That's What's Up: When The Punisher And Lois Lane Were Black

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: Since representation is such an important and delicate subject today, what can you tell me about those comics where the Punisher and Lois Lane were black? — @Ettore_Costa

Oh boy. You're definitely right about one thing, friend: this is indeed a delicate and important subject, and I want to go ahead and say right up front that as someone who looks an awful lot like that cartoon guy up there in the header image, I'm probably not the best guy to discuss it. If you're really curious about the nature and impact of these stories, particularly the Lois Lane one, you really ought to seek out work by critics of color, and especially women of color. I'd suggest starting here for that. The Punisher story probably requires a little less thoughtfulness, but, well, we'll get to that one.

That said, I am familiar with both of those stories, and I'll admit to being fascinated by them as bizarre little artifacts of their time. They're the kind of stories that would never — and should never — happen today, because when you get right down to it, they're about popular comic book characters engaging in what's essentially a weird, super-science version of blackface. But at least one of them kinda, sorta, almost had its heart in the right place to do it.

Lois Lane in: 'I Am Curious (Black)'

When it comes to this comic and its strange stranglehold on online comics discourse, I think Mike Sterling, who's been writing about comics for 15 years and selling them even longer, put it best. As he says, back in the old days of comics blogging — we're talking the mid-to-late 2000s here, so, you know, the ancient times — it seemed like every three weeks, someone would find this comic while digging through a back issue bin and have their mind blown. That makes a lot of sense, too: if there was one thing DC was good at in the '60s and '70s, it was making a cover that made readers need to know what was going on inside that comic.

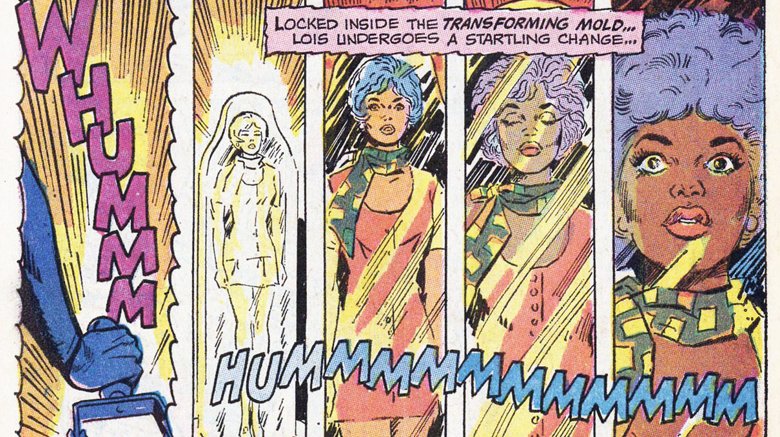

So let's go ahead and get that out of the way now. The story follows Lois Lane as she accepts an assignment to "get the inside story" of a Metropolis neighborhood called "Little Africa." When she finds that none of the black residents will talk to her — and that one even points to her as an example of "Whitey" — she decides to do the sensible thing and get her bulletproof alien boyfriend to use a science machine that he keeps at the North Pole to temporarily alter her appearance so she can go undercover. Perfectly logical.

