That's What's Up: Terrible Ideas That Actually Turned Into Awesome Comics

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: What are some of the "worst ideas ever" in comics that wound up being great in execution? — @jdstarns

Here's a secret that nobody really tells you about creating comics: you don't actually need to start with a great idea. Don't get me wrong, they're certainly nice to have, and a lot of the superheroes you think about have their roots in some solid premises. Superman, for instance, is a great idea, and while the original idea behind Batman was just wholesale ripping off the Shadow, putting your own spin on something that's already a success is a pretty solid strategy when your entire medium is just getting its start.

That said, a "good idea" isn't exactly necessary. With enough effort behind it, even the goofiest, most counter-intuitive premise can work—and we know that because the history of comics is full of stories and characters that should never have been as good as they were.

Spider-Man: the ultimate bad idea

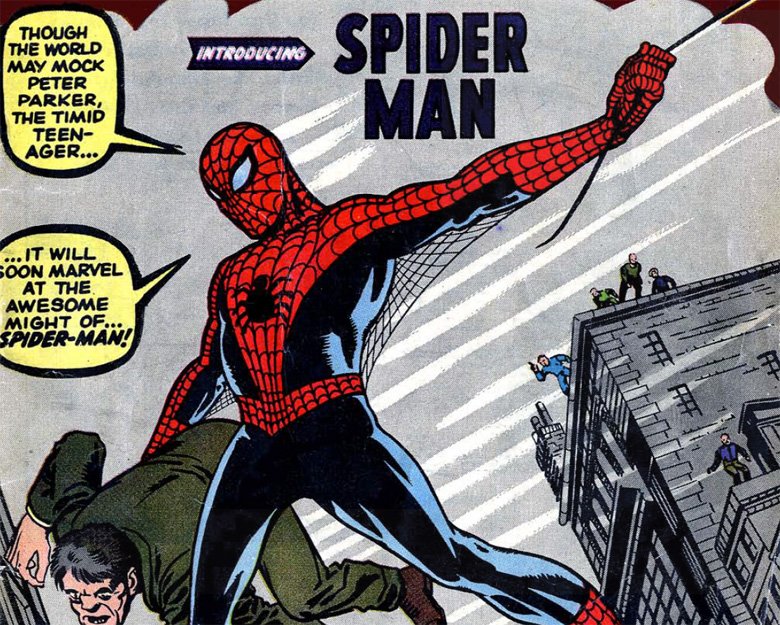

Maybe the best example ever of a truly awful idea that resulted in one of the best things ever was, of course, the Amazing Spider-Man. He's quite possibly the single greatest creation in the history of comics, but literally nothing about him should work at all.

Even the basic idea is bad—or at least, it seems like it would be. As you might expect, Stan Lee has done countless interviews about the creation of Spider-Man, and in addition to always saying that he thought it would be "groovy" if someone could swing around on webs, he's mentioned the difficulty in pitching the idea to Marvel's publisher, Martin Goodman. His argument was pretty simple and, to be honest, pretty bulletproof, too: people hate spiders.

Admittedly, people aren't really that fond of bats, either, and the competition was doing okay with a hero based around that idea. The difference, of course, is that bats at least had that history with Dracula, lending a pop-cultural connection to another character who would haunt the night terrifying those who opposed him. Spiders, on the other hand, had no such connection. Well, unless you count Charlotte's Web, which was originally published in 1952. Even then, the spider had to learn to write in English, hand out a ton of compliments, and die in order to get people to actually like her. Peter Parker didn't even have that.

Peter Parker, the spectacularly terrible person

Even without the difficulties of the premise, though, Spidey was a hard sell. By the time he debuted in 1962, Marvel had already had some success introducing a new kind of superhero that stood in contrast to established characters like Superman, but the Fantastic Four were still pretty admirable characters from the start. In addition to being daring amateur astronauts, Reed was a square-jawed Atomic Age super-genius, Johnny was a cool hot-roddin' teen, Ben was a tough, never-say-die fighter pilot, and Sue was ... well, it took them a few years to get around to actually giving Sue a character, but they got there eventually.

