Coraline's Journey From Novella To Animated Classic

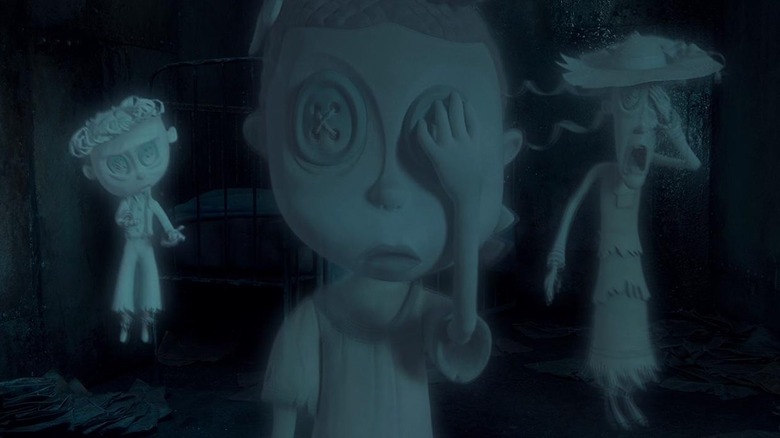

The first feature film released by stop-motion animation powerhouse Laika, "Coraline" was unleashed upon the world in 2009. An adaptation of Neil Gaiman's dark fairy tale of the same name, "Coraline" follows Coraline Jones, an imaginative girl bored with her new home and her workaholic parents. One day, she discovers an alternate reality that looks a lot like her real life ... only much, much better. But as the predatory nature of her counterfeit parents begins to emerge, Coraline realizes that she's only the latest kid to fall prey to this enticing trap.

Over a decade after its initial release, "Coraline" persists as a modern classic. It's an excellent example of an all-ages film that never speaks down to or insults the intelligence of its young audience. It's also visually gorgeous: Stop-motion animation has never looked more beautiful than it does in "Coraline," where luminous carnivals, sumptuous night gardens, and slinking cats collide. How did this fantastic film come to be? We're here with all the answers. This is how "Coraline" went from being a beloved novella to an animated classic.

Neil Gaiman and Henry Selick are fans of each other

Not all novelists have the luxury of liking the directors who adapt their work. But "Coraline" author Neil Gaiman was already a fan of director Henry Selick's work when the adaptational process began — and vice versa. "I loved 'The Nightmare Before Christmas' and Henry was just on my radar as such an interesting talent," Gaiman gushes on the film's DVD bonus features. "I was introduced to Neil before 'Coraline,' his book, was even finished," Selick explains. "And [Gaiman] said he thought of me as a possible director; as someone to help turn it into a film."

According to Gaiman, Selick was immediately on board. You really get the impression from the way Selick and Gaiman speak about each other's work that they each think highly of the others' creative decisions. "The number one thing was to respect the story of the book and the tone and flavor," Selick explains, "and to try and hold onto that no matter what we needed to do to change it." Clearly, this approach worked.

Tadahiro Uesugi's influence

As director Henry Selick explains on the "Coraline" DVD's making-of featurette, when it came to designing an overall look for the film, the goal was to move away from what was popular in Western animation at the time. For reference, when "Coraline" went into production, animated features like "The Polar Express," "The Incredibles," and "Shrek 2" were dominating the landscape. In sharp contrast to these films, Selick drew inspiration from Japanese illustrator Tadahiro Uesugi, who, in a roundabout twist of fate, is himself heavily influenced by American advertising illustrations of the 1950s.

"There was just something elegant and pure and simple about his work that I responded to," Selick explains. "And what I love about it is that it goes to this really bold place. He takes a risk. He doesn't just creep up towards something interesting. He goes to it immediately." A quick glance at the artist's vivid work makes this immediately clear. "Coraline" art director Tom Proost concurs: "Tadahiro's influence was huge. It was pretty much his illustrations that Henry fell in love with and that all of our illustrators [were] asked to work off of."

Coraline determined Laika's future

"Coraline" was the first feature film released by Laika Studios. As detailed by Animation Magazine, The stop-motion powerhouse's story began in 2005, four years before "Coraline" premiered. From today's vantage point, it's clear that "Coraline" was an early sign of the studio's incredible artistry. Later features like "ParaNorman" and "Kubo and the Two Strings" feel like logical extensions of everything that makes "Coraline" so special.

But back when "Coraline" was new, it wasn't clear if Laika's creative gamble was going to pay off. A 2009 article from Willamette Week Online vividly captures the anxiety of this era. In the slim slice of time between production on "Coraline" wrapping up and its actual premiere, the studio's future was a giant question mark. Proposed follow-up features were put on the shelf and Laika employees — some of whom had moved their entire lives to Portland — were basically left holding their breath as they waited to see how the movie would do. They were also waiting to see if Nike co-founder Phil Knight, a major investor in the studio, would deem "Coraline" enough of a success to push forward. Luckily for cinephiles everywhere, "Coraline" was a hit and Laika did, indeed, move on to new projects.

