That's What's Up: Why Superheroes Don't Have Sidekicks Anymore

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: Almost every major superhero had a kid sidekick of some sort once, but now they hardly exist anymore except for Batman, who already has a small army of them and still gets a new one every few years. Why does he get away with child endangerment while other superheroes don't? — J. Chow, via email

When you get right down to it, kid sidekicks are a lot like capes. They're an element that's so inextricably tied to the very idea of the superhero that they serve as a sort of shorthand for the entire genre. It's one of the reasons that you see them cropping up so often when non-superhero media, like sitcoms, inevitably turn their attention to comics. There's always a Fallout Boy to stand next to Radioactive Man, cape billowing in the wind, even though modern comics pretty much moved past capes and kids about 50 years ago.

As for why they're still so prominent in the pop culture idea of comics, though, that one comes down to a single word: Robin. And come to think of it, you can answer the question of why we don't have them anymore in the same way. In 1961, there was a massive shift in the idea of what a superhero could be that comes down to one single word. Although to be fair, that one does have a hyphen.

Sidekick history

It probably goes without saying, but comics didn't invent the idea of a hero with a sidekick. Like a lot of elements of those early superhero stories, it was something that descended pretty directly from pulp characters like the Lone Ranger and Tonto, which in turn are mainly there for the sake of narrative convenience. As radio shows in particular grew to dominate pop culture, it was very handy to have someone that the main character could talk to, and that idea was built into the genre from that point on. It's the reason why Jimmy Olsen, for instance, was created for the Adventures of Superman radio show, and only made his way into the comics after being a hit there.

Even before that, though, heroic literature was full of 'em. Don Quixote had Sancho Panza, the Scarlet Pimpernel had Marguerite Blakeney, and Robin Hood—basically the foundation on which the modern adventure hero is built—has an entire roster of them from Little John and Friar Tuck all the way down to lesser known associates like Much the Miller's Son. Even the specific idea of a kid sidekick is part of the tradition. Robin Hood had Will Scarlet pitching in with the rest of the Merry Men, Beowulf had Wiglaf to help him out against the dragon, and Hercules had Iolaus, a sidekick and lover that would've driven Frederic Wertham insane, searing the Hydra's neck-stumps every time he chopped off one of its heads.

When superheroes arrived on the scene, though, the sidekick became more than just a sounding board for ideas, a plot point in need of rescue, or an extra set of hands, even though they were all of those things. They became a crucial part of what made the genre appealing.

The two-man team that redefined the two-man team

In the Golden Age, with Superman's arrival kicking off the genre and his massive success prompting a wave of imitators, comics were finding an audience among all ages. That makes sense, too—in an era before television, they were a form of visual entertainment that was cheaper and more permanent than going to the movies. Sure, superheroes dominated, but there were a wide variety of stories to choose from, and the lurid pre-code crime and horror comics were able to get a foothold in older audiences.

That said, superheroes (and Superman in particular) had been a hit with kids since day one, thanks to the bright colors, fantastical adventures, and easy to follow hero-vs.-villain storytelling. Since that's where the money was, plenty of other characters tried to get in on that action by making themselves more appealing to the kids. And, perhaps unsurprisingly, the most successful new direction came from the character who had already been the most successful new hero of that post-Superman gold rush: Batman.

The original version of the character had been a pretty shameless riff on the Shadow, to the point where Bruce Wayne's debut story in Detective Comics #27 had been, to put it charitably, "inspired" by a similar adventure for the mind-clouding, gun-toting pulp vigilante. When Batman finally got his origin story six months later, though—arguably the single most important thing about the character—it was built around a fear that kids could very easily relate to. Creators like Bill Finger and Jerry Robinson were already pushing Batman closer to a character that would appeal more to kids, and in Detective #38, they cemented it by introducing a character specifically designed to do just that.

