Indie Films You Didn't Know Were Made By Famous Directors

In the dark corners of many great directors' filmographies, there are outliers. Small films that got made before or between big ones, experiments released to miniscule audiences, or even films that weren't intended to be released at all.

These works are often ignored in favor of the more acclaimed, well-known efforts by their filmmakers, but these black sheep nonetheless have tremendous value. They provide a deeper sense of who these directors are, seeing what they create when working without the confines of a studio, and revealing what stories and ideas are truly closest to their hearts. If they could simply make films — and not make a living — perhaps this is what their filmography would more closely resemble.

The movies below are among their most obscure, some that were designed to be adumbrated by their brethren, others gems waiting to be discovered. But all of them are worth knowing, completing the pictures of these filmmakers — even if it sometimes means exposing their greatest weaknesses.

Jonathan Demme, Storefront Hitchcock

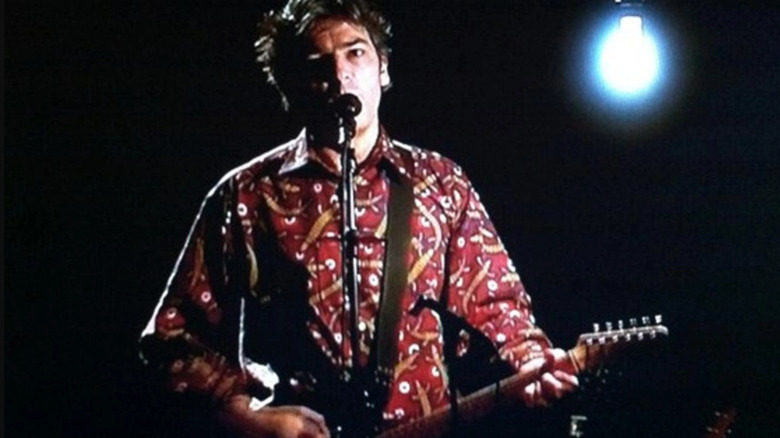

As he was directing high-profile studio efforts like "The Silence of the Lambs" and "Philadelphia," Jonathan Demme still maintained a side career as a documentarian, filming activists and musicians alike. His most famous documentary is the Talking Heads concert movie "Stop Making Sense," but he made an equally good, if far more obscure performance film in 1998 with "Storefront Hitchcock," about British singer-songwriter Robyn Hitchcock.

Rather than the elaborate production of "Stop Making Sense," Demme maintained a minimalist approach for "Storefront," having Hitchcock perform in a bare storefront with the only visible audience being the uncaring people passing by the window. Hitchcock doesn't need any on-stage distractions; he's compelling enough just playing his gorgeous music and spinning surreal, funny monologues between the songs.

Demme somehow never runs out of interesting ways to film a single man with a guitar, and what little bits of set dressing he does include — such as a bare lightbulb and a traffic cone — do a lot to emphasize Hitchcock's eccentric, sweet worldview. By the end, Demme and Hitchcock have made solitude seem like a profound thing to experience, an opportunity for creativity and joy, even with the sadness that sometimes takes over.

Francis Ford Coppola, Youth Without Youth, Tetro, and Twixt

Francis Ford Coppola's career will always be defined primarily by his work in the '70s, but there are interesting, experimental efforts spread across every decade he's made movies. perhaps the most interesting, if not the best, work of his career is the trilogy of low-budget experiments he made from 2007 to 2011, "Youth Without Youth," "Tetro," and "Twixt."