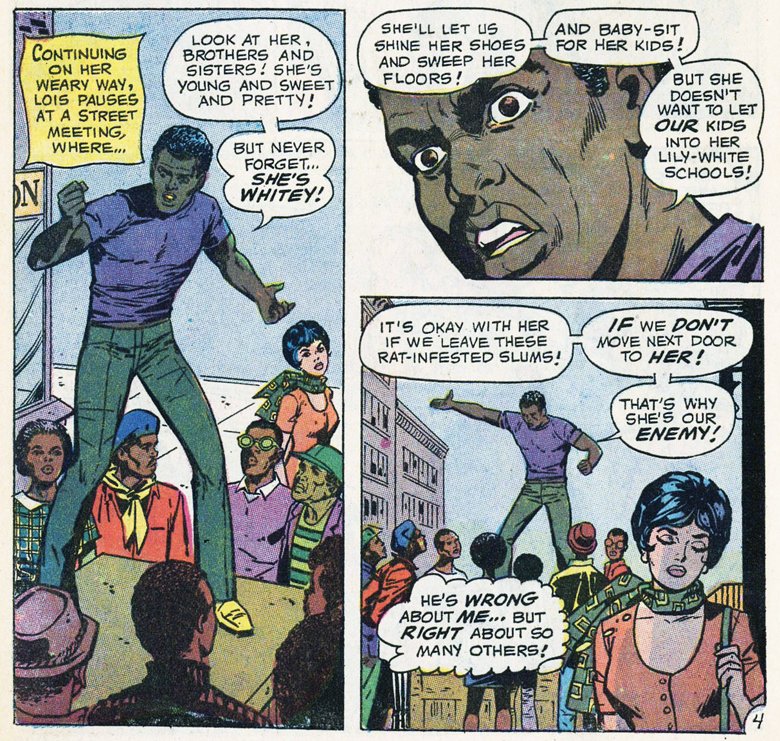

She does, and after exploring some of the surface-level, stereotypical problems of life as a black person — including being unable to hail a taxi and spending a page in a rat-infested tenement apartment — she runs across Dave Stevens, who is not to be confused with the guy who created the Rocketeer. He's a sort of community activist, and also the same guy who called her whitey before while lecturing neighborhood children about inequality. This time, of course, he's far more open, and they become friends. Unfortunately, they also stumble across a gang of (white) gangsters pushing drugs in an alley, and Dave is shot.

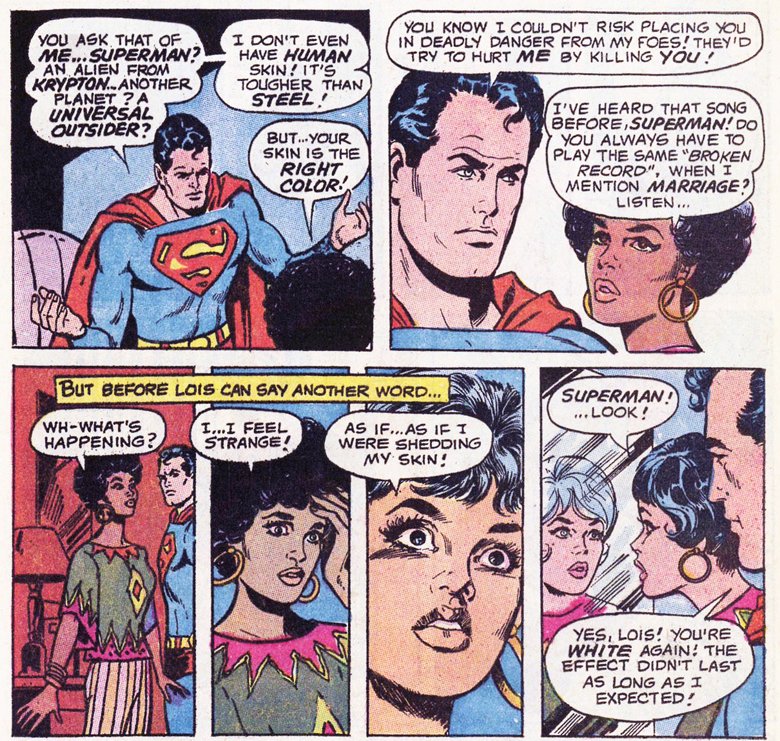

Superman shows up to take him to the hospital, but Dave desperately needs a transfusion, and the underfunded inner-city hospital is critically short on O-negative ... which just happens to be Lois Lane's blood type. She gives him a transfusion, which causes the Transformoflux machine's effect to wear off early. Dave asks to see her, and even though she enters as a white woman, he smiles, they shake hands, and, presumably, racism is ended forever.

