Small Details You May Have Missed In Akira

In 1989, a year after its initial release, "Akira" premiered in the U.S. and changed the country's perception of animation's possibilities forever (via Box Office Mojo). It wasn't the first anime to cross the pond, but most of its predecessors had been cheap, kid-friendly fare like "Astro Boy" and "Speed Racer" — in other words, the most American Japanese cartoons.

"Akira" was something else altogether: a dark, violent story that touched on difficult themes, all within a lushly realized, believable future world. Adapting his own then-ongoing comic series, writer/director Katsuhiro Otomo tells the story of a dystopian Neo-Tokyo. The old city had been destroyed in the psychic blast released by the title character 30 years earlier, and even after rebuilding, Neo-Tokyo's still constantly on the verge of collapse. It gets the final nudge it needs when teenage biker Tetsuo gains Akira-level powers, and his former buddy Kaneda has to join the combined government and anti-government factions trying to take him down.

Even if you've never seen it, you probably know its images — Tetsuo's horrifying transformation when he finally loses control, the candy-colored neon nightmare that defined the cyberpunk genre, and Kaneda's sideways bike slide that's been copied endlessly, most recently in "Nope." But beyond these big, flashy moments, there are smaller ones that may take an extra viewing or two to catch. Here are just a few.

Just how many details there are

"Akira" premiered at the tail end of the "dark age" of American animation. As detailed in Leonard Maltin's "Of Mice and Magic," the shorts market that had fueled the industry for so many years had vanished, replaced by shoestring TV series whose main innovation was finding new ways to put as little animation in their animation as possible. This style of "limited animation" became standard operating procedure, even at the once-mighty Disney, left rudderless after its founder's death.

By the time "Akira" reached U.S. shores, the homegrown animation industry was beginning to recover, but Otomo's film still must have been a revelation. The team at Tokyo Movie Shinsha cut as few corners as possible, and their craft is still jaw-dropping, even compared to other big-budget animation. For one thing, the early success of "stars" like Felix the Cat and Mickey Mouse ensured American animation was all about character, lumping everything else — smoke, water, fire — under "effects animation." But those are things that interested TMS the most.

From the beginning, they focused on details almost any other studio would ignore, like the reflections in a glass of beer or on a CD in the jukebox. And while nearly all hand-drawn animation uses static backgrounds, "Akira" features multiple live-action-style "tracking shots" that required the animators to redraw the settings 24 times a second (via The Japan Times). Even the subtle colors of a background extra's cigarette lighter show more care than the main characters of most animated movies. And, it's all building up to the horrifying climax, where Otomo shows us far more than we'd want to see.

Akira adapts comics speed lines to animation

One of the biggest challenges in creating comics is making still images seem to move. Fortunately, the medium came into maturity along with another one that faced the same problem — photography. The pioneers of comics looked there for inspiration, simulating motion blurs with rows of lines arching in the character's path of movement, sometimes accompanied by puffs of smoke when they needed to indicate someone going really fast.

As a comic artist, Katsuhiro Otomo would have been familiar with this technique, and he uses it throughout the "Akira" manga. And while animation doesn't have to deal with the limitations of still images on paper, Otomo finds a way to make the shorthand of his original medium work in his adaptation.

He does this most strikingly in the first bike chase, where the road turns into a river of shooting lines under the motorcycles' wheels. And if this seems unnecessary since we can see how fast the bikes moving, the use of comics shorthand takes the chase into a hyperreal realm, creating a sense of dynamism that's impossible in live action. Otomo tracks the bikers' movements in other ways, too — the billowing smoke they kick up behind them, the flying garbage as one poor sucker plows through a trash pile, and the streamers of light their taillights leave behind, possibly inspired by "Tron" a few years earlier.

The Clown gang is a multilingual pun

Before the protagonists are drawn into a much bigger world of godlike powers and political intrigue, the main conflict seems to be between two biker gangs, the Capsules and the Clowns. Colorful gangs are nothing new, but the Clowns are one of the few times this brutally realistic film reflects its comic-book origins — their leader's even named "Joker."

But there's more to their warpaint than just looking cool. Like many other countries, Japan developed a postwar biker culture, but it differed enough from its Western equivalents that the Japanese word "bōsōzoku" (translated by Metropolis as "joyride tribe") is almost always left untranslated. For one thing, instead of leather, they preferred to wear mishmashes of Imperial Japanese and American military uniforms, and they saw the whole lifestyle as one big show, with the street as their stage.