The live-action Coraline that wasn't

Though rumors of a live-action "Coraline" remake emerged in 2019 (and were quickly squashed as nonsense) it's very hard to imagine the story without its signature stop-motion. The movie's hand-made aesthetic feels utterly integral, especially in how it immerses audiences in the nightmarishly charming Other World.

That said, as director Henry Selick specifies in the film's commentary track, "Coraline" was originally conceived as a live-action project, with Dakota Fanning tapped to portray the titular girl on-screen, rather than provide a vocal performance. This briefly-considered approach had a lot less to do with creative choices than with studio contracts. When Selick initially approached Bill Mechanic to produce "Coraline," there was a conflict involving an output deal with Disney, which stipulated that the movie couldn't be animated. But Selick felt that a live-action "Coraline" would be way too scary. In the end, as The Columbus Dispatch bluntly put it, "Selick's push for animation prevailed."

Book versus movie

As with any book-to-screen adaptation, "Coraline" deviates from its source material in a number of ways. The most notable is that the story is set in the United States, rather than England — though "Coraline" definitely deserves credit for including a couple of Brits in the forms of Miss Spink and Miss Forcible. Another large change is the addition of Wybie Lovat, a local kid who is both a pal to Coraline and an integral part of the Other World's intrigue. As Neil Gaiman explains in the film's making-of featurette, Wybie's presence makes a lot of sense. Not only does he give Coraline someone to talk to, he pads out what would otherwise be a much shorter film.

Fans of the book can likely spot a slew of other changes. In the book, Coraline's hair is black, not blue, and the performing rodents are rats, rather than jumping mice. There are also many more frightening sequences in Gaiman's text, including a nightmarish to-do with the Beldam's severed hand and a chase sequence in which the Other Father is reduced to a doughy flesh blob.

The importance of Coraline's hair

As character fabrication supervisor Georgina Hayns emphasizes in the "Coraline" making-of featurette, perfecting Coraline's hair was a major creative goal. While the puppets' bodies were moved through the use of armatures (metal skeletons), Coraline's hair was manipulated through the complex layering of super glue, prosthetic glue, and very tiny wires. This allowed the team to animate her various wigs frame by frame, with incredible precision.

"We have to make sure that almost every hair is pretty much controllable," explains Suzanne Moulton, the lead hair and fur fabricator on the film. While other characters' hair was made out of everything from horse hair to human hair, Coraline's wigs were completely synthetic. This enabled a whole new level of expressive movement. Fans of the book might find this especially interesting, as the Other Mother's hair undulates as if it were underwater in Gaiman's text. No wonder Coraline is quicker to catch onto the Beldam's evil shenanigans in the book.

Perfecting the characters' costumes

Coraline has a seriously impressive wardrobe. From her starry sweater to her matching pajama set, everything she wears looks adorable, comfortable, and like something a kid her age would actually wear. This is all thanks to the costume department. All of the movie's clothing was made by hand: Silk night slips were strenuously sewed, wool sweaters were knit with exacting hands, and rhinestones had to be applied with surgical instruments, to ensure the utmost precision.

The amount of effort and detail that went into making these itty-bitty garments was only outdone by the amount of work that went into ensuring they fell naturally on the puppets' frames. As the making-of documentary on the DVD details, padding was used to make sure that the clothing wouldn't sag. Moreover, all of the costumes had to be manipulatable, with wires and armatures sewn in to allow the clothing to both hold its shape and be moved by animators. If you really want to have your mind blown, pay attention to all the rivets, zippers, and buttons the next time you watch "Coraline" — they were all made by hand!

Bringing the gardens to life

As art director Matt Sanders emphasizes on the film's making-of featurette, while the gardens only account for five minutes of screen time, they took multiple months and 15 sets to create. The team responsible for bringing the gardens to life had to come up with a number of creative solutions when it came to animating the otherworldly flora. When tasked with creating a shot in which dozens of blue flowers sprout up before Coraline's eyes, this talented group created a handful of animatable blue blooms, which they surrounded with mirrors. This provided the visual effects department with a number of different perspectives on the same flower's animation, allowing them to create complex composite shots.

This wasn't the only place where the garden team thought up clever approaches to complex scenes. To create the flowers' bioluminescence, the animators combined plastic mesh, fiber-optic cables, and flashlights. Other tricks, like shooting sequences in reverse to give the impression that things were growing, allowed them to create mesmerizing motion.

A soundtrack full of wonderful nonsense

One of the most striking (and, let's be honest, scary) parts of "Coraline" is its haunting soundtrack, which comes courtesy of Bruno Coulais. In a 2009 interview with Ain't It Cool News, director Henry Selick explained that Coulais' sound captures both the whimsy and fright of childhood, both of which are key to "Coraline." Indeed, Coulais made use of children's choirs and soloists on the film's soundtrack. Amazingly enough, the main soloist's name was Coraline.