Context and complications

Even 50 years later, it is a wild story, but there's a lot of context that often gets lost when we look back on it, both in comics specifically and in the larger culture. And the biggest bit of contextual influence has got to be the time that this same setup basically happened in real life.

When they created this story, Robert Kanigher, Werner Roth, and Vince Colletta — who, it will not surprise you, were all white dudes — were undoubtedly inspired by John Howard Griffin's Black Like Me. Originally released in 1961, that book chronicled Griffin's journey through the American south as a white reporter who had literally undergone medical treatments in order to temporarily darken his skin. In his case, there wasn't a Transformoflux Plastimold, just a lot of ultraviolet light and heavy doses of a drug called methoxsalen.

Black Like Me was both a commercial success and an important social touchstone. It was built on the idea that white audiences would only accept and understand the consequences of racism if it was related to them by a white author who had experienced it firsthand, and while it's pretty unfortunate that this notion turned out to be true, it worked. As Gerald Ealy wrote, "Black Like Me disabused the idea that minorities were acting out of paranoia," and, maybe equally important, allowed Griffin to confront and acknowledge his own racism.

That's a crucial element that, perhaps unsurprisingly, Lois Lane never actually gets around to. In fact, when Dave is talking about how minorities are exploited by whites who are happy to reap the benefits of their labor, she specifically says "he's wrong about me, but right about so many others!" That makes sense, though. Even if Kanigher had wanted to have Lois explore her own bias — and given his pretty spotty track record on the subject of race in superhero comics, it's unlikely that he did — an issue of Lois Lane where Superman's Girl Friend examined her own internalized white supremacy probably would've been a hard sell for the editors.

Slightly slower than a speeding bullet

The other relevant context of this story has to do with what was going on in comics at the time. In 1970, a year after the Batman TV show and its studiously campy silliness went off the air, DC was desperate to make their books seem more "grown-up" and socially relevant — which might be why this one was named for a Swedish art film that was banned for pornographic content. It's not a coincidence that this Lois Lane story hit newsstands the same year Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams put out the Green Lantern/Green Arrow series that famously dealt with topics like drug addiction and, of course, race in America. Which was particularly relevant given that comics were finally starting to change.

It's worth noting that while black creators had been working in the industry since its inception, the superhero genre didn't get its first black superhero — Black Panther — until 1966. Even then, he didn't move onto a starring role, in Jungle Action, until 1973, about a year after Luke Cage made his debut in Hero For Hire #1 in 1972. DC was a even slower to get around to it, giving John Stewart a Green Lantern ring in 1971, and then finally launching their own headlining black hero in 1977 with Black Lightning. The nice thing about all this is that it speaks to a genuine desire from the creators and publishers to correct a longstanding oversight — if only because they realized that there was a lot of money to be made with it.

But isn't the real problem that people are mean to Lois? (No.)

While tackling social issues worked pretty well for characters like Green Lantern (and across the street with Spider-Man, among others), bringing them up in Superman books presented a weird sort of problem. It's most prevalent in the landmark "Must There Be A Superman?" story from 1972, where Elliot S. Maggin and Curt Swan asked Superman what would happen if he "rebuilt every ghetto and arrested every slumlord." The thing is, in his case, that's not a philosophical question, it's a practical one. He actually could do all of that, but a story that deals with social issues pretty much requires you to not actually completely eliminate them in the span of 17 pages if it's going to have any actual relevance to the real world.

That bit of weirdness rears its head again in this story. In order to get to the ending with the blood transfusion, Dave has to get shot even though Superman is following Lois to keep her out of trouble. It stretches the story, and it's especially noticeable because literally the first thing we always hear about Superman is that he's faster than a bullet.