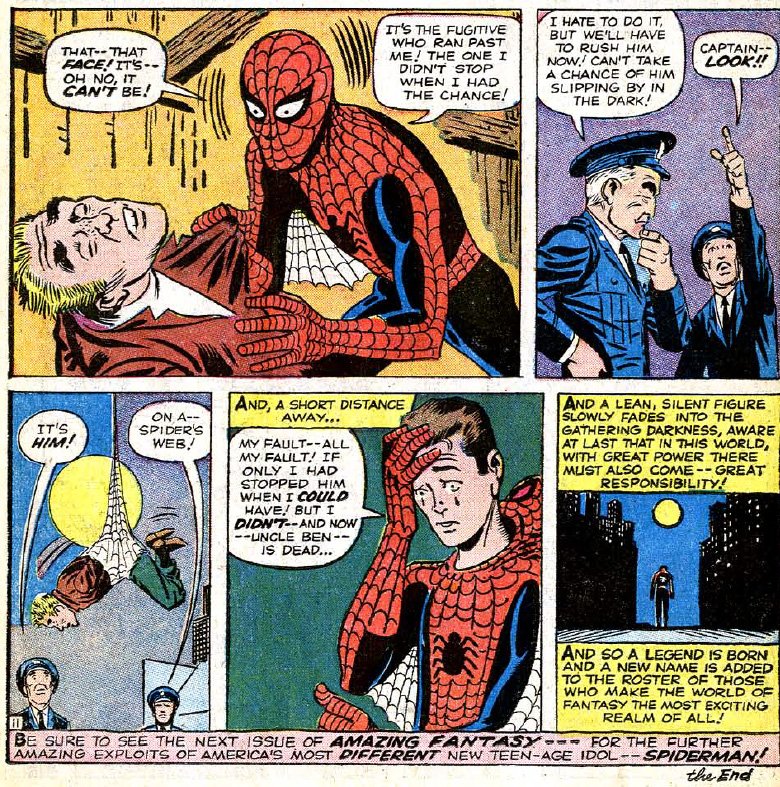

Peter Parker, on the other hand, starts his career as the opposite of a power fantasy. As much as nerdy readers might've been able to identify with the picked-on kid who excelled in school but had difficulty making friends, he's not exactly an aspirational figure. Ditko draws him as, well, a teenager, all uncomfortable angles, giant glasses, and stooped shoulders. Even after he gets powers, he's a jerk about it—the first thing he does is publicly humiliate someone who was stronger than he used to be, and then he immediately starts making money with his powers.

That, of course, is the entire deal with Spider-Man's origin, and that whole thing with power and responsibility that comes up quite a bit whenever he gets a little mopey about Uncle Ben, which is all the time. But that original story ends with the lesson, serving as this weird blend of superhero story, morality play, and EC style ironic-twist horror comic. If that's all there had ever been, and given that Spider-Man made his debut in the final issue of the Amazing Fantasy anthology at a time when the original Bullpen was throwing whatever they could at the wall to see what would stick, there's a good chance it would've been, you wouldn't have to do a lot of digging to figure out why it failed.

Instead, it all clicked, partially because readers found that new kind of storytelling compelling, and partially because Lee and Ditko were a couple of truly amazing comics creators who were quite literally revolutionizing comics with every single story.

The Dark Knight Returns

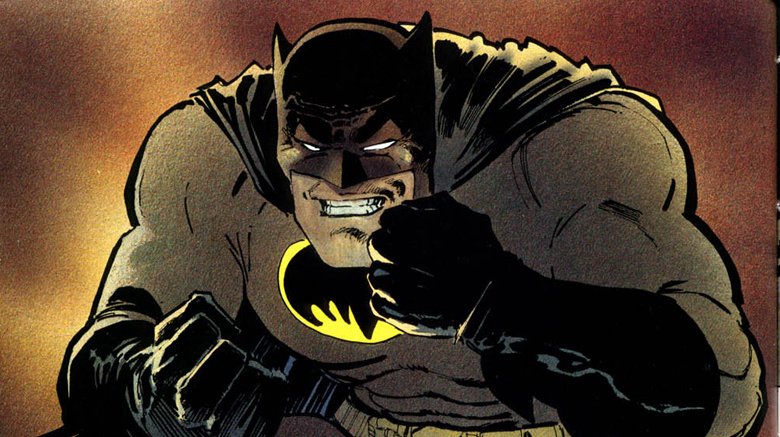

The other big, obvious one has to be Frank Miller's classic The Dark Knight Returns, if only because it's the platonic ideal of the Grim 'n' Gritty Take done for all the wrong reasons.