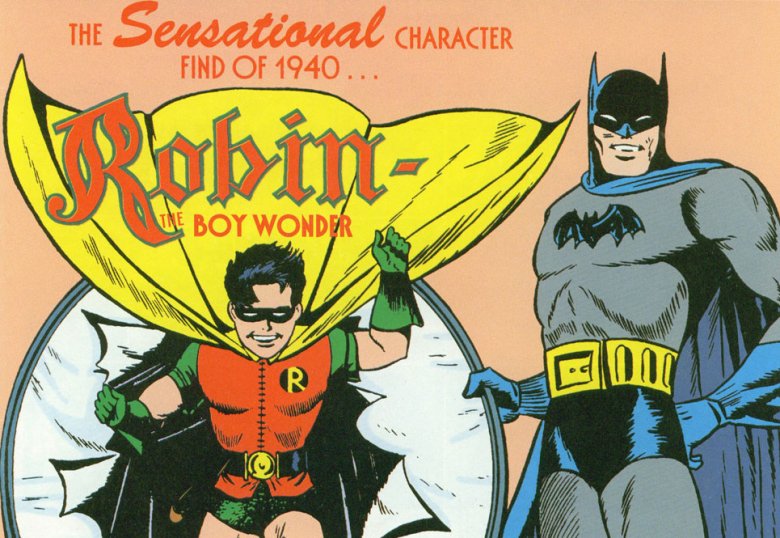

Only 11 issues after introducing Batman himself, the same month that they'd spin him off from the lead character of an anthology and into a solo title, Finger, Robinson, and Bob Kane introduced the Sensational Character Find of 1940: Robin, the Boy Wonder.

Hey kids! Comics!

In the absolutely essential The Caped Crusade: Batman and the Rise of Nerd Culture, author Glen Weldon cites Robin's arrival as the final element in making Batman the character that we recognize today, and refers to Batman and Robin as the two-man team that redefined the very idea of what a two-man team was. He's not wrong, either.

It worked beautifully, and to say that Robin was a hit is underselling it by quite a bit. The secret of that success was simple: as much as kids could look up to characters like Superman, it was a lot easier to see themselves reflected in a kid their age. Fifty years later, that's absolutely how it worked for me when I was a kid watching the Batman TV show. I never imagined myself as Batman, but Robin? Batman's biggest fan, who got to hang out and fight crime alongside his hero? That's who I always pretended to be, riding around the neighborhood with a yellow bath towel tied around my neck and a pair of green dishwashing gloves. I've got a pretty good guess that my experience wasn't unique, either.

If you really need an indication of how successful Robin was as a character, consider this: not only did he stick around as a major part of the Batman mythos for the next eight decades, he also wound up being such a hit that he even appeared in solo stories without Batman. In 1947, he became the lead feature in Star Spangled Comics, and stayed there for the next five years until the series was rebooted as Star Spangled War Stories. And, like Batman and Superman before him, he kicked off a massive wave of imitators.

Bucky, Freddy, Stuff, and others

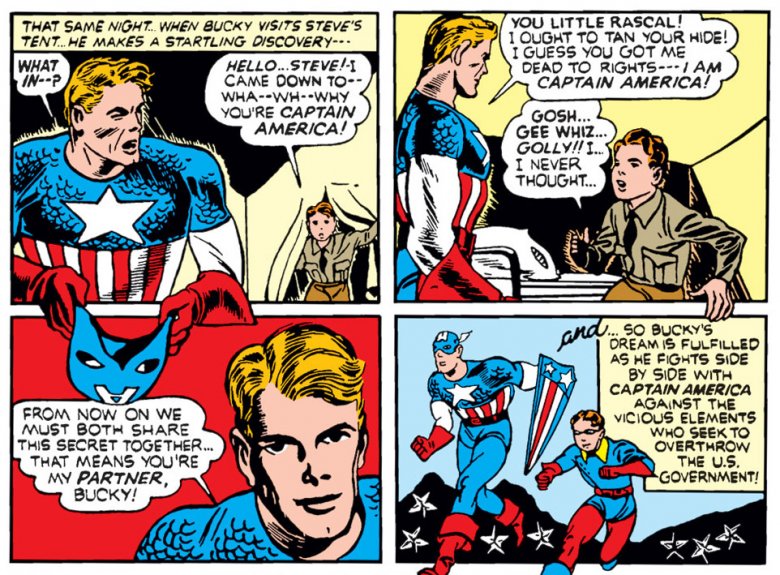

After Robin, having a kid sidekick was about as necessary as a costume for a new superhero. In his first appearance in 1941, Captain America was teamed up with Bucky Barnes, who would wind up being one of the most important characters in Marvel's roster in the 21st century when he unexpectedly came back from the dead. The Sandman got a less pulp-inspired costume and a sidekick named Sandy the Golden Boy that same year. In 1942, Green Arrow acquired an orphan of his own named Speedy, and the Guardian started hanging out with an entire gang of kid sidekicks called the Newsboy Legion, all in the name of giving kids a viewpoint character that would help sell them on the hero.