If you've ever strained your ears and racked your brain trying to figure out what language the choir is singing in, you're not alone. But in fact, the choir is singing nonsense. "You might hear a little accent," Selick clarified, "and you're not sure, but that's something Bruno likes to do. He uses sounds. It's all sung nonsense." This nonsense is so wonderful, it earned Coulais an Annie Award.

The hidden meaning of Mr. Bobinsky's medal

Sergei Alexander Bobinsky is Coraline's Russian neighbor. Everyone agrees that he is incredibly weird. Coraline is of the opinion that the man is mentally disturbed, while her mom, ever the bummer, assumes he's just drunk. To be fair, Mr. Bobinsky doesn't look like a picture of perfect health. His complexion is a grey-blue hue, while his extremities are a sickly violet. His gangly body is also disproportionate, and his eccentricities belie an underlying strangeness that often eclipses his kindness.

Before you dismiss Mr. Bobinsky as nothing more than a weirdo, pay close attention to the medal on his chest. As one keen-eyed Redditor noted, Mr. Bobinsky's medal isn't just any old medal — it's a ЧАЭС medal. This reveals that Mr. Bobinsky was a Chernobyl liquidator, who participated in the clean-up of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant disaster. As you might imagine, being on the front line of a nuclear catastrophe wasn't exactly great for the liquidators' health. But happily, Mr. Bobinsky is still kicking, even if he is a bit of an oddball. His medal is probably one of the movie's coolest details, and one of the easiest to miss.

Coraline made use of 3D printing

Ever since 3D printing hit its stride, the innovative technology has churned out all manner of things, from entire houses to prosthetics for animals and humans alike. As Laika's director of rapid prototype Brian McLean explains in a featurette, the animation studio is hip to this new wave of artistry: The "Coraline" team made use of 3D printers for facial animation. "When we were building 'Coraline,'" McLean details, "one of the things that was limiting us at the time was the fact that we were having to hand-sculpt each individual face." With the help of 3D printers, the folks at Laika were able to create detailed facial expressions without bloating production costs.

Animators were able to further expand puppets' expressive ranges by splitting faces into top and bottom halves (the connecting seam was removed digitally, in post-production). These pieces were printed on a white material, which was tweaked by artists (Laika would take a risk and switch to color 3D printing in their next feature, "ParaNorman"). The result was a massive library of facial expressions that allowed the animators to achieve subtle and varied movements.

Even Coraline's digital elements were handmade

While "Coraline" is emphatically handmade, the film does incorporate some digital elements. One particular technique, digital compositing, was actually used to further the film's dedication to practical effects. As explained in the film's making-of featurette, some visual aspects of "Coraline" could not be completed solely using stop-motion. One example is the fire in the fireplace, where we see a doll shrivel up and burn. While the flames were composited digitally and tweaked in Photoshop, each lick of fire was hand drawn.

Similarly, the rolling fog was created with dry ice, which was digitally composited into each shot. In the DVD featurette, the senior compositors recall using air cannons to manipulate the fog into matching the character's shoves and footsteps. The desire to make everything in "Coraline" look like it'd been touched by human hands offers a unique sort of charm, and required some truly impressive techniques that span new and old technology.

An actual lunar eclipse served as inspiration

While there's a lot of charming, creepy, and charmingly creepy things vying for your attention in "Coraline," viewers doubtlessly take note of the moon. Not only is the moon freakishly large in "Coraline," the celestial space rock serves an important storytelling role. When our intrepid heroine is in the Other World searching for the ghost children's eyes, an ominous shadow gradually spreads across the moon's surface. It depicts a ticking clock counting down the hours Coraline has left to free the captured children. The ending of "Coraline" is filled with intense plot details, visuals, and conflicts, but this is definitely one of the most vivid.

As if there weren't enough reminders of the film's most horrifying motif, the shadow gradually creeping across the moon's surface is — you guessed it — a big button. But lest you think that the button moon eclipse is just a creepy creative decision, listen closely to the director's commentary. There, Henry Selick specifies that the inspiration for this moon was a real lunar eclipse that took place during production. How loony is that?

The Other World was designed with 3D in mind

On top of being a book-to-screen adaptation and a risky stop-motion feature, "Coraline" also had to balance the public's reinvigorated interest in 3D. To put things into context, remember this: James Cameron's "Avatar" came out the same year. As revealed in the film's making-of featurette, the filmmakers behind "Coraline" took advantage of this in a unique way. They created the illusion of depth with a tried-and-true method known as stereoscopy.

To make a long story short, stereoscopic illusions work on the basis of presenting a 2D image to the left eye and a 2D image to the right eye, which creates an artificial perception of depth. To achieve this effect, the team at Laika built an automatic rig that took two separate shots (one for the left eye and one for the right eye) at the same scale as the puppets. As anyone who's seen the movie can attest, this approach pays off. Furthermore, as director Henry Selick specifies in the film's commentary, the team deeply considered the potential narrative impact of 3D. This was especially important when creating the real world and the Other World; the latter realm was intentionally designed to feel less flat.