Working completely outside the studio system, Coppola was free to take chances on all three movies, making odder and more overtly personal movies than he'd ever done before. The only thing connecting the three is Coppola's use of the then-new digital filmmaking technology, which allowed him to create images as beautiful and artificial as the ones he had created with analog means on "Bram Stoker's Dracula" and "One From the Heart." The surreal visual atmosphere befits all three films, particularly the dense "Youth Without Youth" story of manipulating time and discovering the secrets of humanity in the process. "Twixt" goes to similarly bizarre places, telling a murder mystery involving the ghost of Edgar Allan Poe that was partly adapted from Coppola's actual nightmares, but also allowing for digressions like Val Kilmer doing multiple celebrity impressions in his hotel room. "Tetro" is the most conventional of the three but also the most powerful, using Coppola's heightened style to sell the melodrama of a family where the sons have been pitted against their father. Decades after "The Godfather," Coppola still wields a gift for depicting powerful family tragedies.

Martin Scorsese, Boxcar Bertha

Demme, Coppola, and several other beloved directors all began their careers under the tutelage of producer Roger Corman, making exploitation movies as fast and cheap as possible. One of Corman's most distinguished alumni is Martin Scorsese, who followed his 1967 debut "Who's That Knocking At My Door" with the Corman-produced crime movie "Boxcar Bertha."

"Bertha" is most famous for inspiring director John Cassavetes to tell Scorsese he had wasted his time making it, saying "it's a good picture, but you're better than the kind of people who make this kind of movie." After that intervention, Scorsese made the more personal "Mean Streets," launching the prestigious career he continues to this day.

But "Bertha" does have its merits, allowing Scorsese to make one of the gangster b-movies he loved as a child without the lofty aspirations of his subsequent crime movies. It's also a rare opportunity to see a Scorsese crime movie led by a woman, in this case Barbara Hershey as an impoverished young woman who joins David Carradine's union organizer in a series of railway robberies. Their adventures are entertaining except when they turn violent, which is when Scorsese's future talent for artful brutality comes into focus.

Noah Baumbach, Highball

Noah Baumbach's "Highball" is the least known film in Baumbach's filmography, and that's how Baumbach would like it to stay.

Shot in a week with much of the same cast and crew of Baumbach's second film "Mr. Jealousy," "Highball" tells the loose story of a couple holding three disastrous parties in their apartment. Baumbach later said he didn't give himself enough time to properly finish shooting and editing "Highball," and after he abandoned it, it was released on DVD without his consent and with pseudonyms replacing him as writer and director.

Baumbach is correct in believing that the 1997 release was unfinished, hamstrung by awkward editing and a general lack of care given to the visuals. It was marketed with a poster that made it look like a wannabe "Swingers." But this lack of polish ceases to matter when the end result is one of the funniest movies Baumbach has ever made. It's a great showcase for Baumbach's early collaborators, gifted comedic actors like Chris Eigeman, Eric Stoltz, and Carlos Jacott, who Baumbach largely stopped working with after this movie.

Whether or not Baumbach could've done a better job filming the script, what makes it on-screen is hilarious, filled with sharp dialogue and wonderful comic setpieces about low-rent magicians and dueling lizard Halloween costumes. The technical faults only occasionally intrude on the consistent hilarity, and the abbreviated 79-minute runtime ensures it never overstays its welcome.

Greta Gerwig, Nights and Weekends

Greta Gerwig's beginnings were in the mid-2000s movement of independent comedies dubbed "mumblecore," known for their unpolished visuals, often improvised conversations, and stories about the relationships and responsibilities of twentysomethings. Gerwig's most frequent collaborator in the mumblecore days was director Joe Swanberg, first breaking through as the title character in Swanberg's "Hannah Takes the Stairs." Gerwig's final film with Swanberg, "Nights and Weekends," also marks her directorial debut, co-directing and starring with Swanberg almost a decade before her first solo directing credit on "Lady Bird."

2008's "Nights and Weekends" can't compare to the subsequent films Gerwig directed or wrote with Noah Baumbach. Gerwig's strength as a filmmaker is her witty, precisely worded dialogue, which doesn't often come across in a genre known for improvisation above scripts and makes this slightly shapeless next to the tight structure of "Lady Bird" or "Frances Ha." But the film's story, of a long-distance relationship that goes sour, is powerful enough to overcome its problems.