They served another important function, too, in that they added some much needed diversity to a genre whose stars were overwhelmingly white. Admittedly, most of these characters were ill-considered, poorly presented, and rooted in stereotypes, like the Spirit's young sidekick Ebony (1940) or the Crimson Avenger's chauffeur turned sidekick, Wing, who predated Robin (and Batman, for that matter), but only became a superhero sidekick in 1941. There were, however, very fortunate exceptions to that rule, most notably Stuff, the Chinatown Kid. Appearing alongside the Vigilante in 1942, he's remarkable for not being rooted in a racist caricature, which puts the "everything was like that back then" defense of some of the other, more unfortunate characters on some pretty shaky ground.

There were even a few characters who attempted to flip the script. The Star Spangled Kid, who had originally been the lead feature in Star Spangled Comics until Robin came along to knock him out, was a kid hero with an adult sidekick named Stripesy. An interesting idea, but nowhere near as well-received as another character who did something even more interesting with the idea of giving readers a superheroic kid to relate to.

Shazam!

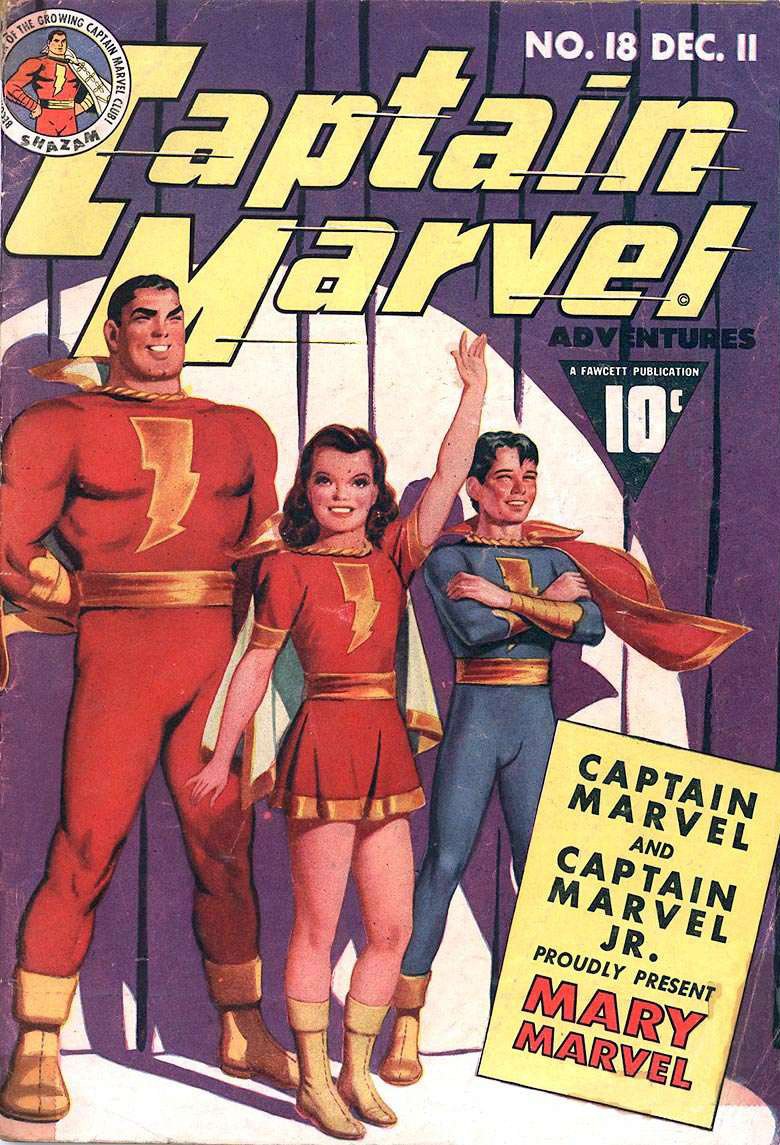

Captain Marvel, better known these days as Shazam, might be the best idea of the entire Golden Age. He's literally just a more fun version of Superman, replacing the alien origin story with a magic spell that makes Billy Batson the kid and the hero at the same time. The power fantasy of a being able to say a magic word and turn into an all-powerful adult is every bit as easy for a young reader to relate to as the fear of losing their parents that connects them to Batman, and the stories that he starred in are years ahead of their time—largely because Otto Binder, the primary writer of Captain Marvel Adventures, would go on to be the most definitive Superman writer of the century.