But that's just a contribution to the larger problem with this one. I honestly think Kanigher and company had their hearts in the right place, and if nothing else, they do take a moment to point out that it's really easy for Superman, as an alien, to be accepted into American society because he has the luxury of being able to pass as a white (human) man. Unfortunately, they wound up with a story that feels patronizing, especially since it turns into a literal white savior narrative by the end. The actual problem in this story, the one that's solved in the climax, isn't racism, it's Dave's mistrust of Lois and that he doesn't know she's a Good White Person. The character we're meant to sympathize with isn't Dave, whose anger at Lois is presented as completely unfounded ("he's wrong about me"). It's Lois, who doesn't understand why the residents of Little Africa won't just open up and trust her. That's a rough direction to take that story, and misses the point of doing it at all. Again, I think they had good intentions, but we all know which road is paved with those.

I Am Punisher (Black)

This Punisher story, though... Folks, I don't know what the intentions were behind this one.

The context for this 1992 saga is a little easier to get through, at least in terms of how it plays out on the page. It's actually the final arc of the ongoing Punisher series written — or in this case co-written — by Mike Baron, who had been on the book since it kicked off five years before. The thing is, it's pretty clear if you go back and read it that it wasn't meant to be that way at all. Instead, Baron's final arc seems like it probably should've been the one before.

The story that immediately precedes it is literally called "The Final Days," and it's about as much of an action-packed ending to a Punisher series that you could ask for. It's a seven-part arc from an era when comics still rarely dove into multi-issue stories, and involves Frank Castle having all of his secrets revealed to the mob and then being arrested and sent to prison. That had happened before — it's actually the subject of the first Punisher series, Steven Grant and Mike Zeck's "Circle of Blood" — but this time, the consequences felt a lot more dire. The prison sentence turned out to be a setup to get Frank confined in a place with a couple hundred people who were willing and able to murder him, and his old enemy Jigsaw carving up Frank's face with a shiv to give him a set of irreparable scars that matched Jigsasw's own.

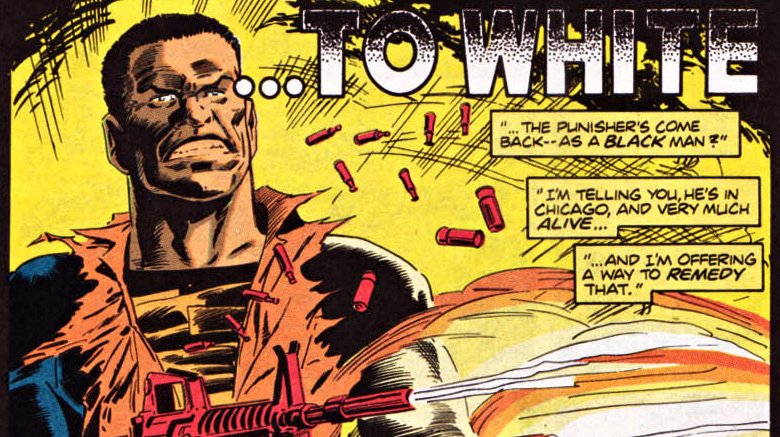

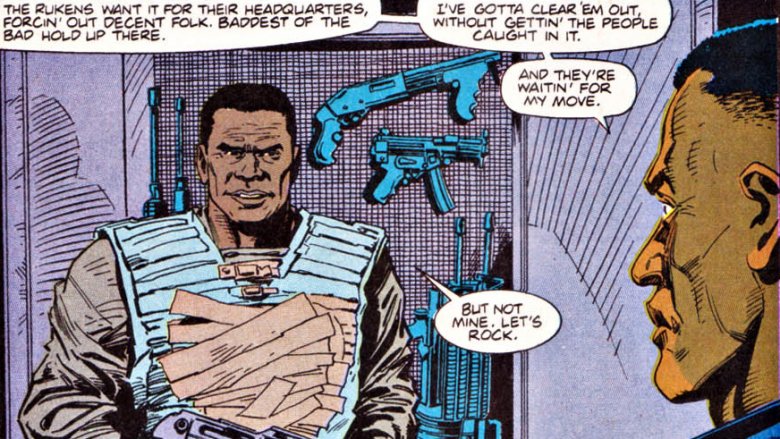

So here's where it gets weird: Frank busts out, of course, and is then taken to a disgraced former surgeon who developed a heroin addiction and became a sex worker, but who also happened to be a pioneer in an experimental plastic surgery that involved the skin pigment melanin. When he wakes up, his scars are gone, his skin is darker, and the doctor's buzzed his hair down to a fade.