The film's story developed as Gerwig and Swanberg's real-life relationship began to collapse, and it has the uncomfortable intimacy of watching an actual couple deal with problems they can't fix. Gerwig, usually a vibrant actor above all else, seems tired and beaten down by the end of this, knowing that she can't hold onto her partner for much longer.

M. Night Shyamalan, Praying with Anger and Wide Awake

M. Night Shyamalan seemingly came out of nowhere with "The Sixth Sense," experiencing blockbuster success and acclaim on most people's first exposure to him. But "Sense" was not in fact his debut; he had made two little-seen movies in the years before it, 1992's "Praying with Anger" and 1998's "Wide Awake." They have a lot in common with each other, and not much in common with any other Shyamalan movies, perhaps presenting an alternate timeline version of a Shyamalan who never made a horror movie.

"Praying" and "Awake" are both coming-of-age stories, following young men struggling to make sense of their lives in the wake of family tragedies. Shyamalan himself plays the young man at the center of "Praying," and while he'd later be the butt of some jokes for appearing in his movies, he's a decent enough lead, whose only problem is that he has to read his own ham-fisted dialogue. "Praying" is almost entirely long-winded speeches, scene after scene of characters explaining themselves rather than actually doing anything.

Shyamalan apparently hadn't grown much as a writer when he made "Wide Awake," still believing characters have to show their feelings by explaining them at length. "Awake" is even worse than "Praying" because it's also a silly kids movie, with dumb gags sitting uneasily between the expressions of grief. One of the only things the film had going for it at the time of release was that co-star Rosie O'Donnell had recently launched her daytime talk show, becoming something of a hot commodity at the time. Nevertheless, the film's bland hijinks and lack of visual imagination would completely distance it from Shyamalan's future work, if it didn't have Shyamalan's first and least impactful twist ending.

Paul Verhoeven, Tricked

After an impressive Hollywood blockbuster run that included "Starship Troopers" and "RoboCop," Paul Verhoeven returned to his native Netherlands after the artistic disappointment of "Hollow Man." There, he made the acclaimed romantic war epic "Black Book," as well as the odd experiment "Tricked." The story of how "Tricked" got made is more interesting than the story it tells, however, a notable element in what's otherwise the most forgettable project of Verhoeven's career.

"Tricked" began as a single scene directed by Verhoeven, after which internet users were asked to write scripts completing the story in their own ways. Verhoeven then pieced together several of those user-generated scripts to create the final version of 2012's "Tricked," a 55-minute feature.

The process of making "Tricked" doesn't show on-screen, as events follow seamlessly from each other with no evidence that it's made up of so many different pieces. In this way, "Tricked" is a success, but the end result isn't a creative success. It's a familiar sex comedy, following a rich family through a series of affairs and business schemes that threaten to destroy them. There are some laughs, but mostly this lacks Verhoeven's typical biting wit, tackling boardroom and romantic drama in predictable ways more fitting for sitcom than satire. Verhoeven would soon rebound with the Oscar-nominated "Elle," making "Tricked" no more than an odd detour in his career.

Steven Soderbergh, Schizopolis

Steven Soderbergh has made a career of alternating between big Hollywood projects and uncommercial independent films, following "Ocean's" movies with low-budget digital experiments and Che Guevara biopics. Nothing in his vast filmography is quite as uncommercial, however, as 1996's "Schizopolis," the anarchic comedy that's also a reflection of Soderbergh's failed first marriage.

Soderbergh directed, wrote, and served as his own cinematographer on "Schizopolis," as he would on many of his bigger-budget movies. But for the first and only time, Soderbergh also acted, playing the movie's two lead roles of a speechwriter for a Scientology stand-in and a dentist having an affair with the speechwriter's wife. On this evidence, Soderbergh could've made a career of acting, as he's full of great deadpan reactions to the silliness he's surrounded himself with. He also sells what becomes the emotional undertow of "Schizopolis," the failure of communication within a marriage.