But while you'd think that Captain Marvel would've just cut out the middleman of having a sidekick entirely, that's not actually how it worked out. Even though he was a kid himself, Billy's relation to Captain Marvel wasn't quite the easy sell that you'd think. He and Captain Marvel were often written as two separate characters who'd do things like surprising each other with Christmas presents, and a year after his creation, he'd wind up having sidekicks of his own. In fact, he'd wind up having more than anyone else.

The big ones were his sister, Mary Marvel, and Captain Marvel Jr., who, despite the name, was actually their friend Freddy Freeman. But there were also the Lieutenant Marvels, three other guys named Billy Batson who found out that they could transform if they said the magic word too; Uncle Dudley, who had no powers and ran around in a homemade costume; and Tawky Tawny, a tiger in a plaid suit who would serve as the template for Jimmy Olsen's later adventures.

Even a character who had that built-in appeal to kids still had to have a sidekick. After Robin was introduced, that was just the way it was. Until 1962, when one hyphenated word arrived and changed everything forever.

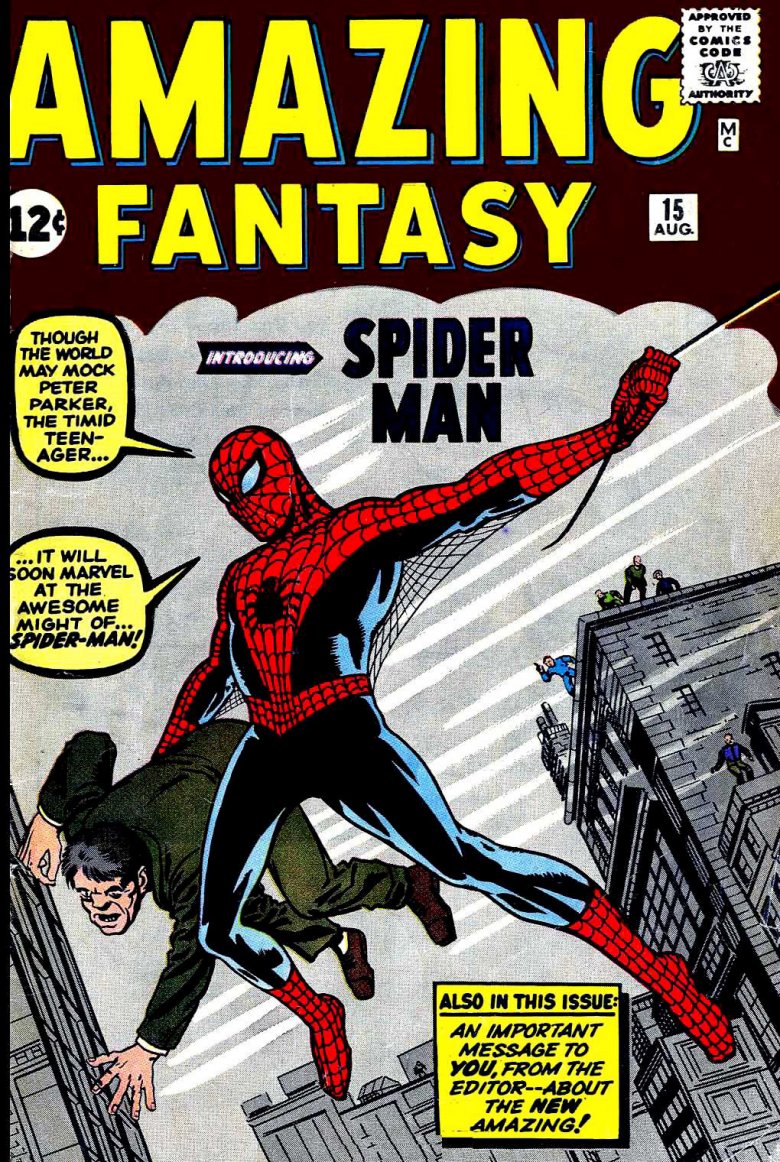

Spider-Man

The first issue of Amazing Spider-Man promises on page one—in a caption box where, incidentally, they forget the hyphen—that readers had never read a story like this, because they'd never seen a hero like Spider-Man. Since I haven't read every comic printed between 1938 and 1962, I'm not entirely sure how accurate that was. I can, however, say with some certainty that if they weren't absolutely correct, Stan Lee, Steve Ditko, and Johnny Dee were close enough that it didn't matter.