To be fair, it doesn't actually seem like it's that much of a departure from the norm, partially because virtually every Batman story in the 30+ years since has existed in its shadow. Even at the time, the Batman books had been steadily moving in a darker direction ever since 1970, and while DKR was certainly a huge leap forward, it was a leap that seemed logical given the trend. The thing is, those books were all reacting to the same thing: the 1966 Adam West Batman TV show. That's the context that makes the book work, that the Gotham City depicted there was the '60s pop-art metropolis of the TV show had decayed into the urban crime-wave nightmare of the mid '80s.

In his introduction to the paperback version of DKR, Frank Miller talks about how one of his primary motivations for doing the story was finding out when he turned 30 that, since Bruce Wayne was meant to be an eternal 29, he was actually older than Batman. His solution was to create a story where we caught up with the Batman of the '60s 20 years later, after his retirement, when the world had moved on from colorful arch-criminals to spree killers and cartoonish street gangs.

That's the actual premise of that comic: creating an old Batman so that the creator can feel young again, and setting him in a world that shows that his heroics were ultimately pointless in keeping the city safe from The Real Problems, underlined by going way dark and even hinting that the very act of being Batman could result in Robin being murdered. That's a rough premise, even for a time when the superhero genre was desperate to be seen as "grown-up." And yet, Dark Knight Returns was a huge success, and despite three decades of imitators and critical examination that have taken the bloom off the rose, is still agreed on as one of the better comics of that decade.

No Man's Land put Batman into Mad Max times

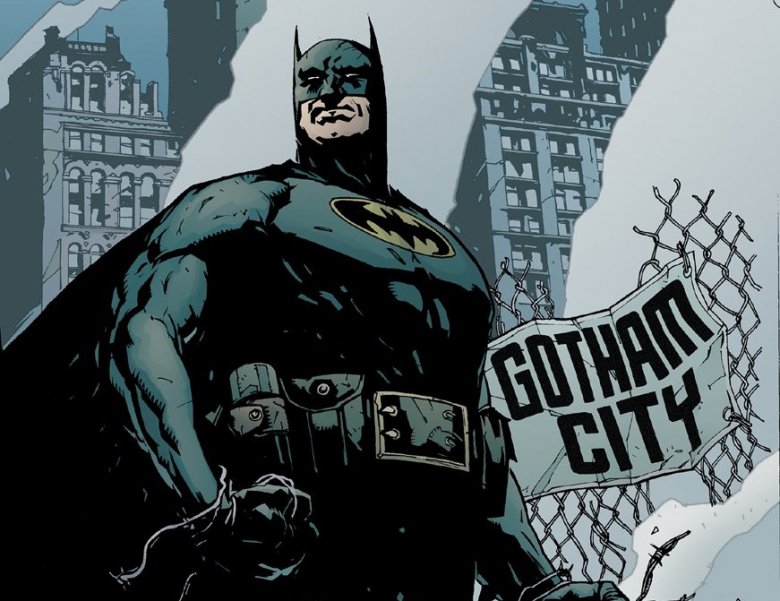

Now that I'm thinking of it, there's another Batman story that, in theory at least, is rooted in a premise that should not work at all: No Man's Land.

The pitch reads like a checklist of bad ideas: it's a full year-long story arc running as a weekly story through all the Batman books, plus additional tie-ins from the rest of the Batman Family and books like JLA (check!) that doubled down on these devastating, high body-count events like Contagion, Legacy, and Cataclysm that everyone was already tired of (check!), in which Gotham City was completely destroyed (that's a big check!) by an earthquake that Batman was powerless to stop (check!). Instead, the government abandoned a major American city along the lines of New York, leaving it as a lawless ruin overrun by gangs led by supervillains and cops, a premise that stretches believability even in a world where superheroes exist (check!).