Speaking of performance, many viewers are likely to have a very different association with "bōsō." Ever since Pinto Colvig, the voice behind Disney's Goofy, began performing as Bozo the Clown, first on record and then on TV, the name has been synonymous with clowns, both literal and metaphorical. Knowing all that, it's hard not to see some sly wordplay going on with the Clowns' choice of gang colors. The Funimation translation all but spells it out in the interrogation scene, where one officer dismisses the Capsules as "bozos."

The attack dog scene takes aim at traditional animation

As we've said, "Akira" was the first animation for adults to take off in America since "Fritz the Cat" over a decade earlier. That was far from a novelty in Japan, though — even Osamu Tezuka, the "god of manga" and creator of "Astro Boy," produced some films so adult they could have gotten an X rating, and "Akira" opened alongside the harrowing war story "Grave of the Fireflies." But even if an adult anime isn't quite as subversive as it seems to American viewers, you can still see Otomo reveling in the movie's blood-soaked transgressiveness.

The most obvious example is when we first meet the psychic child Takashi being dragged through Neo-Tokyo by a badly injured revolutionary. In a moment reminiscent of the previous year's "Robocop," they pass by a TV store that interrupts the news of violent turmoil with a cutesy, cartoony ad for dog food.

That would be the everyday "reality" of most animated films. But, we quickly see how different the world of "Akira" is when the scene cuts to a pack of realistically rendered attack dogs that tear bloody chunks out of their quarry, and gush blood themselves as he shoots back. Like the punk rockers of his youth, Otomo's putting up a big fat middle finger to his predecessors in the medium as he shows just how much more it's capable of.

Tetsuo's first use of his powers parallels a Russian classic

As they recover Takashi, the Neo-Tokyo government picks up Tetsuo for testing as well. The scans reveal how powerfully psychic Tetsuo is, and he confirms it by getting up and walking out of the facility without any of the security forces seeing him. When he's recaptured, we see him beginning to realize the extent of his powers when he moves a glass across his meal tray.

A very similar scene played out almost a decade earlier in the great Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky's science fiction classic, "Stalker." In it, a mysterious "Zone" with its own laws of physics has appeared in Russia. At its center is a Room that grants visitors' wishes, so the titular tracker takes two men only known as Writer and Professor on an expedition to find it.

There are also mentions of the Zone causing mutations, much like the mutant children in "Akira." Stalker's daughter, nicknamed "Monkey," is one of them, but at first, the mutation seems to extend only as far as her malformed legs. Stalker goes to the Zone trying and failing to find transcendence, which Tarkovsky visualizes with a trick borrowed from "The Wizard of Oz" where the normal world is sepia-toned, but the Zone is in color. Savvy viewers should know something's up when they see the film stays in color after Stalker returns home. The last scene confirms the magic he's been looking for has been at home all along, when Monkey, just like Tetsuo, manifests her telekinetic powers by moving glasses across the dinner table.

The Baby Room shows childhood as a prison

The main cast's arc in "Akira" neatly dovetails with the arc of "Akira" itself — angry adolescents struggling to escape childhood's shadow, and prove themselves as independent adults. In Tetsuo's case, that leads to a massive power trip that destroys everything in its path, but the alternative presented by the other psychics doesn't look much better.

Despite the epilogue revealing the Numbers are about the same age as Tetsuo, they spend their lives trapped in between childhood and extreme old age, confined to a "Baby Room." On paper, it sounds like a wonderland, decorated with soothing murals and filled with toys and giant sculptures of everything kids think is cool — elephants, planes, zeppelins. But, the somber blue lighting gives the whole place an ominous atmosphere, and Otomo can't resist a shot at Disney in a relief based on their version of "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs."

That atmosphere turns downright terrifying when the kids show up to defend themselves from Tetsuo, armoring themselves with piles of toys formed into the shape of giant playthings turned monstrous — dead-eyed, sharp-toothed, sharp-clawed, and dripping milk. In other words, they're using the relics of childhood to protect themselves from the adult world, building a prison within their prison.