Soderbergh's wife in "Schizopolis" is played by his real-life ex Betsy Brantley, and their scenes together, even the funny ones, sell the crushing burden of not being able to connect to the person closest to you. Soderbergh would never allow himself to get this personal in a movie again, making "Schizopolis" a rare, fascinating document of the man behind some of the biggest and most beloved movies of recent times, in addition to a masterful comedy.

Kathryn Bigelow, The Loveless

Kathryn Bigelow's most acclaimed films, particularly "The Hurt Locker" and "Point Break," view masculinity from an outside perspective, finding both sweetness and frightening violence within these men. This theme began all the way back in Bigelow's directorial debut, the moody crime drama "The Loveless." The 1981 drama was itself a promising enough debut, but Bigelow would find much greater insight on the male psyche in her later work.

In addition to being Bigelow's debut, "The Loveless" is also one of the first major screen roles for Willem Dafoe, playing a member of a motorcycle gang who rides into a small town and falls in love with the daughter of an anti-biker zealot. Dafoe's considerable charisma is already in place and he's the main reason to watch this film, despite its many faults.

There's a compelling idea about Dafoe's lover getting caught between two opposing but similarly toxic brands of masculinity, but it's not dwelled upon enough between endless scenes of tough-guy slang and brooding. "The Loveless" only runs 85 minutes, but it still drags on and on, with not much of note happening until the gut-punch ending. Bigelow's next film was "Near Dark," which would replace the bikers with vampires and make every compelling idea in "The Loveless" part of a scarier, exciting whole, rather than a concept more interesting to think about than watch.

Tony Scott, Loving Memory

From his start in Hollywood to his death in 2012, Tony Scott almost exclusively made big-budget action thrillers. But as he went on, those thrillers became defined by their experimentation as much as their action, using avant-garde visual and editing techniques as new ways of creating blockbuster thrills. Scott's late turn towards arthouse conventions may be unexpected from the director of "Top Gun," but it makes sense after watching his debut, a strange 50-minute feature called "Loving Memory."

The 1971 film shows Scott's artistic side without any of the action movie conventions, following two elderly siblings after they kill a bicyclist, take him home with them, and pretend that he's their dead brother. Scott's style is slow-moving black-and-white shots, interrupted by jarringly loud noises made by even the most ordinary household items. Scott creates a masterfully unsettling atmosphere, keeping the audience as off-balance as he did in his later Hollywood work.

"Loving Memory" is ultimately not as good as that later work because of Scott's efforts as a screenwriter, a position he never took again on any of his movies. This was for the best, as Scott's script relies too heavily on monologues that detail the siblings' delusions when the premise itself is more than enough to get those delusions across. Scott would soon learn that visuals could be a far more important tool to convey his messages than words.

Spike Lee, Red Hook Summer and Da Sweet Blood of Jesus

2018's "BlacKkKlansman" and 2020's "Da 5 Bloods" was seen as a comeback for Spike Lee, who had spent the prior decade mostly making critical and commercial bombs for increasingly smaller audiences. The audiences became particularly miniscule for two Lee films in this period, 2012's "Red Hook Summer" and 2014's "Da Sweet Blood of Jesus."

"Red Hook" and "Sweet Blood" don't share much in common. "Red Hook" is a slice of life about the Red Hook Projects in Brooklyn, while "Sweet Blood" is Lee's remake of the cult-classic Black vampire movie "Ganja & Hess." But they share Lee's desire to separate from Hollywood in this period, making the movies he wants to make without any of the concessions that come with studio work.

"Red Hook" was made on a shoestring budget, with much of its crew being Lee's students from when he taught film at NYU, and "Sweet Blood" was financed entirely through Kickstarter. Lee spoke out against the Hollywood system during this period, complaining that the studios refused to greenlight anything besides safe, guaranteed tentpoles. Lee certainly doesn't play it safe in either movie, taking serious risks like inserting a last-minute subplot about abusive Catholic priests into "Red Hook." His risk-taking, even in the face of potential embarrassment, is one of Lee's defining features as a filmmaker, and while the risks in these two didn't pay off, their failings showed a director still courageous enough to put himself out on a limb.