In practice, though, it was exactly the shot in the arm that the Batman books needed in 1999. As ridiculous as that premise might be, the idea of basically doing post-apocalyptic Batman turned out great. It gave his adventures a whole new context, and taking the disaster-movie storytelling of the previous few years to its logical conclusion allowed creators to clear the board and, once Gotham City was inevitably rebuilt, allowed the creators to focus on a sort of "back to basics" approach to crimefighting without feeling like they weren't living up to the consequences. There are plenty of missteps, sure—and Batman editor Denny O'Neil devoted a whole chapter to The DC Comics Guide To Writing about the hassles of doing a "mega-series" that juggled so many creators on a tight schedule—but it works amazingly well.

It's so good that even the novelization is worth reading, and might actually be better than the comics. That's actually not too surprising, though, since it was written by Greg Rucka. At the time, he was primarily known as a novelist, but broke into DC during NML and quickly became one of the most lauded Batman writers of all time.

The Winter Soldier

Sometimes, an idea comes along that's done so well that you almost don't remember that before it happened, it would've been completely insane to actually do it. "The Winter Soldier" is one of those—looking back on it now, it's one of the most foundational modern stories at Marvel, restructuring Captain America's supporting cast and providing the source material for some of the best-loved superhero movies ever filmed. In 2005, though, when Ed Brubaker, Steve Epting, and Michael Lark were using it to launch a new Captain America series? It was almost unthinkable. Which is actually one of the things that made it great.

For decades, the joke about death and resurrection in the Marvel Universe was that the only people who actually stayed dead were Uncle Ben, Gwen Stacy, and Bucky, who'd been revealed to have been killed in action by Baron Zemo when Captain America made his return in Avengers #4 back in 1964. With the Winter Soldier, Brubaker and Epting took one of those inviolable rules and threw it right out the window, and they did it in a way where every piece of it sounds worse than the last.

Imagine going back to 2004 and telling someone that not only was Bucky coming back to life, but he was coming back as a brainwashed Soviet assassin with a cybernetic arm who used the training he got as a teenage assassin to try to kill Captain America and then became the new Captain America after Steve Rogers was gunned down on the way to his own trial for treason. That sounds like the worst possible Captain America story, but it's absolutely one of the best Cap stories of all time, and restored Bucky Barnes to being one of Marvel's most compelling characters.

Gwenpool isn't who you think she is

I wouldn't really say that Gwenpool, the current Marvel title from Chris Hastings and Gurihiru is a "bad idea," but it is one that's hard to explain, and that's almost as bad. With most comics, you want the high concept to have an easy to hook to lure people in, something snappy that you can fit into a title—an idea that Hastings himself is pretty familiar with as the creator of The Adventures of Dr. McNinja, a long-running and extremely good comic about a doctor who is also a ninja.

With Gwenpool, it's complicated by the fact that the title character is absolutely not what she seems to be at first glance. She has her roots in a series of variant covers where Spider-Man's late, lamented girlfriend Gwen Stacy was mashed up with various characters, which in this case was, of course, Deadpool. Here's the weird part: despite the name very familiar costume style, the character that's been starring in her own book for the past few years is not a Gwen Stacy/Deadpool mashup, which actually is a pretty awful idea. The concept behind the character is that her name is Gwen Poole, and she's a person from our world, the one where Marvel comics are fictional stories sold in comic shops, who wound up transported into the Marvel Universe.

That's a genuinely amazing concept, and leads to some of the best storytelling that comics have seen recently: Gwen's "power" is that she's fully aware that she's starring in her own comic and is therefore very unlikely to permanently die, and since she has a disregard for bystanders that comes from the fact that she knows they're just insignificant background characters, found herself pretty easily sliding into the role of a supervillain. The way that premise is twisted around into a story that blends metatextual commentary and innovative superhero action is incredible. The only problem is convincing people that the book isn't what they think it is based on the title, and starting any discussion with "no, you're actually wrong about what you think this book is" can often start you off on the wrong foot when you're trying to hook a reader. Take this all with a grain of salt, as it's specifically coming from the office at Marvel where I've been doing most of my comics writing work lately, but it's one of the best comics to come along in a long while.

