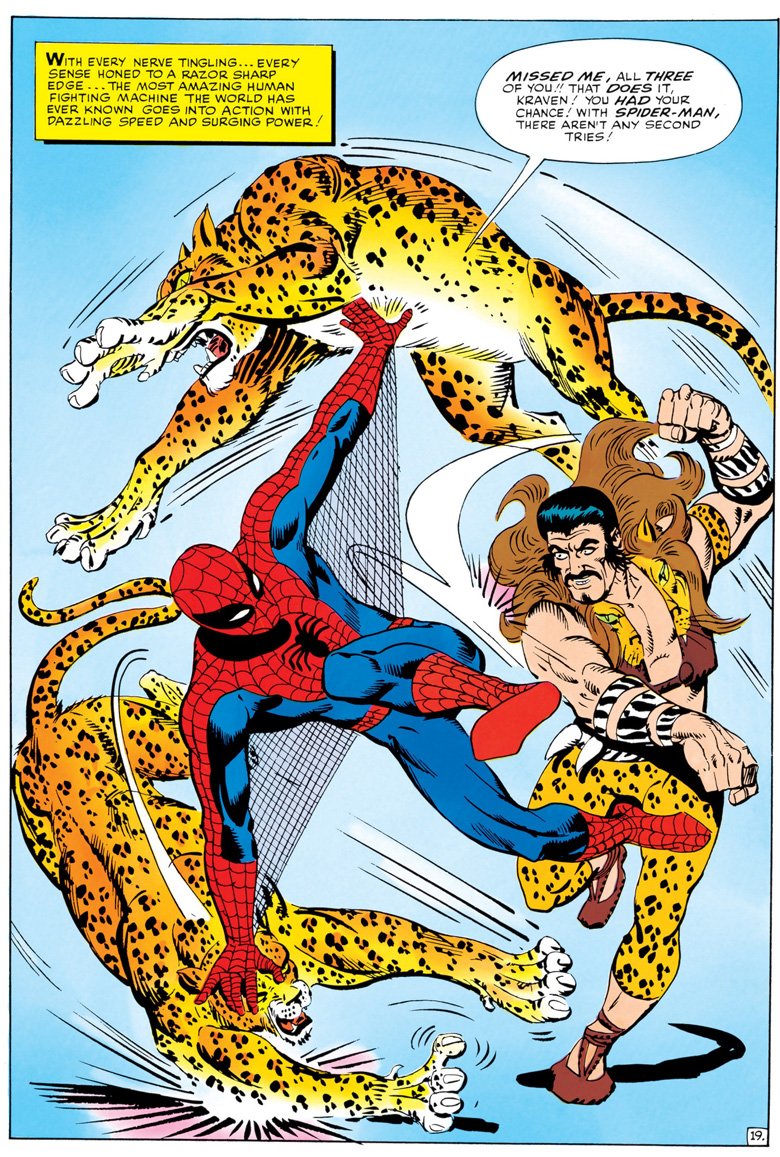

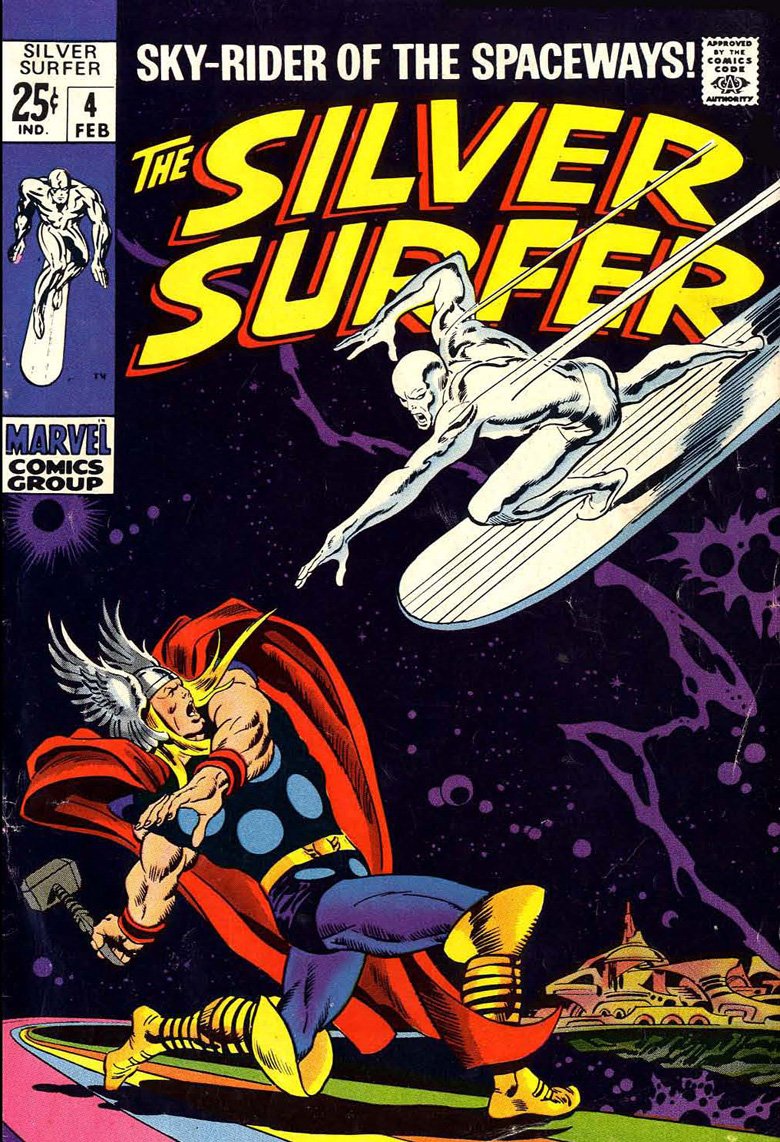

The Good, the Bad, and the Uncanny (Silver Surfer #4, 1968)

Whenever I've seen interviews or meet-and-greets with fans where someone has asked Stan Lee who his favorite character is out of all the heroes and villains that he's created, he always has the same answer: the Silver Surfer.

That might be surprising, but it's also easy to see when you read his Surfer work. There's a rare thoughtfulness to it, and it's in these stories that Stan really gets into cosmic morality and parables, dealing with the challenge of writing a superhero who's essentially a pacifist. Although to be honest, very little of that is on display here. In its absence, we just have another beautifully done fight comic from Lee and John Buscema.

There's a little bit of it, of course — Surfer starts out the story hanging out with some lions and hippos because, despite being considered savage, they lack the cruelty that's so common in human beings. Mostly, though, it's about Loki being Loki and deciding that the best way to ruin Thor's day is to convince the Silver Surfer that he should crash a party in Asgard and get into a fistfight with everyone there. It's a perfect clash of weird sci-fi and superhero fantasy, and Buscema draws the sneeringest Loki that you're likely to see anywhere.

The Coming of Galactus (Fantastic Four #48 - 50, 1966)

For any other pair of creators, a story like "The Coming of Galactus" would unquestionably be the single best thing they'd ever done. The fact that it only rounds out Lee's top five — and might not even rank that high on a list of Kirby's greatest hits — says a lot about how many truly great stories he's been a part of.

To say that this story is a game-changer is underselling things quite a bit. I've already talked about how it was the biggest story that superhero comics had ever seen, but the impact that it had on comics can't be measured. It's the blueprint for the big event, the foundation on which everything from Crisis on Infinite Earths to Infinity Gauntlet is built on. It's a story where every single thing that readers had seen in these comics is in danger, and where, at the end of the day, the main characters have to confront the fact that there are cosmic forces that are literally beyond their ability to deal with on their own.

And the wildest thing? It actually ends halfway through #50, so that we can move on to Johnny Storm's first day at college. The civilian soap opera and the cosmic heroics, and the way they blend together, is exactly how Lee and Kirby revolutionized comics.

