The Ending Of Whiplash Explained

What is it worth to be good at something? How hard would you push yourself, how much humiliation would you endure, how much would you pull away from your friends and loved ones, in order to be the absolute best?

Damien Chazelle's "Whiplash," a 2014 best picture nominee, takes these questions to new heights while telling the story of young jazz drummer Andrew Neiman (Miles Teller) and his psychotic mentor Terence Fletcher (J.K. Simmons). Brimming with music a love for musical craftsmanship that Chazelle would expand on in "La La Land," "Whiplash" is nonetheless more analogous to "Rocky" or similar sports movies in the way it focuses on the intense, painful process of pushing oneself well past physical and psychological limits (all of which required Teller to undergo intense training).

A focused, almost businesslike film, "Whiplash" doesn't necessarily endorse Fletcher's horrendous teaching methods, remaining neutral even as the characters end up debating the themes of the movie out loud. Is it worth it to discover the next Charlie Parker if you push your student too far? It's tempting to think that it is, especially with the impression that "Whiplash" leaves with its thrilling, show-stopping finale. But the full impact of the film is more nuanced and thoughtful than a first reading implies. This is the ending of "Whiplash," explained.

We've got Buddy Rich here

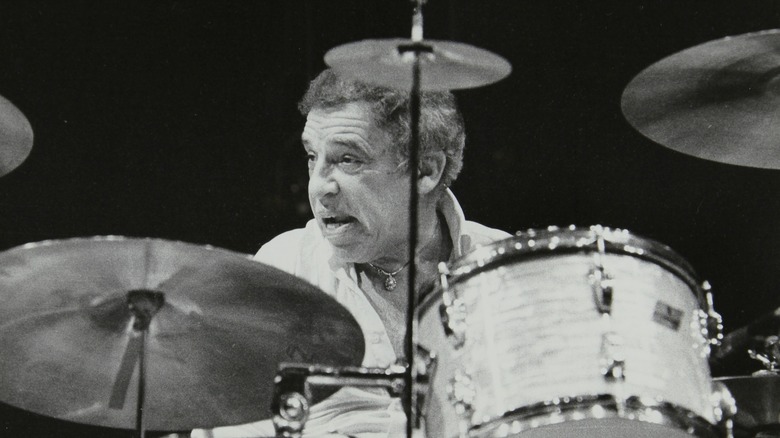

From the beginning, "Whiplash" establishes young Andrew as single-minded and very specific in the type of greatness he is pursuing. Many teenage drummers want to be in rock bands, but he's focused on the complex, fine-tuned art of jazz drumming instead, and even falls asleep looking up at a picture of the legendary Buddy Rich. When Andrew improvises a complicated fill, Fletcher sarcastically says "We've got Buddy Rich here!" While it's easy to assume Andrew idolizes the deceased drummer/bandleader for his pure talent, there might be more to the comparison.

Rich (1917 – 1987) was a mercurial talent and notoriously toxic personality, a genius who was difficult to work with, who often loudly berated the rest of his band when they weren't up to his standards. Tapes of Rich yelling at his touring band were secretly made by pianist Lee Musiker, and became an inextricable part of the jazz legend. There's a reason why most modern audiences know the name from the Beastie Boys' "Sabotage," where the band warns: "I'm Buddy Rich when I fly off the handle."

If this is Andrew's idol, it's no wonder he's set up so perfectly to endure Fletcher's abuse, even to expect it to be the norm in the profession. As Andrew tells his father Jim (Paul Reiser), "I don't want perspective" — he's only at Shaffer to doggedly pursue greatness.

The key is just to relax

The tension of "Whiplash" centers on the true nature of the drillmaster-like Fletcher, perfectly encapsulated in an Oscar-winning performance by J.K. Simmons.

In the rehearsal room, Fletcher is a terse and menacing presence, literally slapping Andrew in the face at points and throwing a chair that barely misses his head. But "off stage," in candid moments, he's completely calm and even congenial. The first time Andrew is about to play with his studio band, he tells him "the key is just to relax," and to "be yourself."

Mere minutes after these instructions, he drives Andrew to tears with relentless verbal abuse. Which is the true Fletcher? He takes the news of one of his former student's deaths particularly hard later in the movie, before it's revealed that student took his own life and Fletcher's aggressive methods may have played a role.