Kaneda is a literal bigmouth

Kaneda is an unlikely choice for the hero of a sci-fi epic. He's barely even an anti-hero, relentlessly pursuing the vocally uninterested Kei with smarmy, blustery attitude and moves that would make a pick-up artist blush. He's thrown into action he's totally unprepared for and loudly complains about things like sneaking through sewers that a more traditional action hero wouldn't even notice. But in the end, he steps up, willing to kill his best friend and risk his own life to save the world.

As Scout McCloud points out in "Making Comics," one of the biggest differences between American comics and manga, and by extension anime, is the willingness to use exaggeratedly cartoony designs in serious work. While Otomo's style is far more realistic than the average anime creator's, he's still willing to exaggerate his protagonist to efficiently establish his character. As Strong Bad once explained, an anime character's mouth should be "real tiny when it's closed, ridiculously huge when it's open." And since Kaneda rarely stops talking, his mouth is always ridiculously huge, making it easy to understand why the other characters are so exhausted from listening to him.

The rat in the government is designed to look like a rat

For most of the movie, Colonel Shikishima is the only one to take the threat Tetsuo poses seriously. Unfortunately, none of the higher-ups are willing to listen to him, about that, or about his suspicions there's a mole in his research facility.

He's right about both: The diminutive parliamentarian Nezu has joined the resistance and fed them information about the facility's security so they can liberate Tetsuo. While the subtitles refer to Nezu as a "mole," he's designed with another small animal in mind — fitting, since you could just as easily say he ratted his colleagues out. His height, grey hair, and especially his buckteeth make it obvious he's the rat long before we see him aiding the resistance. Even his death is appropriately rodentlike: He has a heart attack trying to escape Shikishima's purge of the cabinet, frantically shovels pills into his mouth, and dies foaming at the mouth like a poisoned rat.

Tetsuo's power subtly changes his appearance before his final transformation

The movie's signature scene comes near the end, where Tetsuo's uncontrollable power wreaks havoc on his body, turning him into a writhing mass of barely human flesh. But if you pay close attention, you can see him starting to change long before that. When he's first introduced, Tetsuo's a pretty normal-looking kid, with a healthy complexion, short hair, and maybe a slightly larger-than-average forehead. When he meets the corpse-grey Numbers in the Baby Room, it starts to become apparent that Tetsuo's started turning paler himself. Once you notice that, other changes become more obvious. His forehead seems to be expanding to hold his newly powerful brain, and then there's his trademark hair. Spiky hairdos are nothing new in anime, but Tetsuo's design serves a narrative purpose here, looking like it's been electrified by the seething power growing in his mind.

Tetsuo announces he's become a superman by putting on a red cape

In some ways, "Akira" is an anti-superhero movie: the story of a being with incredible power but no responsibility, causing destruction instead of preventing it, first to the city and then to himself.

If nothing else, one costume choice suggests that's exactly how Tetsuo sees himself. After he escapes Shishima the second time, he's followed through the streets by a Messianic cult, and he seems to realize jeans and a white tank top won't cut it for his new role. So, he breaks through a store window and rips the red dress off a mannequin to wear as a cape. The connection to royalty is clear, but so is the reference to the original comic-book superhero, Superman. And if it wasn't already, it should be when Tetsuo starts flying with the cape fluttering behind him, hefting a multi-ton deep freeze over his head.

The title got lost between page and screen

Adapting a six-volume comic into a two-hour movie is hardly easy, especially when only four of those volumes are finished. So, Otomo had to be ruthless with his own work, and even the title character wasn't safe. In the movie, he's enough of an offscreen presence to more or less justify its title, since he's responsible for the existence of Neo-Tokyo, and while the military tries to prevent Tetsuo from becoming a new Akira, his followers celebrate him as the psychic boy's reincarnation. But in the end, it turns out Akira is long gone — all that the containment freezer hidden under the Olympic stadium contains are the few scraps of his body remaining after the government cut him up to find out what went wrong.