Enter: The Man Called Cage

One thing that's always stuck out to me about this story is that for the most part, Baron's run on Punisher worked largely because it felt like Baron was just dropping Frank Castle into whatever VHS tape he'd rented from Blockbuster that week. There was a story where the Punisher went undercover as a high school substitute teacher that was pretty much just the Marvel Comics version of Class of 1984, another that seems like a riff on Stone Cold where the Punisher went undercover in a biker gang as a meth cook named "Freewheelin' Frank," and enough American Ninja-esque stories to match the entire Cannon Films ouvre. If it was a schlocky mid-'80s action movie, then there's a good chance there's an equivalent story in the pages of Punisher. This one, though...maybe Blockbuster got in a copy of Soul Man that month.

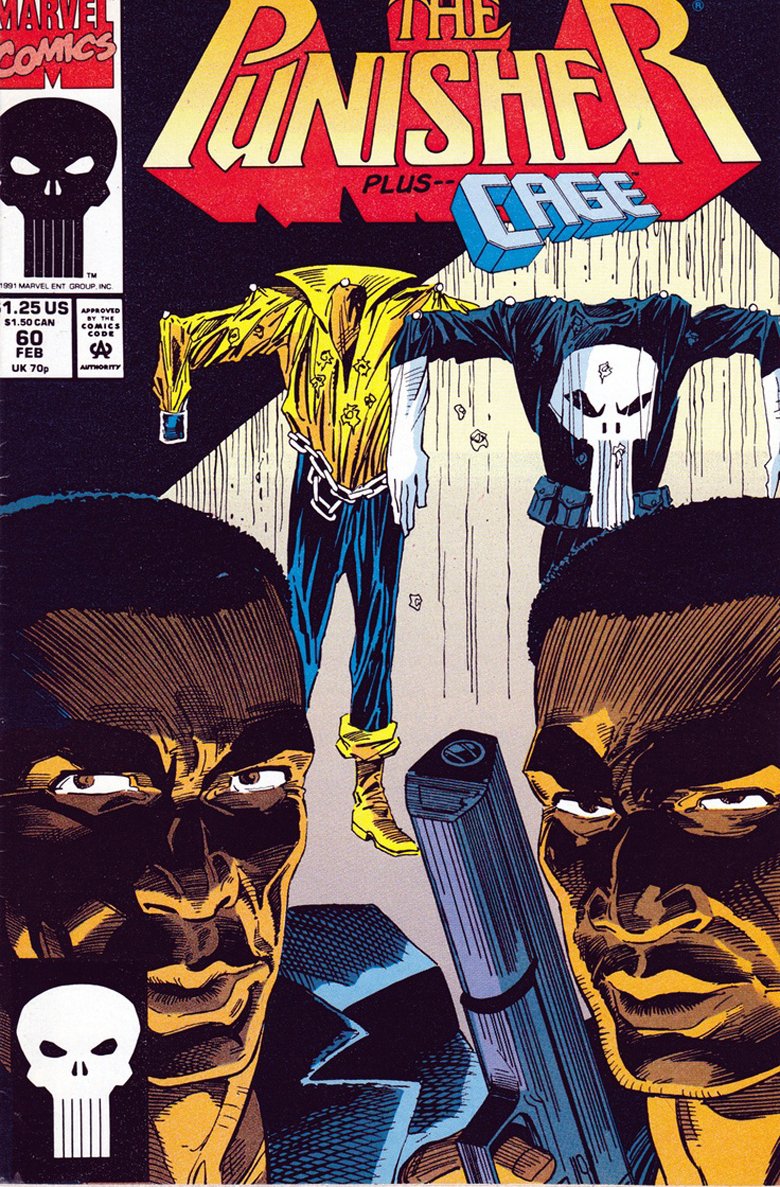

As the story goes on, it becomes apparent that this particular series of unfortunate events was less about getting out of the narrative hole that had been dug with "Final Days," and more about providing some cross-promotion for another new Marvel series. In this case, it was Cage, the new Luke Cage title that was launching around the same time — the Punisher team-up would start in February, and Cage #1 hit stands in April that same year.

That actually made sense, too. At the time, Punisher was one of Marvel's hottest franchises, holding down three monthly titles and even shipping twice a month during summers. The relaunched Cage would be built around a similar urban crime aesthetic, but with a superheroic twist: Luke Cage was relocated from New York to Chicago, with a newspaper hiring him to be their in-house superhero so they could cover his crime-fighting exploits.

The actual story title: 'Fade to White'

What doesn't make sense is that someone, somewhere, had the idea that if the Punisher was going to team up with one of Marvel's most prominent black superheroes, he should also be black for three months while it was happening. And I say "someone" because it's still a mystery as to where the idea came from; when I wrote about this comic years ago on my own blog, Baron showed up in the comments to say that he was, and I quote, "just following orders."