"Whiplash" doesn't give the viewer much information about Fletcher's home life, or his background beyond a commitment to musical excellence, so his character remains an enigma in many ways at the end of the film. Does he do all of this because he cares, or does he take a sick pleasure in putting his charges through the disorienting whiplash (no pun intended) of smiling at them when they're not being yelled at?

Did Fletcher take the folder?

Initially a mere understudy in Fletcher's prestigious Shaffer Studio Band, Andrew gets a big "break" when he seemingly misplaces a folder.

Primary drummer Carl Tanner (Nate Lang) puts Andrew in charge of holding his sheet music, but when Andrew puts it down for a second to use a vending machine, it mysteriously disappears. Since Carl doesn't have the band's entire routine memorized but Andrew does, he takes over the role of "core drummer" for the performance that night and moving forward.

Reading between the lines, it seems like Fletcher is most likely the person who stole the folder, even if he does put on a good act of outrage as he becomes aware of its disappearance. Without context on its significance, it seems very unlikely that a stranger or janitor would pick it up in the brief moment Andrew leaves it unattended.

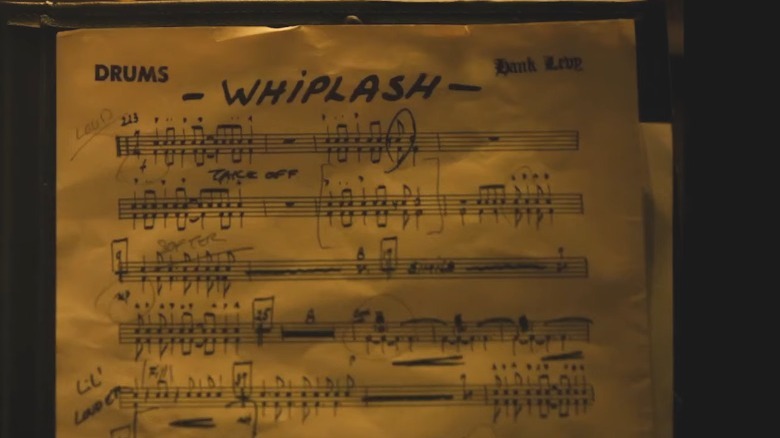

Based on the driving motivation to prove himself by his hard work and talent, Andrew didn't pretend to lose it, either. Late in the film, when Andrew rejoins Fletcher after his firing for the JVC performance, he's using sheet music for "Whiplash" that have the exact same "loud" and "softer" hand-written notes that were seen on Carl's sheets earlier. While it's not explicitly confirmed, Fletcher might have given Andrew the very same missing sheet music.

It's only Division III

"Whiplash" is such a single-minded story that it can a little hard to parse the deeper meanings of the few scenes when nobody's playing an instrument. Near the middle of the film, as Andrew is getting deeper and deeper under Fletcher's spell, he has an uncomfortable dinner with his father and some extended family. His uncle and aunt brag endlessly about his cousin's athletic achievements in college football, displaying virtually no understanding or respect for Andrew's burgeoning career as a musician.

It drives home a theme about the relative thanklessness of certain kinds of art; even though his cousin only plays in Division III college football, it's more universally understood and admirable to the average citizen than Andrew's rapid ascent to being the drummer for a music conservatory's jazz band. What's unclear, especially without any other scenes of Andrew interacting with these people, it why he gets so irritated about it. Does he feel misunderstood, or is his time with Fletcher turning his formerly polite teenage enthusiasm into a curdled cynicism? Did Andrew retreat so thoroughly into drumming because he has nothing in common with these people, or is drumming what's driving them all apart?

The most precise jazz ever

Although the performance sequences are intense and captivating, "Whiplash" doesn't really feel like a film with music in its bones. It focuses so thoroughly on precision, on dedication, and on the literal blood, sweat, and tears that Andrew leaves on his drum set that by the end of the movie the viewer could be forgiven for forgetting that music has any lightness to it at all. It's not clear why Andrew became a musician instead of pursuing some other discipline; outside of conservatories and school competitions, the performing arts are more about loving what you do than striving to be the objective best in a subjective art form.