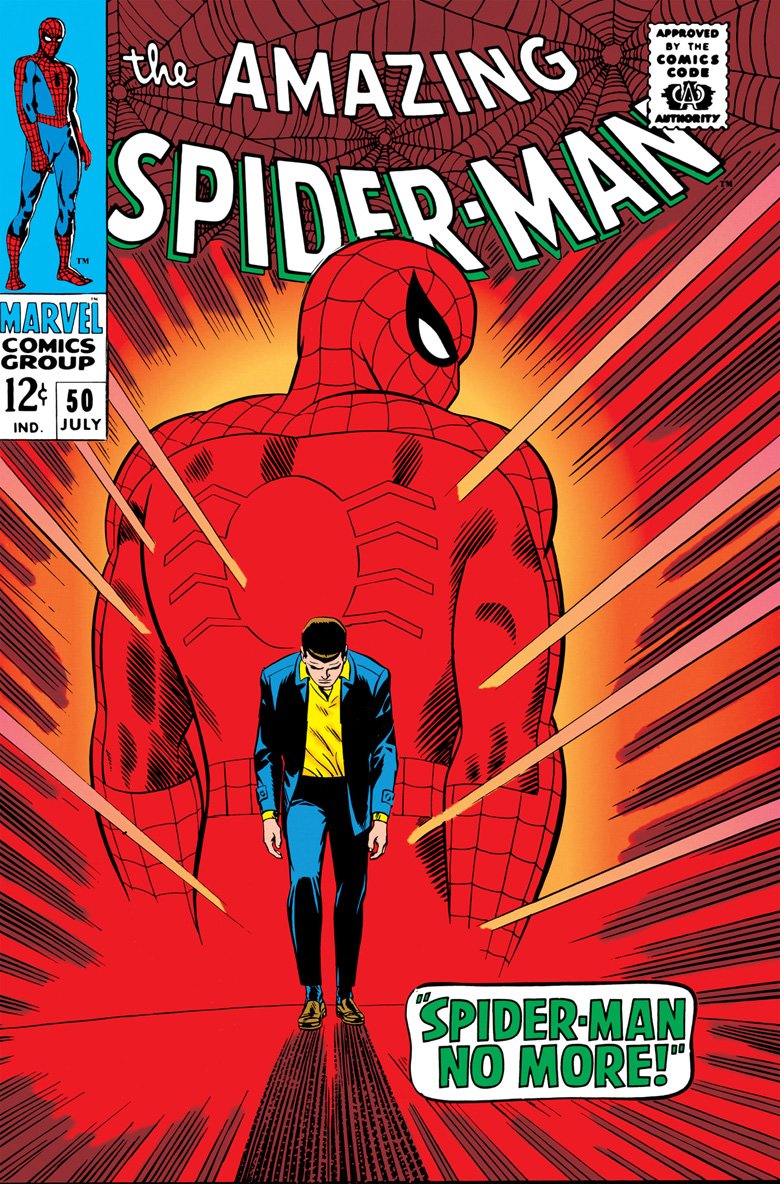

Spider-Man No More! (Amazing Spider-Man #50, 1967)

In Amazing Fantasy #15, Stan Lee and Steve Ditko established that Spider-Man's fatal flaw will always be his very relatable desire to just stand by and let things happen as they may without his intervention. It's the reason that the line about power and responsibility is repeated so often in those stories, because it has to be a constant reminder.

In Amazing Spider-Man #50, Lee and John Romita Sr. put a new spin on that same idea, one that actually improved it. After years of adventures, they told a story in which Peter Parker finally got tired of having all of his heroic efforts rewarded with endless problems, and gave it up. There was even a justification: hadn't he done enough? Hadn't he made up for his one mistake with 50 issues of fighting against evil?

The answer, of course, was no, and it marked a massive change for Peter Parker as a character, one of the moments that makes him truly great. Even though he tried to give it up, he couldn't — his nature had changed from the person who wants to stand by to the person who can't, and replaced that fatal flaw with a new one in the process. That was the evolution of what Lee, Ditko, and Romita had done with Spider-Man over the course of four years, and it made for a great story.