Richard Linklater, SubUrbia and Tape

Richard Linklater loves to make movies that focus on people talking to each other, which makes him an ideal fit to direct an adaptation of a play. He's made two theatrical adaptations in his career, 1996's "SubUrbia" and 2001's "Tape," which are both among his lesser-known works and are distinguished from the rest of Linklater's filmography by their vicious cynicism.

"SubUrbia" has a familiar template for a Linklater movie, watching a group of aimless twentysomethings wander around their hometown and talk. It fits right in with "Dazed and Confused" or "Everybody Wants Some!!" even if it is based on an Eric Bogosian play. But Linklater protagonists are usually talking about their dreams and aspirations, while all the characters in "SubUrbia" want to do is haunt convenience store parking lots and delay their entry into adulthood. These are miserable, unpleasant kids, and there's no sense that there's anything better waiting for them in the future. The film puts young Giovanni Ribisi and Steve Zahn alongside Linklater faves like Nicky Katt and Parker Posey.

Ethan Hawke's character in "Tape" has reached a similar dead-end to the "SubUrbia" kids, and he wants to drag his former best friend (played by Robert Sean Leonard) down with him. He gets Leonard to confess a dark secret from their college days, then blackmails him with the information, for no other reason than jealousy over Leonard being much more successful than he is. Co-starring Uma Thurman, "Tape" is not an easy movie to watch, its grimy early digital video aesthetic making the ugly subject matter even harder to take, but it's worthwhile if only for the Hawke performance — a fearless portrayal of manic self-loathing and cynicism.

Denis Villeneuve, Enemy

Denis Villeneuve has emerged as a top blockbuster director in recent years with the success of "Dune," a surprising turn for a director whose work is more often alienating and grim than crowd-pleasing. This is especially true of the movies Villeneuve made in his native Canada, including his final Canadian film to date, 2013's "Enemy." Made after his first American film "Prisoners," and sharing its lead actor Jake Gyllenhaal, "Enemy" might be the most impenetrable movie of Villeneuve's career, creating an atmosphere of indescribable doom.

"Enemy" takes place in a nightmare version of Toronto, a gross yellow-tinted place where Gyllenhaal's professor discovers a man who looks exactly like him, also played by Gyllenhaal. The professor is defined by his shyness and repression, while his double lives the outgoing life that the professor wishes he could have. Aside from the recurring image of giant spiders, looking ahead to the similarly bizarre giant creatures in "Arrival" and "Dune," the action in "Enemy" is almost all internal rather than external, a battle between dueling sides of one man's personality that may not produce a good outcome no matter which side wins out. "Enemy" is a challenging watch but a fascinating one, with an ending hard to understand, but even harder to forget.

Alfonso Cuarón, Sólo con tu pareja

Alfonso Cuarón's career began for many with the release of "Y tu mama tambien" in 2001, but he had already made advances as a Hollywood director twice beforehand, winning some acclaim for "A Little Princess" and "Great Expectations" but not enough. His debut, the Spanish-language sex comedy "Sólo con tu pareja," is even lesser-regarded, not getting an American release of any kind until 2006.

"Sólo con tu pareja" is far from Cuarón's best, a disposable farce where a serial womanizer is brought down to earth when he's given a false blood test saying he has AIDS. Cuarón mostly avoids the potential bad taste of the premise, but he doesn't get that many laughs in the process, staging comedic setpieces that are more wacky than funny. Cuarón does a much better job turning sex into laughs in "Y tu mama," which also has a sneaky poignancy this doesn't bother to include.

The most impressive work in "pareja" is done by Cuarón's most loyal collaborator, cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, who makes the apartment setting of much of the film look alternately lush and foreboding. It's far from the naturally-lit handheld photography Lubezki made his name for in the 2000s; overall, the film may be more revealing of the future successes of Lubezki than Cuarón.