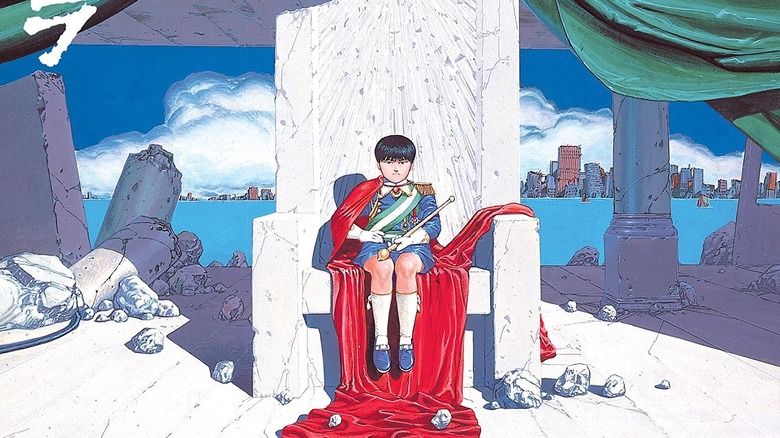

Akira plays a much more active role in the comic series, where he's perfectly preserved in the containment unit, still the same age he was 30 years earlier. He, not Tetsuo, is responsible for the destruction of Neo-Tokyo, which happens partway through the narrative instead of at the end. This gives Otomo space to explore the aftermath, with Akira as Tetsuo's puppet ruler as they take control of the ruins. But, that was too much story for a movie that was already bursting at the seams, so by the time it hit theaters, Akira appeared for a grand total of one shot as the other Numbers — maybe literally, maybe metaphorically — resurrect him from his pickled remains.

Tetsuo's final transformation shows him as he really is

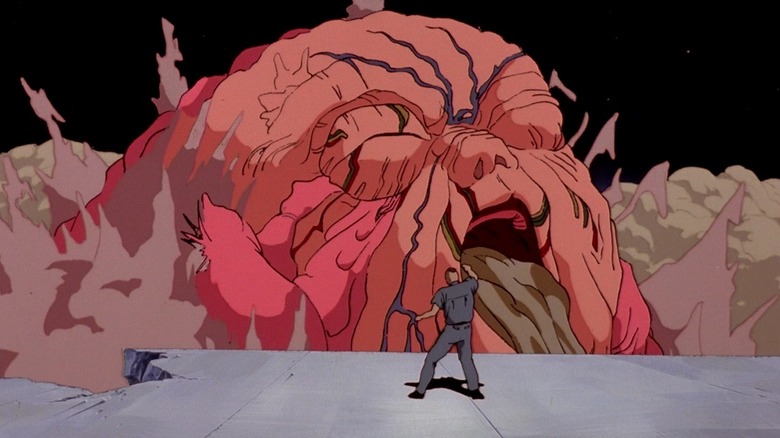

If "Akira" is a story about growing up, both for the medium and the characters, Tetsuo's tragic failure is his arrested development. He resents his gangmates for treating him like the little brother. Faced with the limitless possibilities his powers open for him, all he can do is mindlessly consume and destroy without any distinction between enemies and followers. In other words, his behavior isn't so much a righteous judgment as the random chaos of a toddler pitching a fit. Kaneda even spells it out: "I figured you'd be standing here crying like a little baby."

And that's eventually what Tetsuo becomes, minus the "little" part. When he loses control of his power, he at first seems to be evolving into his superhuman ideal, with his muscles swelling grotesquely while his head stays the same size. But when we see him looming behind his girlfriend Kaori, he's grown into an enormous infant, puking and crying everywhere. "Power doesn't corrupt," says historian Robert Caro, "it reveals" (via Goodreads). In this case, he couldn't be more right.

The climax turns the 1964 Tokyo Olympics on its head

Tetsuo finds Akira's remains hidden underneath the stadium for the upcoming 2020 Olympic ceremony, and sets up the venue as his throne room. In the end, he destroys Neo-Tokyo just as Akira had destroyed the original city.

Andrew Osmond points out the historical resonance of this sequence in "100 Animated Feature Films." In real life, Allied firebombing destroyed Tokyo during World War II. But as Ian Buruma details in "Inventing Japan, 1853–1964," the "economic miracle" of the Marshall Plan had rebuilt Japan into a major world power again. In 1952, the Allied occupation had ended, and in 1964, Japan announced its return to the world stage by hosting the Olympics. It was a symbol of victory after the nation's crushing defeat, something the Olympic Committee made explicit by choosing a Hiroshima survivor to carry the torch.

But, there was no guarantee that the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki would be a one-off in 1988, and in the age of nuclear anxiety, Otomo recognized how fragile Japan's resurgence was. Maybe that's why Akira's first destruction of Tokyo takes place not in the future, but in the present. It's not a stretch to assume Neo-Tokyo wanted the 2020 Olympics to announce its return from the brink just as the 1964 Olympics did — and it all literally blows up in their faces.