This Man, This Monster (Fantastic Four #51, 1966)

Remember that thing I said a minute ago about how Lee and Kirby were left with the problem of how to top the Galactus story, and managed to do it within a year? That's actually not true. It's arguable that they did it the next month.

Ever since he made his first appearance, Ben Grimm — the ever-lovin' blue-eyed Thing — had been the prototype for the Marvel superhero. He was powerful, but that power came with a price, and he spent as much of his time being tortured about his misshapen rock monster body as he did using it to clobber the FF's enemies. In this story, a villain who was actually introduced during the Galactus saga shows up and steals Ben's power for himself, leaving the Thing human once again.

Naturally, it's all an evil plot to take Ben's place with the FF so he can murder Reed Richards, but for Ben, it presents an interesting dilemma. When he returns to the Baxter Building as regular ol' human Ben Grimm, his teammates don't believe he's been turned back into his old self since they have "The Thing" standing right there. His choice, then, is to accept the price of no longer being a monster — losing his family — or try to regain the people he's closest to at the cost of what he's always seen as his humanity.

It's great stuff, and while it's the foundation of hundreds of similar stories that have cropped up in the Marvel Universe ever since, it's rarely been equaled.

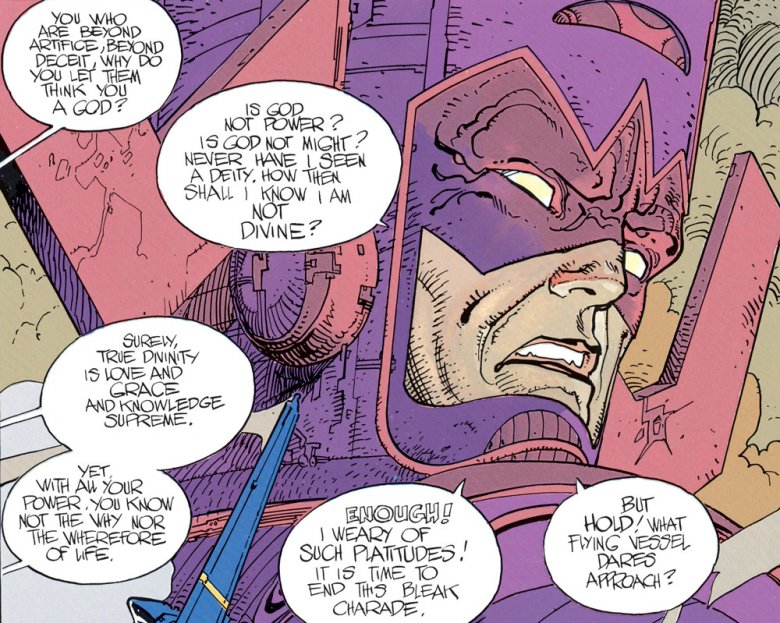

Parable (Silver Surfer #1 - 2, 1988)

On a technical level, "Parable" might be the single best comic book story Stan Lee has ever done. While his work with Kirby was defined by an energy that crackled off the page with excitement and adventure, this one has a level of craftsmanship that's staggering, and was largely responsible for introducing American superhero audiences to the legendary French cartoonist Jean Giraud, better known by his pen name, Moebius.

As the title implies, the story is essentially a parable, weaving downright Biblical themes of morality and free will into an intense and thrilling epic. It focuses on Galactus, descending to Earth with a plan for satiating his endless hunger: feeding on the worship of humans who see him as God. He declares himself to be divine, and commands humanity to cease all wars and violence, which seems like a good idea until you consider that his act of saving us from ourselves is built around worship and obedience under the threat of planetary annihilation.

That's where the Silver Surfer comes in, literally rising up from living on the streets — bundled up as a homeless person who just happens to also have a giant silver surfboard and the Power Cosmic — in order to confront Galactus and debate the nature of false divinity and whether Earth deserves the chance to make its own decisions, even at the cost of potentially destroying themselves through violence and cruelty. Throw in a famous evangelist who decides to declare Galactus the one true God, and his sister, who sees it all for the cosmic-scale scam that it is, and it's a truly amazing story.