Writing about the film for The New Yorker in 2014, Richard Brody pointed out that "Andrew isn't in a band or a combo, doesn't get together with his fellow-students and jam," nor is he ever shown to study music theory, or even talk about music with any of his peers. Why does he love jazz? What drew him to the drums? As compelling a story about greatness and mentorship as "Whiplash" is, it presents a strange, bizarre version of jazz that has no improvisation and seemingly no love for the fluidity, organic nature of performance. Instead, it's all precision and self-control.

Shaffer's severe consequences

The disciplinary policies of the Shaffer Conservatory of Music are apparently quite severe. After attacking Fletcher on stage when he's dismissed in the middle of a performance, Andrew is summarily expelled from Shaffer, which seems pretty harsh. You have to wonder if Shaffer, in investigating an incident involving a teacher who employs brutish methods, even asked for Andrew's side of the story. Facing a possible dismissal from a position he lived in constant fear of losing, Andrew got up and walked away from a serious car accident to attempt to perform while badly hurt.

Fletcher, Shaffer's employee and alleged "adult" in the room, allowed a 19-year-old kid to play the drums while covered in blood. When it goes badly, and the delirious student's response to being reprimanded for failure is to take a swing at his professor, their only response was to expel the student and ask no other questions? Months later, they apparently take Andrew's anonymous testimony about Fletcher's methods serious enough to fire the teacher, but where was that due diligence previously?

Charlie Parker and the cymbal

Twice over the course of "Whiplash," Fletcher invokes a legendary anecdote about jazz great Charlie Parker as a way to justify the way he operates. Allegedly, drummer and band leader Jo Jones once threw a cymbal at a young Charlie Parker's head for playing badly, "nearly decapitated" him Fletcher says, and this inspired Parker to go home and practice obsessively. Never mind Parker's entire life story, his years of hard work and practice before that, this one humiliating and terrifying incident supposedly drove Parker to become one of the greats.

According to The Guardian's jazz critic John Fordham, the real incident isn't so easily reduced to a parable about the usefulness of cruelty. A teenage Parker had been perfecting his own method of improvising in entirely new and unexpected keys, which initially impressed Jones until the self-taught high school dropout lost the tune on the next chord. "Jones contemptuously threw a cymbal at his feet," not his head, and Parker vowed to return and finally prove his innovative, already revolutionary talent. He was great at the time, his resolve strengthened by the mildly embarrassing toss of a cymbal; fearing for his life wasn't really a factor.

No time for love

The most unique, unexpected part of "Whiplash" might be the handling of Andrew's brief relationship with Nicole (Melissa Benoist). Too often in stories about a male protagonist, the love interest is only there to validate him for his dedication, to be a kind of trophy that he "earns" by single-mindedly pursuing some sort of goal. But "Whiplash" makes it clear that love and the obsessive pursuit of artistic excellence aren't necessarily compatible. Andrew seems to be self-aware enough to realize this, although he's extraordinarily cold in the way he breaks up with Nicole.

After a brief break from drumming, he doesn't seem to regret the way he was unable to find balance in life, calling Nicole to awkwardly apologize and invite her to the JVC performance. But refreshingly, Nicole has a new boyfriend, and doesn't show up. Love is something that requires actual space and balance in your life to maintain, and "Whiplash" strikes a small but important note of originality in having Nicole ignore Andrew's feeble attempt at reconciliation.

Fletcher's revenge

In a thoroughly predictable twist, when Fletcher invites Andrew to be part of his new band's JVC performance, it is with an ulterior motive.

Fletcher is entirely aware that it was Andrew's "anonymous" testimony that got him fired from Shaffer, and specifically invited Andrew to his new band in order to have the rest of the band play a song Andrew hasn't rehearsed and doesn't have the sheet music for, humiliating him once again. In this moment, the viewer learns that Fletcher is not only devious and holds grudges, he's also impossibly petty.

You'd think he would be trying to rehabilitate his image after being summarily fired from Shaffer; purposefully embarrassing one of your former students (one of the very ones you were fired for bullying) doesn't seem like the way to do so. Or even from the objective point of view of the crowd at the show, it doesn't reflect well on the conductor for the drummer to be entirely off-beat and befuddled. Fletcher has apparently decided to make his career tailspin even worse, just to get one over on a 20-year-old kid.