RoboCop vs. Terminator, the crossover you didn't know you needed

Ever since the Justice Society first gathered around their oversized table back in 1940, comics have played host to countless crossovers, and once they got around to licensing movies and TV shows, the possibilities became endless. It is, after all, a lot easier (and way more cost-effective) to just draw two of your favorite characters hanging out together than to lure in a couple of actors to do the job. Unfortunately, that also means that the market was absolutely overflowing with crossovers in the '90s, and while the creators behind them were usually trying their best and wound up making some pretty fun moments, most of the results were, at best, just okay.

RoboCop vs. Terminator, on the other hand, rules harder than any other crossover, with the possible exception of Archie vs. Predator. That book, though, at least has the wild shock-value of its premise to carry it to readers who have to see how that works. RoboCop and Terminator, on the other hand, are just close enough that they shouldn't work. They're two different kinds of sci-fi, a time-travel action story set against a near-future satire. It's easy to put the two characters against each other, but creating a world where that action makes any kind of sense? That's a lot harder.

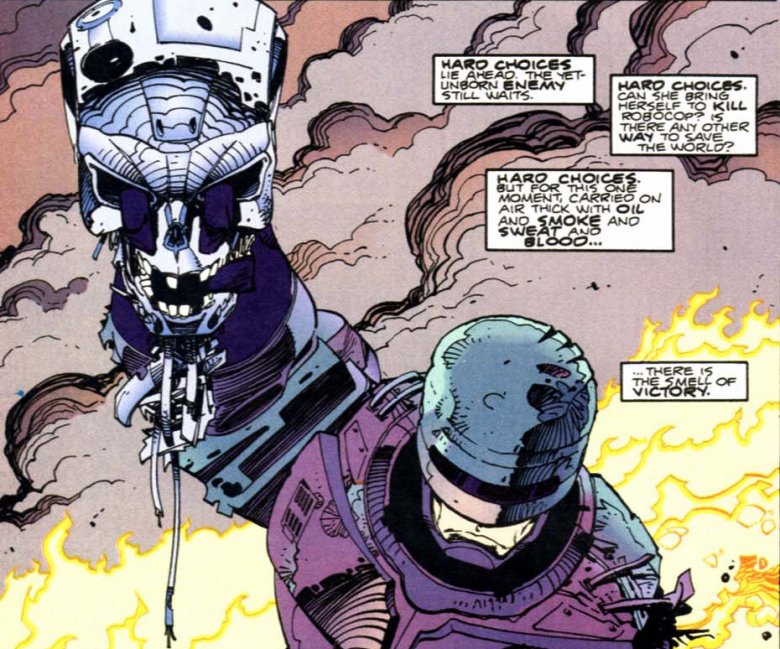

This one pulls it off in a way that makes it seem effortless, mostly because it's from two of the all-time greatest comics creators working at the top of their game: Frank Miller and Walt Simonson. Released in 1992, it might actually be the last truly great Frank Miller comic, and while Simonson is still great, he's hitting the same kind of virtuosic art that made his run on Thor the most definitive take on the character, and one of the greatest runs of all time.

Not only do they manage to create a premise that blends the two series—Alex Murphy's digitized brain and the work done to give him his part man, part machine, all-cop body provides the spark of sentience that allows Skynet to awaken and take over the world and start terminating humanity—it also goes far enough over the top to give you everything you want to see. We see the price of humanity's failure, in that Terminators take to the stars in massive Warhammer 40,000-lookin' spaceships capped off with gigantic silver skulls, and we see that future averted in the most fist-pumpingly awesome way possible. Seriously, this is a book that climaxes with an army of RoboCops, created when Murphy hides his consciousness in Skynet's programming and then takes over a Terminator factory once he wakes up to make soldiers in his own image, taking on an army of Terminators in the battlefields of the future. It's rad as hell, with the expert storytelling to back up its own premise.

It should not possibly be this good, but it absolutely is.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."