To be a little more fair than this story deserves, the creators do make an attempt to justify Frank's "disguise." There's a plot point about how he's laying low while the Kingpin and other mobsters hunt him, and the side effect of the melanin treatment made for a pretty effective disguise. They commit to the bit as far as having Frank cover up the giant skull logo on one of his kevlar vests with duct tape so no one will notice he's the Punisher. Considering this is a dude who once took the time to paint a skull on his chest in axle grease when he couldn't find a shirt so everyone would know who was killing them — Punisher #48, if you want to look it up —that's a surprising amount of restraint.

Really though, that's just the plot making a lengthy reach to justify its own bizarre choices. The good news is that the story tends to lean into its near-mindless shoot-'em-up action, but when it does make an attempt at dealing with more serious issues of race, it's predictably clumsy. While I've read both of these issues before, today marks the first time that I've read them back-to-back, and it's surprising and a little depressing that two comics printed 20 years apart both present the same views, beat for beat, of life in the inner city.

Outlaw

There is one more interesting wrinkle to the Punisher story, though. I'm honestly not sure if Marvel was using this particular story to both promote Cage and test the waters to see how fans would react to actually having a black Punisher, but only a few issues later, they managed to introduce exactly that sort of character.

It happened in a seven-part story called "Eurohit." As the title implies, it's basically the Punisher taking a very murderous trip through Europe, and when he stops off in England in the first part, he meets a new character: Nigel Higgins, also known as Outlaw. He was essentially the Punisher's #1 fan, and after losing his own family to crime, styled himself as the British Punisher, even going as far as incorporating Frank's signature skull into his own logo.

Despite the story potential of a black Punisher-style vigilante operating out of London, nothing ever really happened with Outlaw. A few years later, he showed up in a story along with Lynn MIchaels (a.k.a. Lady Punisher) and a couple of other ersatz Punishers, but after that, he was absent for about 20 years.

But then he showed up as a main character in Contest of Champions, and among other pretty great moments, revealed that he'd given up on killing people in favor of helping them. Starring in an ensemble cast tie-in to a mobile game might not be a slot in the Avengers, but it's one of the best hidden-gem comics that Marvel's done in recent years, and is well worth checking out. If nothing else, nobody dyes their skin in order fool someone into thinking they're a different race, and at this point, I'm willing to accept that goes a long way.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."