The endless drum solo

After being batted around like a pinball the entire movie, more or less, Andrew snaps after Fletcher's bait-and-switch at the JVC show and storms back on stage. Hijacking the role of bandleader, he begins to play "Caravan" while Fletcher is talking, cuing the rest of the band when to start himself. Despite Fletcher staring daggers at him, Andrew carries the band through a flawless performance of the song he spent months practicing at Shaffer.

But this act of rebellion in itself isn't enough; when the rest of the band stops, Andrew continues with a rolling, virtuosic drum solo that serves many purposes. It continues to stick it to Fletcher, but it also releases the pent up tension of Andrew wanting to impress this man who turned out to be a petty bully. In the moment, he finally seems to be enjoying playing the drums instead of being petrified about what it means for his future or to some authority figure. The sheer explosiveness and catharsis of the solo even infects Fletcher, who gets over himself and joins Andrew in bringing it to a stillness before ramping it back up into the finale.

Eye contact

The psychological flow of music is a powerful thing. It slows down time and creates an engrossing present that is immune to personal grudges and circumstance.

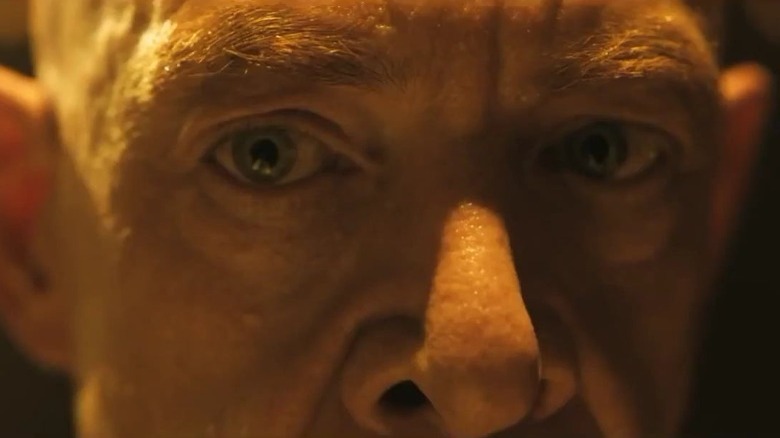

Mere minutes after Fletcher's revenge prank, followed by Andrew's storming the stage and hijacking the JVC performance entirely, the bitter rivals connect during the drum solo and finally are on the same tempo, so to speak. In a brilliant reverse shot, Chazelle focuses all the way in on Andrew's face as he innocently looks up, covered in sweat, to see if he's finally earned the respect of his old teacher.

In that instant, viewers can see Fletcher's brows finally un-knit, as his face relaxes into a smile we're only shown in its corners. After becoming a monster and losing his job, he sees in this moment that he may have finally found his Charlie Parker in the talent and newfound audacious nerve that Andrew has suddenly displayed. After an entire runtime of tension, "Whiplash" ends with a moment of eye contact — and a joyous feeling of relief.

Do the ends justify the means?

Many films about villainry and the inhumane treatment of others deals with an important question: Does depicting cruelty endorse it?

It's easy to get caught up in the show-stopping final scene of "Whiplash" and think that the movie is implying all of Fletcher's methods have been worth it to create this one moment, where Andrew shines with undeniable talent. Fletcher has found his Charlie Parker, and has seemingly been proven right in his philosophy that "good job" is the most poisonous thing a young musician can hear.

But this conclusion requires willfully forgetting the rest of the movie, which is rather straightforward about whether Fletcher's attitude is correct; one student kills himself, and Andrew nearly gets himself killed just trying to make it to a show on time to avoid Fletcher's wrath. By the end of the movie, Andrew has blown off his relationship with Nicole, alienated his extended family, and even his endlessly-supportive father is watching Andrew's performance with a mixture of awe and terror.

While the end results are undeniably impressive, you can see genuine fear for what his son is putting himself through. Talent, perhaps, isn't worth sacrificing your humanity.