In a lot of ways, it feels like Marvel's answer to books like Watchmen, jumping on the trend of using superheroes to tell "grown-up" stories, but I honestly think it holds up better than most entries in that genre. As befitting the idea of Stan's take on the Surfer as a cosmic pacifist, there's surprisingly little "action" in the story — aside from Galactus and the Surfer having a brief fight that levels a couple of skyscrapers — but every piece of it is compelling in a way that's decidedly rooted in superhero comics and allegorical sci-fi. It might take a little digging to find it, since it's been in and out of print in various formats ever since it came out in 1988, but it's well worth tracking it down, and stands as one of the high points of a pretty legendary career. In fact, I'd say it would be the high point, if it wasn't for...

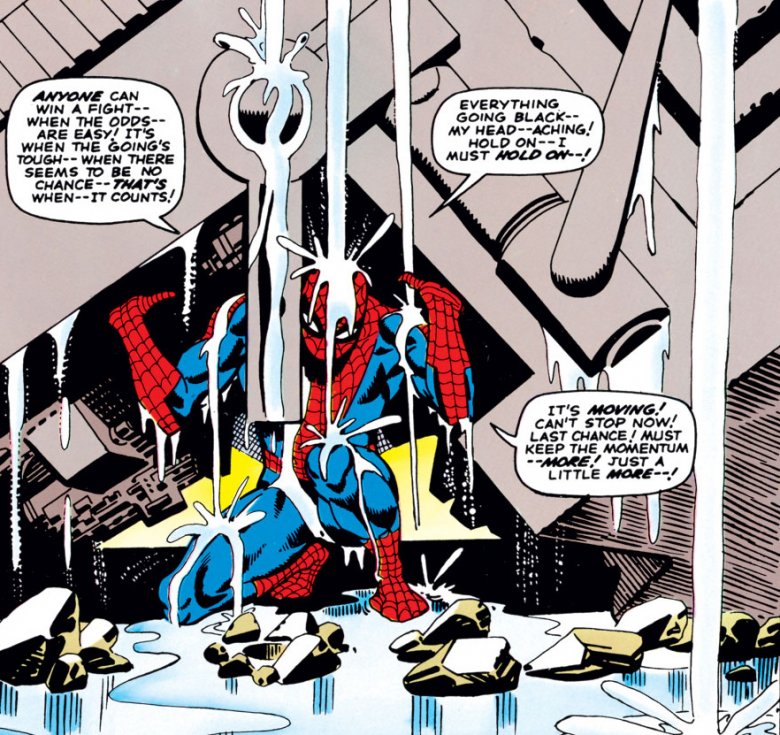

The Final Chapter (Amazing Spider-Man #33, 1966)

This is the greatest Marvel comic of all time, and arguably the single greatest superhero comic ever printed.

I usually refer to this one as "the one where Spider-Man does the thing," because it's such a foundational Spider-Man story — such a foundational superhero story — that even if you haven't read it, you know how it works. The hero is trapped after a pyrrhic victory, exhausted and beaten and being crushed under the literal weight of his enemies' machinations. He's at the end of his strength, and it would be so easy to just give up and accept his fate. And then, he can't. He has to fight, he has to keep going because there's someone out there who needs him, and he'll fight through figurative hell and literal high water to make things right.

It's the epitome of what Lee's sensibilities brought to the genre, the story that crystallized the idea that it's not that heroes don't get knocked down, but that they keep getting up. It's the same story that's been retold and iterated upon for decades, but this is the foundation, and its soaring, inspirational dialogue never fails to get me a little misty.

And that's just what's on the page. Something that's especially impressive is that when this comic was being made, Lee and Ditko's working relationship had deteriorated to the point where, according to Sean Howe's Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, they were no longer speaking to each other. The plot and staging are all Ditko, but that dialogue is Lee through and through, and stands even today as an all-time great.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."