Spider-Man's arrival changed everything. All the innovative new techniques that the Marvel bullpen had thrown out in Fantastic Four, blending superheroes with the sci-fi bombast of their '50s monster comics, were refined into something that would be imitated, refined, and repeated almost as often as Superman and Batman. In fact, the only reason it hasn't happened more often is that those two characters had a 20-year head start, and even then, it's pretty close.

There are plenty of specific elements that would crop up again and again. The way Peter Parker's personal life would suffer as a direct result of Spider-Man trying to do the right thing. The emphasis on an interesting supporting cast that would set the stage for a soap operatic approach to drama. The guilt of not using one's power responsibly, rooting characters in their flaws rather than their powers. Those were all things that you can find incorporated into countless new characters, and even mixed into existing ones, after Spider-Man became one of the most popular characters of all time.

But for our purposes today, there's only one thing that really matters: Spider-Man was a teenager.

How do you do, fellow teens?

There had been teenage superheroes before, of course. We've already talked about the Star-Spangled Kid, and just a few years before Spidey hit the page, DC introduced the Legion of Super-Heroes as a whole team of super-powered youngsters from the far-off 30th Century. There was even a teenaged version of Clark Kent called Superboy who was almost as popular as the original. Spider-Man, however, was kind of the first teenage superhero in an era where "teenager" meant something more than just a person whose age was between 12 and 20. It's not a coincidence that he came around in the early '60s, the same time that pop music, TV, and movies were starting to treat teenagers as a distinct socio-economic force.

And the tipoff is right there in the name. Peter Parker's a high schooler, but when he gets his powers, he doesn't call himself Spider-Lad or Spider-Boy, in the way that the young characters of previous generations would. He calls himself Spider-Man.

There's an aspirational nature to that, one that's familiar to a lot of the people we call "young adults" these days. It's arguably the defining trait of the entire demographic, that they're existing in this endlessly frustrating transitional stage between carefree kids and grumpy adults, where every experience is the most it ever is, because they're figuring out who they are. And Peter Parker, when he puts on that mask, isn't a high schooler—he's the adult that he wants to be, and eventually grows into. And the thing is, kids look up to teenagers just as much as they look up to adults.

And that's how Spider-Man killed the very concept of the kid sidekick.

Burdens and aspirations

If the entire point of adding in a kid sidekick was to give younger readers a figure that would be easier for them to identify with, then Spider-Man made that completely unnecessary. He was the relatable kid and the aspirational superhero at the same time. Younger readers could look up to his heroics, teenagers could sympathize with his day-to-day angst, and older readers who remembered their own teenage struggles could get the best of both worlds. If you could make characters who did all that all by themselves, then why bother making another one? Being able to put themselves into the shoes of the hero, the main character, made younger readers feel way more important than being able to identify with the sidekick, and even the narrative conveniences of having someone to explain things to were less necessary thanks to changing the way that storytelling was evolving. If you've got internal monologues and narrative captions, then the reader gets all the information they need.

It doesn't hurt that all this happens around the same time that Robin, the definitive sidekick, was being pretty regularly tied up and rescued in a hugely successful TV show based around a studiously faithful but delightfully campy approach to its source material. Along the same lines, it's not surprising that once Spider-Man was a hit, you had a resurgence of Robin solo stories, along with teams like the Teen Titans and the X-Men, who were originally billed as the Strangest Teens of All.

But that brings us back around to the question of why it kept on working for Batman. Part of it, of course, is that Robin has the legacy of being the first great sidekick in comics, and all the historical importance that goes with it, but there's something else to it, something that made the Batman family expand even more in the modern age than it ever had before.

It's because the existence of characters like Robin, Batgirl, Nightwing, Orphan, Spoiler, Batwoman and even Alfred create a cast that resonates perfectly with that origin story. The defining moment of Batman's origin story is the loss of his family, and in showing us that he can create a new one, we can actually see the victory that makes him work as a character. For all the silliness of a guy throwing batarangs and fighting the Riddler, Bruce Wayne is there to help Dick Grayson when his parents are murdered in front of him, in the way that no one was there to help him. That's what makes it work. But it's also a pretty hard legacy for anyone else to live up to.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."